Water Recycling: Recent History of Local Government Initiatives in South East Queensland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Public Boat Ramps

Queensland public boat ramps Ramp Location Ramp Location Atherton shire Brisbane city (cont.) Tinaroo (Church Street) Tinaroo Falls Dam Shorncliffe (Jetty Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank Balonne shire Shorncliffe (Sinbad Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank St George (Bowen Street) Jack Taylor Weir Shorncliffe (Yundah Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank Banana shire Wynnum (Glenora Street) Wynnum Creek—north bank Baralaba Weir Dawson River Broadsound shire Callide Dam Biloela—Calvale Road (lower ramp) Carmilla Beach (Carmilla Creek Road) Carmilla Creek—south bank, mouth of creek Callide Dam Biloela—Calvale Road (upper ramp) Clairview Beach (Colonial Drive) Clairview Beach Moura Dawson River—8 km west of Moura St Lawrence (Howards Road– Waverley Creek) Bund Creek—north bank Lake Victoria Callide Creek Bundaberg city Theodore Dawson River Bundaberg (Kirby’s Wall) Burnett River—south bank (5 km east of Bundaberg) Beaudesert shire Bundaberg (Queen Street) Burnett River—north bank (downstream) Logan River (Henderson Street– Henderson Reserve) Logan Reserve Bundaberg (Queen Street) Burnett River—north bank (upstream) Biggenden shire Burdekin shire Paradise Dam–Main Dam 500 m upstream from visitors centre Barramundi Creek (Morris Creek Road) via Hodel Road Boonah shire Cromarty Creek (Boat Ramp Road) via Giru (off the Haughton River) Groper Creek settlement Maroon Dam HG Slatter Park (Hinkson Esplanade) downstream from jetty Moogerah Dam AG Muller Park Groper Creek settlement Bowen shire (Hinkson -

Download Legal Knowledge Matters 2006

Planning Government Infrastructure and Environment group Colin Biggers & Paisley's Planning Government Infrastructure and Environment group is the trusted partner of public and private sector entities, for whom we are the legal and policy designers of strategic and tactical solutions to exceptionally challenging problems, in our chosen fields of planning, government, infrastructure and environment. We have more than 50 years' experience of planning, designing and executing legal and policy solutions for large development and infrastructure projects in Australia, including new cities, towns and communities. We are passionate about planning, government, infrastructure and environment issues, and we pride ourselves on acting for both the private and public sectors, including private development corporations, listed development corporations, other non-public sector entities and a wide range of State and local government entities. The solutions we design extend beyond legal and policy advice, and represent sensible, commercially focused outcomes which accommodate private interests in the context of established public interests. Reputation Our Planning Government Infrastructure and Environment group has built long and trusted relationships through continuous and exceptional performance. We understand that exceptional performance is the foundation of success, and we apply our philosophy of critical thinking and our process of strategy to ensure an unparalleled level of planning, design and manoeuvre to achieve that success. Our group practices as an East Coast Team of Teams, known for its Trusted Partners, Strategic Thinkers, Legal and Policy Designers and Tacticians. Credo Our credo is to Lead, Simplify and Win with Integrity. Our credo means we partner by integrity, lead by planning, simplify by design and win by manoeuvre. -

Queensland Act of 1952.”

74 ELECTRICITY. Southern Electric Authority of Queensland Act. 1 Eliz. II. No. 50, ELECTRICITY. 1 ^iz5oil An Act to constitute the Southern Electric Authority Southern of Queensland, and for other purposes. Electric . A x Authority qubensiand [Assented to 18th December, 1952.] Act of 1952. E it enacted by the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Legis Blative Assembly of Queensland in Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— Part I — Preliminary-. PART I.---PRELIMINARY. Short title. This Act may be cited as “ The Southern Electric Authority of Queensland Act of 1952.” 2. This Act is divided into Parts as follows :— Part I.—Preliminary ; Part II.—Constitution of the Authority ; Part III.—Acquisition by Authority of Electric Authorities ; Division I.—Acquisition by Agreement; Division II.—City Electric Light Company Limited ; Division III.—Electric Authorities other than Local Authorities; Division IV.—Local Authorities ; Part IV.—Finance and Accounts ; Division I.—Accounts and Audit; Division II.—Interest During Construction ; Division III.—Loans and Deposits ; Division IV.—Variable Interest Stock ; Division V.—Secured Debentures and Stock ; Division VI.—Budget ; Part V.—Powers and Duties of the Authority ; Part VI.—Offences and Legal Proceedings ; Part VII.—Miscellaneous. ELECTRICITY. 75 Part I.—- 1952. Southern Electric Authority of Queensland Act. Preliminary. 3. In this Act unless the context otherwise indicates interpreta- or requires, the following terms shall have the meanings definitions, set against them respectively, that is to say :— “ The Agreement ” means the agreement between Agreement, the State of Queensland and the Authority a copy of which is set out in the Second Schedule to this Act; ■ “ Area of supply ” means the area in which the Area of Authority is for the time being authorisedsupply- to supply electricity; “Authority” means The Southern Electric Authority. -

