Deniz Kandiyoti POST-COLONIALISM COMPARED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Myths and Feminist Fables: Repositioning Gender in Development Policy and Practice Workshop

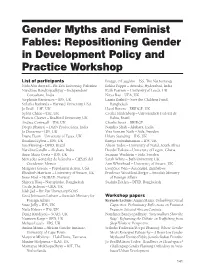

Gender Myths and Feminist Fables: Repositioning Gender in Development Policy and Practice Workshop List of participants Bridget O’Laughlin – ISS, The Netherlands Nida Abu Awwad – Bir Zeit University, Palestine Rekha Pappu – Anveshi, Hyderabad, India Nandinee Bandyopadhyay – Independent Ruth Pearson – University of Leeds, UK Consultant, India Nitya Rao – UEA, UK Stephanie Barrientos – IDS, UK Lamia Rashid – Save the Children Fund, Srilatha Batliwala – Harvard University, USA Bangladesh Jo Beall – LSE, UK Hazel Reeves – BRIDGE, UK Sylvia Chant – LSE, UK Cecilia Sardenberg – Universidade Federal de Francis Cleaver – Bradford University, UK Bahia, Brazil Andrea Cornwall – IDS, UK Charlie Sever – BRIDGE Deepa Dhanraj – D&N Productions, India Nandita Shah – Akshara, India Jo Doezema – IDS, UK Ylva Sornam Nath – Sida, Sweden Diane Elson – University of Essex, UK Hilary Standing – IDS, UK Rosalind Eyben – IDS, UK Ramya Subrahmanian – IDS, UK Sue Fleming – DFID, Brazil Alison Todes – University of Natal, South Africa Nandita Gandhi – Akshara, India Dzodzi Tsikata – University of Legon, Ghana Anne Marie Goetz – IDS, UK Susanne Wadstein – Sida, Sweden Mercedes Gonzalez de la Rocha – CIESAS del Sarah White – Bath University, UK Occidente, Mexico Ann Whitehead – University of Sussex, UK Margaret Greene – Population Action, USA Everjoice Win – ActionAid, Zimbabwe Elizabeth Harrison – University of Sussex, UK Prudence Woodford-Berger – Swedish Ministry Irene Hoel – NORAD, Norway of Foreign Affairs Shireen Huq – Narriphoko, Bangladesh Sushila Zeitlyn -

Repositioning Feminisms in Gender and Development

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs Introduction: Repositioning Feminisms in Gender and Development Andrea Cornwall, Elizabeth Harrison and Ann Whitehead* 1 Introduction convictions (cf. Sorel 1941).2 Women appear in This IDS Bulletin reflects on the contested relationship these representations as abject3 victims, the passive between feminism and development, and the subject of development’s rescue, and splendid challenges for reasserting feminist engagement with heroines, whose unsung virtues and whose development as a political project. It arises from a contributions to development need to be heeded. workshop held at the Institute of Development In many ways, the generalisations that are now Studies and the University of Sussex in July 2003.1 part of the currency of gender and development Centred on how to “reposition” gender and represent a success story. Originating in the development, the workshop debates pointed to the discourses of a minority of politically motivated politics of discourse as a key element in social advocates for gender change, they are now taken transformation. Participants explored how, after for granted and espoused by people occupying initial struggles to develop new concepts and many different spaces in a multitude of development languages for understanding women’s position in institutions. But the extent of change in women’s developing societies, feminist phrases came to be lives does not match this discursive landslide. For filled with new meanings as they were taken up many gender and development advocates, it appears into development policy and practice. Discussions that the more women and poverty are equated in turned on the ambiguous fruits of these struggles development discourse, the more many women and their implications for feminist engagement with experience entrenched poverty; the more gender development. -

Gender and Globalization WSTD 335/ Soc 335 Winter 2012

Gender and Globalization WSTD 335/ Soc 335 Winter 2012 Class Hours: Tues / Thurs Professor: Rachel Rinaldo 4:00 – 5:30 p.m. 2162 Lane Hall 3254 LSA [email protected] Professor’s Office Hours: Wednesday 9:30 – 11:30 Email for appointments at other times Overview: Our world is becoming increasingly interconnected, through technology, economics, politics, migration, and cultural imaginations. This class will explore how global processes are affecting gender in different parts of the world, how gender itself shapes aspects of globalization, and the potential for feminist transformations. We will begin by considering what it means to think about gender from a global perspective, including post-colonial critiques of feminism. We will continue on to examine themes such as the impact of economic globalization on gender relations, gendered work in the global economy, sex work, how global processes are re-shaping love and family, gender and religion in global context (especially debates over women and Islam), changing masculinities, as well as women’s movements and the impact of transnational feminisms. Students will be encouraged to apply the course material to real world examples of global gender issues. TEXTS FOR PURCHASE The following books have been ordered for purchase. Most journal articles and chapters out of other books will be posted on Ctools (subject to copyright restrictions. You may need to use the library to find some readings. All of the reading on the syllabus is required unless it is specifically listed as “recommended.” I will expect you to bring your copies of the readings to each class. Most of these books can be easily bought secondhand for low prices. -

