A Review of Taiwanese Trust in the Police with Alternative Interpretations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Science & Information Technology (CS &

Computer Science & Information Technology 143 David C. Wyld, Dhinaharan Nagamalai (Eds) Computer Science & Information Technology 11th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology (CCSIT 2021), May 29~30, 2021, Vancouver, Canada. AIRCC Publishing Corporation Volume Editors David C. Wyld, Southeastern Louisiana University, USA E-mail: [email protected] Dhinaharan Nagamalai (Eds), Wireilla Net Solutions, Australia E-mail: [email protected] ISSN: 2231 - 5403 ISBN: 978-1-925953-41-1 DOI: 10.5121/csit.2021.110701 - 10.5121/csit.2021.110718 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the International Copyright Law and permission for use must always be obtained from Academy & Industry Research Collaboration Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the International Copyright Law. Typesetting: Camera-ready by author, data conversion by NnN Net Solutions Private Ltd., Chennai, India Preface The 11th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology (CCSIT 2021), May 29~30, 2021, Vancouver, Canada, 9th International Conference on Signal, Image Processing and Pattern Recognition (SIPP 2021), 10th International Conference on Parallel, Distributed Computing Technologies and Applications (PDCTA 2021), 9th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Soft Computing (AISC 2021), 2nd International Conference on Natural Language Processing & Computational Linguistics (NLPCL 2021), 2nd International conference on Big Data, Machine learning and Applications (BIGML 2021) and 6th International Conference on Networks, Communications, Wireless and Mobile Computing (NCWMC 2021) was collocated with 11th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology (CCSIT 2021). -

How Taiwan's Constitutional Court Reined in Police Power

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham International Law Journal Volume 37, Issue 4 2014 Article 10 How Taiwan’s Constitutional Court Reined in Police Power: Lessons for the People’s Republic of China Margaret K. Lewis∗ Jerome A. Coheny ∗Seton Hall University School of Law yNew York University School of Law Copyright c 2014 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj ARTICLE HOW TAIWAN’S CONSTITUTIONAL COURT REINED IN POLICE POWER: LESSONS FOR THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA* Margaret K. Lewis & Jerome A. Cohen INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 864 I. THE LEGAL REGIME FOR PUNISHING LIUMANG ........... 866 II. STRUCTURE OF CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW ................. 871 III. INITIAL JUDICIAL INVOLVEMENT IN CURBING POLICE POWER ................................................................ 878 IV. INTERPRETATION NO. 636 ................................................ 882 A. Definition of Liumang and the Principle of Legal Clarity ........................................................................... 883 B. Power of the Police to Force Suspected Liumang to Appear .......................................................................... 891 C. Right to Be Heard by the Review Committee .............. 894 D. Serious Liumang: Procedures at the District Court Level ............................................................................. -

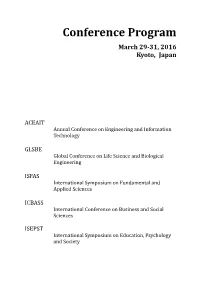

Conference Program

Conference Program March 29-31, 2016 Kyoto, Japan ACEAIT Annual Conference on Engineering and Information Technology GLSBE Global Conference on Life Science and Biological Engineering ISFAS International Symposium on Fundamental and Applied Sciences ICBASS International Conference on Business and Social Sciences ISEPST International Symposium on Education, Psychology and Society ACEAIT Annual Conference on Engineering and Information Technology ISBN 978-986-89298-6-9 GLSBE Global Conference on Life Science and Biological Engineering ISBN 978-986-5654-38-2 ISFAS International Symposium on Fundamental and Applied Sciences ISBN 978-986-89298-5-2 ICBASS International Conference on Business and Social Sciences ISBN 978-986-89298-7-6 ISEPST International Symposium on Education, Psychology and Society ISBN 978-986-89298-8-3 Content General Information for Participants ...................................................................................... 6 International Committees ............................................................................................................ 8 International Committee of ACEAIT ...................................................................................... 8 International Committee of GLSBE ........................................................................................ 9 International Committee of ISFAS ........................................................................................ 10 International Committee of ICBASS .................................................................................... -

Environmental Sciences/ Fundamental & Applied Sciences18 Social Studies / Psychology/ Business Management