Strategic Context

11,200 Residents The Airport Strategic Context Project 16,800 Residents Major Development Area Recreational/Tourism Zones Nambour Landsborough Local Plan Area Boundary MAROOCHY RIVER Landsborough Study Area Area of Significant Population Maroochydore Water Body MAROOCHYDORE RD Train Line SUNSHINE MOTORWAY Kondalilla 7,700 National Park Hinterland & Elevation Residents Buderim Mooloolaba Sunshine Coast Palmwoods BRUCE HIGHWAY LAKE BAROON SUNSHINE MOTORWAY 303,400 Dularcha MOOLOOLAH RIVER National Park Estimated Current University of the Residents (2016) Sunshine Coast NICKLIN WAY The Space Mooloolah River Between National Park 70,000 MALENY STREET LAKE KAWANA Landsborough 18,000 Estimated Sportsgrounds Estimated Residents Residents by 2026 40MIN Palmview BY CAR TO Landsborough State FUTURE CITY Primary School Peace Memorial CENTRE Sunshine Coast 3,700 CRIBB STREET University Hospital Residents Park CALOUNDRA STREET Maleny Landsborough Train Station Pioneer Park MOOLOOLAH RIVER Coast & Landsborough Bus Station EWEN MADDOCK DAM 23% Coastal Plain Landsborough STEVE IRWIN WAY Estimated Population Landsborough Police Station CALOUNDRA ROAD Increase by 2026 Beerburrum15MIN Beerwah State Forest LITTLE ROCKY CREEK StateBY Forest CAR TO MELLUM CREEK MALENY 3,900 Residents Big Kart Track 3,800 Caloundra STEVE IRWIN WAY Rocky Creek Residents STEVE IRWIN WAY Camp Site Landsborough BRUCE HIGHWAY Skippy Park 50,000 LAKE MAGELLAN Estimated Residents Caloundra South Australia Zoo 50,000 Estimated Residents Beerwah East 6,800 1.25HRS Residents BY CAR TO BRISBANE Beerwah Setting the The rural township of Scene Landsborough is situated at the southern entrance of the Blackall Range with the areas surrounding the township being rural residential and rural lands. This regional inter-urban break is a significant feature that frames the township and shapes its identity. -

Hydrological Advice to Commission of Inquiry Regarding 2010/11 Queensland Floods

Hydrological Advice to Commission of Inquiry Regarding 2010/11 Queensland Floods TOOWOOMBA AND LOCKYER VALLEY FLASH FLOOD EVENTS OF 10 AND 11 JANUARY 2011 Report to Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry Revision 1 12 April 2011 Hydrological Advice to Commission of Inquiry Regarding 2010/11 Queensland Floods TOOWOOMBA AND LOCKYER VALLEY FLASH FLOOD EVENTS OF 10 AND 11 JANUARY 2011 Revision 1 11 April 2011 Sinclair Knight Merz ABN 37 001 024 095 Cnr of Cordelia and Russell Street South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia PO Box 3848 South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Tel: +61 7 3026 7100 Fax: +61 7 3026 7300 Web: www.skmconsulting.com COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Sinclair Knight Merz constitutes an infringement of copyright. LIMITATION: This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd’s Client, and is subject to and issued in connection with the provisions of the agreement between Sinclair Knight Merz and its Client. Sinclair Knight Merz accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley Flash Flood Events of 10 and 11 January 2011 Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 1.1 Description of Flash Flooding in Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley1 1.2 Capacity of Existing Flood Warning Systems 2 1.3 Performance of Warnings -

