Master's Thesis Template Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Kenya

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KISUMU REPORT ON ESTABLISHMENT OF VILLAGE UNITS IN KISUMU COUNTY 2019 COMPILED BY THE COMMITTEE ON DELINEATION OF VILLAGE UNITS TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................1 Background ..............................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER TWO .......................................................................................................................................5 Submissions from the Ward per Sub - County .........................................................................................5 Kisumu East Sub – County...................................................................................................................5 Seme Sub – County ............................................................................................................................16 Kisumu Central Sub – County ............................................................................................................29 Nyakach Sub – County .......................................................................................................................46 -

Women Empowerment Through Training and Micro Enterprises Development in Kenya

Women Empowerment through Training and Micro Enterprises Development in Kenya 2017-2018 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 3 PROBLEMS AND JUSTIFICATION ............................................................................................ 4 NEEDS ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................................. 9 STAKEHOLDER IDENTIFICATION & ANALYSIS ............................................................... 11 1. Main Stakeholders .................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 2. Project’s Implementation ........................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. ABOUT THE PROJECT .............................................................................................................. 11 3. Objectives .............................................................................................................................. 13 a) Main objective .................................................................................................................... 13 b) Specific objectives .............................................................................................................. 13 Sustainability................................................................................................................................ -

Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan Ii, 2018-2022

KISUMU COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN II, 2018-2022 Vision: A peaceful and prosperous County where all citizens enjoy a high- quality life and a sense of belonging. Mission: To realize the full potential of devolution and meet the development aspirations of the people of Kisumu County i Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan | 2018 – 2022 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................... II LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................. VII LIST OF MAPS/FIGURES ................................................................................................... X LIST OF PLATES (CAPTIONED PHOTOS) .................................................................... XI ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... XIII FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................... XV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................ XVIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ XX CHAPTER ONE: .................................................................................................................... 1 COUNTY GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................... 1 -

Curriculum Vitae Henry Wangutusi Mutoro

CURRICULUM VITAE HENRY WANGUTUSI MUTORO DATE OF BIRTH : 22 January 1950 PLACE OF BIRTH: Bungoma District, Western Province. Kenya NATIONALITY : Kenyan MARITAL STATUS: Married with children DESIGNATION : Associate Professor HOME ADDRESS : P. O. Box 19808 Nairobi Mobile No. 0722-747612 OFFICE ADDRESS: Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Academic Affairs (Ag.) University of Nairobi P. O. Box 30197 – 00100 NAIROBI Tel. (20) 318262 Ext 28296 ; 28243 Fax 254 20 2245566 E-mail: [email protected] MANAGEMENT/ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE AND SELECTED COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP A) April 24, 2015 – DATE : Appointment as Chairman of the Management Joint Negotiations Committee Team on the 2013-2015 (Collective Bargaining Agreements) CBAs Units dealt with: Universities Academic Staff Union - UASU Kenya Universities Staff Union- KUSU Kenya Union of Domestic Hotels, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Union - KUDHEIHA B) July 15, 2013 – TO DATE: DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR, ACADEMIC AFFAIRS (DVC – AA), UON Major objectives: Improvement in University ranking. High quality graduates Enhancement of programmes to match industry Intensified enrolment into university education Prof H. W. Mutoro, June 19, 2015 Page 1 of 20 RESPONSIBILITIES Head of the Academic Division Chairman, Deans Committee Chairman, Senate Appeals Committee Chairman, Lectureship Appointments Committee Chairman, Senior Lectureships Appointments Committee Such other duties as may be assigned by the Vice-Chancellor C) MAY 15, 2013 – July 15, 2013: AG. DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR, ACADEMIC AFFAIRS -

