Participatory Informal Settlement Upgrading and Well-Being in Kisumu, Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’S 2017 Elections

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH “Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34761 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa is an independent not-for profit organization that promotes freedom of expression and access to information as a fundamental human right as well as an empowerment right. ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa was registered in Kenya in 2007 as an affiliate of ARTICLE 19 international. ARTICLE 19 Eastern African has over the past 10 years implemented projects that included policy and legislative advocacy on media and access to information laws and review of public service media policies and regulations. The organization has also implemented capacity building programmes for journalists on safety and protection and for a select civil society organisation to engage with United Nations (UN) and African Union (AU) mechanisms in 14 countries in Eastern Africa. -

469880Esw0whit10cities0rep

Report No. 46988 Public Disclosure Authorized &,7,(62)+23(" GOVERNANCE, ECONOMIC AND HUMAN CHALLENGES OF KENYA’S FIVE LARGEST CITIES Public Disclosure Authorized December 2008 Water and Urban Unit 1 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank __________________________ This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without written authorization from the World Bank. ii PREFACE The objective of this sector work is to fill existing gaps in the knowledge of Kenya’s five largest cities, to provide data and analysis that will help inform the evolving urban agenda in Kenya, and to provide inputs into the preparation of the Kenya Municipal Program (KMP). This overview report is first report among a set of six reports comprising of the overview report and five city-specific reports for Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, Nakuru and Eldoret. The study was undertaken by a team comprising of Balakrishnan Menon Parameswaran (Team Leader, World Bank); James Mutero (Consultant Team Leader), Simon Macharia, Margaret Ng’ayu, Makheti Barasa and Susan Kagondu (Consultants). Matthew Glasser, Sumila Gulyani, James Karuiru, Carolyn Winter, Zara Inga Sarzin and Judy Baker (World Bank) provided support and feedback during the entire course of work. The work was undertaken collaboratively with UN Habitat, represented by David Kithkaye and Kerstin Sommers in Nairobi. The team worked under the guidance of Colin Bruce (Country Director, Kenya) and Jamie Biderman (Sector Manager, AFTU1). The team also wishes to thank Abha Joshi-Ghani (Sector Manager, FEU-Urban), Junaid Kamal Ahmad (Sector Manager, SASDU), Mila Freire (Sr. -

2020 Graduation Booklet

Virtual 14TH GRADUATION CEREMONY FOR THE CONFERMENT OF DEGREES, AND AWARD OF DIPLOMAS AND CERTIFICATES AT PINECONE HOTEL, KISUMU CITY Message from the Chancellor: PROF. NICK .G. WANJOHI – PHD(UoN), MA(CI), BA(HON), EBS, CBS . The Guest of Honour . Chairman of the Board of Trustees, . Chairperson of Council, . Vice Chancellor of the Great Lakes University of Kisumu, . Members of University Senate and Management Board, . Academic and Administrative staff, . Alumni and current Students, . All protocols observed. Distinguished guests, . Ladies and Gentlemen: I am extremely pleased and honoured to preside over this 14THGraduation Ceremony of the Great Lakes University of Kisumu. Every year, GLUK produces hundreds of graduates who have been well prepared to take up strategic roles in the development of themselves, their families, their communities in Kenya and the world at large. As the University Chancellor, I congratulate the graduands receiving Certificates, Diplomas, Bachelors, Masters, and Doctoral Degrees today for their academic achievements; a major milestone in your lives. Not many have been fortunate enough to make it this far for various reasons. It is therefore an event for you to cherish. The Degrees conferred and Certificates and Diplomas being awarded to you today are foundations on which to build your future. I encourage you to progress further in your academic pursuits so as to gain new knowledge, acquire advanced skills and new critical capabilities that will make you be more competitive nationally and globally. As I salute the graduands, I also pay special tribute to the University academic staff, who have prepared our students during their stay here. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Republic of Kenya

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KISUMU REPORT ON ESTABLISHMENT OF VILLAGE UNITS IN KISUMU COUNTY 2019 COMPILED BY THE COMMITTEE ON DELINEATION OF VILLAGE UNITS TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................1 Background ..............................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER TWO .......................................................................................................................................5 Submissions from the Ward per Sub - County .........................................................................................5 Kisumu East Sub – County...................................................................................................................5 Seme Sub – County ............................................................................................................................16 Kisumu Central Sub – County ............................................................................................................29 Nyakach Sub – County .......................................................................................................................46 -

CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: KENYA Last Update: 29 April 2010