Queensland Government Gazette

Queensland Government Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. CCCXXXVIII] (338) FRIDAY, 18 FEBRUARY, 2005 BUUIJTSBUF ZPVDBOBGGPSE UPSFTUFBTZ /VERLOOKINGTHE"OTANIC'ARDENSANDRIVER "RISBANES 2OYALONTHE0ARKISJUSTASHORTSTROLLFROM0ARLIAMENT(OUSE AND'OVERNMENTOFlCESIN'EORGE3TREETD !TTHISRATE ITCOULDBEYOURHOMEAWAYFROMHOME PERROOM PERNIGHT 'OVERNMENTRATEINCLUDES #NR!LICEAND!LBERT3TREET"RISBANE#ITY s&REENEWSPAPER 0HONE&AX &ULLBUFFETBREAKFASTISAVAILABLE 3UBJECTTOAVAILABILITY3INGLE TWINORDOUBLEOCCUPANCY 0RICEINCLUDES'346ALIDTILL FORANADDITIONALPERPERSON 2/0OI Extraordinary Gazette No. 33 Friday 18th February 2005 is currently unavailable, SDS apologises for any inconvenience caused. Please contact the Gazette Administrator on (07) 3866 022. [529] Queensland Government Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. CCCXXXVIII] (338) FRIDAY, 18 FEBRUARY, 2005 [No. 34 KINGAROY SHIRE COUNCIL Local Government Act 1993 Notice is hereby given that on 18 March 2004 (Stages 1-3) and 25 CAIRNS CITY COUNCIL November 2004 (Stage 4) Kingaroy Shire Council adopted a (MAKING OF LOCAL LAW) consequential amendment to it s Transitional Planning Scheme. NOTICE (No. 2) 2005 The purpose of the amendment is to reflect a Development Permit (Material Change of Use) to change the zone of part of the land Short Title from Rura l A to Residential A at premises describ ed as Lot 20 1. This notice may be cited as Cairns City Council (Making of RP848606, 141 Moore Street, Kingaroy, Parish of Wooroolin. Local Law) Notice (No. 2) 2005. Copies of the amendment are available for inspection and purchase Commencement at the Council Chambers, Glendon Street, Kingaroy. 2. This notice commences on the date it is published in the Gazette. R. TURNER CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Making of Local Law 3. Pursuant to the provisions of the Local Government Act 1993, Cairns City Council made Vegetation Protection (Amendment) Local Law (No. -

Caboolture Shire Handbook

SHIRE HANDBOOK CABOOLTURE QUEENSLAND DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES LIMITED DISTRIBUTION - GOV'T.i 1NSTRUHENTALITY OFFICERS ONLY CABOOLTURE SHIRE HANDBOOK compiled by G. J. Lukey, Dipl. Trop. Agric (Deventer) Queensland Department of Primary Industries October 1973. The material in this publication is intended for government and institutional use only, and is not to be used in any court of law. 11 FOREWORD A detailed knowledge and understanding of the environment and the pressures its many facets may exert are fundamental to those who work to improve agriculture, or to conserve or develop the rural environment. A vast amount of information is accumulating concerning the physical resources and the farming and social systems as they exist in the state of Queensland. This information is coming from a number of sources and references and is scattered through numerous publications and unpublished reports. Shire Handbooks, the first of which was published in February 1969, are an attempt to collate under one cover relevant information and references which will be helpful to the extension officer, the research and survey officer or those who are interested in industry or regional planning or in reconstruction. A copy of each shire handbook is held for reference in each Division and in each Branch of the Department of Primary Industries in Brisbane. In addition Agriculture Branch holds at its Head Office and in each of its country centres, Shire Handbooks, Regional Technical Handbooks (notes on technical matters relevant to certain agricultural industries in the Shire) and monthly and annual reports which are a continuing record of the progress and problems in agriculture. -

