Spar Caves As Fossil Hydrothermal Systems: Timing and Origin of Ore Deposits in the Delaware Basin and Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico and Texas, USA David D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/087 THIS PAGE: Calcite Rafts record former water levels at the Deep End a remote pool discovered in January 2009. ON THE COVER: On the Candlelight Tour Route in Wind Cave boxwork protrudes from the ceiling in the Council Chamber. NPS Photos: cover photo by Dan Austin, inside photo by Even Blackstock Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/087 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 March 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Group

MINERALS SORTED BY MINERAL GROUP Most minerals are chemically classified as native elements, sulfides, sulfates, oxides, silicates, carbonates, phosphates, halides, nitrates, tungstates, molybdates, arsenates, or vanadates. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). NATIVE ELEMENTS (DIAMOND, SULFUR, GOLD) Native elements are minerals composed of only one element, such as copper, sulfur, gold, silver, and diamond. They are not common in Kentucky, but are mentioned because of their appeal to collectors. DIAMOND Crystal system: isometric. Cleavage: perfect octahedral. Color: colorless, pale shades of yellow, orange, or blue. Hardness: 10. Specific gravity: 3.5. Uses: jewelry, saws, polishing equipment. Diamond, the hardest of any naturally formed mineral, is also highly refractive, causing light to be split into a spectrum of colors commonly called play of colors. Because of its high specific gravity, it is easily concentrated in alluvial gravels, where it can be mined. This is one of the main mining methods used in South Africa, where most of the world's diamonds originate. The source rock of diamonds is the igneous rock kimberlite, also referred to as diamond pipe. A nongem variety of diamond is called bort. Kentucky has kimberlites in Elliott County in eastern Kentucky and Crittenden and Livingston Counties in western Kentucky, but no diamonds have ever been discovered in or authenticated from these rocks. A diamond was found in Adair County, but it was determined to have been brought in from somewhere else. SULFUR Crystal system: orthorhombic. Fracture: uneven. Color: yellow. Hardness 1 to 2. -

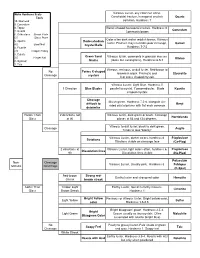

Mineral Flow Chart

Mohs Hardness Scale Vitreous Luster, any color can occur. Tools Conchoidal fracture, hexagonal crystals Quartz 10. Diamond common, Hardness 7 9. Corundum 8. Topaz Barrel shaped hexagonal crystals, Hardness 9, Corundum 7. Quartz Commonly brown 6. Orthoclase Streak Plate 5.5 Glass Plate Color often dark red or reddish brown. Vitreous 5. Apatite Dodecahedron luster. Fracture may resemble poor cleavage, Garnet 4.5 Steel Nail Crystal Balls 4. Fluorite Hardness 7-7.5 3.5 Copper Penny 3. Calcite Green Sand Vitreous luster, commonly in granular masses 2.5 Finger Nail Olivine 2. Gypsum Grains (looks like sand grains), Hardness 6.5-7 1. Talc Vitreous, resinous, or dull luster. Red-brown to No Forms X-shaped brownish-black. Prismatic and Staurolite Cleavage crystals X or cross shaped crystals Vitreous Luster, Light Blue. Hardness 5 1 Direction Blue Blades parallel to crystal, 7 perpendicular. Blade Kyanite shaped crystals Cleavage Bluish green. Hardness 7.5-8. Elongate six- difficult to Beryl sided crystal prisms with flat ends common determine Harder Than 2 directions not Vitreous luster, dark green or black. Cleavage Hornblende Glass at 90 planes at 56 and 124 degrees. Vitreous to dull luster, black to dark green. Cleavage Augite Tends to look "blocky" Vitreous Luster, darker colors, hardness 6. Plagioclase Striations Striations visible on cleavage face (Ca-Plag) 2 directions at Vitreous Luster, light colors often, hardness 6. Plagioclase Dissolution lines 90 Dissolution lines visible (Na-Plag) Potassium Non- Cleavage Vitreous Luster, Usually pink. Hardness 6. Feldspar Metallic Next Page (K-Spar) Red-brown Strong red- Earthy luster and strong red color Hematite Streak brown streak Softer Than Yellow/ Light Earthy Luster, found in earthy masses, Limonite Glass Brown Streak Hardness 1 Bright Yellow Resinous or vitreous luster. -