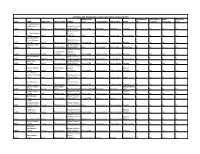

Approved and Operational Health Facilities in Kisumu County

APPROVED AND OPERATIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES IN KISUMU COUNTY REGULATORY OPEN WHOLE OPEN PUBLIC OPEN OPEN LATE CODE NAME KEPH LEVEL FACILITY TYPE OWNER BODY CONSTITUENCY SUB COUNTY WARD DAY HOLIDAYS WEEKENDS NIGHT Tumaini Kopere Health Care Private Practice - 25247 Services Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Muhoroni Muhoroni Chemelil No No No No Private Practice - St. Lucia Medical Nurse / 25071 Centre Level 3 Medical Center Midwifery None Kisumu East Kisumu East Kolwa Central Yes Yes Yes Yes Dalcoo Medical Centre(Kisumu Private Practice - 24971 Central) Level 3 Medical Center Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Kondele Yes Yes Yes Yes Angeline Health Private Practice - 24949 Care Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer None Kisumu East Kisumu East Manyatta B No No Yes No Private Practice - Primary care General 24940 Fairmont Hospital Level 4 hospitals Practitioner Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Railways Yes Yes Yes Yes Good Neighbour Private Practice - 24904 clinic Level 2 Medical Clinic Private Company Pharmacy & PoisonsKisumu Board West Kisumu West West Kisumu No No No Yes Danid Care Private Practice - 24880 Services Level 3 Nursing Homes Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Kondele Yes Yes Yes Yes Private Practice - Jobefar Medical Basic Health General Market 24824 Centre Level 3 Centre Practitioner Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Milimani Yes Yes Yes Yes Peter Plumb Harmony Medical Private Practice - 24817 Clinic Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer None -

Prevalence of Depression Among Active TB and TB/HIV Patients in Kisumu County Esther Lee SIT Graduate Institute - Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2015 Prevalence of Depression among Active TB and TB/HIV Patients in Kisumu County Esther Lee SIT Graduate Institute - Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Immune System Diseases Commons, Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Esther, "Prevalence of Depression among Active TB and TB/HIV Patients in Kisumu County" (2015). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2152. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2152 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PREVALENCE OF DEPRESSION AMONG ACTIVE TB AND TB/HIV PATIENTS IN KISUMU COUNTY Esther Lee SIT Fall 2015 Wellesley College 1 ABSTRACT According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in four people have been affected by a mental health disorder at one point in their lives.1 Kenya’s mental disorders account for 5.9% of the total global burden.2 Mental disorders like depression is often comorbid with TB and HIV and disproportionately affects those with lower socio-economic income. Kisumu, a city in Nyanza province, has the highest HIV and TB prevalence in Kenya. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of depression among TB non-coinfected and TB/HIV co-infected patients at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH) and the Clinical Research Center (CRC) in Kisumu County. -

ANNEX I: References Brookings Institute. 2013. Top Five Reasons Why Africa Should Be a Priority for the United States