Hansard 14 May 1996

Legislative Assembly 993 14 May 1996 TUESDAY, 14 MAY 1996 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS In accordance with the schedule circulated by the Clerk to members in the Chamber, the following documents were Mr SPEAKER (Hon. N. J. Turner, Nicklin) tabled— read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. Acts Interpretation Act 1954— Criminal Code Regulation 1996, No. 84 ASSENT TO BILLS Coal Industry (Control) Act 1948— Assent to the following Bills reported by Coal Industry (Control) Amendment Mr Speaker— Regulation (No. 2) 1996, No. 92 Constitution (Parliamentary Secretaries) Coal Mining Act 1925— Amendment Bill; Coal Mining (Moranbah North) Exemption Courts (Video Link) Amendment Bill; Order 1996, No. 91 Choice of Law (Limitation Periods) Bill; Crimes (Confiscation) Act 1989— Local Government Amendment Bill; Crimes (Confiscation) Regulation 1996, Land Amendment Bill; No. 89 Land Title Amendment Bill; Criminal Code [1995]— Education (Work Experience) Bill. Criminal Code Regulation 1996, No. 84 Electricity Act 1994— Electricity Amendment Regulation (No. 1) PETITIONS 1996, No. 86 The Clerk announced the receipt of the Hospitals Foundations Act 1982— following petitions— Hospitals Foundation (Townsville General Hospital Foundation) Rule 1996, No. 90 Homosexuals, Legislation Lotteries Act 1994— From Mr Carroll (1,109 signatories) Lotteries Rule 1996, No. 93 requesting the House to reject the Queensland Cement & Lime Company Limited Commonwealth Powers (Amendment) Bill or Agreement Act 1977— any similar Queensland legislation that might Queensland Cement & Lime Company either refer to the Federal Government the Limited Agreement Amendment Order State powers over property rights of "defacto (No. 1) 1996, No. 85 marriage" parties or homosexual pairs or State Development and Public Works create any additional rights for homosexuals. -

Capricorn Coast Regional Council & Rockhampton Regional Council

Capricorn Coast Regional Council & Rockhampton Regional Council a Partnership Approach for Sound Regional Governance Unity and strength with community of interest representation De-amalgamation Submission to the Queensland Boundary Commissioner August 2012 Contents CCIM Message 2 Preface . 3 Response to Boundary Commission Questions 6 Bernard Salt - A Precis 11 Capricorn Coast - A Regional Growth Centre . .13 Financial Viability Analysis 14 Livingstone/Capricorn Coast Regional Council Profile in the Regional Context 19 Economic Development 21 Optimum Service Delivery 30 Optimum Governance Model 35 Communities of Interest 37 Amalgamation Impacts on Community Services . .44 Capricorn Coast Independence Movement Environmental Management 47 PO Box 309 Yeppoon Qld 4703 Contact: Paul Lancaster, Chairman Appendices . .54 Phone: 07 4939 7840 Email: [email protected] Contact: Cr Bill Ludwig Phone: 0428 791 792 Email: [email protected] 1 CCIM Message The two primary objectives that will be achieved by restoring an independent Capricorn Coast Regional Council are as follows. The first is to restore the fundamental and basic democratic rights of every community to make their own decisions about determining their future, and setting their own priorities while considering the broader Regional context. The second, and equally important, is delivering a better model of Local Government to provide for sound decision making, while empowering our business, industry and primary producers with a better focussed and a more inclusive ‘grassroots’ foundation from which to promote and enhance regional economic growth and prosperity. These combined objectives will ensure the proposed Capricorn Coast Regional Council area can realise and optimise its full potential in partnership with the greater Rockhampton area. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1960

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly THURSDAY, 10 NOVEMBER 1960 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy 1344 Auctioneers, Real Estate, &c., Bill [ASSEMBLY] Questions THURSDAY, 10 NOVEMBER, 1960 Mr. SPEAKER (Hon. D. E. Nicholson, Murrumba) took the chair at 11 a.m. QUESTIONS INCREASES IN BRISBANE MEAT PRICES Mr. LLOYD (Kedron) asked the Minister for Agriculture and Forestry- "(!) Has his attention been drawn to what is apparently a deliberately misleading opinion in the 'Telegraph' of Tuesday, November 8, which attempts to place the responsibility for the seven pence increase in meat prices in Brisbane on the control over the supply of meat in the metropolitan area by the Brisbane Abattoir?" "(2) Is it not a fact that the Cannon Hill Saleyards are merely a facility placed at the disposal of the buyers and sellers of cattle and the Queensland Meat Industry Board has nothing to do with the prices paid for the cattle sold at the Saleyards?" "(3) Would it not be true to state that the only affect that the operations of the Brisbane Abattoir have on the price of meat to the Brisbane housewife is the charge per head imposed on the slaugh tering of cattle owned by meat companies and individual buyers?" "(4) For the correct information of the Brisbane public, will he outline the charges made for the slaughtering of cattle at the Brisbane Abattoir?" "(5) How do these charges compare with those imposed by other abattoirs?" Questions [10 NOVEMBER] Questions 1345 "(6) Has there been any recent increase Cannon Hill have had no influence on in the slaughtering charges levied at the recent rises in meat prices. -