Symposium: Populisms in the World-System 294

JOURNAL OF WORLD-SYSTEMS RESEARCH ISSN: 1076-156X | Vol. 24 Issue 2 | DOI 10.5195/JWSR.2018.853 | jwsr.pitt.edu SYMPOSIUM: POPULISMS IN THE W ORLD-SYSTEM Gendering the New Right-Wing Populisms: A Research Note Valentine M. Moghadam Northeastern University [email protected] Abstract Populism has become the subject of a large and growing literature but little is written about non-Western movements, and feminist scholars have yet to grapple with its gender dynamics, including its appeal to many women voters, and its gendered social consequences. In this research note, I briefly survey the literature and show how right-wing populist nationalism – a reaction to the ills of neoliberal capitalist globalization – is also found in Islamist movements. I call for an inclusive, progressive agenda that can appeal to and mobilize those who have been left behind. Keywords: Islamist movements, gender Articles in vol. 21(2) and later of this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System, University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Journal of World-System Research | Vol. 24 Issue 2 | Symposium: Populisms in the World-System 294 Is the specter of populism haunting the contemporary world? The sheer number of publications on the subject since at least 2016 suggests its topicality and urgency.1 Most studies focus on the rise of right-wing radical populist parties and movements, although left-wing populist movements and parties also have erupted. -

Spellman CV 2006

25 Florence Street London N1 2DX Fax: +44 (0) 870 130 8069 Tel: +44 (0) 7949 486 831 [email protected] Dr. Kathryn Spellman Personal National Insurance Number: PC557120A/A Information Work permit not required. Employment/Posts 2001-Present Huron International University London Full-time Associate Professor Researched, designed and taught the following courses: Religion, Identity and Power Migration and Diasporas Gender, Nation and Development Modern Social Theory January 2003 - Present Syracuse University London Adjunct Professor Researched, designed and taught the following courses: Religion, Identity and Power Migration and Diasporas Multicultural London January 2005 - Present London Middle East Institute, SOAS London Research Associate and Editorial Board Member – Middle East in London Magazine September 2005 – Present Al-Fatah University Tripoli, Libya Research Fellow April 2004 University of Sussex Falmer Tutor • Theories and Contexts of Sociological Inquiry June 2002 – Present Visiting Research Fellow Sussex Centre For Migration Research and Centre For Culture, Development and Environment Education 1995-2000 Birkbeck College, University of London London Ph.D. Sociology Successfully defended viva voce examination 2 June 2000. Title of thesis: ‘Religion, Nation and Identity: Iranians in London’. Supervisor: Sami Zubaida Examiners: Joanna de Groot and Deniz Kandiyoti 1994-95 Birkbeck College, University of London London Master of Science (MSc.) in Politics and Sociology Religion, Culture and Politics Race, Ethnicity and Law Social Theory Political Sociology 1991-94 Richmond International University London Bachelor of Art (BA) with Honours in Combined Social Sciences 1989-91 Marquette University Milwaukee / USA Major area of study Sociology Publications Publications Books Religion and Nation: Iranian Local and Transnational Networks in London , Berghahn Books, Oxford and New York, 2005. -

AKU-ISMC Book Launch: Gender, Governance and Islam (17 Oct 2019, London)

H-Levant ANNC: AKU-ISMC Book Launch: Gender, Governance and Islam (17 Oct 2019, London) Discussion published by Layal Mohammad on Friday, August 23, 2019 Join us for a panel discussion by the editors followed by a reception to celebrate the launch of AKU-ISMC’s new book: “Gender, Governance and Islam” edited by Deniz Kandiyoti, Nadje Al-Ali and Kathryn Spellman Poots. Abstracts Deniz Kandiyoti - Gender, Governance and Islam Introducing the key themes of the book which was compiled against a global backdrop of mounting culture wars in the realms of gender, family and sexuality, Deniz Kandiyoti will discuss its aims to unsettle and interrogate the key conceptual categories through which the politics of gender in Muslim-majority countries and Muslim diasporas have been commonly apprehended. It does so through finely-grained analyses of a continuum of cases: fragmented societies that are in the grip of ongoing conflict such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Palestine (that are characterised by more direct interventions by global governance institutions), Pakistan that has been directly affected by conflict, Turkey and Egypt that have undergone popular unrest and regime change and the “Islamic” regimes in Saudi Arabia and Iran that have undergone major transformations. The particular alignments of changing geo-politics, the inroads made by international gender platforms, their instrumental use (and misuse) by power holders, the stakes of diverse Islamic actors in the politics of gender and patterns of grass-roots mobilisation and resistance are illustrated with reference to selected cases. Efforts to enforce gender hierarchies and uphold male entitlement on the one hand, and diverse patterns of grassroots resistance and (periodic accommodation by power holders), on the other, cut across all cases. -

