Fairbourne Coastal Risk Management Learning Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dining out in Dolgellau 2014

Dining out in Dolgellau Although a small town, Dolgellau is well served by a variety of great places to eat. Many of these are buildings of interest with a fascinating history so to make sure you are able to enjoy them, please let us know which you would like to visit and we will gladly make a reservation for you. Please note many of these are small, intimate restaurants with a limited number of covers so advance booking is essential. Lemongrass Bangladeshi 01341 421300 0.1 mile Mon ––– SunSunSun Restaurant An excellent friendly, family-run restaurant offering a mouth-watering selection of Indian and Bangladeshi dishes. Y Meirionnydd 01341 44422554 www.themeirionnydd.com 0.2 mile TuTuTu eeesss–––Sat The 'Old County Gaol Restaurant' is situated in the cellar of ‘Y Meirionnydd’ Hotel which was originally the county gaol from 1730 to around 1815. It is well known locally for serving quality local produce at reasonable prices and boasts one of the most comprehensive selections of Welsh wines. Advance booking essential. Y Sospan 01341 423174 www.cottagewww.cottage----inininin----snowdonia.co.uk/sospansnowdonia.co.uk/sospan 0.2 mile Mon ––– SunSunSun Once the town courthouse and jail, Y Sospan is a lovely flagstone floor tearoom and café during the day and a lively bistro at night. Serves a great selection of homemade cakes and local dishes. The Royal Ship 01341 422209 www.royalshiphotel.robinsonsbrewery.com 0.2 mile Mon ––– SatSatSat The Royal Ship is a 19th century coaching inn situated in the heart of the town. Their extensive menu features a great range of traditional favourites along with lighter options and snacks, whilst the daily specials offer a wider choice of finer dining options from around the world. -

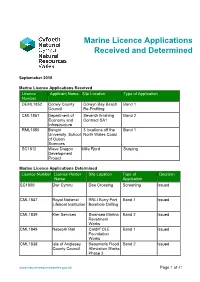

Marine Licence Applications Received and Determined

Marine Licence Applications Received and Determined Septemeber 2018 Marine Licence Applications Received Licence Applicant Name Site Location Type of Application Number DEML1852 Conwy County Colwyn Bay Beach Band 1 Council Re-Profiling CML1851 Department of Seventh finishing Band 2 Economy and Contract SA1 Infrastructure RML1850 Bangor 3 locations off the Band 1 University, School North Wales Coast of Ocean Sciences SC1812 Wave Dragon Milla Fjord Scoping Development Project Marine Licence Applications Determined Licence Number Licence Holder Site Location Type of Decision Name Application SC1809 Dwr Cymru Dee Crossing Screening Issued CML1847 Royal National RNLI Burry Port Band 1 Issued Lifeboat Institution Borehole Drilling CML1839 Kier Services Swansea Marina Band 2 Issued Revetment Works CML1849 Network Rail Cardiff OLE Band 1 Issued Foundation Works CML1838 Isle of Anglesey Beaumaris Flood Band 2 Issued County Council Alleviation Works Phase 2 www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk Page 1 of 41 RML1835 Bridgend County Structural Band 2 Issued Borough Council condition assessment of sea wall, requiring trial pits and horizontal cores August 2018 Marine Licence Applications Received Licence Applicant Name Site Location Type of Application Number CML1849 Network Rail Cardiff OLE Band 1 Foundation Works DML1848 Pembrokeshire Tenby Harbour Band 2 County Council Maintenance Dredging and beach nourish CML1847 Royal National RNLI Burry Port Band 1 Lifeboat Borehole Drilling Institution CML1846 Griffiths DJP1 - Emergency Band 1 Contractors Ltd Repairs -

