On Report of the Respective Committees, the Following Were Ordered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomie in Theorie Und Praxis 8. Auflage in Zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski

Astronomie in Theorie und Praxis 8. Auflage in zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Beobachtungen mit bloßem Auge 37 Motivation 37 Hilfsmittel 38 Drehbare Sternkarte Bücher und Atlanten Kataloge Planetariumssoftware Elektronischer Almanach Sternkarten 39 2 Atmosphäre der Erde 49 Aufbau 49 Atmosphärische Fenster 51 Warum der Himmel blau ist? 52 Extinktion 52 Extinktionsgleichung Photometrie Refraktion 55 Szintillationsrauschen 56 Angaben zur Beobachtung 57 Durchsicht Himmelshelligkeit Luftunruhe Beispiel einer Notiz Taupunkt 59 Solar-terrestrische Beziehungen 60 Klassifizierung der Flares Korrelation zur Fleckenrelativzahl Luftleuchten 62 Polarlichter 63 Nachtleuchtende Wolken 64 Haloerscheinungen 67 Formen Häufigkeit Beobachtung Photographie Grüner Strahl 69 Zodiakallicht 71 Dämmerung 72 Definition Purpurlicht Gegendämmerung Venusgürtel Erdschattenbogen 3 Optische Teleskope 75 Fernrohrtypen 76 Refraktoren Reflektoren Fokus Optische Fehler 82 Farbfehler Kugelgestaltsfehler Bildfeldwölbung Koma Astigmatismus Verzeichnung Bildverzerrungen Helligkeitsinhomogenität Objektive 86 Linsenobjektive Spiegelobjektive Vergütung Optische Qualitätsprüfung RC-Wert RGB-Chromasietest Okulare 97 Zusatzoptiken 100 Barlow-Linse Shapley-Linse Flattener Spezialokulare Spektroskopie Herschel-Prisma Fabry-Pérot-Interferometer Vergrößerung 103 Welche Vergrößerung ist die Beste? Blickfeld 105 Lichtstärke 106 Kontrast Dämmerungszahl Auflösungsvermögen 108 Strehl-Zahl Luftunruhe (Seeing) 112 Tubusseeing Kuppelseeing Gebäudeseeing Montierungen 113 Nachführfehler -

Meeting Abstracts

228th AAS San Diego, CA – June, 2016 Meeting Abstracts Session Table of Contents 100 – Welcome Address by AAS President Photoionized Plasmas, Tim Kallman (NASA 301 – The Polarization of the Cosmic Meg Urry GSFC) Microwave Background: Current Status and 101 – Kavli Foundation Lecture: Observation 201 – Extrasolar Planets: Atmospheres Future Prospects of Gravitational Waves, Gabriela Gonzalez 202 – Evolution of Galaxies 302 – Bridging Laboratory & Astrophysics: (LIGO) 203 – Bridging Laboratory & Astrophysics: Atomic Physics in X-rays 102 – The NASA K2 Mission Molecules in the mm II 303 – The Limits of Scientific Cosmology: 103 – Galaxies Big and Small 204 – The Limits of Scientific Cosmology: Town Hall 104 – Bridging Laboratory & Astrophysics: Setting the Stage 304 – Star Formation in a Range of Dust & Ices in the mm and X-rays 205 – Small Telescope Research Environments 105 – College Astronomy Education: Communities of Practice: Research Areas 305 – Plenary Talk: From the First Stars and Research, Resources, and Getting Involved Suitable for Small Telescopes Galaxies to the Epoch of Reionization: 20 106 – Small Telescope Research 206 – Plenary Talk: APOGEE: The New View Years of Computational Progress, Michael Communities of Practice: Pro-Am of the Milky Way -- Large Scale Galactic Norman (UC San Diego) Communities of Practice Structure, Jo Bovy (University of Toronto) 308 – Star Formation, Associations, and 107 – Plenary Talk: From Space Archeology 208 – Classification and Properties of Young Stellar Objects in the Milky Way to Serving -

