Description of Sussex County Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPEN SPACE and RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex Compiled by The Land Conservancy with Township of Green of New Jersey Open Space Committee A nonprofit land trust May 2009 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex Compiled by The Land Conservancy of Township of Green New Jersey with Open Space Committee a nonprofit land trust May 2009 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex Produced by: The Land Conservancy of New Jersey Partners for Greener Communities Team: “Partnering with Communities to Preserve Natural Treasures” David Epstein, President Barbara Heskins Davis, AICP/P.P., Vice President, Programs Holly Szoke, Communications Director Kenneth Fung, GIS Manager Samantha Rothman, Planning Consultant Casey Dziuba, Planning Intern For further information please contact: The Land Conservancy of New Jersey Township of Green 19 Boonton Avenue Open Space Committee Boonton, NJ 07005 150 Kennedy Road (973) 541-1010 Andover, NJ 07821 Fax: (973) 541-1131 (908) 852-9333 www.tlc-nj.org Fax: (908) 852-1972 www.greentwp.com Copyright © 2009 All rights reserved Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form without prior consent May 2009 . Acknowledgements The Land Conservancy of New Jersey wishes to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their help in providing information, guidance, and materials for the Green Township Open Space and Recreation Plan Update. Their contributions have been instrumental -

Kittatinny Valley Is the Name Given to That Part of the Great Appala Chian Valley

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA PALEOZOIC LIMESTONES OF KITTATINNY VALLEY, NEW J E R S E Y * BY HENRY B. KUMMEL AND STUART WELLER ( Read before the Society December 28, 1900) CONTENTS P a g e Kittatinny valley............................................................................................................... 147 Hardiston quartzite........................................................................................................... 149 Relations and character............................................................................................ 149 Previous views............................................................................................................. 151 Kittatinny limestone......................................................................................................... 151 Stratigraphic and macroscopic characters............................................................ 151 Chemical composition................................................................................................ 152 Fauna of the Kittatinny lim estone........................................................................ 152 Previous views............................................................................................................. 154 Trenton formation............................................................................................................. 154 Basal conglomerate............................................................................................................ -

2020 Freshwater Fishing Digest Pages 16-33

License Information 2020 REGULATIONS Regulations in red are new this year. New Jersey National Guard Summary of General Only New Jersey National Guard personnel in good Licenses standing are entitled to free sporting licenses, per- Fishing Regulations mits and stamps. These privileges are not available The season, size and creel limits for freshwater • A valid New Jersey fishing license is required for using Fish and Wildlife’s website. However, the NJ species apply to all waters of the state, including residents at least 16 years and less than 70 years Dept. of Military and Veterans Affairs can issue tidal waters. of age (plus all non-residents 16 years and older) fishing licenses through their DMAVA website at • Fish may be taken only in the manner known as to fish the fresh waters of New Jersey, includ- www.nj.gov/military/iasd/fishing.html. For all other angling with handline or with rod and line, or ing privately owned waters. See page 17 for free sporting licenses, call (609) 530-6866, email as otherwise allowed by law. information on the money-saving Buddy Fish- [email protected], or write to: MSG (Ret.) • When fishing from the shoreline, no more than ing License, coming to Internet sales in 2020. Robert Greco, NJ DMAVA, 101 Eggert Crossing three fishing rods, handlines or combination • For fishing-related license and permit fees, see Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648. thereof may be used (except on the Delaware page 1. River. There is no rod limit when fishing from • Resident anglers age 70 and over do not require a Disabled Veterans Licenses, a boat except for the Delaware River.) For the fishing license. -

