Zamorins of Calicut from the Earliest Times Down to A.D. 1806

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006-Journal 13Th Issue

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2006 Thirteenth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA September 2006, Thirteenth Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. R.Nagaswami Dr.T.K.Venkatasubramaniam Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. T.K. Venkatasubramaniam Prof. Vijaya Ramaswamy Dr. A. Satyanarayana Published by C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org Subscription Rs.95/- (for 2 issues) Rs.180/-(for 4 issues) 2 September 2006, Thirteenth Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS ANCIENT HISTORY Bhima Deula : The Earliest Structure on the Summit of Mahendragiri - Some Reflections 9 Dr. R.C. Misro & B.Subudhi The Contribution of South India to Sanskrit Studies in Asia - A Case Study of Atula’s Mushikavamsa Mahakavya 16 T.P. Sankaran Kutty Nair The Horse and the Indus Saravati Civilization 33 Michel Danino Gender Aspects in Pallankuli in Tamilnadu 60 Dr. V. Balambal Ancient Indian and Pre-Columbian Native American Peception of the Earth ( Mythology, Iconography and Ritual Aspects) 80 Jayalakshmi Yegnaswamy MEDIEVAL HISTORY Antiquity of Documents in Karnataka and their Preservation Procedures 91 Dr. K.G. Vasantha Madhava Trade and Urbanisation in the Palar Valley during the Chola Period - A.D.900 - 1300 A.D. -

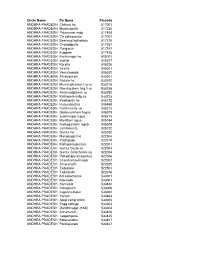

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Details of Crushers in Palakkad District As on Date of Completion of Quarry

Details of crushers in Palakkad District as on date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator Alathur Taluk Aboobacker.V.K, Manager, Aboobacker.V.K, Manager, Malaboor Blue Stone, Malaboor Blue Stone, 523 Kuzhalmannam-II Pullupara Kalapetty. P.O, Kalapetty. P.O, Kuzhalmannam, Palakkad, Kuzhalmannam, Palakkad, Chittur Taluk K.P.Anto, KGP Granites, KGP Granites, K.P.Anto, KGP Granites, 495 Valiyavallampathy Ravanankunnupara Ravanankunnupara, Ravanankunnupara, Ravanankunnupara, P.O.Nattukal P.O.Nattuka P.O.Nattukal Ottapalam Taluk K.abdurahamn, Managing K.abdurahamn, Managing Cresent Stone Creshers, 102 Kulukallur Vandanthara Partner, Crescent Stone Partner, Crescent Stone Mannengod Crusher, Mannengod Crusher, Mannengod New Hajar Indusrties, K.Ummer, Managing 122 Nagalasserry Mooliparambu Partner, Moolipparambu, Kottachira.P.O, Palakkad Antony S. Alukkal, Alukkal Antony S. Alukkal, Alukkal Antony S. Alukkal, Alukkal 125 Thirumittakode II Malayan House, P.O. Kalady, House, P.O. Kalady, House, P.O. Kalady, Ernakulam Ernakulam Ernakulam Abdul Hammed Khan, Jamshid Industries 137 Nagalasserry Kodanad Crusher Unit, Mezhathoor .P.O, Palakkad Abdul Hameed Khan, Abdul Hameed Khan, Abdul Hameed Khan, Jamshid Industries, Crusher Jamshid Industries, Jamshid Industries, 145 Nagalasserry Kodanadu Unit, Mezhathoor.P.O, Crusher Unit, Crusher Unit, Palakkad Mezhathoor.P.O, Palakkad Mezhathoor.P.O, Palakkad Marcose George, Geosons Aggregates, Benny Abraham, 164 Koppam Amayur Cherukunnel, P.O.Amayur, P.O.Amayur Ernakulam Muhammedunni Haji, Muhammedunni Haji, Mabrook Granites, Mabrook Granites,Mabrook Mabrook Granites, 168 Thrithala kottappadom Mabrook Industrial Estate, Industrial Estate, Mabrook Industrial Estate, Kottappadom, Palakkad Kottappadom, Palakkad, Kottappadom, Palakkad, V.V. Divakaran, Sreekrishna V.V. Divakaran, 171 Kappur Kappur Industries, Kalladathoor, Sreekrishna Industries, Palakkad Kalladathoor, Palakkad © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. -