WO RLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Global Task Force on Cholera Control CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: KENYA Last update: 29 April 2010 General Country Information: The Republic of Kenya is located in eastern Africa, and borders Ethiopia, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda and Sudan with an east coast along the Indian Ocean. Kenya is divided into eight provinces: Central, Coast, Eastern, North Eastern, Nyanza, Rift Valley and Western and Nairobi. The provinces are further subdivided into 69 districts. Nairobi, the capital, is the largest city of Kenya. In 1885, Kenya was made a German protectorate over the Sultan of Zanzibar and coastal areas were progressively taken over by British establishments especially in the costal areas. Hostilities between German military forces and British troops (supported by Indian Army troops) were to end in 1918 as the Armistice of the first World War was signed. Kenya gained its independence from Great Britain in December 1963 when a government was formed by Jomo Kenyatta head of the KANU party (Kenya National African Union). Kenya's economy is highly dependant on tourism and Nairobi is the primary communication and financial hub of East Africa. It enjoys the region's best transportation linkages, communications infrastructure, and trained personnel. Many foreign firms maintain regional branches or representative offices in the city. Since December 2007, following the national elections, Kenya has been affected by political turmoil and violent rampages in several parts of the country leading to economic and humanitarian crisis. Kenya's Human Development Index is 147 over 182. The major cause of mortality and morbidity is malaria. Malnutrition rates are high (around 50'000 malnourished children and women in 27 affected districts in 2006). -

Milka Awuor Ogayo Mail Address: 190-50100, Kakamega, Kenya

CURRICULUM VITAE ADDRESS AND PERSONAL DETAILS Name: Milka Awuor Ogayo Mail address: 190-50100, Kakamega, Kenya Email address: [email protected]/[email protected] Marital status: Married PROFESSIONAL SUMMARY In addition to my teaching career in the University, I am a goal oriented professional with over nine (9) years work experience as Deputy Director Nursing and Quality coordinator in a high volume hospital of Western Kenya. My ability to multitask, manage multitude of activities with a level of serene professionalism and sovereignty makes me a genuine and dependable employee. Moreover, my leadership skills and strong ability to analyze situations and produce high quality reports makes me outstanding team member. Furthermore, my excellent communication and negotiation skills with team members, and fellow staff have made me a reliable employee with strong personality radiating authority, professionalism and who is capable of adapting to various working conditions. My innovative skills have made enabled me to come up with varied change ideas and take on quality improvements activities while applying statistical knowlege to analyze data and demonstrate the magnitutde of change. SKILLS: • Computer skills • Writing skills • Data analysis • Communication • Leadership skills • Negotiation skills • Proposal Writing CURRENT EMPLOYMENT AND POSITIONS PREVIOUSLY HELD March 2020 to Date: Tutorial Fellow, Department of Nursing Research, Education and Management, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology 2018-2019: Part time teaching, Jaramogi -

Women Empowerment Through Training and Micro Enterprises Development in Kenya

Women Empowerment through Training and Micro Enterprises Development in Kenya 2017-2018 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 3 PROBLEMS AND JUSTIFICATION ............................................................................................ 4 NEEDS ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................................. 9 STAKEHOLDER IDENTIFICATION & ANALYSIS ............................................................... 11 1. Main Stakeholders .................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 2. Project’s Implementation ........................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. ABOUT THE PROJECT .............................................................................................................. 11 3. Objectives .............................................................................................................................. 13 a) Main objective .................................................................................................................... 13 b) Specific objectives .............................................................................................................. 13 Sustainability................................................................................................................................ -

Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan Ii, 2018-2022

KISUMU COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN II, 2018-2022 Vision: A peaceful and prosperous County where all citizens enjoy a high- quality life and a sense of belonging. Mission: To realize the full potential of devolution and meet the development aspirations of the people of Kisumu County i Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan | 2018 – 2022 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................... II LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................. VII LIST OF MAPS/FIGURES ................................................................................................... X LIST OF PLATES (CAPTIONED PHOTOS) .................................................................... XI ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... XIII FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................... XV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................ XVIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ XX CHAPTER ONE: .................................................................................................................... 1 COUNTY GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................... 1 -