Nadje Sadig Al-Ali Address: Watson Institute for Public and International

CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Data: Name: Nadje Sadig Al-Ali Address: Watson Institute for Public and International Affairs 111 Thayer Street Providence, RI 02912 +1 (401) 863-5129 [email protected] 2. Education: September 1998 PhD The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London - U.K. Department of Social Anthropology February 1993 Masters of Arts The American University in Cairo - Egypt Department of Sociology/Anthropology May 1989 Bachelors of Arts University of Arizona, Tucson - USA Middle Eastern Studies and French June 1986 Secondary School Certificate: Abitur Horkesgath Gymnasium, Krefeld - Germany Languages: Excellent English and German; Good Arabic and French 3. Career Record: January 2019 - Robert Family Professor of Middle East Studies Watson Institute for Policy and International Affairs & Department of Anthropology September 2010- Professor of Gender Studies December 2018 Centre for Gender Studies SOAS, University of London September 2008- Reader in Gender Studies August 2010 Chair, Centre for Gender Studies SOAS, University of London September 2007- Lecturer in Gender Studies August 2008 Centre for Gender Studies SOAS, University of London October 2005 - Senior Lecturer in Social Anthropology August 2007 The Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies The University of Exeter March 2000 - Lecturer in Social Anthropology Sept 2004 The Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies The University of Exeter March-July 2003 Visiting Professor in International Women’s Studies The University of Bochum, Germany 1 Oct. 1998 - Research Fellow Feb 2000 Sussex Centre for Migration Research University of Sussex 1996-1998 Teaching Fellow (GTA) School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1989-1993 Research and Teaching Assistant The American University in Cairo. -

Women in Islamic Societies: a Selected Review of Social Scientific Literature

WOMEN IN ISLAMIC SOCIETIES: A SELECTED REVIEW OF SOCIAL SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Office of the Director of National Intelligence/National Intelligence Council (ODNI/ADDNIA/NIC) and Central Intelligence Agency/Directorate of Science & Technology November 2005 Author: Priscilla Offenhauer Project Manager: Alice Buchalter Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax:202 −707 − 3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd p 57 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2005 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Women in Islamic Societies PREFACE Half a billion Muslim women inhabit some 45 Muslim-majority countries, and another 30 or more countries have significant Muslim minorities, including, increasingly, countries in the developed West. This study provides a literature review of recent empirical social science scholarship that addresses the actualities of women’s lives in Muslim societies across multiple geographic regions. The study seeks simultaneously to orient the reader in the available social scientific literature on the major dimensions of women’s lives and to present analyses of empirical findings that emerge from these bodies of literature. Because the scholarly literature on Muslim women has grown voluminous in the past two decades, this study is necessarily selective in its coverage. It highlights major works and representative studies in each of several subject areas and alerts the reader to additional significant research in lengthy footnotes. In order to handle a literature that has grown voluminous in the past two decades, the study includes an “Introduction” and a section on “The Scholarship on Women in Islamic Societies” that offer general observations⎯bird’s eye views⎯of the literature as a whole. -

Women and Gender in the Middle East and North Africa, WMST345-01/INTL200-01 Mondays and Wednesdays 2:30-3:50, Knapp Hall 409 Denison University, Fall 2007

Women and Gender in the Middle East and North Africa, WMST345-01/INTL200-01 Mondays and Wednesdays 2:30-3:50, Knapp Hall 409 Denison University, Fall 2007 Instructor: Isis Nusair Email: [email protected] Office: Knapp Hall 210C, Phone: (740) 587-8537 Office Hours: Mondays and Wednesdays 4:30-6 Course Description This course investigates contemporary feminist thinking and practice in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and provides students with the ability to understand, critique, and comparatively analyze the politics of gender in the MENA region. The class covers current debates on the status of women, and closely examines the processes by which the private/public lives of women are gendered. It addresses women's visibility in society and the development or lack thereof of women's and feminist movements. The main themes covered in the course include colonization, women and the state, citizenship, nationalism, religion, sexuality, representation, development, militarization, human rights, and women’s movements. The course focuses on the following countries: Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, and Saudi Arabia. The class is interdisciplinary and uses feminist pedagogy to challenge orientalist, monolithic, and Eurocentric notions of studying the region and particularly the status of women. It gives equal weight to theory and practice and draws on writings by local and global activists and theorists. Class Requirements Students in addition to reading the course material, attending screening sessions, and participating in class discussions will monitor at least one media outlet and trace the representation of women and gender in the Middle East and North Africa. -