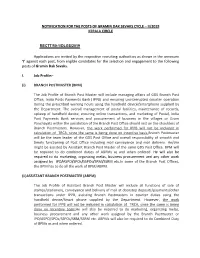

NOTIFICATION for the POSTS of GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE Applications Are Invited by the Respective R

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE RECTT/50-1/DLGS/2019 Applications are invited by the respective recruiting authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’ against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of GDS Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank ( IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device, ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However, the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the GDS Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same GDS Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM etc.In some of the Branch Post Offices, the BPM has to do all the work of BPM/ABPM. -

Assonance a Journal of Russian & Comparative Literary Studies

ISSN 2394-7853 Assonance A Journal of Russian & Comparative Literary Studies No.21 January 2021 Department of Russian & Comparative Literature University of Calicut Kerala – 673635 Assonance: A Journal of Russian & Comparative Literary Studies No.21, January 2021 ISSN 2394-7853 Listed in UGC Care ©2021 Department of Russian & Comparative Literature, University of Calicut Editors: Dr. K.K. Abdul Majeed (Assistant Professor & Head) Dr. Nagendra Shreeniwas (Associate Professor, CRS, SLL&CS, JNU, New Delhi) Sub Editor: Sameer Babu Kavad Board of Referees: 1. Prof. Amar Basu, (Retd.), JNU, New Delhi 2. Prof. Govindan Nair (Retd.), University of Kerala 3. Prof. Ranjana Banerjee, JNU, New Delhi 4. Prof. Kandrapa Das, Guahati University, Assam 5. Prof. Sushant Kumar Mishra, JNU, New Delhi 6. Prof. T.K. Gajanan, University of Mysore 7. Prof. Balakrishnan K, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi 8. Dr. S.S. Rajput, EFLU, Hyderabad 9. Smt. Sreekumari S, (Retd.), University of Calicut, Kerala 10. Dr. V.K. Subramanian, University of Calicut, 11. Dr. Arunim Bandyopadhyay, JNU, New Delhi 12. Dr. K.M. Sherrif, University of Calicut, Kerala 13. Dr. K.M. Anil, Malayalam University, Kerala 14. Dr. Sanjay Kumar, EFLU, Hyderabad 15. Dr. Krishnakumar R.S, University of Kerala Frequency: Annual Published by: Department of Russian & Comparative Literature, University of Calicut, Thenhipalam, Malappuram, Kerala – 673635 Articles in the journal reflect the views of the respective authors only and do not reflect the view of the editors, the journal, the department and/or the university. ii Notes for contributors Assonance is an ISSN, UGC-CARE listed, multilingual, refereed, blind peer reviewed, annual publication of the Department of Russian & Comparative Literature, University of Calicut. -

EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl

LIST OF HIGH SCHOOLS IN MALAPPURAM DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl. Std. Std. HS/HSS/VHSS Boys/G Name of Name of School Address with Pincode Block Taluk No. (Fro (To) /HSS & irls/ Panchayat/Muncip m) VHSS/TTI Mixed ality/Corporation GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS 1 Arimbra GVHSS Arimbra - 673638 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Morayur Malappuram Eranad 2 Edavanna GVHSS Edavanna - 676541 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Edavanna Wandoor Nilambur 3 Irumbuzhi GHSS Irumbuzhi - 676513 VIII XII HSS Mixed Anakkayam Malappuram Eranad 4 Kadungapuram GHSS Kadungapuram - 679321 I XII HSS Mixed Puzhakkattiri Mankada Perinthalmanna 5 Karakunnu GHSS Karakunnu - 676123 VIII XII HSS Mixed Thrikkalangode Wandoor Eranad 6 Kondotty GVHSS Melangadi, Kondotty - 676 338. V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Kondotty Kondotty Eranad 7 Kottakkal GRHSS Kottakkal - 676503 V XII HSS Mixed Kottakkal Malappuram Tirur 8 Kottappuram GHSS Andiyoorkunnu - 673637 V XII HSS Mixed Pulikkal Kondotty Eranad 9 Kuzhimanna GHSS Kuzhimanna - 673641 V XII HSS Mixed Kuzhimanna Areacode Eranad 10 Makkarapparamba GVHSS Makkaraparamba - 676507 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Makkaraparamba Mankada Perinthalmanna 11 Malappuram GBHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Boys Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 12 Malappuram GGHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Girls Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 13 Manjeri GBHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Mixed Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 14 Manjeri GGHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Girls Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 15 Mankada GVHSS Mankada - 679324 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Mankada Mankada -

