Penstemon Absarokensis Evert (Absaroka Range Beardtongue): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Thistles of Colorado

Thistles of Colorado About This Guide Identification and Management Guide Many individuals, organizations and agencies from throughout the state (acknowledgements on inside back cover) contributed ideas, content, photos, plant descriptions, management information and printing support toward the completion of this guide. Mountain thistle (Cirsium scopulorum) growing above timberline Casey Cisneros, Tim D’Amato and the Larimer County Department of Natural Resources Weed District collected, compiled and edited information, content and photos for this guide. Produced by the We welcome your comments, corrections, suggestions, and high Larimer County quality photos. If you would like to contribute to future editions, please contact the Larimer County Weed District at 970-498- Weed District 5769 or email [email protected] or [email protected]. Front cover photo of Cirsium eatonii var. hesperium by Janis Huggins Partners in Land Stewardship 2nd Edition 1 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Introduction Native Thistles (Pages 6-20) Barneyby’s Thistle (Cirsium barnebyi) 6 Cainville Thistle (Cirsium clacareum) 6 Native thistles are dispersed broadly Eaton’s Thistle (Cirsium eatonii) 8 across many Colorado ecosystems. Individual species occupy niches from Elk or Meadow Thistle (Cirsium scariosum) 8 3,500 feet to above timberline. These Flodman’s Thistle (Cirsium flodmanii) 10 plants are valuable to pollinators, seed Fringed or Fish Lake Thistle (Cirsium 10 feeders, browsing wildlife and to the centaureae or C. clavatum var. beauty and diversity of our native plant americanum) communities. Some non-native species Mountain Thistle (Cirsium scopulorum) 12 have become an invasive threat to New Mexico Thistle (Cirsium 12 agriculture and natural areas. For this reason, native and non-native thistles neomexicanum) alike are often pulled, mowed, clipped or Ousterhout’s or Aspen Thistle (Cirsium 14 sprayed indiscriminately. -

Plant Species of Special Concern and Vascular Plant Flora of the National

Plant Species of Special Concern and Vascular Plant Flora of the National Elk Refuge Prepared for the US Fish and Wildlife Service National Elk Refuge By Walter Fertig Wyoming Natural Diversity Database The Nature Conservancy 1604 Grand Avenue Laramie, WY 82070 February 28, 1998 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance with this project: Jim Ozenberger, ecologist with the Jackson Ranger District of Bridger-Teton National Forest, for guiding me in his canoe on Flat Creek and for providing aerial photographs and lodging; Jennifer Whipple, Yellowstone National Park botanist, for field assistance and help with field identification of rare Carex species; Dr. David Cooper of Colorado State University, for sharing field information from his 1994 studies; Dr. Ron Hartman and Ernie Nelson of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium, for providing access to unmounted collections by Michele Potkin and others from the National Elk Refuge; Dr. Anton Reznicek of the University of Michigan, for confirming the identification of several problematic Carex specimens; Dr. Robert Dorn for confirming the identification of several vegetative Salix specimens; and lastly Bruce Smith and the staff of the National Elk Refuge for providing funding and logistical support and for allowing me free rein to roam the refuge for plants. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction . 6 Study Area . 6 Methods . 8 Results . 10 Vascular Plant Flora of the National Elk Refuge . 10 Plant Species of Special Concern . 10 Species Summaries . 23 Aster borealis . 24 Astragalus terminalis . 26 Carex buxbaumii . 28 Carex parryana var. parryana . 30 Carex sartwellii . 32 Carex scirpoidea var. scirpiformis . -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

Literature Cited

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volumes 19, 20, and 21, whether as selected references, in text, or in nomenclatural contexts. In citations of articles, both here and in the taxonomic treatments, and also in nomenclatural citations, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991). When those forms are abbre- viated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. In nomenclatural citations (only), book titles are rendered in the abbreviated forms recommended in F. A. Stafleu and R. S. Cowan (1976–1988) and F. A. Stafleu and E. A. Mennega (1992+). Here, those abbreviated forms are indicated parenthetically following the full citations of the corresponding works, and cross references to the full citations are interpolated in the list alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix “a”; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with “b”. Works missing from any suffixed sequence here are ones cited elsewhere in the Flora that are not pertinent in these volumes. -