Planning and Access Committee

R HYBUDD O G YFARFOD / N OTICE OF M EETING Awdurdod Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri Snowdonia National Park Authority Emyr Williams Emyr Williams Prif Weithredwr Chief Executive Awdurdod Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri Snowdonia National Park Authority Penrhyndeudraeth Penrhyndeudraeth Gwynedd LL48 6LF Gwynedd LL48 6LF Ffôn/Phone (01766) 770274 Ffacs/Fax (01766)771211 E.bost/E.mail : [email protected] Gwefan/Website: : www.eryri.llyw.cymru Cyfarfod : Pwyllgor Cynllunio a Mynediad Dyddiad: Dydd Mercher 17 Ionawr 2018 Amser 10.00 y.b. Man Cyfarfod: Plas Tan y Bwlch, Maentwrog. Meeting: Planning and Access Committee Date: Wednesday 17 January 2018 Time: 10.00 a.m. Location: Plas Tan y Bwlch, Maentwrog. Aelodau wedi’u penodi gan Gyngor Gwynedd Members appointed by Gwynedd Council Y Cynghorydd / Councillor : Freya Hannah Bentham, Elwyn Edwards, Alwyn Gruffydd, Annwen Hughes, Edgar Wyn Owen, Elfed Powell Roberts, John Pughe Roberts, Catrin Wager, Gethin Glyn Williams; Aelodau wedi’u penodi gan Gyngor Bwrdeistref Sirol Conwy Members appointed by Conwy County Borough Council Y Cynghorwyr / Councillors : Philip Capper, Chris Hughes, Ifor Glyn Lloyd; Aelodau wedi’u penodi gan Llywodraeth Cymru Members appointed by The Welsh Government Mr. Brian Angell, Ms. Tracey Evans, Mrs. M. June Jones, Mrs. Marian W. Jones, Mr. Ceri Stradling, Mr Owain Wyn. A G E N D A 1. Apologies for absence and Chairman’s Announcements To receive any apologies for absence and Chairman’s announcements. 2. Declaration of Interest To receive any declaration of interest by any members or officers in respect of any item of business. 3. Minutes The Chairman shall propose that the minutes of the meeting of this Committee held on 6th December 2017 be signed as a true record (copy herewith) and to receive matters arising, for information. -

Ras Gyfnewid Bechgyn (4 X 100M) Bl 3 a 4

Athletau Cynradd Cylch Idris Naid Hir Bechgyn Bl 3 a 4 Id Enw Cangen Amser/ Hyd Safle 14225 Iwan Owen Ysgol Gynradd Llanelltyd 2.57 1 14787 Iestyn Edward Jarman Adran Brithdir 2.30 2 14680 Liam Offland Adran Y Friog 2.28 3 14894 Leo Waterhouse Adran Dinas Mawddwy 2.14 4 14679 Jayden Scott Adran Y Friog 2.00 5 14116 C.J Tyrrell Ysgol Gynradd Dolgellau 1.63 6 14115 Joni Edwards Ysgol Gynradd Dolgellau 1.25 7 7 Naid Hir Bechgyn Bl 5 a 6 Id Enw Cangen Amser/ Hyd Safle 14808 Jago Cartwright Adran Brithdir 3.23 1 14908 Gweltaz Llyr Davalan Adran Dinas Mawddwy 2.62 2 14142 Garin Williams Ysgol Gynradd Dolgellau 2.60 3 14143 Jack Roberts Ysgol Gynradd Dolgellau 2.37/2.33 4 14809 Huw Sion Jarman Adran Brithdir 2.37/2.20 5 14235 Gwion Jones Ysgol Gynradd Llanelltyd 2.28 6 12330 Gruffydd Llywelyn Adran Ganllwyd 2.23 7 12329 Morgan Llywelyn Adran Ganllwyd 2.14 8 14692 Brandon Hope Adran Y Friog 1.17 9 9 Naid Hir Merched Bl 3 a 4 Id Enw Cangen Amser/ Hyd Safle 14789 Ffion Mair Adran Brithdir 2.40 1 14895 Glesni Wyn Jones Adran Dinas Mawddwy 2.09 2 14758 Magi Non Jones Adran Rhydymain 1.98 3 14117 Pepper Fothergill Ysgol Gynradd Dolgellau 1.90 4 14226 Tirion Redgrifft Ysgol Gynradd Llanelltyd 1.80 5 14118 Ffion Wynne Jones Ysgol Gynradd Dolgellau 1.70 6 12321 Elen Pike Adran Ganllwyd 1.60 7 14788 Lleucu Hughes Adran Brithdir 1.30 8 14681 Alexis Brittain Adran Y Friog 1.25 9 12320 Martha Florence Gladstone Adran Ganllwyd 1.00 10 10 Naid Hir Merched Bl 5 a 6 Id Enw Cangen Amser/ Hyd Safle 14768 Lowri Cerys Brown Adran Rhydymain 2.54 1 14693 Jaya Baker-Scott -