M. R Ry. K. R. Krishna Menon, Avargal, Retired Sub-Judge, Walluvanad Taluk

MARUMAKKATHAYAM MARRIAGE COMMISSION. ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES BY M. R RY. K. R. KRISHNA MENON, AVARGAL, RETIRED SUB-JUDGE, WALLUVANAD TALUK. 1. Amongst Nayars and other high caste people, a man of the higher divi sion can have Sambandham with a woman of a lower division. 2, 3, 4 and 5. According to the original institutes of Malabar, Nayars are divided into 18 sects, between whom, except in the last 2, intermarriage was per missible ; and this custom is still found to exist, to a certain extent, both in Travan core and Cochin, This rule has however been varied by custom in British Mala bar, in Avhich a woman of a higher sect is not now permitted to form Sambandham with a man of a lower one. This however will not justify her total excommuni cation from her caste in a religious point of view, but will subject her to some social disabilities, which can be removed by her abandoning the sambandham, and paying a certain fine to the Enangans, or caste-people. The disabilities are the non-invitation of her to feasts and other social gatherings. But she cannot be prevented from entering the pagoda, from bathing in the tank, or touch ing the well &c. A Sambandham originally bad, cannot be validated by a Prayaschitham. In fact, Prayaschitham implies the expiation of sin, which can be incurred only by the violation of a religious rule. Here the rule violated is purely a social one, and not a religious one, and consequently Prayaschitham is altogether out of the place. The restriction is purely the creature of class pride, and this has been carried to such an extent as to pre vent the Sambandham of a woman with a man of her own class, among certain aristocratic families. -

District Survey Report of Minor Minerals (Except River Sand)

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF MINOR MINERALS (EXCEPT RIVER SAND) Prepared as per Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 issued under Environment (Protection) Act 1986 by DEPARTMENT OF MINING AND GEOLOGY www.dmg.kerala.gov.in November, 2016 Thiruvananthapuram Table of Contents Page no. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Administration ........................................................................................................................... 3 3 Drainage and Irrigation .............................................................................................................. 3 4 Rainfall and climate.................................................................................................................... 4 5 Other meteorological parameters ............................................................................................. 6 5.1 Temperature .......................................................................................................................... 6 5.2 Relative Humidity ................................................................................................................... 6 5.3 Evaporation ............................................................................................................................ 6 5.4 Sunshine Hours ..................................................................................................................... -

Ss of the Sector Product (S) Enterprise # 1 Haritham Arts&Crafts Traditional Handicraft Thrikaipetta (Po), Nellimalam, Wayanad T-9495240567