ANNEX I: References Brookings Institute. 2013. Top Five Reasons Why Africa Should Be a Priority for the United States; Africa Growth Initiative. Washington, D.C. March 2013. http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2013/04/africa-priority-united-states Bureau of African Affairs. 2013. Joint Regional Strategy FY 2015-2017. February 7, 2013. DAI. 2012. Rapid Political Economy Assessment; Drivers of Accountability Programme; September 2012. Development and Training Services. Inc. (DTS). 2012. Arid and Marginal Lands Recovery Consortium (ARC) Program in Kenya: Final Evaluation. For USAID/Kenya. October 12, 2012. Development and Training Services. Inc. (DTS). 2012. Mid-term Evaluation of USAID/Kenya Natural Resource Management Projects. For USAID/Kenya. April 2, 2012. Development and Training Services. Inc. (DTS). 2012. Multi-Stakeholder Evaluation of Agriculture and Livestock Value Chain Activities in Kenya. For USAID/Kenya. March 29, 2012. Department for International Development (DFID). 2004. Strengthening the Incentives for Pro- Poor Policy Change: An analysis of drivers of change in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya 2004. Eberhard et al. 2008.Underpowered: The State of the Power Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. Background Paper 6. Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic, World Bank, Washington, D.C. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2005. Forest Resources Assessment. http://www.fao.org/forestry/fra/fra2005/en/. Foster, Vivien and Briceño-Garmendia Cecilia (editors). 2010. Africa’s Infrastructure: A Time for Transformation. African Development Bank and the World Bank, Washington D.C. https://www.infrastructureafrica.org/library/doc/552/africa%E2%80%99s-infrastructure-time- transformation. Government of Kenya. 2012. Facts and Figures, Basic Education Bill 2012. Nairobi, Kenya. Government of Kenya. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE MERCY MUTHONI MUGAMBI University of Nairobi P.O Box 92 – 00902 Kikuyu, Kenya School of Education Cell phone: 0725600046 Department of Educational Email: [email protected] Administration and planning Date of birth MAY 6TH 1962 CURRENT POSITION Lecturer: Department of Educational Administration and planning, School of Education; and part-time lecturer College of Education and External Studies. Memberships: School Board of Examiners, Departmental timetabling committee, Assistant examination officer Education Background 2008- 2012: Doctor of Philosophy in Education: Catholic University of Eastern Africa (CUEA). Title: Analysis of Factors Influencing the Implementation of Secondary School Life Skills curriculum in Secondary schools in Kajiado County, Kenya. Supervisors: Prof. J. Malusu and Dr. A. Kiflemariam. 2004-2006: Master of Education; University of Nairobi (UON) –Kenya (Specialization Curriculum Studies). 1985- 1988: Bachelors of Education (Home Economics); Kenyatta University areas of studies – Education, Physical Education, and Kiswahili Language; Qualification – Second Class Honours Upper Division. 1982- 1884: Kenya Advanced Certificate of Education, Kangaru School, Embu 1978- 1981: Kenya Certificate of Secondary School Education (KCSE); Muthambi Girls’ Secondary School –Meru 1971- 1977: Certificate of Primary School (CPE); St Usura Primary School – Embu District DUTIES a) Academic Teaching TAP 614: Curriculum Designing and Development (Doctor of Education- UoN). TAP 505: Curriculum Theory and Practice (Master of education-UoN)Evaluation rating TAP 511: Curriculum Design (Master of education-UoN). Evaluation rating TAP 201: Curriculum Development (BED-UoN). Evaluation rating TAP 402: Teacher Education (BED-UoN) Evaluation rating LDP 604: Project planning, designing and implementation (MA Project planning and Management – UoN) 1 LDP 606: Training and Curriculum Development (MA Project planning and management –UoN) LPM 315 Training and development (BA Project planning and management – UoN). -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CRIME ANDVIOLENCERAPIDASSESSMENT KISUMU COUNTY KISUMU COUNTY CRIME AND VIOLENCE RAPID ASSESSMENT Cover photo: Kit-Mikayi, a natural rock formation and UNESCO World Heritage cultural site, is located about 29 kilometers west of the city of Kisumu. Credit: Ministry of Tourism, County Government of Kisumu. Design and copy editing: Laura C. Johnson Contents Foreword .................................................v Acknowledgements .........................................vi Acronyms ................................................vii 1 Introduction .............................................1 Crime and Violence Prevention in Kenya ...............................3 Crime and Violence Prevention Training ...............................4 County-Level Crime and Violence Prevention ..........................5 Framework for Analysis .............................................7 Goals of the Rapid Assessment ......................................9 Methodology . .10 2. Background: Crime and Violence Trends in Kenya .............13 Boda-Boda-Related Crime and Violence .............................14 Alcohol and Drug Abuse ...........................................14 Sexual and Gender-Based Violence ..................................16 Violence against Children ..........................................16 Radicalization and Recruitment into Violent Extremism ..................17 3. Rapid Assessment of Kisumu County .......................19 -

Kisumu County Conflict Analysis

briefing Kisumu County conflict analysis Introduction complex political and social dynamics that are Kisumu is mostly an ethnically homogenous county affecting the lives of the people in Kisumu County. that is for the most part calm with flares of politically motivated violence especially during periods leading The assessment found that devolution has had some up to and after elections. The large numbers of positive impacts, particularly in relation to unemployed youth, especially in the city, are often infrastructure projects, improvements to health used by politicians, who through these youth use services, and agricultural support. The county’s violence to instil fear in their rivals. The County has commitment to increased representation and also experienced an increase in tensions and participation in governance by traditionally consequently violent conflict along the Nyakach/Nandi marginalised groups, including women and people border and Muhoroni due to cattle rustling and living with disabilities, was also positively received by boundary-related disputes, and a mixture of inter- those interviewed during the assessment, with community rivalry between the Nandi and Luo as well several County Assembly Committees headed by as land issues.1 2007 witnessed a cessation of women and representation by people living with violence between the two communities, which were disabilities serving on the Public Service Board. perceived to have a common political interest in the Despite these positive steps, there remain Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) winning the fundamental challenges in the management of county elections. This changed with the subsequent fallout business. The majority of those consulted felt their between Raila Odinga and William Ruto. -