Conference Program July 24-26, 2019 Bali, Indonesia ISEAS International Symposium on Engineering and Applied Science ICSSB International Conference on Social Science and Business ISEAS International Symposium on Engineering and Applied Science ISBN 978-986-5654-28-3 ICSSB International Conference on Social Science and Business ISBN 978-986-87417-7-5 Content Welcome Message ............................................................................................................................ 2 General Information for Participants ....................................................................................... 3 International Committees of Natural Sciences ...................................................................... 5 International Committees of Social Sciences.......................................................................... 8 Special Thanks to Session Chairs .............................................................................................. 11 Conference Venue Information ................................................................................................. 12 Conference Schedule ..................................................................................................................... 14 Natural Sciences Keynote Address ........................................................................................... 16 Social Sciences Keynote Address .............................................................................................. 17 Oral Sessions ................................................................................................................................... -

Musical Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule: a Historical and Ethnomusicological Interpretation

MUSICAL TAIWAN UNDER JAPANESE COLONIAL RULE: A HISTORICAL AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION by Hui‐Hsuan Chao A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, Chair Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Jennifer E. Robertson Associate Professor Amy K. Stillman © Hui‐Hsuan Chao 2009 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout my years as a graduate student at the University of Michigan, I have been grateful to have the support of professors, colleagues, friends, and family. My committee chair and mentor, Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, generously offered his time, advice, encouragement, insightful comments and constructive criticism to shepherd me through each phase of this project. I am indebted to my dissertation committee, Professors Judith Becker, Jennifer Robertson, and Amy Ku’uleialoha Stillman, who have provided me invaluable encouragement and continual inspiration through their scholarly integrity and intellectual curiosity. I must acknowledge special gratitude to Professor Emeritus Richard Crawford, whose vast knowledge in American music and unparallel scholarship in American music historiography opened my ears and inspired me to explore similar issues in my area of interest. The inquiry led to the beginning of this dissertation project. Special thanks go to friends at AABS and LBA, who have tirelessly provided precious opportunities that helped me to learn how to maintain balance and wellness in life. ii Many individuals and institutions came to my aid during the years of this project. I am fortunate to have the friendship and mentorship from Professor Nancy Guy of University of California, San Diego. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE IVAN Y. SUN Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice University of Delaware Newark, DE 19716 [email protected] (302) 831-8727 EDUCATION 2000 Ph.D. in Criminal Justice University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York. 1997 M.A. in Criminal Justice University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York. 1992 M.B.A. in Logistics, Operation, and Materials Management George Washington University, Washington D.C. 1982 B.A. in Economics Fu-Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, Taiwan. EMPLOYMENT Teaching 09/12 – Present Professor, Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. 09/05 – Present Faculty, Asian Studies, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. 09/06 – 08/12 Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. 09/04 – 08/06 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. 07/00 – 08/04 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA. 01/98 – 05/99 Graduate Teaching Instructor, School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, NY. Research 05/96 – 08/96 Field Observer, Project on Policing Neighborhoods (POPN), School of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. Visiting Teaching/Research Professor 10/17 School of Law, Institute of Criminology, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium 09/17 School of Sociology, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China 03/11 Department of Applied Social Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. 09/10 – 01/11 Graduate Institute of Criminology, National Taipei University, New Taipei City, Taiwan. -

NIELSON-THESIS-2020.Pdf (850.0Kb)

ATTITUDINAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FEMALE AND MALE POLICE CADETS/OFFICERS IN TAIWAN: THE NEXUS BETWEEN GENDER, IMMIGRATION, AND CRIME ___________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology Sam Houston State University ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ___________ by Kyler R. Nielson August, 2020 ATTITUDINAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FEMALE AND MALE POLICE CADETS/OFFICERS IN TAIWAN: THE NEXUS BETWEEN GENDER, IMMIGRATION, AND CRIME by Kyler R. Nielson ___________ APPROVED: Jurg Gerber, PhD Thesis Director Yan Zhang, PhD Committee Member Furjen Deng, PhD Committee Member Phillip Lyons, PhD Dean, College of Criminal Justice DEDICATION This is dedicated to Amanda, Kenna, and Emmie for their constant love and support through it all. iii ABSTRACT Nielson, Kyler R., Attitudinal differences between female and male police cadets/officers in Taiwan: the nexus between gender, immigration, and crime. Master of Arts (Criminal Justice and Criminology), August, 2020, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. Immigration is an increasingly salient issue throughout the world as the number of foreign residents continues to rise in many countries. In Taiwan, the foreign population has consistently increased in recent years. Immigrants in Taiwan are marginalized and are often subject to negative stereotypes from the media and public. As members of the public, police cadets/officers may be affected by such sentiments, but they should also maintain a neutral perspective and ensure equal treatment in various criminal justice processes. In particular, attitudes may differ based on cadet/officer gender. Males and females may have unique experiences in policing and inherent attitudinal differences. -

