World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case of Twitter Data in Kenya

A FRAMEWORK FOR PROFILING CRIME REPORTED USING SOCIAL MEDIA – A CASE OF TWITTER DATA IN KENYA BY GIDEON K. SUMBEIYWO A Project Report Submitted to the School of Science and Technology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Science in Information Systems and Technology UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY – AFRICA SUMMER 2018 1 STUDENT’S DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that this is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college, institution or university other than the United States International University – Africa in Nairobi for academic credit. Signed: ________________________ Date: _________________ Gideon Kipkorir Sumbeiywo (ID No 620128) This project has been presented for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor. Signed: ________________________ Date: _________________ Dr. Leah Mutanu Signed: ________________________ Date: _________________ Dean, School of Science and Technology 2 COPYRIGHT All rights reserved; No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without express written authorization from the writer. Gideon Kipkorir Sumbeiywo © 2018 3 ABSTRACT Crime profiling helps law enforcement agencies understand, tackle and sometimes predict the next move by criminals. This can be achieved by monitoring and studying patterns and trends that have occurred in the past and continue to occur in the present. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Google Plus, Instagram, Reddit and in this case Twitter, have created platforms where people share views, opinions and emotions all the while influencing and informing others. This research set out with four objectives that would enable it to be successful in coming up with a framework for profiling. -

Republic of Kenya

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KISUMU REPORT ON ESTABLISHMENT OF VILLAGE UNITS IN KISUMU COUNTY 2019 COMPILED BY THE COMMITTEE ON DELINEATION OF VILLAGE UNITS TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................1 Background ..............................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER TWO .......................................................................................................................................5 Submissions from the Ward per Sub - County .........................................................................................5 Kisumu East Sub – County...................................................................................................................5 Seme Sub – County ............................................................................................................................16 Kisumu Central Sub – County ............................................................................................................29 Nyakach Sub – County .......................................................................................................................46 -

Mombasa County Crime and Violence Report

MOMBASA COUNTY CRIME AND VIOLENCE RAPID ASSESSMENT MOMBASA COUNTY CRIME AND VIOLENCE RAPID ASSESSMENT Cover photo credit: Andrea Albini | Creative Commons 3.0 Design and copy editing: Laura C. Johnson II Contents Foreword .................................................v Acknowledgements .........................................vi Acronyms ................................................vii 1 Introduction .............................................1 Crime and Violence Prevention in Kenya ...............................3 Crime and Violence Prevention Training ...............................4 County-Level Crime and Violence Prevention ..........................4 Framework for Analysis .............................................7 Goals of the Rapid Assessment ......................................9 Methodology . .9 2 Background: Crime and Violence Trends in Kenya ............13 Boda-Boda-Related Crime and Violence .............................14 Alcohol and Drug Abuse ...........................................14 Sexual and Gender-Based Violence ..................................16 Violence against Children ..........................................16 Radicalization and Recruitment into Violent Extremism ..................17 3 Rapid Assessment of Mombasa County .....................19 Overview of County ...............................................19 Cross-Cutting Drivers of Crime and Violence ..........................20 Dynamics of Crime and Violence ....................................23 Security Interventions .............................................40 -

Women Empowerment Through Training and Micro Enterprises Development in Kenya

Women Empowerment through Training and Micro Enterprises Development in Kenya 2017-2018 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 3 PROBLEMS AND JUSTIFICATION ............................................................................................ 4 NEEDS ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................................. 9 STAKEHOLDER IDENTIFICATION & ANALYSIS ............................................................... 11 1. Main Stakeholders .................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 2. Project’s Implementation ........................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. ABOUT THE PROJECT .............................................................................................................. 11 3. Objectives .............................................................................................................................. 13 a) Main objective .................................................................................................................... 13 b) Specific objectives .............................................................................................................. 13 Sustainability................................................................................................................................ -

Countering Wildlife Trafficking Through Kenya’S Seaports a Rapid Seizure Analysis

February 2020 COUNTERING WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING THROUGH KENYA’S SEAPORTS A RAPID SEIZURE ANALYSIS Willow Outhwaite Leanne Little JOINT REPORT Countering wildlife trafficking in KENYA’S SEAPORTS TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Reproduction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. This report was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Wildlife Trafficking Response, Assessment, and Priority Setting (Wildlife TRAPS) project implemented by TRAFFIC in collaboration with IUCN, and the UNDP-GEF Project “Reducing Maritime Trafficking of Wildlife between Africa and Asia” as part of the GEF-financed, World Bank-led Global Wildlife Program. The contents are the responsibility of TRAFFIC and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID, the U.S. Government or UNDP. Published by: TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, United Kingdom. © TRAFFIC 2020. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN no: 978-1-911646-20-4 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Design by Marcus Cornthwaite 2 TRAFFIC REPORT : COUNTERING WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING THROUGH KENYA’S SEAPORTS table of contents page 1 INTRODUCTION Executive summary Introduction Workshop objectives page 2 FRAMING THE ISSUE Kenya’s Wildlife Wildlife Trafficking and the Transport Sector Infrastructure -

Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan Ii, 2018-2022

KISUMU COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN II, 2018-2022 Vision: A peaceful and prosperous County where all citizens enjoy a high- quality life and a sense of belonging. Mission: To realize the full potential of devolution and meet the development aspirations of the people of Kisumu County i Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan | 2018 – 2022 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................... II LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................. VII LIST OF MAPS/FIGURES ................................................................................................... X LIST OF PLATES (CAPTIONED PHOTOS) .................................................................... XI ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... XIII FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................... XV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................ XVIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ XX CHAPTER ONE: .................................................................................................................... 1 COUNTY GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................... 1 -

Curriculum Vitae Henry Wangutusi Mutoro

CURRICULUM VITAE HENRY WANGUTUSI MUTORO DATE OF BIRTH : 22 January 1950 PLACE OF BIRTH: Bungoma District, Western Province. Kenya NATIONALITY : Kenyan MARITAL STATUS: Married with children DESIGNATION : Associate Professor HOME ADDRESS : P. O. Box 19808 Nairobi Mobile No. 0722-747612 OFFICE ADDRESS: Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Academic Affairs (Ag.) University of Nairobi P. O. Box 30197 – 00100 NAIROBI Tel. (20) 318262 Ext 28296 ; 28243 Fax 254 20 2245566 E-mail: [email protected] MANAGEMENT/ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE AND SELECTED COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP A) April 24, 2015 – DATE : Appointment as Chairman of the Management Joint Negotiations Committee Team on the 2013-2015 (Collective Bargaining Agreements) CBAs Units dealt with: Universities Academic Staff Union - UASU Kenya Universities Staff Union- KUSU Kenya Union of Domestic Hotels, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Union - KUDHEIHA B) July 15, 2013 – TO DATE: DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR, ACADEMIC AFFAIRS (DVC – AA), UON Major objectives: Improvement in University ranking. High quality graduates Enhancement of programmes to match industry Intensified enrolment into university education Prof H. W. Mutoro, June 19, 2015 Page 1 of 20 RESPONSIBILITIES Head of the Academic Division Chairman, Deans Committee Chairman, Senate Appeals Committee Chairman, Lectureship Appointments Committee Chairman, Senior Lectureships Appointments Committee Such other duties as may be assigned by the Vice-Chancellor C) MAY 15, 2013 – July 15, 2013: AG. DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR, ACADEMIC AFFAIRS -

Approved and Operational Health Facilities in Kisumu County

APPROVED AND OPERATIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES IN KISUMU COUNTY REGULATORY OPEN WHOLE OPEN PUBLIC OPEN OPEN LATE CODE NAME KEPH LEVEL FACILITY TYPE OWNER BODY CONSTITUENCY SUB COUNTY WARD DAY HOLIDAYS WEEKENDS NIGHT Tumaini Kopere Health Care Private Practice - 25247 Services Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Muhoroni Muhoroni Chemelil No No No No Private Practice - St. Lucia Medical Nurse / 25071 Centre Level 3 Medical Center Midwifery None Kisumu East Kisumu East Kolwa Central Yes Yes Yes Yes Dalcoo Medical Centre(Kisumu Private Practice - 24971 Central) Level 3 Medical Center Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Kondele Yes Yes Yes Yes Angeline Health Private Practice - 24949 Care Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer None Kisumu East Kisumu East Manyatta B No No Yes No Private Practice - Primary care General 24940 Fairmont Hospital Level 4 hospitals Practitioner Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Railways Yes Yes Yes Yes Good Neighbour Private Practice - 24904 clinic Level 2 Medical Clinic Private Company Pharmacy & PoisonsKisumu Board West Kisumu West West Kisumu No No No Yes Danid Care Private Practice - 24880 Services Level 3 Nursing Homes Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Kondele Yes Yes Yes Yes Private Practice - Jobefar Medical Basic Health General Market 24824 Centre Level 3 Centre Practitioner Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Milimani Yes Yes Yes Yes Peter Plumb Harmony Medical Private Practice - 24817 Clinic Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer None -