SUSSEX County

NJ DEP - Historic Preservation Office Page 1 of 9 New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places Last Update: 9/28/2021 SUSSEX County Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Lackawanna Cutoff SUSSEX County Historic District (ID#3454) SHPO Opinion: 3/22/1994 Also located in: Andover Borough MORRIS County, Roxbury Township Andover Borough Historic District (ID#2591) SUSSEX County, Andover Borough SHPO Opinion: 10/22/1991 SUSSEX County, Andover Township SUSSEX County, Green Township 20 Brighton Avenue (ID#3453) SUSSEX County, Hopatcong Borough 20 Brighton Avenue SUSSEX County, Stanhope Borough SHPO Opinion: 9/11/1996 WARREN County, Blairstown Township WARREN County, Frelinghuysen Township Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Lackawanna Cutoff WARREN County, Knowlton Township Historic District (ID#3454) SHPO Opinion: 3/22/1994 Morris Canal (ID#2784) See Main Entry / Filed Location: Existing and former bed of the Morris Canal SUSSEX County, Byram Township NR: 10/1/1974 (NR Reference #: 74002228) SR: 11/26/1973 Hole in the Wall Stone Arch Bridge (ID#2906) SHPO Opinion: 4/27/2004 Delaware, Lackawanna, & Western Railroad Sussex Branch over the (Extends from the Delaware River in Phillipsburg Town, Morris and Susses Turnpike west of US Route 206, north of Whitehall Warren County to the Hudson River in Jersey City, Hudson SHPO Opinion: 4/18/1995 County. SHPO Opinion extends period of significance for canal to its 1930 closure.) Pennsylvania-New Jersey Interconnection Bushkill to Roseland See Main Entry / Filed Location: Transmission -

Town of Philipstown Conservation Board 238 Main Street, Cold Spring, Ny 10516

TOWN OF PHILIPSTOWN CONSERVATION BOARD 238 MAIN STREET, COLD SPRING, NY 10516 MEETING AGENDA August 12, 2014 at 7:30 pm 1.) OBERT WOOD TM# 71.-2-39.1 WL-14-241 316 OLD WEST POINT RD INSTALL BURRIED ELECTRIC SERVICE TO A NEW RESIDENCE 2.) BRUCE AND DONNA KEHR TM# 16.20-18,20,&21 PBR TOWN OF PHILIPSTOWN 238 Main Street PUTNAM COUNTY, NEWYORK Cold Spring, NY, 10516 (845) 265-5202 APPLICATION FOR WETLANDS PERMIT· Note to Applicant: . Submit the completed application to the appropriate permitting authoirty. The application for Wetlands Permit should be sumbitte simultaneously with any related application (e.g. subdivision approval, site plan approval, special use permit, etc.) being made to the permitting authority. (Office Use Only) Application # D Permitting Authority Received by: D Z.B.A Date D Planning Board Fee D Wetlands Inspector Pursuant to Chapter 93 of the Code of the Town of Philipstown, entitled "Freshwater Wetlands and Watercourse Law of the Town of Philipstown" (Wetlands Law), the undersigned hereby applies for a Wetlands Permit to conduct a regulated activity in a controlled area. 1. Owner; Name: Obert R. Wood. III Address: 115 East 9th Street, Apt 2M New York, NY 10003 E212~ Telephone: 6298334 0117-6'10- 026g 2. Agent Name: (Applicant must be owner of the land The Application may be managed by an authorized agent of such person possessing a notarized letter of consent from the owner.) Name of Agent If Corporation, give names of officers: Mailing Address _ Telephone: 3. Location of Proposed Activity: 316 Old West Point Road West, Garrison Tax Map No.: 7_1_.-_2_-3_9_._1 _ Acreage of Controlled Area Affected: -------------------0.047 4. -

Wallkill River

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge At the Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge, we conserve the biological diversity of the Wallkill Valley by protecting and managing land, with a special emphasis on s% i 7 7 7* 7 migrating wate / fo wl, wintering raptors, and endangered species, while providing \ opportunities for scientific research J *tind compatible I public use. ' Our Mission Congress established the Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge in 1990 "to preserve and enhance refuge lands and waters in a manner that will conserve the natural diversity of fish, wildlife, plants, This blue goose, and their habitats for present and designed by J.N. future generations and to provide "Ding" Darling, opportunities for compatible has become the scientific research, environmental symbol of the education, and fish and wildlife- National Wildlife oriented recreation." Congress Refuge System. /. also required the protection of •/. aquatic habitats within the refuge, •- including the Wallkill River and '53 Papakating Creek. - The individual purposes of this Wallkill River refuge are supported by the mission in fall The refuge is located along a nine-mile of the National Wildlife Refuge stretch of the Wallkill River, and lies in System, of which the Wallkill River a rolling valley within the Appalachian refuge is a part. That mission is Ridge and Valley physiographic "to administer a national network province. The Wallkill Valley is of lands and waters for the bounded by the Kittatinny Ridge to conservation, management, and the west and the New York/New where appropriate, restoration of Jersey Highlands to the east. This the fish, wildlife, and plant resources area is part of the Great Valley, which and their habitats within the United extends from Canada to the southern States for the benefit of present and United States. -