The Development of a Technology-Infused 5Th-8Th Grade Earth

THE DEVELOPMENT OF A TECHNOLOGY-INFUSED 5th -8th GRADE EARTH SCIENCE CURRICULUM FOCUSING ON CAVES CURRICULUM PROJECT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Education in Environmental Education in the College of Education and Human Services Professions By Noelle J. Grunwald, B.S. University of Minnesota Duluth October 2014 Curriculum Project Committee: Bruce H. Munson, Ph.D., Chair Julie Ernst, Ph.D. Terrie Shannon, Ph.D. ii Abstract Traditional interpretive and educational programs within the National Park Service, a bureau of the United States Department of the Interior, have been developed on the principle that when people interact firsthand with the tangible resources found within National Park Service (NPS) sites they come to understand the meanings, concepts, stories, and relationships pertaining to these places better. While a direct physical connection to America’s national parks is desired, it is not always feasible. As a result, the NPS has embraced the Internet and the World Wide Web as a valuable and effective tool to reach out and engage visitors, specifically those who may never set foot inside a park’s boundaries. Many sites within the national park system are adapting technology to enhance place-based learning in park settings and at a distance (USNPS, 2006). The purpose of this study was to address the current programming needs of the interpretation and education division staff at Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota by developing a curriculum that utilized the Internet and educational technology to reach out, engage and provide memorable and meaningful learning experiences regarding caves and karst topography to formal educators and their classrooms. -

Public Release of Subsurface Management Plan

Oregon Caves National Monument Subsurface Management Plan 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose and Significance........................................................................................ 4 B. Legislative and Administrative Requirements......................................................... 5 II. PRESENT RESOURCE STATUS............................................................................. 7 III. DATA COLLECTION A. Cave Classification………………………………………………………………... 12 B. Inventories…………………………………………………………………………. 12 IV. RESOURCE PROTECTION A. Visitor Use 1. Carrying Capacity……………………………………….……………………….12 2. Caving Permits…………………………………………………………………. 13 B. Interpretation 1. Publications............................................................................................ 15 2. Interpretive Tours................................................................................... 16 3. Outreach Programs................................................................................ 16 4. Audio-visual.......................................................................................... 16 5. Visitor Survey....................................................................................... 16 C. Ranger Patrols.......................................................................................................... 17 D. Cave Locations.................................. E. Gates......................................................................................................................... 18 F. Cave Alteration........................................................................................................ -

Caves Beautiful Rushmore Cave, Keystone Beautiful Wonderland Cave, Nemo Back Hills Caverns, Rapid City Crystal Cave Park, Rapid

Caves Beautiful Rushmore Cave, Keystone Beautiful Wonderland Cave, Nemo Back Hills Caverns, Rapid City Crystal Cave Park, Rapid City Jewel Cave National Monument, Custer- pay for tour only, no need for a national park pass Wind Cave National Park, Hot Springs- pay for tour only, no need for a national park pass Notice the list of commercial caves able to be visited. Circling the Black hills is a belt of limestone caves. Great tectonic forces caused magma to be pushed up, revealing the granite basement rocks. The limestone that encircles this granite is gently tipped. Jewel Cave National Monument with 142 miles of mapped passages is known for its calcite crystal formations of dogtooth spar and nailhead spar. Wind Cave National Park has 128 miles of passages with the rare crystal formations of boxwork. The other Black Hills caves offer other cave formations such as stalagmites, columns, flowstone, frostwork, and cave popcorn. Caves How are caves formed? Erosion does not happen only on the surface; it can happen underground too. Groundwater can erode rock, especially limestone resulting in caves. Once the cave is formed the decorating begins, dripping water from the ceiling may leave a deposit forming an icicle-like structure hanging down (stalactite). This water may drip down to the floor leaving a deposit and forming a stalagmite. When groundwater dissolves limestone, it must eventually redeposit it. Since cave formations are formed drop by drop, it is often assumed that it took million of years for these formations to form. However, in the basement of the Lincoln Memorial and other places there are both stalactites and stalagmites; these did not take millions of years to develop, just the right conditions. -

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Jewel Cave National Monument

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Jewel Cave National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/084 THIS PAGE: Flowstone and Spar ON THE COVER: Speleothems . The clearly visible faces of calcite crystals in Jewel Cave create a back- drop for stalactites, deposited by droplets of water rich in calcium carbonate. NPS Photos by: Cover photo by Art Palmer Jewel Cave National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/084 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 March 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

The Fluorspar Deposits of Hardin and Pope Counties, Illinois By

111 Hill Hill State Geological h» yfflra I I ,.":: i URBANA ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 3 3051 00000 1911 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/fluorspardeposit58bast STATE OF ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION DIVISION OF THE STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. M. LEIGHTON, Chief BULLETIN NO. 58 THE FLUORSPAR DEPOSITS OF HARDIN AND POPE COUNTIES, ILLINOIS BY EDSON S. BASTIN «XK?S25S PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE STATEIOF.ILLINOIS URBANA, ILLINOIS 1931 STATE OF ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION M. F. Walsh, Director BOARD OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND CONSERVATION M. F. Walsh, Chairman Edson S. Bastin, Geology Henry C. Cowles, Botany William A. Noyes, Chemistry Charles M. Thompson, Representing John W. Alvord, Engineering the President of the University of William Trelease, Biology Illinois STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISION M. M. Leighton, Chief Jeffersons Printing &. Stationery Co. Springfield, Illinois bs 7 CONTENTS Page Chapter I —Introduction 9 Location of district 9 Historical summary 10 Earlier geologic reports 11 Types of fluorspar deposits 12 Chapter II—Vein deposits 13 Distribution 13 Vein walls 13 Evidence of replacement 14 Ragged limestone remnants 16 Stylolitic structures 17 Diffusion banding 22 Summary 24 Minerals of the veins- 25 Fluorite 25 Calcite 25 Quartz 25 Galena 26 Sphalerite 27 Pyrite 29 Chalcopyrite 30 Barite 30 Gypsum 31 Cuprite and malachite 31 Relations between calcite and fluorite 31 Oil and bitumen in -