第 28 届国际天文学联合会大会 Programme Book

IAU XXVIII GENERAL ASSEMBLY 20-31 AUGUST, 2012 第 28 届国际天文学联合会大会 PROGRAMME BOOK 1 Table of Contents Welcome to IAU Beijing General Assembly XXVIII ........................... 4 Welcome to Beijing, welcome to China! ................................................ 6 1.IAU EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE, HOST ORGANISATIONS, PARTNERS, SPONSORS AND EXHIBITORS ................................ 8 1.1. IAU EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ..................................................................8 1.2. IAU SECRETARIAT .........................................................................................8 1.3. HOST ORGANISATIONS ................................................................................8 1.4. NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE ........................................................9 1.5. NATIONAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE ..................................................9 1.6. LOCAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE .......................................................10 1.7. ORGANISATION SUPPORT ........................................................................ 11 1.8. PARTNERS, SPONSORS AND EXHIBITORS ........................................... 11 2.IAU XXVIII GENERAL ASSEMBLY INFORMATION ............... 14 2.1. LOCAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE OFFICE .......................................14 2.2. IAU SECRETARIAT .......................................................................................14 2.3. REGISTRATION DESK – OPENING HOURS ...........................................14 2.4. ON SITE REGISTRATION FEES AND PAYMENTS ................................14 -

Meteor Activity Outlook for May 8-14, 2021

Meteor Activity Outlook for May 8-14, 2021 David Alger used a Sony A7sII 4K video camera and a Samyang 12mm f2.8 lens to capture this fireball on March 23, 2021, from Portsmouth, England, GB. Notice that is passes just above the stars of the "Big Dipper" (Ursa Major) . ©David Alger During this period the moon reaches its new phase on Tuesday May 11th. On this date the moon is located near the sun and is invisible at night. This weekend the waning crescent moon will rise during the early morning hours but will not interfere with meteor observing as it will be too thin and only in the sky an hour or two prior to sunrise. The estimated total hourly meteor rates for evening observers this week is near 3 as seen from mid-northern latitudes (45N) and 4 as seen from tropical southern locations (25S). For morning observers, the estimated total hourly rates should be near 11 as seen from mid-northern latitudes (45N) and 23 as seen from tropical southern locations (25S). The actual rates will also depend on factors such as personal light and motion perception, local weather conditions, alertness, and experience in watching meteor activity. Note that the hourly rates listed below are estimates as viewed from dark sky sites away from urban light sources. Observers viewing from urban areas will see less activity as only the brighter meteors will be visible from such locations. The radiant (the area of the sky where meteors appear to shoot from) positions and rates listed below are exact for Saturday night/Sunday morning May 8/9. -

Stars, Galaxies, and Beyond, 2012

Stars, Galaxies, and Beyond Summary of notes and materials related to University of Washington astronomy courses: ASTR 322 The Contents of Our Galaxy (Winter 2012, Professor Paula Szkody=PXS) & ASTR 323 Extragalactic Astronomy And Cosmology (Spring 2012, Professor Željko Ivezić=ZXI). Summary by Michael C. McGoodwin=MCM. Content last updated 6/29/2012 Rotated image of the Whirlpool Galaxy M51 (NGC 5194)1 from Hubble Space Telescope HST, with Companion Galaxy NGC 5195 (upper left), located in constellation Canes Venatici, January 2005. Galaxy is at 9.6 Megaparsec (Mpc)= 31.3x106 ly, width 9.6 arcmin, area ~27 square kiloparsecs (kpc2) 1 NGC = New General Catalog, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_General_Catalogue 2 http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2005/12/image/a/ Page 1 of 249 Astrophysics_ASTR322_323_MCM_2012.docx 29 Jun 2012 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Useful Symbols, Abbreviations and Web Links .................................................................................................................. 4 Basic Physical Quantities for the Sun and the Earth ........................................................................................................ 6 Basic Astronomical Terms, Concepts, and Tools (Chapter 1) ............................................................................................. 9 Distance Measures ...................................................................................................................................................... -