Pwyllgor Ymgynghorol Harbwr Porthmadog 9/3/16

BARMOUTH HARBOUR CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE 26.03.19 BARMOUTH HARBOUR CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE 26.03.19 PRESENT: Members : Cllr. Gethin Glyn Williams – Chair (Cyngor Gwynedd), Cllr. Eryl Jones-Williams (Gwynedd Council), Cllr. R. Triggs (Barmouth Town Council), Dr John Smith (Barmouth Viaduct Access Group / Three Peaks Race Committee), Cllr. Mark James (RNLI), Mrs Wendy Ponsford (Member of Merioneth Yacht Club), Mr Martin Parouty (Barmouth Harbour Users Group) and Cllr.Brian Woolley (Arthog Community Council) Officers: Llŷr B. Jones (Senior Manager Economy and Community), Barry Davies (Maritime and Country Parks Officer), Glyn Jones (Barmouth Harbour Master), Lowri Haf Evans (Member Support Officer) and Mererid Watt (Translator) Others invited: Sandi Rocca (Barmouth Publicity Society) 1. APOLOGIES: Apologies were received from:- Cllr. Louise Hughes (Gwynedd Council), Councillor Ioan Ceredig Thomas (Cabinet Member - Economy) and Mr Arthur Francis Jones (Senior Harbours Officer). 2. DECLARATION OF PERSONAL INTEREST No declarations of personal interest were received from any members present. 3. MINUTES The Chairman signed the minutes of the previous meeting of this Committee, held on 23 October 2018, subject to amending note (d) sand clearance page 5 from 'moving sand' to 'moving sand dunes' and to also correct note 5 harbour safety page 6 from 'pots and fishing tackle in Aberdyfi' to 'pots and fishing tackle in Barmouth'. It was proposed and seconded that 'matters arising from the minutes' should be a specific item on the agenda. Matters arising from the minutes: (a) Events The Motorcross dates had been confirmed (b) Fairbourne Emergency Telephones Following a review along the coast, it was highlighted that the use of emergency telephones was low. -

Sibrydion (Priceless) Cymunedol Oct–Nov 2019 Issue 66

Local Interest Community News Events Diddordebau Ileol Newyddion Cymunedol Digwyddiadau FREE Sibrydion (Priceless) Cymunedol Oct–Nov 2019 Issue 66 WIN Tickets to Christmas Fair, NEC see p37 Abergwynant Woods, accessed from the Mawddach Trail. Photo by Christine Radford Delivered free to homes in villages: Pick up a copy in: Arthog, Penmaenpool, Fairbourne, Friog, Llwyngwril, Barmouth, Dolgellau, Machynlleth, Rhoslefain, Llanegryn, Llanelltyd, Bontddu, Corris, Tywyn, Pennal, Aberdyfi, Dinas Abergynolwyn, Taicynhaeaf. Mawddwy, Bala, Harlech, Dyffryn (Volunteers also deliver in: Dinas Mawddwy, Tywyn, Ardudwy, Llanbedr Dyffryn Ardudwy, Harlech, Bala, Brithdir, Talybont) Ready to get moving? Ask us for a FREE property valuation Dolgellau – 01341 422 278 Barmouth – 01341 280 527 Professional – 01341 422 278 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] TRUSTED, LOCALLY & ONLINE www.walterlloydjones.co.uk 2 Sibrydion Halloween.pdf 1 13/09/2019 13:03 Christmas Fair 2019.pdf 1 13/09/2019 13:03 C C M M Y Y CM CM MY MY CY CY CMY CMY K K Sibrydion 3 Fireworks Christmas OVER THE LAKE PARTIES 09.11.19 Christmas Book Christmas Day Lunch now Party 6 2 from PLUS Hog Roast, Music, Bar. courses courses Restaurant booking essential. 6.30pm £55.50 £19. 50 FREE ENTRY per person per person It’s party season at NewYearsEve Gala Dinner EAT, DRINK & PLAYING LIVE 5 BE ENTERTAINED courses £49.95 BOOKING per person ESSENTIAL [email protected] Ty’n y Cornel Hotel Bookings: www.tynycornel.co.uk Tal-y-Llyn, Tywyn, 01654 782282 Gwynedd LL36 9AJ 4 Sibrydion Sibrydion 5 Sibrydion After the Summer Cymunedol and Looking Forward Well, I don’t think we have done too badly for weather this summer! Visitors will have had at least some good weather. -

A Differing View from a Former Government Climate Advisor The

A Differing View From A Former Government Climate Advisor Sir John Houghton, an expert in climate change, gave an informative and thought provoking talk about climate change at his visit to Fairbourne Village Hall on Friday 6th June. Sir John explained how we learn about climate change through observations and computer modelling. The main impacts will be more intense heat waves, sea level rise and a more intense hydrological cycle leading to more floods and droughts. However, for FFC members the most startling information given, concerned the way in which the time scales and levels of sea rise were presented. ESTIMATES FROM IPPC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) 2014 – 2050: About 20 cm. Chair 2014 – 2100: Between 40cm and 60 cm. Pete Cole The Infamous 41 Questions…. Vice Chair By now every Fairbourne household should have received a copy of answers to all of Sylvia Stephenson our 41 questions which were put to Gwynedd Council. These answers will soon also Secretary be available on our website (www.fairbournefacingchange.com). Due to the number Angela Ware of acronyms and technical vocabulary used in the answers, the FFC asked for a glossary to be provided to aid understanding. Copies of this are available from the FFC Treasurer Secretary, Angela Ware, and this too will soon be available to view on the FFC website. Beverley Wilkins IMPORTANT NOTICE: FFC PUBLIC MEETINGS – FRIDAY 18TH JULY DONATIONS WELCOME It’s already clear the answers given in the ’41 Questions’ lead to many more questions. Bank Name We need to collate these on your behalf, so please bring them (and any other issues or HSBC views) to the FFC’s forthcoming public meetings which will be held on Friday 18th July. -

Fairbourne Preliminary Coastal Adaptation Masterplan Background Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Glossary Background & History – Why the Need for a Masterplan?

Fairbourne Preliminary Coastal Adaptation Masterplan JULY 2018 Final Issue Cover photo: Inge Phernambucq (29/04/2018) Amendment Record (Amendment ‘0’ being the original) No. Date Amedment Made Made By 0 April 2018 Draft Issue for Internal Review Royal HaskoningDHV 1 July 2018 Updated version after feedback from Gwynedd Council Ymgynghoriaeth Gwynedd Royal HaskoningDHV Consultancy and input from CES Engineering 2 August 2018 Format updates Royal HaskoningDHV Contributors Fairbourne Preliminary 3 Background Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Glossary Coastal Adaptation Masterplan Background & History - Why the need for a Masterplan? The village of Fairbourne is located at the coast within Cardigan Bay, The management and co-ordination approach and the support West of Wales, at the mouth of the Mawddach Estuary (Figure 0-1). groups established by FMF are summarised in Figure 0-2 and Box 1. The village developed over the last 100 years, over the low lying ` coastal plain, extending out from the southern side of the estuary. Social and Economic Group ` Along the open coast, the land is protected by a natural shingle bank, Technical Group ` which has been reinforced with a crest wall to protect the village Education & Engagement Group ` from the sea. The village is protected from flooding from within the Infrastructure Group ` estuary by a tidal embankment that was strengthened in 2013. Multi Agency Major Incidents Response Group Box 1 - Fairbourne Moving Forward Support Groups Bounded by the main West Coast railway line to the south and east, the village comprises some 400 properties, with a community of Moving forward from this, there has been the need for FMF to some 800 residents; a population that can increase to 3000 over the consider how adaptation can happen in practice. -

Bryn Neuadd, School Road Friog, Fairbourne, LL38 2RQ

Chartered Surveyors Auctioneers Estate Agents Established 1862 www.morrismarshall.co.uk Bryn Neuadd, School Road Friog, Fairbourne, LL38 2RQ • Detached 4 bedroom stone built cottage • Garden of approximately 3/4 of an acre • Distant mountain and sea views • Detached outbuilding • In need of modernisation and upgrading • Energy Efficiency Rating = 15 £249,950 TYWYN OFFICE 01654 710 388 [email protected] General remarks A most attractive detached residence traditionally constructed and of considerable character, been originally 2 cottages and part of the rich mining history is the area. The property occupies a quiet elevated position above the village in wooded hillside and has distant sea views. In need of some refurbishment the property offers massive potential and early viewing is strongly recommended Accommodation Entrance Porch 9'5 x 3'6 (2.87m x 1.07m) Wooden entrance door. Wooden windows. Slate Kitchen/Dining Room 17'7 bx 12'10 (5.36m bx flagstone floor. Wooden door to: 3.91m) Two double glazed windows to front with deep Hall 12'0 x 9'12 (3.66m x 3.05m) sills, enjoying open views to front garden and Spacious hall with window to front porch. countyside beyond. Window to Storage/Pantry. Window to lounge. Radiator. Laminate flooring. Range of fitted pine wall and base units. 1½ Beams to ceiling. Stairs to First Floor. Doors to stainless steel sink with drainer, mixer tap and Lounge and rear Sun Room. drinking water tap. Space and point for electric Lounge 15'9 x 13'5 (4.80m x 4.09m) cooker. Space and plumbing for washing Double glazed window to front enjoying open machine. -

Arthog Community Council

ARTHOG COMMUNITY COUNCIL www.cyngorarthogcouncil.cymru MINUTES OF THE COMMUNITY COUNCIL MEETING HELD AT THE ARTHOG VILLAGE HALL HELD WEDNESDAY 5TH JUNE 2019 882: The Chairman Opened the Meeting: The Chairman, Cllr Eves opened the meeting at 7.00 and welcomed all present. 883: Present: Cllr Eves, Cllr Roberts, Cllr Thomas, Cllr Woolley, Cllr (Mrs J Woolley, Cllr (Mrs) R Stott, Cllr (Mrs) H Neville, Cllr (Mrs) L Hughes, and the Clerk Angela Thomas 884: Apologies Received: Cllr Haycock 885: Councillors’ Declaration of Interest: Nil 886: To Receive Any Special Announcements: Nil 887: To Confirm Minutes of the meeting held on 8th May 2019. The Minutes were signed by the Chairman as accurate Approved by Cllr Roberts and Seconded by Cllr (Mrs) Neville 888: Matters Arising from the Minutes of the Meeting held on 8th May 2019 - Nil 889: Clerks Report: The Clerk had requested information from One Voice Wales with reference to the needs of the Website. Guidance had been received and it was felt that the Arthog Community Council Website was up to speed. The Clerk had also reviewed the Risk Assessment for ACC. It is fully up to date therefore the notation from the Internal Auditor is fulfilled. It was shown to the Councillors’, approved by Cllr Thomas and seconded by Cllr Woolley. An email and been sent to all Councillors’ regarding the non-attendance of Lisa Goodier and Emyr Gareth and the explanation as to why they were not attending. All Councillors’ confirmed that they had received the email. The Clerk confirmed that an inspection of the Playpark had been booked for June with ROSPA. -