Facts and Fantasies

Facts and Fantasies Facts and Fantasies Images of Istanbul Women in the 1920s By D. Fatma Türe Facts and Fantasies: Images of Istanbul Women in the 1920s By D. Fatma Türe This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by D. Fatma Türe All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7222-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7222-5 To my three nieces, Seray, Sergün and Ayris. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .............................................................................................. ix A Note on Transliteration ........................................................................... xi A Note on Turkish Pronunciation ............................................................. xiii Acknowledgements ................................................................................... xv Preface ..................................................................................................... xvii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Conceptual Framework Chapter One .............................................................................................. -

An Interview with Deniz Kandiyoti

Feminist Dissent The Pitfalls of Secularism in Turkey: An Interview with Deniz Kandiyoti Correspondence: feministdissent@ gmail.com Deniz Kandiyoti is Emeritus Professor of Development Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Her work on gender, development, nationalism, and Islam has been deeply influential within feminist studies, development studies and Middle Eastern studies. Her path-breaking essay ‘Bargaining with Patriarchy’ appeared in the journal Gender and Society in 1988. She is the author of Concubines, Sisters and Citizens: Identities and Social Transformation (1997) and the editor of Fragments of Culture: The Everyday Life of Modern Turkey (2002), Gendering the Middle East (1996), Women, Islam and the State (1991). Peer review: This article has been subject to a double blind peer review Feminist Dissent conducted this interview by email. process Feminist Dissent (FD): In the case of Turkey, you have previously written © Copyright: The Authors. This article is that ‘the secular-Islamic divide is of dubious utility from an analytic point issued under the terms of the Creative Commons of view’. But what is the historical resonance of this divide? Looking back Attribution Non- Commercial Share Alike now at the foundational moment of the Kemalist state in 1923, what do License, which permits use and redistribution of you think were the real possibilities then, if any, for an embedded, the work provided that the original author and democratically articulated secularism? source are credited, the work is not used for commercial purposes and Deniz Kandiyoti (DK): In order to fully understand the specific resonance that any derivative works are made available under of the secular-Islamic divide in Turkey it is necessary to look much further the same license terms. -

Middle Eastern Patriarchy in Transition

Middle Eastern PatriarchyDie Welt Indes Transition Islams 57 (2017) 265-277 265 International Journal for the Study of Modern Islam brill.com/wdi Middle Eastern Patriarchy in Transition Contents Middle Eastern Patriarchy in Transition 265 Rania Maktabi and Brynjar Lia (guest editors) Rania Maktabi and Brynjar Lia (guest editors) Broken Walls: Challenges to Patriarchal Authority in the Eyes of Sudanese Social Media Actors 278 University of Oslo Albrecht Hofheinz [email protected]; [email protected] Beyond Preaching Women: Saudi Dāʿiyāt and Their Engagement in the Public Sphere 303 Laila Makboul Islamist Women as Candidates in Elections: A Comparison of the Party of Justice and Development in Morocco and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt 329 Katarína Škrabáková Introduction Agents of Change: How Islamist Women Activists in Israel Are Challenging the Status Quo 360 Tilde Rosmer Nationalist Patriarchy, Clan Democracy: How the Political Trajectories of Palestinians in Israel and the Occupied Terri- In Gender and Citizenship in the Middle East (2000), twenty scholars coalesced tories Have Been Reversed 386 Dag H. Tuastad around a definition of patriarchy as a “system of social relations privileging Kurdish Women in Rojava: From Resistance to Reconstruction 404 Pinar Tank male seniors over juniors and women, both in the private and public spheres.”1 The Jihādī Movement and Rebel Governance: The all-woman scholarly choir presented nuanced approaches towards de- A Reassertion of a Patriarchal Order? 429 Brynjar Lia scribing, historicizing, and analysing the contained and mediated citizenship Reluctant Feminists? Islamist MP s and the Representation of Women in Kuwait after 2005 451 Rania Maktabi of youth and women in contemporary states in the Middle East and North Af- rica (MENA) region.