KISUMU County Urban Institutional Development Strategy (CUIDS) Kisumu City

COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KISUMU County Urban Institutional Development Strategy (CUIDS) Kisumu City COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KISUMU Page 1 SECTION 1: URBANIZATION, URBAN MANAGEMENT &URBAN DEVELOPMENT IN THE COUNTY 1.1. Urbanization, urban development and urbanization trends in the county Kisumu County lies between longitudes 33o 20’E and 35o 20’E and latitude 00o 20’ South and 00o 50’ South. The County is bordered by Homa Bay County to the South, Nandi County to the North East, Kericho County to the East, Vihiga County to the North West, Siaya County to the West and is surrounded by the second largest freshwater lake in the World-Lake Victoria. Kisumu County covers approximately 567 km2 on water and 2,086km2 land area, representing 0.36% of the total land area of Kenya's 580,367km2. The population is estimated at 1,224,531 persons as at the start of the plan period 2018. The county’s urbanization revolves around the City of Kisumu and the satellite high population areas that are scattered in different parts of the county. Kisumu City is the major high density and high population urban area in the county. The City covers Kisumu Central, Kisumu East, and parts of Kisumu West constituencies/Sub-Counties. The proportion of those residing in urban areas within the county account for 50.30 percent of the total population. 40 percent of these urban dwellers reside in the informal settlements within the city including:Nyalenda “A” and “B”; Manyatta “A” and “B” and Obunga. The land tenure system within these informal settlements is free-hold. -

Special Interruption Notice

POWER INTERRUPTION NOTICE Kenya Power will interrupt electricity power supply on Saturday 12th July 2014 and Sunday 13th July, 2014 to parts of Kisumu County and Central Business District as detailed below. We request our customers in these areas to bear with us as we upgrade the system in order to improve the quality of our services. The Company regrets any inconvenience that may be caused during the operation. AREA: KONDELE, KISUMU TOWN, MILIMANI, DUNGA, NYALENDA, KIBOS, MASENO DATE: Saturday 12.07.2014 TIME: 6.00 A.M. - 7.00 P.M. Nyahera, Kima, Kiboswa, Kisian, Ober Kamoth Kondele Mkt, Manyatta Area, Car Wash Area, Steel Mill, Kibos Mkt, Chiga Mkt, Kasese Mkt, Great Lake University, Gita Mkt, Got Nyabondo Area, Kenya-Re Estate, Swan Centre, Electricity House, Jua Kali, Kamas, Agha Khan Hall, Oil Libya, Nakumatt Nyanza, Ukwala Supermarket, Co-operative Bank, National Bank, Standard Chartred Bank, Nyalenda Estate, Kiboko Bay, Impala Park, Dunga Beach, Tom Mboya Labour College, Whole of Milimani Estate, Central Bank, Kenya Commercial Bank, Kisumu Hotel, Imperial Hotel, Check Mula Building, Winam Chemist, Kisumu District Hospital, Shajanand Quarry, Ujenzi Quarry, Ober Kamoth Health Center, Kaloka Beach, Obambo Secondary School, Royal Media Kiboswa, Nyahera, Alara, Rock Motel, Chulaimbo, Daraja Mbili, Holo, Obambo, Kisian, Tieng’re, Otonglo, Kodiaga Men & Women Prisons, KEMRI Kisian, Riat, Kanyamedha, Parts of Luanda, Maseno University, Maseno School, Maseno Mkt, Maseno Law Courts, Bunyore Girls, Ibubi Girls, Emuhaya, Emusire, Ebutsiratsi, Mudavadi Girls, Madzuu, Mahanga, Chevavo, Ebunangwe & adjacent customers. AREA: PARTS OF KISUMU TOWN, SABUNI ROAD, KANO, MANYATTA DATE: Sunday 13.07.2014 TIME: 6.00 A.M.