Wayfinding of Firefighters in Dark and Complex Environments

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Wayfinding of Firefighters in Dark and Complex Environments Beckham Shih-Ming Lin 1 , Ching-Yuan Lin 1, Chun-Wei Kung 2, Yong-Jun Lin 3, Chung-Chyi Chou 4, Ying-Ji Chuang 1 and Gary Li-Kai Hsiao 5,* 1 Department of Architecture, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei City 106335, Taiwan; [email protected] (B.S.-M.L.); [email protected] (C.-Y.L.); [email protected] (Y.-J.C.) 2 Department of Environmental Engineering, Da-Yeh University, Changhua 515006, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Center for Weather Climate and Disaster Research, National Taiwan University, Taipei City 10617, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 Department of Fire and Safety, Da-Yeh University, Changhua 515006, Taiwan; [email protected] 5 Department of Disaster Management, Taiwan Police College, Taipei City 11696, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Firefighters searching in dark and complex environments might lose their orientation and endanger themselves at the fireground. This study conducted experiments in the Training Facility of the New Taipei City Fire Department (NTFD), Taiwan. The objective of the experiments was to analyze the profile of each firefighter by a 13-factor self-report survey and their wayfinding time in dark and complex environments (DCEs). The results showed that age might be a marginally significant factor, and fear of confinement might be a significant factor that could affect firefighters’ wayfinding time in the DCEs. The findings could provide strategies for improving the safety of Citation: Lin, B.S.-M.; Lin, C.-Y.; firefighters working in such environments. -

A Community Policing Project in Taiwan

Chinese Public Administration CPAR Review Volume xx Issue x, Online First A Community Policing Project in Taiwan: The Developments, Challenges, and Prospects of Neighborhood Watch Fei-Lin Chen Taiwan Police College, Taiwan Neighborhood Watch is a community crime prevention program organized mainly by local residents to maintain order and deter crime. Neighborhood Watch is an important element of community policing in Taiwan. Relying on previous research, this study illustrates the implementation process of Neighborhood Watch in Taiwan. Starting in the 1970s, Neighborhood Watch in Taiwan evolved through several stages, shifting from a focus on moral alignment to community building and crime prevention. The central pillar of Neighborhood Watch is civilian patrol groups commonly organized by either the government at all levels as part of their civilian defense scheme or neighborhood patrol squads staffed by local volunteers. The organization and resources associated with Neighborhood Watch elucidate the government’s intention to integrate the program into community policing as an effective tool for building community safety and strengthening crime prevention. It is reasonable to predict that the Taiwanese government and police are likely to continue their support for the operation of Neighborhood Watch as part of collective efforts to build healthy and safe communities. Keywords: Neighborhood Watch; Taiwan police; civilian patrol squads; community policing; Taiwan INTRODUCTION policing in general (Kuo, & Shih, 2018; Wang, 2007) and Neighborhood Watch programs in Taiwan eighborhood Watch has received much in particular (Lee et al., 2000), none of them have attention in recent years due to its crime analyzed the implementation of Neighborhood Watch Nprevention value, which strengthens informal with a focus on policy analysis. -