O Personenregister

O Personenregister A alle Zeichnungen von Sylvia Gerlach Abbe, Ernst (1840 – 1904) 100, 109 Ahnert, Paul Oswald (1897 – 1989) 624, 808 Airy, George Biddell (1801 – 1892) 1587 Aitken, Robert Grant (1864 – 1951) 1245, 1578 Alfvén, Hannes Olof Gösta (1908 – 1995) 716 Allen, James Alfred Van (1914 – 2006) 69, 714 Altenhoff, Wilhelm J. 421 Anderson, G. 1578 Antoniadi, Eugène Michel (1870 – 1944) 62 Antoniadis, John 1118 Aravamudan, S. 1578 Arend, Sylvain Julien Victor (1902 – 1992) 887 Argelander, Friedrich Wilhelm August (1799 – 1875) 1534, 1575 Aristarch von Samos (um −310 bis −230) 627, 951, 1536 Aristoteles (−383 bis −321) 1536 Augustus, Kaiser (−62 bis 14) 667 Abbildung O.1 Austin, Rodney R. D. 907 Friedrich W. Argelander B Baade, Wilhelm Heinrich Walter (1893 – 1960) 632, 994, 1001, 1535 Babcock, Horace Welcome (1912 – 2003) 395 Bahtinov, Pavel 186 Baier, G. 408 Baillaud, René (1885 – 1977) 1578 Ballauer, Jay R. (*1968) 1613 Ball, Sir Robert Stawell (1840 – 1913) 1578 Balmer, Johann Jokob (1825 – 1898) 701 Abbildung O.2 Bappu, Manali Kallat Vainu (1927 – 1982) 635 Aristoteles Barlow, Peter (1776 – 1862) 112, 114, 1538 Bartels, Julius (1899 – 1964) 715 Bath, KarlLudwig 104 Bayer, Johann (1572 – 1625) 1575 Becker, Wilhelm (1907 – 1996) 606 Bekenstein, Jacob David (*1947) 679, 1421 Belopolski, Aristarch Apollonowitsch (1854 – 1934) 1534 Benzenberg, Johann Friedrich (1777 – 1846) 910, 1536 Bergh, Sidney van den (*1929) 1166, 1576, 1578 Bertone, Gianfranco 1423 Bessel, Friedrich Wilhelm (1784 – 1846) 628, 630, 1534 Bethe, Hans Albrecht (1906 – 2005) 994, 1010, 1535 Binnewies, Stefan (*1960) 1613 Blandford, Roger David (*1949) 723, 727 Blazhko, Sergei Nikolajewitsch (1870 – 1956) 1293 Blome, HansJoachim 1523 Bobrovnikoff, Nicholas T. -

X Cygni, September 2002 Variable Star of the Month Variable Star of the Month

AAVSO: X Cygni, September 2002 Variable Star Of The Month Variable Star Of The Month September, 2002: X Cygni Amateur Astronomer Discovers the Cepheid X Cygni and Much More! The Cepheid, X Cygni, was first noted for its variable behavior in 1886 by the American amateur astronomer Seth C. Chandler, Jr. Chandler, a resident of Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, had been independently monitoring the changing beacons of light in the earliest days of variable star astronomy. In fact, Chandler was observing variables 35 years before the formation of the AAVSO. Although he received no formal college training, Chandler had a natural talent for mathematics and by today's standards, was considered a human computer. In the years 1881 through 1885, Chandler worked as a volunteer observer and researcher at the Harvard College Observatory furthering his knowledge and enriching the field with his findings. Chandler was a great friend to the cause of variable star observing and encouraged others to do the same by publishing a series of articles on how to observe variable stars. Although he clearly displayed a talent for the science, Chandler opted to remain an independent amateur astronomer and continued to work his "day job" as an actuary for an insurance company. X Cygni's discovery was announced by Chandler in the Astronomical The Cepheid variable X Journal in 1886. From his first calculations, he found the star to have a Cygni and its discoverer, magnitude range of 6.3 to 7.6 and a period of just over 14 days Seth C. Chandler, Jr. (1846-1913). (Chandler 1886a), which he modified later that year to 15.6 days noting the duration of increase to be 5.6 days and that of decrease to be 10 days (Chandler 1886b). -