Floerkea Proserpinacoides Willdenow False Mermaid-Weed

New England Plant Conservation Program Floerkea proserpinacoides Willdenow False Mermaid-weed Conservation and Research Plan for New England Prepared by: William H. Moorhead III Consulting Botanist Litchfield, Connecticut and Elizabeth J. Farnsworth Senior Research Ecologist New England Wild Flower Society Framingham, Massachusetts For: New England Wild Flower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, MA 01701 508/877-7630 e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.newfs.org Approved, Regional Advisory Council, December 2003 1 SUMMARY Floerkea proserpinacoides Willdenow, false mermaid-weed, is an herbaceous annual and the only member of the Limnanthaceae in New England. The species has a disjunct but widespread range throughout North America, with eastern and western segregates separated by the Great Plains. In the east, it ranges from Nova Scotia south to Louisiana and west to Minnesota and Missouri. In the west, it ranges from British Columbia to California, east to Utah and Colorado. Although regarded as Globally Secure (G5), national ranks of N? in Canada and the United States indicate some uncertainly about its true conservation status in North America. It is listed as rare (S1 or S2) in 20% of the states and provinces in which it occurs. Floerkea is known from only 11 sites total in New England: three historic sites in Vermont (where it is ranked SH), one historic population in Massachusetts (where it is ranked SX), and four extant and three historic localities in Connecticut (where it is ranked S1, Endangered). The Flora Conservanda: New England ranks it as a Division 2 (Regionally Rare) taxon. Floerkea inhabits open or forested floodplains, riverside seeps, and limestone cliffs in New England, and more generally moist alluvial soils, mesic forests, springy woods, and streamside meadows throughout its range. -

Sagebrush Identification Guide

Sagebrush Identification Table For Use With Black Light For Use in the Inter-Great Basin Area Fluoresces Under Ultraviolet Branching Mature Plant Plant Nomenclature Light Leaf shape and size Plant Growth Form Environment Comments Pattern Height Water Alcohol Leaves 3/4 ‐1 1/4 in. Uneven topped; Main stem is undivided and trunk‐like at base;. Located long; long narrow; Leaf Uneven normally in drainage bottoms; Small concave areas and valley floors, but will normally be 4 times Colorless to Very topped; always on deep Non‐saline Non‐calcareous soils. Vegetative leader is greater Brownish to longer than it is at its "V"ed Mesic to Frigid 3.5 ft. to Very Pale blue Floral stems than 1/2 the length of the flower stalk from the same single branch. In Basin Basin Big Sagebrush Artemisia Reddish‐Brown widest point; Leaf branching/ Xeric to Ustic greater than 8 tridentata subsp. tridentata (ARTRT) Rarely pale growing there are two growth forms: One the Typical tall form (Diploid); Two a shorter to colorless margins not extending upright 4000 to 8000 ft. ft. Brownish‐red throughout form that looks similar to Wyoming sagebrush if you do not look for the trunk outward; Crushed leaves the crown (around 1 inch or so); the branching pattern; and the seedhead to vegetative have a strong turpentine leader characteristics (Tetraploid). smell Uneven Leaves 1/2 ‐ 3/4 inches topped; Uneven topped; Main stem is usually divided at ground level. Plants will often Mesic to Frigid Wyoming Big Sagebrush Colorless to Very Colorless to pale long; Leaf margins curved Floral stems Spreading/ keep the last years seed stalks into the following fall. -

Riverside State Park

Provisonal Report Rare Plant and Vegetation Survey of Riverside State Park Pacific Biodiversity Institute 2 Provisonal Report Rare Plant and Vegetation Survey of Riverside State Park Peter H. Morrison [email protected] George Wooten [email protected] Juliet Rhodes [email protected] Robin O’Quinn, Ph.D. [email protected] Hans M. Smith IV [email protected] January 2009 Pacific Biodiversity Institute P.O. Box 298 Winthrop, Washington 98862 509-996-2490 Recommended Citation Morrison, P.H., G. Wooten, J. Rhodes, R. O’Quinn and H.M. Smith IV, 2008. Provisional Report: Rare Plant and Vegetation Survey of Riverside State Park. Pacific Biodiversity Institute, Winthrop, Washington. 433 p. Acknowledgements Diana Hackenburg and Alexis Monetta assisted with entering and checking the data we collected into databases. The photographs in this report were taken by Peter Morrison, Robin O’Quinn, Geroge Wooten, and Diana Hackenburg. Project Funding This project was funded by the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission. 3 Executive Summary Pacific Biodiversity Institute (PBI) conducted a rare plant and vegetation survey of Riverside State Park (RSP) for the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (WSPRC). RSP is located in Spokane County, Washington. A large portion of the park is located within the City of Spokane. RSP extends along both sides of the Spokane River and includes upland areas on the basalt plateau above the river terraces. The park also includes the lower portion of the Little Spokane River and adjacent uplands. The park contains numerous trails, campgrounds and other recreational facilities. The park receives a tremendous amount of recreational use from the nearby population. -

PLANT LIST for POLLINATORS Part 1 – a Concise List of Suggested Garden Plants That Are Attractive to Pollinating Insects

THE ACTION PLAN FOR POLLINATORS SUGGESTED PLANT LIST FOR POLLINATORS Part 1 – A concise list of suggested garden plants that are attractive to pollinating insects This is a list of suggested garden plants. We have only selected flowers which are garden- worthy, easily obtainable, well-known, and widely acknowledged as being attractive to pollinating insects. In some case we have given extra comments about garden- worthiness. This is intended as a clear and concise short list to help gardeners; it is not intended to be comprehensive and we have avoided suggesting plants which are difficult to grow or obtain, or whose benefit to pollinators is still a matter for debate. We have omitted several plants that are considered to have invasive potential, and have qualified some others on the list with comments advising readers how to avoid invasive forms. PLANT ANGELICA (Angelica species). Attractive to a range of insects, especially hoverflies and solitary bees. AUBRETIA (Aubrieta deltoides hybrids). An important early nectar for insects coming out of hibernation. BELLFLOWER (Campanula species and cultivars). Forage for bumblebees and some solitary bees. BETONY (Stachys officinalis). Attractive to bumblebees. Butterfly Conversation’s Awarded the Royal Horticultural Top Butterflys Society’s ‘Award of Garden Nectar Plants. Merit’. PLANT BIRD’S FOOT TREFOIL (Lotus corniculatus). Larval food plant for Common Blue, Dingy Skipper and several moths. Also an important pollen source for bumblebees. Can be grown in gravel or planted in a lawn that is mowed with blades set high during the flowering period. BOWLES’ WALLFLOWER (Erysimum Bowles Mauve). Mauve perennial wallflower, long season nectar for butterflies, moths and many bee species. -

Sagebrush Ecology of Parker Mountain, Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2016 Sagebrush Ecology of Parker Mountain, Utah Nathan E. Dulfon Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dulfon, Nathan E., "Sagebrush Ecology of Parker Mountain, Utah" (2016). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 5056. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/5056 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SAGEBRUSH ECOLOGY OF PARKER MOUNTAIN, UTAH by Nathan E. Dulfon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Range Science Approved: _________________ _________________ Eric T. Thacker Terry A. Messmer Major Professor Committee Member __________________ ___________________ Thomas A. Monaco Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2016 ii Copyright © Nathan E. Dulfon 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Sagebrush Ecology of Parker Mountain, Utah by Nathan E. Dulfon, Master of Science Utah State University, 2016 Major Professor: Dr. Eric T. Thacker Department: Wildland Resources Parker Mountain, is located in south central Utah, it consists of 153 780 ha of high elevation rangelands dominated by black sagebrush (Artemisia nova A. Nelson), and mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata Nutt. subsp. vaseyana [Rybd.] Beetle) communities. Sagebrush obligate species including greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) depend on these vegetation communities throughout the year. -

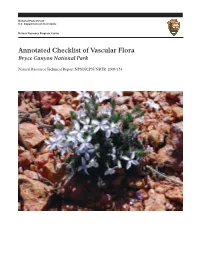

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Bryce

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Bryce Canyon National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR–2009/153 ON THE COVER Matted prickly-phlox (Leptodactylon caespitosum), Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah. Photograph by Walter Fertig. Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Bryce Canyon National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR–2009/153 Author Walter Fertig Moenave Botanical Consulting 1117 W. Grand Canyon Dr. Kanab, UT 84741 Sarah Topp Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 January 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientifi c community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifi cally credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. The Natural Resource Technical Report series is used to disseminate the peer-reviewed results of scientifi c studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service’s mission. The reports provide contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations.