When Red Meets Green: Perceptions of Environmental Change in the B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kennebec Woodland Days 2016 Public Events That Recognize & Celebrate Our Forests

Kennebec Woodland Days 2016 Public Events that Recognize & Celebrate Our Forests Women and Our Woods – A Maine Outdoors Workshop WHEN: Saturday, October 15, 2016, 8:30 am -4:30 pm WHERE: Pine Tree Camp, Rome, Maine Women and our Woods is teaming up with Women of the Maine Outdoors to offer an action-packed workshop for women woodland owners and outdoor enthusiasts! Join us for engaging, hands-on classes in a variety of topics including forestry for the birds; Where in the woods are we?; Chainsaws: Safety First; & Wildlife Tracking. Participation limited, so please register soon! REGISTER: womenofthemeoutdoors.com. FMI: Amanda Mahaffey:207-432-3701 or [email protected] COST: $40. How to Plan for a Successful Timber Harvest – Waldoboro WHEN: Tuesday, October 18, 6:00-8:00 pm WHERE: Medomak Valley H.S., Waldoboro If timber harvesting is part of the long-range plan, how do you go about actually putting together a timber harvest? This session will talk about the steps landowners can take to prepare for a harvest and to make sure they get the results they want. We will discuss tree selection, types of harvests, access trails, equipment options, wood products, and communicating with foresters and loggers. REGISTER: Lincoln County Adult Education website; register and pay using a debit/credit card at: msad40.maineadulted.org OR clc.maineadulted.org. FMI: District Forester Morten Moesswilde at 441- 2895 [email protected] COST: Course Fee: $14 Family Forestry Days WHEN: Saturday, October 22, 1:30-3:30 pm WHERE: Curtis Homestead, Bog Road, Leeds The Kennebec Land Trust (KLT) invites you to Family Forestry Day: A Sustainable Forestry Education Program. -

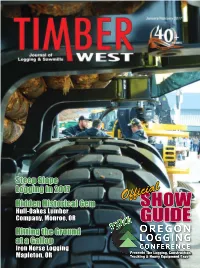

Show Guide a Comprehensive Listing of All the Events, Panels and Exhibitors of the 2017 OLC

Steep Slope Logging in 2017 Official Hidden Historical Gem SHOW Hull-Oakes Lumber Company, Monroe, OR GUIDE Hitting the Ground at a Gallop Iron Horse Logging Presents The Logging, Construction, Mapleton, OR Trucking & Heavy Equipment Expo ON THE COVER Photo taken at the 2016 Oregon Logging Conference January/February 2017 Vol. 42 No. 01-02 6 2017 OLC Show Guide A comprehensive listing of all the events, panels and exhibitors of the 2017 OLC. 2017 OLC Show Guide Breakfasts to Welcome Loggers ............................................. Page 15 Chainsaw Carving Event. ........................................................... Page 42 Dessert for Dreams ..................................................................... Page 22 Exhibitor’s List. .............................................................................. Page 58 Family Day. ..................................................................................... Page 38 Friday Night 79th Celebration Even ...................................... Page 20 Food Locations ............................................................................. Page 40 Guess the Net Board Feet ......................................................... Page 24 Keynote speaker. .......................................................................... Page 14 Log Loader Competition ........................................................... Page 54 MAP............. ...................................................................................... Page 48 Meet & Greet ................................................................................ -