Spectral Line Shapes in Plasmas

Spectral Line Shapes in Plasmas Edited by Evgeny Stambulchik, Annette Calisti, Hyun-Kyung Chung and Manuel Á. González Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Atoms www.mdpi.com/journal/atoms Evgeny Stambulchik, Annette Calisti, Hyun-Kyung Chung and Manuel Á. González (Eds.) Spectral Line Shapes in Plasmas This book is a reprint of the special issue that appeared in the online open access journal Atoms (ISSN 2218-2004) in 2014 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/atoms/special_issues/SpectralLineShapes). Guest Editors Evgeny Stambulchik Hyun-Kyung Chung Department of Particle Physics International Atomic Energy Agency, Atomic and and Astrophysics, Molecular Data Unit, Nuclear Data Section, P.O. Faculty of Physics, Box 100, A-1400 Vienna, Austria Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel Annette Calisti Manuel Á. González Laboratoire PIIM, UMR7345, Departamento de Física Aplicada, Escuela Técnica Aix-Marseille Université - CNRS, Superior de Ingeniería Informática, Centre Saint Jérôme case 232, Universidad de Valladolid, Paseo de Belén 15, 13397 Marseille Cedex 20, France 47011 Valladolid, Spain Editorial Office Publisher Production Editor MDPI AG Shu-Kun Lin Martyn Rittman Klybeckstrasse 64 4057 Basel, Switzerland 1. Edition 2015 MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan ISBN 978-3-906980-82-9 © 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI AG, Basel, Switzerland. All articles in this volume are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited. The dissemination and distribution of copies of this book as a whole, however, is restricted to MDPI AG, Basel, Switzerland. -

Sky Notes by Neil Bone 2004 June & July

Sky notes by Neil Bone 2004 June & July and no-one alive today has ever seen one. Transits of Venus occur in pairs separated Sun, Moon and Earth The 2004 transit will be intensively covered by 8 years: the second in the series is in 2012, by those wishing to photograph and image and only the closing stages and egress will be The Sun reaches its greatest northerly decli- it, as well as by visual observers keen to visible from the British Isles on that occasion. nation for the year at 00h 57m Universal Time witness a rare astronomical spectacle. After 2012, there is a long wait until 2117. (UT=GMT; BST minus 1 hour) on June 21, The usual cautionary note with respect to the northern hemisphere Summer Solstice. solar observing applies to the transit. Projec- The hours of daylight are at a maximum for a tion is the safest way to view the event. Objec- week or so to either side of this date, and with tive filters can be used, but only if the observer the Sun never very far below the horizon even is absolutely sure, via the manufacturer’s speci- The planets at midnight, the short midsummer nights never fications and instructions, that these are safe. really become properly dark at the latitudes Advice on safe observing, along with other as- of the British Isles. Particularly in Scotland, pects of the transit, can be found on the website Mercury is at superior conjunction on the Northern Ireland and the Northern Isles, the at http://www.transitofvenus2004.org.uk/ far side of the Sun on June 18, then emerges nights are brief and twilit. -

Cycle 10 Abstract Catalog (Based on Phase I Submissions)

Cycle 10 Abstract catalog (based on Phase I submissions) ================================================================================ Proposal Category: GO Scientific Category: Cosmology ID: 9033 Title: Measuring the mass distribution in the most distant, very X-ray luminous galaxy cluster known PI: Harald Ebeling PI Institution: Institute for Astronomy We propose to obtain a mosaic of deep HST/WFPC2 images to conduct a weak lensing analysis of the mass distribution in the massive, distant galaxy cluster ClJ1226.9+3332, recently discovered by us. At z=0.888 this exceptional system is more X-ray luminous and more distant than both MS1054.4-0321 and ClJ0152.7-1357, the previous record holders, thus providing yet greater leverage for cosmological studies of cluster evolution. ClJ1226.9+3332 differs markedly from all other currently known distant clusters in that it exhibits little substructure and may even host a cooling flow, suggesting that it could be the first cluster to be discovered at high redshift that is virialized. We propose joint HST and Chandra observations to investigate the dynamical state of this extreme object. This project will 1) take advantage of HST's superb resolution at optical wavelengths to accurately map the mass distribution within 1.9 h^-1_ 50 Mpc via strong and weak gravitational lensing, and 2) use Chandra's unprecedented resolution in the X-ray waveband to obtain independent constraints on the gas and dark matter distribution in the cluster core, including the suspected cooling flow region. As a bonus, the proposed WFPC2 observations will allow us to test the results by van Dokkum et al. (1998, 1999) on the properties of cluster galaxies (specifically merger rate and morphologies) at z~ 0.8 from their HST study of MS1054.4-0321. -