Cabinet Minute Decision No

CABINET MINUTE DECISION NO. BRISBANE, /2- / ~..2 /19 f>,f' SUBJECT: _________________________________ Supply of Pasteurised Milk and Cream Withi n Localitie s Prescribed - Milk Supply Act 1977-1986. ________________________,( Subm ission No. JO.;/ 7/7 ) y...Fr( J'o Copies Received at ,t"00 p.m. r'lpies 1de CIRCULATION DETAILS 1 GOVERNOR 21 Decision I ile 2 22 MR. AHERN ~ p (,~. 1~ ·1·9l 3 MR. GUNN 23 4 MR. GIBBS 24 5 MR. GLASSO N 25 6 MR. AUSTit 26 7 MR. LESTEB 27 8 28 MR. TENNI 9 MR. HARPEB 29 10 MR. MUNTZ 30 11 31 MR. MC'l(F'ri-: NIP. 12 32 MR. KATTEF --- 13 MR. NEAL 33 14 MR. CLAUSC N 34 ·- MR. BORBII: GE i 15 35 16 MR. RANDEI L 36 17 MR. COOPEF 37 --'-- - MRS. HARVE y 18 38 19 MR. LITTLE PROUD 39 -- ~ 20 Master Fi] e 40 incties cm , 1 12 Kodak Color Control Patcnes.: Blue Cyan Green Copy No. 20 C O N F I D E N T I A L C A B I N E T M I N U T E Brisbane, 12th December, 1988 Decision No. 55776 Submission No. 50278 TITLE: Supply of Paste urised Milk and Cre am within Local i ties Prescribe d - Milk Supply Act 1977-1986 0 CABINET decided~- That it be recommended to the Gove rnor in Council for the Order in Council attached to the Submission to be approve d. CIRCULATION: Department of Primary Industries and copy to Ministe r o All other Ministers for pe rusal and r e turn. -

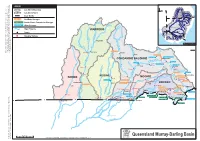

Queensland Murray-Darling Basin Catchments

LEGEND Catchment Boundary Charleville PAROO Catchment Name Roma Toowoomba St George State Border ondiwindi QUEENSLAND Go Leslie Dam SunWater Storages Brewarrina Glenlyon Dam Border Rivers Commission Storages Nygan Cooby Dam Other Storages Broken Hill Menindee NEW SOUTH WALES Major Streams SOUTH WARREGO AUSTRALIA Towns Canberra VICTORIA bury Gauging Stations Al ndigo Be Nive River Ward River Ward Augathella L Murray Darling Basin a Maranoa n g lo R Bungil Ck While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this product, Department Environment and Resource iv River er Neil Turner Weir Disclaimer: completeness or suitability for any particular reliability, Management makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, purpose and disclaims all responsibility liability (including without limitation, in negligence) for expenses, losses, or incomplete in any way and for reason. damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which you might incur as a result of the product being inaccurate Binowee Charleville Mitchell Roma Chinchilla Weir Creek Gilmore Weir Charleys Creek Weir Chinchilla CONDAMINE BALONNE k gw oo d C Warrego o D Warra Weir Surat Weir Brigalow Condamine Weir C River Creek o Loudon Weir reviR reviR Cotswold n Surat d Dalby a Wyandra Tara m r e i iv n Fairview Weribone e R Ck e Oak ey n Creek n o Cecil Weir Cooby Dam l a Wallen B Toowoomba Lemon Tree Weir NEBINE Cashmere River PAROO MOONIE Yarramalong Weir Cardiff R iv Tummaville Bollon Weir Beardmore Dam Moonie er Flinton River Talgai Weir Cunnamulla