Dick Campbell L E L-77398

u . - ----.-- o NOVEMBER. 1987 31756O OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF INTERNATION ALORDER OF HOO HOO THE FRATERNAI ORDER OF THE FOREST PRODUCTSINDSTRY s N A R K i 9 o 8 F 7 r I T i H 9 E 8 8 U N I V E R s DICK CAMPBELL L E L-77398 1- . ,, i ' ' . .. p \____ J I I_,& TIIt SI'S 3 I7 6C)) i. puhhhcd qLlirwrh I.'r VICE PRESIDENTS' REPORT S5.'9 per tear h he InftmaUo!laI Concatcnuitcd LOG & TALLY Order ,f Hc,Hoo. Iii. P 0. Ro II X . GElrdon. Ark. 71743, SecondCI; age paid at Gurdo,t. Ark.. NOVEMBER, 1988 VOLUME 97 NO I arid additional mili i TIF! ' POSTMASTER Send addrL hangesh. tor & FIRST VICE PRESIDENT will tive us an added dimensäon in communication through this TalI. P 0 B' II 8. (jurdon. Ark. 7 I 743 increasingly popular medium. Phil CocksL-77298 In 1992. Hoo-Hoowillbe 100 years old. Rameses Laurn Champ is heading up this project which will be held in Hot We want them. have Just returned from 2 weeksofHoo-Hooing whichSprings. Arkansas. Fund raising is already under way with a Our hard working Gurdon crew. Billy and Beth. will be included the International Convention in Seattle and a tour ofspecial $ I per member per year assessment. getting an updated computer for general procedures to continue the West Coast. the highlight of which was a visit to the Hoo- Attendees at this years convention in Seattle contributed the highly successful dues billing program. Communications Hoo Memorial Redwood Grove. near Eureka. -

A-Ac837e.Pdf

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The word “countries” appearing in the text refers to countries, territories and areas without distinction. The designations “developed” and “developing” countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. The opinions expressed in the articles by contributing authors are not necessarily those of FAO. The EC-FAO Partnership Programme on Information and Analysis for Sustainable Forest Management: Linking National and International Efforts in South Asia and Southeast Asia is designed to enhance country capacities to collect and analyze relevant data, to disseminate up-to- date information on forestry and to make this information more readily available for strategic decision-making. Thirteen countries in South and Southeast Asia (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Lao P.D.R., Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam) participate in the Programme. Operating under the guidance of the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission (APFC) Working Group on Statistics and Information, the initiative is implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in close partnership with experts from participating countries. It draws on experience gained from similar EC-FAO efforts in Africa, and the Caribbean and Latin America and is funded by the European Commission. -

Wood Industries Classifieds

Wood Industries Classifieds Cost of Classified Ads: $70 per column inch if paid in advance, Please note: The Northern Logger neither endorses nor makes $75 per column inch if billed thereafter. Repeating ads are any representation or guarantee as to the quality of goods or $65 per column inch if paid in advance, $70 per column inch if the accuracy of claims made by the advertisers appearing in billed thereafter. Firm deadline for ads is the 15th of the month this magazine. Prospective buyers are urged to take normal preceding publication. To place an ad call (315) 369-3078; FAX precautions when conducting business with firms advertising (315) 369-3736. goods and services herein. THE NORTHERN LOGGER | JULY 2018 35 FOR SALE 2004 John Deere 640GIII Cable Skidder. Remanufactured engine, very good condition, new chains all around, new rear tires, owner/ operator $54,000. 603-481-1377 SHAVINGS MILL 30” Salsco Shavings Mill with blower. CAT diesel motor with only 2950 hrs. 8’ x 30” box. Trailer mounted. Excellent condition. Inventory of pine pulp included. $29,000 or best offer 603-876-4624 2006 425EXL Timbco Feller Buncher, 8000 hours, purchased new, well maintained. KLEIS EQUIPMENT LLC 2002 Komatsu 228 (PC228USLC-3) 2008 TimberPro TN725B with Rolly II, Many Excavator, 400HP JD power pack, with New Parts .........................................$175,000 Shinn stump grinder with bucktooth 2015 CAT 525D Dual Arch Grapple, Winch, wheel, 16000 hours, purchased new, Double Diamonds All Around ............$119,000 2005 Deere 748GIII Dual Arch Grapple Skidder, well maintained. More photos at www. New Deere Complete Engine ............. $65,000 edwardslandclearingandtreeservice.com 2013 Deere 648H, DD, Dual Arch, Winch, 24.5 Rubber, 5000 Hours .........................$135,000 Edwards Landclearing 2003 Deere 648GIII Single Arch, 28L Rubber, 216-244-4413 or 216-244-4450 Winch ................................................ -

Outdoor-Industry Jobs a Ground Level Look at Opportunities in the Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Outdoor Recreation Sectors

Outdoor-Industry Jobs A Ground Level Look at Opportunities in the Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Outdoor Recreation Sectors Written by: Dave Wallace, Research Director, Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board Chris Dula, Research Investigator, Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board Randy Smith, IT and Research Specialist, Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board Alan Hardcastle, Senior Research Manager, WSU Energy Program, Washington State University James Richard McCall, Research Assistant, Social and Economic Sciences Research Center (SESRC), Washington State University Thom Allen, Project Manager, Social and Economic Sciences Research Center (SESRC), Washington State University Executive Summary Washington’s Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board (Workforce Board) was tasked by the Legislature to conduct a comprehensive study1 centered on outdoor and field-based employment2 in Washington, which includes a wide range of jobs in the environment, agriculture, natural resources, and outdoor recreation sectors. Certainly, outdoor jobs abound in Washington, with our state’s Understating often has inspiring mountains and beaches, fertile and productive farmland, the effect of undervaluing abundant natural resources, and highly valued natural environment. these jobs and skills, But the existing data does not provide a full picture of the demand for which can mean missed these jobs, nor the skills required to fill them. opportunities for Washington’s workers Digging deeper into existing data and surveying employers in these and employers. sectors could help pinpoint opportunities for Washington’s young people to enter these sectors and find fulfilling careers. This study was intended to assess current—and projected—employment levels across these sectors with a particular focus on science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) oriented occupations that require “mid-level” education and skills. -

Spruce and Pine on Drained Peatlands Wood Quality

HELSINGIN YLIOPISTON METSÄVAROJEN KÄYTÖN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA 35 UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI DEPARTMENT OF FOREST RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PUBLICATIONS 35 SPRUCE AND PINE ON DRAINED PEATLANDS WOOD QUALITY AND SUITABILITY FOR THE SAWMILL INDUSTRY Juha Rikala To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Helsinki, for public critisism in the Auditorium B2, Latokartanonkaari 9 A, Helsinki, on 21 November 2003, at 12 o´clock noon. Helsinki 2003 Opponent: Professor Torbjörn Elowson Department of Forest Products and Markets Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden Reviewers: Professor Matti Kärkkäinen Sepetlahdentie 7 A 21 FIN-02230 Espoo, Finland Professor Mats Nylinder Department of Forest Products and Markets Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden Supervisor: Professor Marketta Sipi Department of Forest Resource Management FIN-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Revision of English: Carol Pelli Language Center FIN-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Cover: Upper left: Mature spruces on Herb-rich type, Jaakkoinsuo, Municipality of Vilppula Upper right: Mature pines on Vaccinium vitis-idaea type, Ruotsinkylä, Municipality of Tuusula Lower left: A felled spruce stem cut into logs. Sample discs were taken for wood property studies. Lower right: Sawn pieces on conveyor, Pori College of Forestry, Municipality of Kullaa (Photos: Juha Rikala) ISBN 951-45-9091-0 (paperback) ISBN 951-45-9092-9 (pdf) ISSN 1236-1313 Helsinki 2003 Yliopistopaino Rikala, J. 2003. Spruce and pine on drained peatlands ʊ wood quality and suitability for the sawmill industry. University of Helsinki, Department of Forest Resource Management, Publications 35. 147 p. ABSTRACT Drained peatlands are a characteristic specific to Finnish forestry. -