Curriculum Vitae Henry Wangutusi Mutoro

CURRICULUM VITAE HENRY WANGUTUSI MUTORO DATE OF BIRTH : 22 January 1950 PLACE OF BIRTH: Bungoma District, Western Province. Kenya NATIONALITY : Kenyan MARITAL STATUS: Married with children DESIGNATION : Associate Professor HOME ADDRESS : P. O. Box 19808 Nairobi Mobile No. 0722-747612 OFFICE ADDRESS: Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Academic Affairs (Ag.) University of Nairobi P. O. Box 30197 – 00100 NAIROBI Tel. (20) 318262 Ext 28296 ; 28243 Fax 254 20 2245566 E-mail: [email protected] MANAGEMENT/ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE AND SELECTED COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP A) April 24, 2015 – DATE : Appointment as Chairman of the Management Joint Negotiations Committee Team on the 2013-2015 (Collective Bargaining Agreements) CBAs Units dealt with: Universities Academic Staff Union - UASU Kenya Universities Staff Union- KUSU Kenya Union of Domestic Hotels, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Union - KUDHEIHA B) July 15, 2013 – TO DATE: DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR, ACADEMIC AFFAIRS (DVC – AA), UON Major objectives: Improvement in University ranking. High quality graduates Enhancement of programmes to match industry Intensified enrolment into university education Prof H. W. Mutoro, June 19, 2015 Page 1 of 20 RESPONSIBILITIES Head of the Academic Division Chairman, Deans Committee Chairman, Senate Appeals Committee Chairman, Lectureship Appointments Committee Chairman, Senior Lectureships Appointments Committee Such other duties as may be assigned by the Vice-Chancellor C) MAY 15, 2013 – July 15, 2013: AG. DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR, ACADEMIC AFFAIRS -

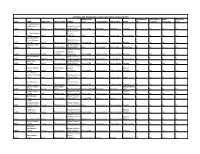

Approved and Operational Health Facilities in Kisumu County

APPROVED AND OPERATIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES IN KISUMU COUNTY REGULATORY OPEN WHOLE OPEN PUBLIC OPEN OPEN LATE CODE NAME KEPH LEVEL FACILITY TYPE OWNER BODY CONSTITUENCY SUB COUNTY WARD DAY HOLIDAYS WEEKENDS NIGHT Tumaini Kopere Health Care Private Practice - 25247 Services Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Muhoroni Muhoroni Chemelil No No No No Private Practice - St. Lucia Medical Nurse / 25071 Centre Level 3 Medical Center Midwifery None Kisumu East Kisumu East Kolwa Central Yes Yes Yes Yes Dalcoo Medical Centre(Kisumu Private Practice - 24971 Central) Level 3 Medical Center Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Kondele Yes Yes Yes Yes Angeline Health Private Practice - 24949 Care Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer None Kisumu East Kisumu East Manyatta B No No Yes No Private Practice - Primary care General 24940 Fairmont Hospital Level 4 hospitals Practitioner Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Railways Yes Yes Yes Yes Good Neighbour Private Practice - 24904 clinic Level 2 Medical Clinic Private Company Pharmacy & PoisonsKisumu Board West Kisumu West West Kisumu No No No Yes Danid Care Private Practice - 24880 Services Level 3 Nursing Homes Clinical Officer Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Kondele Yes Yes Yes Yes Private Practice - Jobefar Medical Basic Health General Market 24824 Centre Level 3 Centre Practitioner Kenya MPDB Kisumu Central Kisumu Central Milimani Yes Yes Yes Yes Peter Plumb Harmony Medical Private Practice - 24817 Clinic Level 2 Medical Clinic Clinical Officer None -

Kisumu County Brochure

U.S. GOVERNMENT INVESTMENTS IN KISUMU COUNTY STRENGTHENING DEMOCRACY AND MUTUAL SECURITY Collaborating with the Government of Kenya and its people to build a peaceful, secure, and democratic society panning more than five decades, The Kenyan Constitution is a remarkable document that is built the U.S.-Kenya partnership is a upon the values of freedom, equality, justice, and human rights – values that are shared by the American people. To achieve tapestry of ties in government, the great promise of Kenya’s Constitution, we will partner with Sbusiness, academia, development, and Kenya to strengthen democratic institutions, address ethnic civil society. Each year, the American divisions, fight corruption, and help ensure freedom of the media and space for civil society. In particular, we are working to people invest close to $1 billion (100 support both the national and county levels of government to billion Kenyan shillings) in Kenya implement devolution. to advance our mutual security, We support Kenyan citizens as they seek to be more actively engaged in their democracy by learning how national and prosperity, and democratic values. county governments work and finding ways for them to have a voice in both. Our investment in Kenya’s future is Human rights and social protections are important to the guided by the great promise of the 2010 security of Kenyans. We collaborate with civil society to ensure Kenya Constitution and Kenya’s own Kenyans can enjoy their human, civil, and labor rights, particularly within marginalized communities. development goals. Through strong Reducing crime and violent extremism ensures greater security partnerships with the national and both at home and around the world.