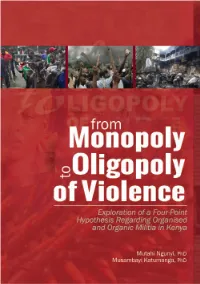

From Monopoly to Oligopoly of Violence

from Monopoly to Oligopoly of Violence i from Monopoly to Oligopoly of Violence From Monopoly to Oligopoly of Violence Exploration of a Four-Point Hypothesis Regarding Organised and Organic Militia in Kenya Mutahi Ngunyi, PhD Musambayi Katumanga, PhD i from Monopoly to Oligopoly of Violence From Monopoly to Oligopoly: Exploration of a Four-Point Hypothesis Regarding Organized and Organic Militia in Kenya Copyright © 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law. Disclaimer: All material contained reflects the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNDP or of the United Nations, or of the Government of Kenya. Published by: UNDP ISBN 978-9966-078-445 ii from Monopoly to Oligopoly of Violence DEDICATION; Dedicated to the memory of Prof. George Saitoti former minister for Internal Security under whose watch this study was commissioned. iii from Monopoly to Oligopoly of Violence ACKNOWLEDGEMENT On behalf of the authors, editors and all those involved, the UNDP Kenya and the National Steering Committee on Peace Building and Conflict Management (NSC), we would like to acknowledge the valuable inputs of the former Ministry of State for Provincial Administration and Internal Security under the leadership of the late Minister, Hon. (Prof.) George Saitoti, the Permanent Secretaries Mr. Francis T. -

The ICC Trial of Kenya's Deputy President

The ICC Trial of Kenya’s Deputy President Questions and Answers September 2013 1. What is the case against Ruto and Sang about? What crimes are they charged with? William Ruto and Joshua arap Sang are charged with the crimes against humanity of murder, forcible transfer of population or deportation, and persecution, stemming from their alleged involvement in an attack on perceived supporters of former President Mwai Kibaki’s Party of National Unity (PNU). According to the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecution, perpetrators destroyed houses and businesses identified as belonging to members of Kikuyu, Kamba, and Kisii ethnic groups thought to be PNU supporters, killing over two hundred people and injuring over a thousand more and forcing hundreds of thousands to flee. Five specific incidents occurring between late December 2007 and mid-January 2008 in Kenya’s Rift Valley form the basis for the charges. The prosecutor contends that Ruto along with others, and supported by Sang, worked for up to a year before the election to create a network to carry out the plan, and that this network was activated when the election results in favor of Kibaki were announced. The goals of the plan, the prosecutor alleges, were to punish and expel from the Rift Valley people perceived to support the PNU, and to gain power in the province. Ruto at the time was a member of parliament and a senior member of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), the party of Kibaki’s principal challenger, Raila Odinga. Sang was a radio host on the Eldoret-based Kass FM. -

Wildlife Protection and Trafficking Assessment in Kenya: Drivers And

WILDLIFE PROTECTION AND REPORT TRAFFICKING ASSESSMENT IN KENYA Drivers and trends of transnational wildlife crime in Kenya and LWVUROHDVDWUDQVLWSRLQWIRUWUDIÀFNHGVSHFLHVLQ(DVW$IULFD MAY 2016 Sam Weru TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. This publication was made possible through the support provided by the Office of Forestry and Biodiversity, Bureau for Economic Growth, Education and Environment, U.S. Agency for International Development, under the terms of award number AID-AID-EGEE-IO-13-00002. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Agency for International Development. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC, David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK. © TRAFFIC 2016. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN no: 978-1-85850-386-8 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Suggested citation: Weru, S. (2016). Wildlife protection and trafficking assessment in Kenya: Drivers and trends of transnational wildlife crime in Kenya and its role as a transit point for trafficked species in East Africa. -

BLOOD MONEY Financial Investigations Into Wildlife Crime in East Africa

POLITICAL ECONOMY ANALYSIS TRACKING BLOOD MONEY Financial investigations into wildlife crime in East Africa AMANDA GORE SEPTEMBER 2021 TRACKING BLOOD MONEY Financial investigations into wildlife crime in East Africa ww Amanda Gore September 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research for this report has relied heavily on a number of court documents in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, complemented by a review of media articles and other investigative reports. We also express our gratitude to officials and experts who granted interviews to include in the final report. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Amanda Gore is a forensic accountant with over 20 years’ experience supporting multi-jurisdictional financial investigations, specializing in anti- corruption, money laundering, tax and asset tracing. Gore runs the Centre for Global Advancement, which focuses on alternative legal and financial crime strategies to combat environmental crime. She is also researching underground payment systems and laundering techniques used by criminal groups. She leads graduate courses in wildlife crime and environmental crime in the Criminal Justice and Forensic Science Department of Investigations at the University of New Haven. Over the last five years, Gore has concentrated on applying financial-crime tools to environmental-crime offences, primarily in Africa, Asia and Latin America. © 2021 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing