DEAN GARY R. ROBERTS Indiana Law Review Volume 47 2014 Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

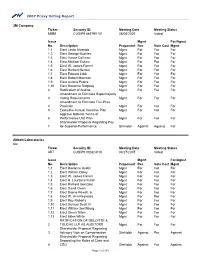

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Report of Investigation

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Special Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation of Citigroup, Inc. Case No. OIG-559 September 27,2011 This document is subjed to the provisions of th e Privacy Act of 1974, and may require redadion before disdosure to third parties. No redaction has betn performed by the Office of Inspedor Gmeral. Recipients of this report should not disseminate or copy it without the Inspector General's approval. " Report of Investigation Cas. No. OIG-559 Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Speeial Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation ofCitigroup, Inc. Table of Contents Introduction and Summary of Results ofthe Investigation ......................................... ..... .. I Scope of the Investigation................................................................................................... 2 Relevant Statutes, Regulations and Pol icies ....................................................................... 4 Results of the Investigation................................................. .. .............................................. 5 I. The Enforcement Staff Investigated Citigroup and Considered Various Charges and Settlement Options ........................................................................................... 5 A. The Enforcement Staff Opened an Investigation -

Special Committee Report

REPORT OF THE 2009 SPECIAL REVIEW COMMITTEE ON FINRA’S EXAMINATION PROGRAM IN LIGHT OF THE STANFORD AND MADOFF SCHEMES SEPTEMBER 2009 SPECIAL REVIEW COMMITTEE Charles A. Bowsher (Chairman) ———————————— Ellyn L. Brown ———————————— Harvey J. Goldschmid ———————————— Joel Seligman ———————————— INDUSTRY GOVERNOR ADVISERS OF COUNSEL Mari Buechner Paul V. Gerlach W. Dennis Ferguson Griffith L. Green G. Donald Steel Dennis C. Hensley Michael A. Nemeroff SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP 1501 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20005 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 1 A. The Stanford Case................................................................................................. 2 B. The Madoff Case................................................................................................... 4 C. Recommendations................................................................................................. 6 II. BACKGROUND ON FINRA EXAMINATION PROGRAM...................................... 9 III. EXAMINATIONS OF MEMBER FIRMS INVOLVED IN THE STANFORD AND MADOFF SCANDALS.................................................................. 11 A. The Stanford Case............................................................................................... 12 1. Background............................................................................................... 12 2. Daniel Arbitration and 2003 Cycle Examination...................................... 13 3. 2003 -

Stanford Ponzi Scheme: Lessons for Protecting Investors from the Next Securities Fraud

THE STANFORD PONZI SCHEME: LESSONS FOR PROTECTING INVESTORS FROM THE NEXT SECURITIES FRAUD HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MAY 13, 2011 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 112–30 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 66–868 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 17:24 Aug 25, 2011 Jkt 066868 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\DOCS\66868.TXT TERRIE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama, Chairman JEB HENSARLING, Texas, Vice Chairman BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts, Ranking PETER T. KING, New York Member EDWARD R. ROYCE, California MAXINE WATERS, California FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York RON PAUL, Texas LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina JUDY BIGGERT, Illinois GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York GARY G. MILLER, California BRAD SHERMAN, California SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JOHN CAMPBELL, California CAROLYN MCCARTHY, New York MICHELE BACHMANN, Minnesota JOE BACA, California THADDEUS G. McCOTTER, Michigan STEPHEN F. -

The TJX Companies, Inc. (Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant x Filed by a Party other than the Registrant o Check the appropriate box: x Preliminary Proxy Statement o Definitive Proxy Statement o Definitive Additional Materials o Soliciting Material Pursuant to §240.14a-11(c) or §240.14a-12 o Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) The TJX Companies, Inc. (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): x No fee required. o Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. 1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: 2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: 3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (Set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): 4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: 5) Total fee paid: o Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. o Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. 1) Amount Previously Paid: 2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: 3) Filing Party: 4) Date Filed: Table of Contents 770 Cochituate Road Framingham, Massachusetts 01701 April , 2005 Dear Stockholder: We cordially invite you to attend our 2005 Annual Meeting on Tuesday, June 7, 2005, at 11:00 a.m., to be held in The Ben Cammarata Auditorium, located at our offices, 770 Cochituate Road, Framingham, Massachusetts. -

Lbex-Am 008597

CITIGROUP AGENDA Meeting Bank Participants Address Lehman's operating performance and risk management practices. • Introduce Brian Leach, CRO, who is new at Citi and in his role, to Ian and Paolo, as well as to the Firm. LBEX-AM 008597 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. Lehman Agenda NETWORK MANAGEMENT • Citi is ranked #1 in Asia, #2 in the US, and #3 in Europe in total operating fees paid by LEH. Fees exceed $30 MM p.a. Citi has been# 1 on the short list to be awarded new operating business due to to the substantial credit support provided until its action of June 12. Most recently, Citi was awarded our Brazilian outsourcing. Brian R. Leach Chief Risk Officer Citi Brian Leach assumed the role of Chief Risk Officer in March 2008, reporting to Citi's Chief Executive Officer, Vikram Pandit. Brian is also the acting Chief Risk Officer for the Institutional Clients Group. Citi is a leading global financial services company and has a presence in more than 100 countries, representing 90% of the world's GOP. The Citi brand is the most recognized in the financial services industry. Citi is known around the world for market leadership, global product excellence, outstanding talent, strong regional and product franchises, and commitment to providing the highest-quality service to its clients. Prior to becoming Citi's Chief Risk Officer, Brian was the co-COO of Old Lane. Brian, along with several former colleagues from Morgan Stanley, founded Old Lane LP in 2005. Earlier, he had worked for his LBEX-AM 008598 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. -

Merging the SEC and CFTC - a Clash of Cultures

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2009 Merging the SEC and CFTC - A Clash of Cultures Jerry W. Markham Florida International University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerry W. Markham, Merging the SEC and CFTC - A Clash of Cultures, 78 U. Cin. L. Rev. 537, 612 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Jerry W. Markham, Merging the SEC and CFTC - A Clash of Cultures, 78 U. Cin. L. Rev. 537 (2009) Provided by: FIU College of Law Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue May 1 10:36:12 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device MERGING THE SEC AND CFTC-A CLASH OF CULTURES Jerry W. Markham* I. INTRODUCTION The massive subprime losses at Citigroup, UBS, Bank of America, Wachovia, Washington Mutual, and other banks astounded the financial world. Equally shocking were the failures of Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and Bear Steams. -

Yom Kippur Morning 5770 Lehman Brothers, Failed

YOM KIPPUR MORNING 5770 LEHMAN BROTHERS, FAILED BANKS, UNEMPLOYMENT, CITIBANK, ALLEN STANFORD, AIG, MARC DREIER, THE SEC, BEAR STEARNS, BAIL OUTS, BANKRUPTCIES, UNEMPLOYMENT, JAMES NICHOLSON, DELAYED RETIREMENTS, BANK OF AMERICA, UBS. BERNIE MADOFF, GREED IS GOOD, FINANCIAL MELTDOWN, MERRILL LYNCH, SUB-PRIME MORTGAGE LOANS, CALIFORNIA GOING BROKE. NON-PROFITS GOING BROKE, 401K’s DISAPPEARING, WALL STREET, TARP AND GREED, INVESTMENT BANKING IS ALL WE NEED. ECONOMY IN A FREEFALL, ECONOMY IN NEAR COLLAPSE, SUICIDE AND HEDGE FUNDS, PLUNGING HOME VALUES. THE IRS BANK FAILURES, DELAYED RETIREMENT, GM STOCK SELLING FOR A DOLLAR, STIMULUS PACKAGE, JOBS DISAPPEARING, COLLEGE ENDOWMENT FUNDS ARE SLASHED FRANK DIPASCALI, PONZI SCHEMES, CHURCH PONZI SCHEMES, AFRICAN PONZI SCHEMES, JEWISH PONZI SCHEMES, PONZI, PONZI, PONZI, BERNIE MADOFF My son David will tell you that the wildest roller coaster rides in the country are at Cedar Point Amusement Park in Sandusky, Ohio. However, looking at the American economy these past two years, we know that there have been some pretty wild rides here as well and, unlike the amusement park, these rides don’t end after two minutes. The last year and a half of the Bush Administration was a terrifying freefall. Not necessarily because of the wrong decisions being made; it just seemed that no one was in charge. No one spoke up. No one acted. No one took responsibility and the economy seemed to careen closer to the edge of the cliff with every passing day. The only real option for whoever won the Presidential election was to actually do something. Our congregants and our community, like most other congregations and communities, have been deeply affected by the events of the past two years. -

Confidential-Sample Chapters Full Text On

CONFIDENTIAL-SAMPLE CHAPTERS FULL TEXT ON REQUEST Praise for $uperHubs “In $uperHubs, Ms. Navidi skillfully applies network science to the global finan- cial system and the human networks that underpin it. $uperHubs is a topical and relevant book that should be read by anyone seeking a fresh perspective on the human endeavor that is our financial system.” CONFIDENTIAL-SAMPLE—PROFESSOR LAWRENCE H. SUMMERS, CHAPTERS Harvard; former US Secretary of the Treasury, former Director of the US National Economic Council, former president of Harvard University, and author “Sandra Navidi’s book $uperHubs is beautifully and effectively done. Not only is it a fascinating description of the power wielded by elite networks over the financial sector, it is also a meditation on the consequences of this system for FULLthe economy TEXT and the society. ON In recentREQUEST times, we have seen extraordinary rup- tures—notably Britain’s vote to break away from the European Union and the intensified sense of exclusion felt by much of America’s working class. The last chapter of $uperHubs proposes that this ruling system›s “monoculture,” its iso- lation from the rest of society, and its seeming unawareness of the fragility of what it has built are largely responsible for these ruptures, and that the system may lead to a major crisis in the future.” —PROFESSOR EDMUND S. PHELPS, Columbia University, 2006 Nobel Prize in Economics; Director, Center on Capitalism and Society, and author “$uperHubs” is a book written with great style but also containing a lot of impor- tant substance. The style is so engaging, a real page turner, that I finished it in one non-stop session. -