TAIWAN's RECENT ELECTIONS: FULFILLING the DEMOCRATIC PROMISE John F

TAIWAN'S RECENT ELECTIONS: FULFILLING THE DEMOCRATIC PROMISE John F. Copper TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface . 1 Chapter 1 Political Change and Elections: 1985-89 . 3 Chapter 2 The 1985 Nationwide Local Elections......... 27 Chapter 3 The 1986 National Election. 45 Chapter 4 The 1989 National and Local Elections . 65 Chapter 5 Summary and Conclusions. 87 Appendix I Public Officials Election and Recall Law . 103 Appendix II Civic Organization Law (excerpts) . 145 Appendix III Statute on the Voluntary Retirement of Senior Parliamentarians . 151 Appendix IV Election Statistics . 157 Selected Bibliography . 159 Index....................................................... 165 About the Author . 175 PUBLISHER'S NOTE Chapters 2, 3 and 4 of this work were taken from articles written by the author and previously published in the following journals: Chapter 2, Asian Affairs, Spring 1986, pp. 27-45 Chapter 3, Asian Thought and Society, July 1987, pp. 115-136 Chapter 4, Journal of Northeast Asian Studies, Spring 1990, pp. 22-40 The publisher wishes to thank these journals for permissions granted. The articles were edited or shortened for use here. PREFACE In 1984, the author, with Professor George P. Chen, published the book Taiwan's Elections: Political Development and Democratiza tion in the Republic of China. We assessed Taiwan's political system as it related to election politics, early local elections, national supple mentary elections beginning in 1969, and the watershed competitive national election in 1980--which inaugurated democratic politics in Taiwan at the national level. That work also included a chapter on the 1983 national election, which proved to many observers that the 1980 election had not been just a show offered during an "election holiday" or a temporary democratic event. -

Open Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE AGE-CRIME RELATIONSHIP ACROSS TIME AND OFFENSE TYPES: A COMPARISON OF THE UNITED STATES AND TAIWAN A Thesis in Sociology by Hua Zhong © 2005 Hua Zhong Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2005 The thesis of Hua Zhong was reviewed and approved* by the following: Darrell Steffensmeier Professor of Sociology and Crime, Law and Justice Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee Eric Silver Associate Professor of Sociology and Crime, Law and Justice Jeffery Ulmer Associate Professor of Sociology and Crime, Law and Justice Rukmalie Jayakody Associate Professor of Human Development and Family Studies and Demography Paul Amato Professor of Sociology and Demography Head of the Department of Department of Sociology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Although scholars agree that crime tends to rise and peak in adolescence or early adulthood and decline afterwards, there is a contentious debate in the criminological literature about whether and to what extent the shape or form of the age-crime curve varies across historical periods, geographic locations, and crime types. The invariancy view, most strongly articulated by Hirschi and Gottfredson (1983), is that the age-crime relationship is universal and invariant across all social and cultural conditions and all social groups at all times. Writers holding the variancy position contend (e.g., Greenberg 1985; Steffensmeier, Allan, Harer and Streifel 1989; Tittle and Grasmick 1998) that there is fact considerable variation across crime types and across countries or historical periods. -

Taiwan, March 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Taiwan, March 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAIWAN March 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Taiwan (台灣); formally, Republic of China (Chung-hua Min-kuo—中華民國). Short Form: Taiwan (台灣). Term for Citizen(s): Chinese (Hua-jen—華人); Taiwanese (T’ai-wan-jen—台灣 人). Capital: The capital of central administration of Taiwan is Click to Enlarge Image Taipei (T’ai-pei—台北—literally, Taiwan North), located in T’ai-pei County in the north. Since 1967, Taipei has been administratively separate from Taiwan Province. Major Cities: The largest city is Taipei, with 2.6 million inhabitants in 2004. Other large cities are Kao-hsiung, with 1.5 million, and T’ai-chung, with 1 million. Fifteen other cities have populations ranging from 216,000 to 749,000 inhabitants. National Public Holidays: Founding Day (January 1, marking the founding of the Republic of China in 1912); Lunar New Year (also called Spring Festival, based on the lunar calendar, occurs between January 21 and February 19 and is preceded by eight days of preparatory festivities); Peace Memorial Day (February 28, commemorating the February 28, 1947, incident); Tomb Sweeping Day (Ching Ming, April 4); Dragon Boat Festival (fifth day of the fifth lunar month, movable date in June); Mid-Autumn Festival (15th day of the eighth lunar month, movable date in September); and Double Tenth National Day (October 10, also called Republic Day, commemorates the anniversary of the Chinese revolution in 1911 and the date from which years are sometimes counted). Also