NW Woodlands-Spring 2001

SPRING 2012 • VOLUME 28 • NO. 2 NAN Publicationoo of rther Oregontth hSmall Woodlands,wwee Washingtonsstt FarmW WForestry, Idahooo Forestoo Ownersdd & Montanallaa Forestnn Ownersdd Associationsss MARKETSMMARKETSARKETS GlobalGGloballobal ForestFForestorest ProductsPProductsroducts MarketsMMarketsarkets DecipheringDDecipheringeciphering ForestFForestorest ProductsPProductsroducts MarketMMarketarket TTrendsrendsrends WhatWWhathat YYououou ShouldSShouldhould KnowKKnownow aboutaaboutbout thetthehe ExportEExportxport MarketMMarketarket MarketingMMarketingarketing LogsLLogsogs CaveatsCCaveatsaveats HousingHHousingousing OutlookOOutlookutlook NEXT ISSUE . Management Plans PERMIT NO. 1386 NO. PERMIT TLAND, OR TLAND, POR AID P Portland, OR 97221 OR Portland, U.S. POSTAGE U.S. 4033 S.W. Canyon Rd. Canyon S.W. 4033 Non Profit Org Profit Non Northwest Woodlands Northwest This magazine is a benefit of membership in your family forestry association TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 3 PRESIDENTS’ MESSAGES Spring 2012 6 DOWN ON THE TREE FARM FEATURES 26 CALENDAR GLOBAL FOREST PRODUCTS MARKETS: IMPACTS ON 28 TREESMARTS FAMILY FOREST OWNERS 30 TREEMAN TIPS Changes to the global forest industry have resulted in shifts in demand for North American forest products. What’s in store for Northwest family ON THE COVER: forest owners? 8 BY CHRIS KNOWLES AND ERIC HANSEN DECIPHERING FOREST PRODUCTS MARKET TRENDS IN OREGON, WASHINGTON, IDAHO AND MONTANA A stalled housing market, the Great Recession, and a robust export market are just a few factors that have affected local harvest levels, lumber production, and employment in the Northwest. 12 BY XIAOPING ZHOU AND RACHEL WHITE A ship gets loaded with logs at the Port of Port Angeles in WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT THE LOG EXPORT Washington. Photo courtesy of Susheen Timber Trading. MARKET With a booming export market, find out if your trees have what it takes. -

Occupational Orientation: Applied Biological and Agricultural Occupations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 130 116 CE 008 638 TITLE Occupational Orientation: Applied Biological and Agricultural Occupations. Experimental Curriculum Materials. INSTITUTION Illinois State Office of Education, Springfield. PUB DATE [75] NOTE 178p.; For related documents see CE 008 635-639 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$10.03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Activity Learning; Agribusiness; Agricultural Machinery Occupations; *Agricultural Occupations; Agricultural Production; Attitude Tests; *Biological Sciences; *Career Exploration; *Conservation (Environment); Criterion Referenced Tests; Curriculum; Environment; Farm Mechanics (Occupation) ; Forestry Occupations; Horticulture; Instructional Materials; *Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; Natural Resources; *Occupational Clusters; Occupational Guidance; Performance Based Education; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS Illinois ABSTRACT These experimental curriculum materials, from one of five clusters developed for the occupational orientation program in Illinois, include a series of learning activity packages (LAPs) designed to acquaint the student with the wide range of occupational choices available in the applied biological and agricultural occupations. The 30 LAPs, each with a different occupation focus are grouped under six categories:(1) Applied Biological and Agricultural Occupations,(2) Agricultural Mechanics,(3) Agricultural Products, Supplies, Sales, and Services,(4) Natural Resources, Forestry, and Environmental Control, (5) Ornamental Horticulture, and (6) Production Agriculture. Each LAP identifies -

Timber Sale Planning and Forest Products Marketing

Timber Sale Planning and Forest Products Marketing: A Guide for Montana Landowners Roy C. Anderson Montana State University Forest Products Marketing Specialist Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 Forest Management Planning ......................................................................................... 3 Forest management plan components ........................................................................ 3 1. Property Description............................................................................................ 3 2. Management Goals and Objectives .................................................................... 4 3. Schedule Management Activities ........................................................................ 4 Forest management planning assistance .................................................................... 4 Timber Sale Planning...................................................................................................... 6 Steps in the timber sale process.................................................................................. 6 1. Seek assistance from a professional forester ..................................................... 6 2. Mark property & sale boundaries ........................................................................ 7 3. Mark the trees to be harvested............................................................................ 8 4. Estimate -

The Port Gamble Redevelopment Plan Sepa Eis, Kitsap County, Washington

TECHNICAL REPORT OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD INVESTIGATIONS TO SUPPORT THE PORT GAMBLE REDEVELOPMENT PLAN SEPA EIS, KITSAP COUNTY, WASHINGTON REDACTED May 30, 2018 SWCA Project Number 24888.02 SWCA Report Number 14-19 SWCA ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANTS SEATTLE, WASHINGTON TECHNICAL REPORT OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD INVESTIGATIONS TO SUPPORT THE PORT GAMBLE REDEVELOPMENT PLAN SEPA EIS, KITSAP COUNTY, WASHINGTON Report Prepared for Olympic Property Group 19950 7th Avenue NE, Suite 200 Poulsbo, WA 98370 By Brandy Rinck, Alicia Valentino, Christian Miss, Amber Earley, and Mike Cannon May 30, 2018 SWCA Project Number 24888.02 SWCA Report Number 14-19 REDACTED SWCA Environmental Consultants 221 1st Ave W, Suite 205 Seattle, Washington 98119 ABSTRACT This report presents the methods and results of archaeological fieldwork completed to support the discipline report for archaeology for the Port Gamble Redevelopment Plan State Environmental Protection Act (SEPA) Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) (Piper et al. 2014). Archaeological fieldwork consisted of pedestrian survey, shovel probe excavation, magnetometer survey, completion of geotechnical cores, and mechanical test pit excavation. Six archaeological sites and one isolate were recorded during fieldwork. These include 45KP252 (Pre‐contact Shell Midden), 45KP253 ( Historic Dump), 45KP254 (Babcock Dairy and Port Gamble Dance House), 45KP255 (Port Gamble Chinese Laundry and Residences), 45KP256 (Port Gamble Workers Housing Debris Scatter), 45KP257 (an isolated historic bottle base), and 45KP258 ( Culturally‐Modified Cedars). In addition, probable historical debris was identified in many of the excavations. Sites 45KP252 (Pre‐contact Shell Midden), 45KP254 (Babcock Dairy and Port Gamble Dance House), 45KP255 (Port Gamble Chinese Laundry and Residences), 45KP256 (Port Gamble Workers Housing Debris Scatter), and 45KP258 ( Culturally‐Modified Cedars) are recommended eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). -

Careers in Oregon's Forest Sector

Careers in Oregon’s Forest Sector Volume 2: Options for High School Graduates Careers in Oregon’s forest and wood products manufacturing operations offer exciting opportunities to learn and apply a wide range of skills in a variety of indoor and outdoor settings. These rewarding careers not only deliver valuable wood products to The Oregon Legislature created the Oregon Forest the market, they help ensure the continued Resources Institute (OFRI) in 1991 to improve public protection of Oregon’s environment. Ever understanding of forests, forest products and forest advancing technology and innovation help management and to encourage sound forestry through people in this field do things better, safer landowner training. In keeping with this mission, and in more comfortable settings than ever OFRI sponsors classroom and field programs for K-12 students and teachers and produces educational before. materials such as this publication. This publication is a guide for high school students looking for satisfying careers that do not require a college degree. It examines careers in the production of wood products – from the growing and harvesting of timber to the transport and delivery of logs to the mill and the manufacturing of products made from trees. Students may gain useful insights from reading about the people profiled in this publication and about their job duties, required skills, working conditions and career paths. There are additional information sources and Web sites about forest operations and manufacturing careers (on the back cover). This is Volume 2 of two publications that OFRI offers for use by high school students seeking information on career opportunities in Oregon’s forest sector.