IMF 6Th Statistical Forum Agenda and Bios

TH IMF Statistical Forum 6 WASHINGTON, D.C. MEASURING ECONOMIC WELFARE IN THE DIGITAL AGE: WHAT AND HOW? Nov 19–20, 2018 | Washington, D.C. | IMF Headquarters Follow us on: #StatsForum The IMF Statistical Forum aims to facilitate global dialogue on cutting- edge issues in macroeconomic and financial statistics. It offers a platform to build support for statistical improvements from key stakeholders, including policymakers, data users, academics, compilers and data providers. In its sixth year, the theme of the Forum is “Measuring Economic Welfare in the Digital Age: What and how?” The focus will be on the socio-economic implications of digitalization for welfare, a dimension that often escapes the standard macro- financial indicators, and what should be done to capture it in our statistics. MONDAY, NOVEMBER 19 NOVEMBER MONDAY, AGENDA MONDAY DAY 1 8:00 am Registration and Continental Breakfast 8:45 am Welcoming Remarks, Louis Marc Ducharme, Chief Statistician and Data Officer and Director, Statistics Department, IMF 8:50 am Introduction to the Forum, David Lipton, First Deputy Managing Director, IMF 9:15 am SESSION I: FRAMEWORK FOR ECONOMIC WELFARE “BEYOND GDP”. WHAT IS NEW IN THE DIGITAL AGE? Why do we need measures of welfare that is directly linked to economic progress but not captured by existing national accounts and price statistics? Has the need for indicators of whether growth has been inclusive become more urgent? What about household non-market production (e.g., housekeeping, child care, cooking and services of volunteers)? Has -

Q4 2007 Citigroup Inc. Earnings Conference Call on Jan. 15. 2008

FINAL TRANSCRIPT C - Q4 2007 Citigroup Inc. Earnings Conference Call Event Date/Time: Jan. 15. 2008 / 8:30AM ET www.streetevents.com Contact Us © 2008 Thomson Financial. Republished with permission. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Thomson Financial. FINAL TRANSCRIPT Jan. 15. 2008 / 8:30AM, C - Q4 2007 Citigroup Inc. Earnings Conference Call CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Art Tildesley Citigroup Inc. - IR Vikram Pandit Citigroup Inc. - CEO Gary Crittenden Citigroup Inc. - CFO CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Guy Moszkowski Merrill Lynch - Analyst Betsy Graseck Morgan Stanley - Analyst William Tanona Goldman Sachs - Analyst Mike Mayo Deutsche Bank - Analyst Meredith Whitney Oppenheimer - Analyst Glenn Schorr UBS - Analyst Richard Bove Punk, Ziegel - Analyst David Hilder Bear Stearns - Analyst PRESENTATION Operator Good morning, ladies and gentlemen and welcome to Citi©s fourth-quarter and full-year 2007 earnings review featuring Citi Chief Executive Officer, Vikram Pandit and Chief Financial Officer, Gary Crittenden. Today©s call will be hosted by Art Tildesley. We ask that you hold all questions until the completion of the formal remarks at which time you will be given instructions for the question and answer session. Also, as a reminder, this conference is being recorded today. If you have any objections, please disconnect at this time. Mr. Tildesley, you may begin. Art Tildesley - Citigroup Inc. - IR Thank you very much, operator and thank you all for joining us this morning. Welcome to our fourth-quarter 2007 earnings presentation. The presentation that we will be walking through is available on our website, so you will want to download that now if you haven©t already done so. -

Super Regulators?

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 28 Issue 2 SYMPOSIUM: Do Financial Supermarkets Need Article 4 Super Regulators? 2003 Super Regulator: A Comparative Analysis of Securities and Derivatives Regulation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan Jerry W. Markham Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Jerry W. Markham, Super Regulator: A Comparative Analysis of Securities and Derivatives Regulation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan, 28 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2003). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol28/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. File: Markham Base Macro Final.doc Created on: 3/20/2003 5:05 PM Last Printed: 4/28/2003 11:3 1 AM SUPER REGULATOR: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SECURITIES AND DERIVATIVES REGULATION IN THE UNITED STATES, THE UNITED KINGDOM, AND JAPAN Jerry W. Markham* I. INTRODUCTION he value of competition among regulators has been the T subject of debate in the United States (“U.S.”) for some time.1 On the one hand, its advocates contend that com- peting regulatory bodies will not only govern less, but also more efficiently.2 Proponents of centralized regulation, on the other hand, argue that ove rlapping regulation is costly, inefficient, and allows exploitation and abuses along regulatory seams.3 In supporting their arguments, however, both sides of this debate rely largely on intuitive arguments or anecdotal evidence.