Geologic Walking Tour of Carlsbad Cavern Carol A

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/44 Geologic walking tour of Carlsbad Cavern Carol A. Hill, 1993, pp. 117-128 in: Carlsbad Region (New Mexico and West Texas), Love, D. W.; Hawley, J. W.; Kues, B. S.; Austin, G. S.; Lucas, S. G.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 44th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 357 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1993 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Geology and Origin of Mystery Cave TECHNICAL REPORT

Geology and Origin of Mystery Cave Fo~tville State Park, Minnesota TECHNICAL REPORT LC:MR Mystery Cave Resources Evaluation Arthur N. Palmer Margal'et V. Palmer 1993 This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) Consultant's Report ACKNOWLEDGMENT: Funding for this project was approved by the Minnesota Legislature M. L. 91, Chapter 254, Article 1, Section 14, Subd. 3(1), as recommended by the Legislative Commission on Minnesota Resources, from the Future Resources Fund. COPYRIGHT 1993 STATE OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES FORESTVILLE STATE PARK GEOLOGY AND ORIGIN OF MYSTERY CA VE Technical Report Arthur N. Palmer and Margaret V. Palmer Department of Earth Sciences State University of New York Oneonta, NY 13820-4015 page CONTENTS 2 Introduction 3 Geologic setting 3 Field and laboratory methods 3 Leveling survey 5 Accuracy of leveling survey 6 Computer analysis of survey data 7 Sampling of bedrock and speleothems 7 Stratigraphic mapping 8 Refraction seismology 11 Vibration study 13 Photography 13 Laboratory preparation of samples 13 Thin-section analysis 13 X-ray diffraction 14 Scanning electron microscopy and EDX analysis 14 Geochemistry 15 Geologic profile of Mystery Cave 16 Stratigraphic interpretation 16 Bedrock composition 19 Interpretation of environments of -

Fluorspar in New Mexico

New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY Fluorspar in New Mexico by William N. McAnulty SOCORRO 1978 iii Acknowledgments This report is the product of a study of all previously published works on fluorspar in New Mexico and evaluation of new data gathered over a period of six years (1970- 75) by the author and ten graduate students (working on M.S. theses under his direction) at University of Texas at El Paso. Also, a significant contribution was made by a graduate student at University of Western Ontario. Altogether, the results of eight M.S. theses on fluorspar in New Mexico are incorporated in this report. In addition to revising and supervising the theses, I examined all of the principal deposits in the state. This study was sponsored by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, and special thanks are due Dr. Frank E. Kottlowski, Director, for his support and encouragement in the initiation and execution of the project. Grants- in-aid were provided by New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources to the following graduate students at University of Texas at El Paso: Edward J. Huskinson for work in the Chise area, Sierra County; Robert C. Rogers, eastern Caballo Mountains, Sierra County; Martin A. Nelson, southern Caballo Mountains, Sierra County; Richard W. Morris, northern Cooke's Peak area, Grant County; Brad P. Biggerstaff, Steeple Rock-Twin Peaks area, Grant County; Randal I. Arnold, Little Whitewater-Holt Canyon area, Catron County; Harold M. Messenger, Zuni Mountains, Valencia County; and Thomas J. -

Optical Calcite Deposits in Park and Sweet Grass Counties, Montana

Optical Calcite Deposits in Park and Sweet Grass Counties, Montana GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1042-M Optical Calcite Deposits in Park and Sweet Grass Counties, Montana By W. C. STOLL and FRANK C. ARMSTRONG S CONTRIBUTIONS TO ECONOMIC GEOLOGY l GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1042-M A report on Montana deposits that pro vided essential optical material during the early years of ff^orld ffiar II UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1958 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Oifice Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Abstract_____________________________________________________ 431 Introduction... _______________________________________________ 432 History, mining, and production___________________________________ 434 Geology_______----__---_---_---_-___--__---_--------_---------_-- 444 Optical calcite deposits_____-________-___-____--__-_-_-___-_-_--___- 448 Mines and prospects_______________________________________________ 459 Wade and Killorn properties, sees. 7 and 8, T. 1 N., R. 9 E_____ _ 459 Wade property, SW% sec. 7, T. 1 N., R. 9 E________________ 464 Wade property, S^ sec. 6, T. 1 N., R. 9 E_________________ 465 Killorn property, N}'2 sec. 18, T. 1 N., R. 9 E.______________ 465 Gibson property.______________________________________________ 466 Francis property.___________________________________________ 466 Bodine mine__________________________________________________ 467 Miller