Sibrydion (Priceless) Cymunedol Feb–Mar 2019 Issue 62

Local Interest Community News Events Diddordebau Ileol Newyddion Cymunedol Digwyddiadau FREE Sibrydion (Priceless) Cymunedol Feb–Mar 2019 Issue 62 Photo: Mark Kendall – photo of Betty Crowther in Ynys Maengwyn Delivered free to homes in villages: Pick up a copy in: Arthog, Penmaenpool, Fairbourne, Friog, Llwyngwril, Barmouth, Dolgellau, Machynlleth, Rhoslefain, Llanegryn, Llanelltyd, Bontddu, Corris, Tywyn, Pennal, Aberdyfi, Dinas Abergynolwyn, Taicynhaeaf. Mawddwy, Bala, Harlech, Dyffryn (Volunteers also deliver in: Dinas Mawddwy, Tywyn, Ardudwy, Llanbedr Dyffryn Ardudwy, Harlech, Bala, Brithdir, Talybont) Ready to get moving? Ask us for a FREE property valuation Dolgellau – 01341 422 278 Barmouth – 01341 280 527 Machynlleth – 01654 702 571 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] TRUSTED, LOCALLY & ONLINE www.walterlloydjones.co.uk When you think about selling your home please contact Welsh Property Services. ‘A big thank you to you both from the bottom of my heart, I so appreciate your care, your professionalism, your support, your kindness, your dogged persistence….I could go on! Amazing’ Ann. Dec 18 ‘Thank you for all the help you have given us at this potentially traumatic time. When people say moving house is stress- ful, I will tell them to go to Welsh property Services. You two ladies have been wonderful, caring thoughtful and helpful’ Val. Dec 18 Please give Jo or Jules a call for a free no obligation valuation. We promise to live up to the testimonials above. 01654 710500 2 Sibrydion Sibrydion A life saver Cymunedol I wish a Happy New Year to all of our readers, advertisers and contributors. I hope that 2019 will bring all you hope for to you and yours. -

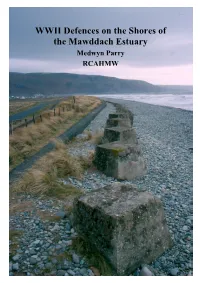

WWII Defences on the Shores of the Mawddach Estuary Medwyn Parry RCAHMW

WWII Defences on the Shores of the Mawddach Estuary Medwyn Parry RCAHMW WWII Defences on the Shores of the Mawddach Estuary Pillbox on the beach at Fairbourne SH 6141 1253 (PR 270356). ‘As England, in spite of the hopelessness of her military position, has so far shown herself unwilling to come to any compromise, I have decided to begin to prepare for, and if necessary to carry out, an invasion of England. This operation is dictated by the necessity of eliminating Great Britain as a base from which the war against Germany can be fought, and if necessary the island will be occupied.’ Directive o. 16, Adolf Hitler, 16 th July 1940 Background When war was declared in September 1939, the notion that Britain would be invaded was almost entirely dismissed. In October, a military exercise ‘The Julius Caesar Plan’ relied in repelling enemy invaders with ‘horsed cavalry’. Military tacticians were complacent in their attitude with home defence, relying on France (with its Maginot Line), Holland & Belgium to provide a considerable invasion ‘buffer zone’. Nothing changed their opinion due to the fact that, with the exception of the invasion of Poland, very little happened in Western Europe for several months – a period known as the “Phoney War”. Events took a dramatic turn after the 9 th of April 1940 - when German forces invaded Denmark and Norway, where the poorly equipped British Expeditionary Force was quickly forced back to Britain. Only a month later, following the stalemate on the borders of the Low Countries, France and Belgium, “Blitzkrieg” burst across the length of the Allied lines.