Sussex County Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN for the County of Sussex “People and Nature Together” Compiled by Morris Land Conservancy with the Sussex County Open Space Committee September 30, 2003 County of Sussex Open Space and Recreation Plan produced by Morris Land Conservancy’s Partners for Greener Communities team: David Epstein, Executive Director Laura Szwak, Assistant Director Barbara Heskins Davis, Director of Municipal Programs Robert Sheffield, Planning Manager Tanya Nolte, Mapping Manager Sandy Urgo, Land Preservation Specialist Anne Bowman, Land Acquisition Administrator Holly Szoke, Communications Manager Letty Lisk, Office Manager Student Interns: Melissa Haupt Brian Henderson Brian Licinski Ken Sicknick Erin Siek Andrew Szwak Dolce Vieira OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN for County of Sussex “People and Nature Together” Compiled by: Morris Land Conservancy a nonprofit land trust with the County of Sussex Open Space Advisory Committee September 2003 County of Sussex Board of Chosen Freeholders Harold J. Wirths, Director Joann D’Angeli, Deputy Director Gary R. Chiusano, Member Glen Vetrano, Member Susan M. Zellman, Member County of Sussex Open Space Advisory Committee Austin Carew, Chairperson Glen Vetrano, Freeholder Liaison Ray Bonker Louis Cherepy Libby Herland William Hookway Tom Meyer Barbara Rosko Eric Snyder Donna Traylor Acknowledgements Morris Land Conservancy would like to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their help in providing information, guidance, research and mapping materials for the County of -

Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 This Blue Goose, Designed by J.N

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 This blue goose, designed by J.N. “Ding” Darling, has become the symbol of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the principal federal agency responsible for conserving, protecting, and enhancing fi sh, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefi t of the American people. The Service manages the 97-million acre National Wildlife Refuge System comprised of more than 548 national wildlife refuges and thousands of waterfowl production areas. It also operates 69 national fi sh hatcheries and 81 ecological services fi eld stations. The agency enforces federal wildlife laws, manages migratory bird populations, restores nationally signifi cant fi sheries, conserves and restores wildlife habitat such as wetlands, administers the Endangered Species Act, and helps foreign governments with their conservation efforts. It also oversees the Federal Assistance Program which distributes hundreds of millions of dollars in excise taxes on fi shing and hunting equipment to state wildlife agencies. Comprehensive Conservation Plans provide long term guidance for management decisions and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes and identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment for staffi ng increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 Submitted by: Edward Henry Date Refuge Manager Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Concurrence by: Janet M. -

November/December 2007

www.nynjtc.org Connecting People with Nature since 1920 November/December 2007 New York-New Jersey Trail Conference — Maintaining 1,700 Miles of Foot Trails In this issue: Crowd Builds RPH Bridge...pg 3 • A Library for Hikers....pg 6 • Are Those Pines Sick, Or What?...pg 7 • Avoid Hunters, Hike Local...pg 12 revamped. There was an enormous amount BELLEAYRE Trail Blazes of Glory of out-blazing the old markers, putting up new markers, closing trails, clearing the By Brenda Freeman-Bates, Senior Curator, Ward Pound Ridge Reservation trails of over-hanging and fallen debris, Agreement Scales reconfiguring trails, walking them in the different seasons, tweaking the blazes, and Back Resort and having a good time while doing it all. A new trail map has also been printed, Protects Over with great thanks and gratitude to the Trail Conference for sharing its GPS database of the trails with the Westchester County 1,400 Acres of Department of Planning. The new color map and brochure now correctly reflect Land in New York N O the trail system, with points of interest, I T A V topographical lines, forests, fields, and On September 5, 2007, Governor Spitzer R E S E wetlands indicated. announced an agreement regarding the R E G This amazing feat would never have been Belleayre Resort at Catskill Park develop - D I R accomplished so expeditiously without the ment proposal after a seven-year legal and D N U dedication of volunteers. To date, a very regulatory battle over the project. The O P D impressive 928.5 volunteer hours have agreement between the project sponsor, R A W : been recorded for this project. -