STARHOPP in LYRA

STARHOPP in LYRA von Andreas Schnabel Milchstraßenpanorama mit den Sternbildern Cygnus und Lyra 1. Mythologischer Hintergrund: Ein kleines, aber auffälliges Sternbild, das von Wega geschmückt wird, dem fünfthellsten Stern am Himmel. Mythologisch war die Leier das Instrument des großen Musikers Orpheus, dessen Gang in die Unterwelt eine der berühmtesten griechischen Geschichten überhaupt ist. Dies ist die erste Leier, die jemals gefertigt wurde, eine Erfindung des Hermes, des Sohnes des Zeus und der Maia, einer der Plejaden. Hermes fertigte die Leier aus dem Panzer einer Schildkröte, die vor seiner Höhle auf dem Berg Kyllene in Arkadien herumkroch. Hermes reinigte den Panzer, durchbohrte den Rand und zog sieben Schafsdärme hindurch, ebenso viele wie es Plejaden gab. Zugleich erfand er das Plektron, mit dem man das Instrument spielt. Diese Leier half Hermes nach einem Bubenstreich aus der Klemme, denn er hatte Vieh gestohlen, das dem Apollon gehörte. Apollon forderte erzürnt seine Rückgabe, doch als er den schönen Klang der Leier hörte, ließ er dem Hermes das Vieh und nahm im Tausch dafür die Leier.RATOSTHENES E sagt, dass Apollon später Orpheus die Leier übergab, der auf ihr seine Lieder begleitete. Orpheus war der größte Musiker der alten Zeit, der mit seinen. Liedern sogar Felsen und Flüsse bezaubern konnte. Er soll mit dem Klang seiner Leier auch Reihen von Eichen an die Küste Thrakiens gelockt haben. Orpheus schloss sich der Expedition Jasons und der Argonauten an, die sich aufgemacht hatten, das Goldene Vlies zu holen. Als die Argonauten den verführerischen Gesang der Sirenen hörten • Meernymphen, die Generationen von Seeleuten ins Verderben gelockt hatten, übertönte Orpheus ihren Gesang mit seinen eigenen Liedern. -

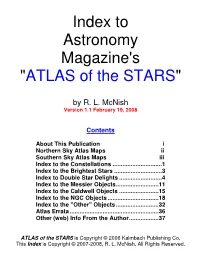

ATLAS of the STARS "

Index to Astronomy Magazine's "ATLAS of the STARS " by R. L. McNish Version 1.1 February 19, 2008 Contents About This Publication i Northern Sky Atlas Maps ii Southern Sky Atlas Maps iii Index to the Constellations ..............................1 Index to the Brightest Stars .............................3 Index to Double Star Delights ..........................4 Index to the Messier Objects..........................11 Index to the Caldwell Objects ........................15 Index to the NGC Objects ...............................18 Index to the "Other" Objects ..........................32 Atlas Errata ......................................................36 Other (web) Info From the Author..................37 ATLAS of the STARS is Copyright © 2006 Kalmbach Publishing Co. This Index is Copyright © 2007-2008, R. L. McNish, All Rights Reserved. About This Publication This Index to Astronomy Magazine's Atlas of the Stars was created to augment the Atlas which was published by Kalmbach Publishing Co. This Index was independently created by close examination of every object identified on all 24 double page maps in the Atlas then combining all the results into the 7 complete indices. Additionally, the author created the diagrams on the next 2 pages to show the overlapping relationships of all the Atlas maps in the Northern and Southern hemispheres of the sky. A page of "Errata" was also added as part of the process. If you find other mistakes in the Atlas I would be interested in noting them in the Errata section. You can send comments to: rascwebmaster [at] shaw [dot] ca . Supporting this Publication and our Centre The Calgary Centre of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (http://calgary.rasc.ca/) is a registered Canadian charitable organization with a very active Public Outreach program.