NAME & ADDRESS OF THE SECTOR PRODUCT (S) ENTERPRISE # 1 HARITHAM ARTS&CRAFTS TRADITIONAL HANDICRAFT THRIKAIPETTA (PO), NELLIMALAM, WAYANAD T-9495240567 2 ABHIRAMI BAMBOO UNIT TRADITIONAL BAMBOO PAZHUPPATHUR P.O PRODUCTS THEKKINKANDY WAYANAD-673592 T-9539595919 3 AISWARYA NUTIMIX FOOD NUTRIMIX NENMENIKKUNNU P.O PROCESSING SULTHAN BETHERY WAYANAD- 673595 T-9747075572 4 SWATHY CURRY POWDER FOOD CURRY POWDER THAVANI PROCESSING NENMENI P.O KOLIYADI SULTHAN BETHERY WAYANAD MOB: 9605974980 5 VALSALYAM NUTRIMIX FOOD CURRY POWDER/ NENMENI.P.O PROCESSING NUTRIMIX MADAKARA SULTHAN BETHERI WAYANAD MOB: 9656051316 [email protected] OM 6 AISWARYA NUTIMIX FOOD NUTRIMIX NOOLPUZHA PANJAYAT PROCESSING NENMENI KUNNU P.O WAYANAD- 673595 MOB: 9744540040 7 JWALA NUTRIMIX FOOD NUTRIMIX KIDAGANAD P O PROCESSING VADAKKANAD SULTHAN BETHERY WAYANAD MOB: 9961137711 8 JEEVANDHARA NEUTRIMIX FOOD NUTRIMIX KIDAGANAD P.O PROCESSING VADAKKANAD WAYANAD MOB: 9744667166 9 JEEVANDHARA NEUTRIMIX FOOD NUTRIMIX KIDAGANAD P.O PROCESSING VADAKKANAD WAYANAD MOB: 9747574461 10 ATHIRA FOOD PRODUCTS FOOD FOOD PRODUCT K21, USHAS PROCESSING KANIYARAM MANANTHAVADY WAYANAD PH: 04935240185 , 9446648051 11 AYSHA CHEMICALS CHEMICALS DETERGENTS POOTHICAUD POOMALA P O WAYANAD PH: 04936222166 12 KOCHIKUNNEL FOOD FOOD BAKERY PRODUCTS KINFRA PARK PROCESSING PRODUCTS CHUNDEL KALPETTA WAYANAD PH: 04936202707 , 9447042677 KOCHIKUNNELFOODPRODUCTS@G MAIL.COM 13 NAS BAGS OTHERS SHOPPER BAGS PUZHAMUDI P.O KALPETTA WAYANAD T-04936204669 , 9567455570 14 KENZ GARMENTS, GARMENTS READYMADE DWARAKA, -

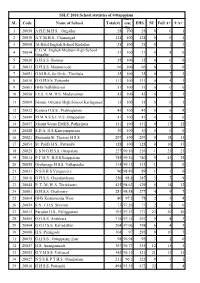

SSLC Result 2016 Result Analysis (PALAKKAD

SSLC 2016:School statistics of Ottappalam Succ SL Code Name of School Total(#) ess( EHS NI Full A+ 9 A+ %) 1 20050 A.H.E.M.H.S. , Ongallur 28 100 28 0 0 1 2 20030 A.V.M.H.S., Chunangad 124 100 124 0 0 1 3 20068 Al-Hilal English School Kudallur 25 100 25 0 1 3 C.G.M. English Medium High School 4 20054 31 100 31 0 8 0 Ongallur 5 20020 G.H.S.S. Shornur 35 100 35 0 0 0 6 20033 G.H.S.S. Munnurcode 66 100 66 0 1 0 7 20051 G.M.R.S. for Girls , Thrithala 35 100 35 0 7 3 8 20010 G.O.H.S.S. Pattambi 111 100 111 0 4 1 9 20061 GHS Nellikkurissi 51 100 51 0 0 0 10 20058 I.E.S. E.M. H.S. Mudavannur 43 100 43 0 3 1 11 20069 Islamic Oriental High School Karinganad 13 100 13 0 0 1 12 20052 Karuna H.S.S., Prabhapuram 43 100 43 0 6 9 13 20049 M.M.N.S.S.E.H.S. Ottappalam 41 100 41 0 0 0 14 20057 Mount Seena EMHS, Pathiripala 151 100 151 0 17 12 15 20028 S.D.A. H S Kaniyampuram 30 100 30 0 0 0 16 20021 Shoranur St. Therese H S S 207 100 207 0 18 11 17 20053 St. Paul's H.S., Pattambi 128 100 128 0 16 15 18 20025 L S N G.H.S.S.