Prepared in Cooperation with the Trenton, New Jersey August 1982

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DRAINAGE AREAS IN NEW JERSEY: DELAWARE RIVER BASIN AND STREAMS TRIBUTARY TO DELAWARE BAY By Anthony J. Velnich OPEN-FILE REPORT 82-572 Prepared in cooperation with the UNITED STATES ARMY, CORPS OF ENGINEERS, PHILADELPHIA DISTRICT and the NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION, DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCES Trenton, New Jersey August 1982 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information write to District Chief, Water Resources Division U.S. Geological Survey Room 430, Federal Building 402 East State Street Trenton, New Jersey 08608 CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction--- - ---- -- --- ---- -- - - -- -- 1 Determination of drainage areas 3 Explanation of tabular data- 3 References cited 5 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Map showing location of Delaware River basin and Delaware Bay drainage divides in New Jersey 2 TABLES Table 1. Drainage areas at stream mouths in New Jersey, in the Delaware River basin, including tributaries to Delaware Bay 6 2.--Drainage areas at selected sites on New Jersey streams tributary to, and including the Delaware River- 15 3. Drainage areas at selected sites on New Jersey streams tributary to, and including the Delaware Bay 41 FACTORS FOR CONVERTING INCH-POUND UNITS TO INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM UNITS (SI) For those readers who may prefer to use the International System (SI) units rather than inch-pound units, the conversion factors for the terms used in this report are listed below: Multiply inch-pound unit By To obtain SI unit feet (ft) 0.3048 meters (m) miles (mi) 1 .609 kilometers (km) square miles 2.590 square kilometers (mi 2 ) (km 2 ) II ABSTRACT Drainage areas of New Jersey streams tributary to the Delaware River and Delaware Bay are listed for over 1,100 sites. -

Beyond the Exit

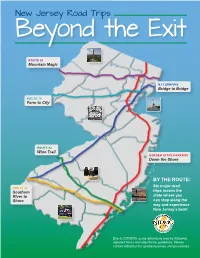

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

NEW JERSEYANNUAL REPORT JULY 1, 2018 – JUNE 30, 2019 WHERE WE WORK the Nature Conservancy 2019 PROJECTS in New Jersey

NEW JERSEYANNUAL REPORT JULY 1, 2018 – JUNE 30, 2019 WHERE WE WORK The Nature Conservancy 2019 PROJECTS in New Jersey BOARD OF TRUSTEES Paulins Kill Mark DeAngelis, Chair Valerie Montecalvo Watershed Anne H. Jacobson, Vice Chair Arnold Peinado Glenn Boyd Margaret Post Bobcat Hyper-Humus Alley High Mountain Warren Cooke David A. Robinson County Line Dam Susan Dunn Benjamin Rogers Paulina Dam New Bobcat Alley Acquisition Aaron Feiler Geraldine Smith Vanita Gangwal Dennis Toft Columbia TNC Chester Dam Oce R. Jay Gerken Lisa Welsh Point Amy Greene Jim Wright Mountain Musconetcong Highlands CONSERVANCY COUNCIL DEAR FRIENDS Thomas G. Lambrix Naval Weapons Anne H. Jacobson, Co-Chair Station Earle Dennis Hart, Co-Chair Bill Leavens With your help, our ambitious 2015 – 2020 conservation goals are in sight – and in a few cases achieved early! Barbara Okamoto Bach Ann B. Lesk Navesink River, Michael Bateman Hon. Frank LoBiondo Pennington Red Bank Mary W. Baum Robert Medina This year has seen some big conservation achievements, including the largest dam removal to date in the state of New Jersey. Our efforts to focus Mountain Susan Boyle Elizabeth K. Parker statewide protection of lands and waters on the highest-priority areas are gaining momentum. And, as always, we are planning for the future, Slade Dale Susan M. Coan John Post preparing to raise the bar on our conservation impact. Sanctuary, Carol Collier Kathy Schroeher Point Pleasant 2 Hans Dekker James A. Shissias Alma DeMetropolis Tracy Straka How can we have an even bigger conservation impact? Certainly, it will involve leveraging our strengths – our foundation in science, our Kate Tomlinson Robin Dougherty experience bringing together collaborative partnerships, and our track record of delivering tangible, lasting results.