Grandfather of Wader Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Portsmouth Number List

Historical Portsmouth Number List The RYA Portsmouth Yardstick Scheme is provided to enable clubs to allow boats of different classes to race against each other fairly. The RYA actively encourages clubs to adjust handicaps where classes are either under or over performing compared to the number being used. The Portsmouth Yardstick list combines the Portsmouth numbers with class configuration and the total number of races returned to the RYA in the annual return. This additional data has been provided to help clubs achieve the stated aims of the Portsmouth Yardstick system and make adjustments to Portsmouth Numbers where necessary. Clubs using the PN list should be aware that the list is based on the average performance of each boat across a variety of clubs and locations. The numbers in the PN list may not reflect the peak performance of each boat. Historical numbers are listed below and have been collated from the RYA's archive of PN lists. It should be remembered that the Portsmouth Yardstick number list has been through a number of changes and the numbers listed below have had conversion factors applied where needed. It should also be remembered that whilst all efforts are taken for PN's not to drift, relative performance of older boats may be quite different to modern classes. The numbers are given as a starting point to help clubs arrive at a fair number and if these numbers are used then they should be reviewed regularly. Users of the PY scheme are reminded that all Portsmouth Numbers published by the RYA should be regarded as a guide only. -

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research Through a History of Aardman Animations

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive | Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive: Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Adrian All rights reserved. Cover image: BTS19_rgb - TM &2005 DreamWorks Animation SKG and TM Aardman Animations Ltd. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Performance Studies at Utrecht University. Author Rebecca A. E. E. Adrian Student number 4117379 Thesis supervisor Judith Keilbach Second reader Frank Kessler Date 17 August 2018 Contents Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 1 // Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.1 | Lack of Histories of Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.2 | Marketing, Glocalisation and the Success of Aardman 7 1.3 | The Influence of the British Television Landscape 10 2 // Digital Archival Research 12 2.1 | Digital Surrogates in Archival Research 12 2.2 | Authenticity versus Accessibility 13 2.3 | Expanded Excavation and Search Limitations 14 2.4 | Prestige of Substance or Form 14 2.5 | Critical Engagement 15 3 // A History of Aardman in the British Television Landscape 18 3.1 | Aardman’s Origins and Children’s TV in the 1970s 18 3.1.1 | A Changing Attitude towards Television 19 3.2 | Animated Shorts and Channel 4 in the 1980s 20 3.2.1 | Broadcasting Act 1980 20 3.2.2 | Aardman and Channel -

Speakers Discuss of School Money The

Vol. X I. No. 44 OCEAN GROVE, NEW JERSEY, SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31, 1903. One Dollar the Y ear. PREACHERS’ MEETINGS A. SOCIAL EVENT OF DANIEL W. APPLEGATE SPEAKERS DISCUSS THIS WEEK AND NEXT THE LATE FALL SEASON WEDS MISS ANNA REED Local Clergymen Will Go: to Freehold OF SCHOOL MONEY Mr, and Mrs. Carr Celebrate the An THE STATUE FUND Their Marriage Followed by Sere the .Coming Maaday .. y ; niversary of Their Wedding nade and Surprise Party FINAL POLITICAL MEETING BE At the preachers’ meeting in St. RECENT LAW MAKES TOWNSHIP. Mastering every detail that would M ATTER IN HANDS OF THE STOKES’ Daniel W. Applegate and Miss Anna .Paul’s church, Ocean Grove, on Mon contribute In any wise to the pleasure Reed, both of Ocean Grove, were’mar- . FORE FALL ELECTION day morning, tit. exercises- were TREASURER THAT OFFICER of tileir guests, Mr.. .and Mrs. R. H. ,; " FINANCE COMMITTEE ried on Sunday last at the parsonage opened with prayer by the Rev. W. W. Carr,' of Brooklyn, celebrated their of the Hamilton M. E. Church by tho. RIdgely, o£ West Park. On the sail wedding anniversary last Saturday Rev. W. E. Blackiston/ The bride is <jf committees the Rev H. Jt .Hayter, evening a t their Biimmer .home, 79 Pil the daughter of Mr. and Mrs, Aaron. ALL OVER BUT SHOUTING of Bradley Beach, read on article TRUSTEE BittDNER IS OUT grim Pathway. In attendance at this NOW ALL WAY CONTRIBUTE Reed, of 119 Abbott avenue. Mr. Ap showing the agitation of the Temper event were Mrs. M. -

Razzle Dazzle Camouflage – Was It Effective?

Razzle Dazzle Camouflage – Was it effective? By Geoff Walker The British have always been very innovative in conducting warfare, especially when it involved “Camouflage” both ashore and afloat. “Dazzle Camouflage” was just one of those many innovations. It consisted of complex patterns and geometric shapes in contrasting colors, interrupting, and intersecting, each other. It was not limited to just “Black and White”, but often multiple colors were introduced into the patterns. “HMS Belfast” at her London moorings Unknown photographer British Artist and naval officer, Norman Wilkinson had this very insight and is accredited with pioneering the Dazzle Camouflage system - known as Razzle Dazzle in the United States. Wilkinson used bright, loud colors and contrasting diagonal stripes to make it incredibly difficult to gauge a ship’s size and direction. How to camouflage ships at sea was one of the big questions of World War I. From the early stages of the war, artists, naturalists, and inventors showered the offices of the British Royal Navy with largely impractical suggestions on making ships less visible, or difficult to define. Wilkinson’s innovation, what would be called “Dazzle”, was rather than using camouflage to hide the vessel, he used it to hide the vessel’s intention. Later he’d say that he’d realized, “Since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer – in other words, to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as the course on which she was heading.” Wilkinson used broad stripes and polygons of contrasting colors—black and white, green, and mauve, orange, and blue—in geometric shapes and curves to make it difficult to determine the ship’s actual shape, size, and direction. -

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM and MYSTICISM in AMERICAN NATURE WRITING by DAVID TAGNANI a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfill

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING By DAVID TAGNANI A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2015 © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of DAVID TAGNANI find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________________ Christopher Arigo, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________________ Donna Campbell, Ph.D. ___________________________________________ Jon Hegglund, Ph.D. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my committee members for their hard work guiding and encouraging this project. Chris Arigo’s passion for the subject and familiarity with arcane source material were invaluable in pushing me forward. Donna Campbell’s challenging questions and encyclopedic knowledge helped shore up weak points throughout. Jon Hegglund has my gratitude for agreeing to join this committee at the last minute. Former committee member Augusta Rohrbach also deserves acknowledgement, as her hard work led to significant restructuring and important theoretical insights. Finally, this project would have been impossible without my wife Angela, who worked hard to ensure I had the time and space to complete this project. iv ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING Abstract by David Tagnani, Ph.D. Washington State University May 2015 Chair: Christopher Arigo This dissertation investigates the ways in which a theory of material mysticism can help us understand and synthesize two important trends in the American nature writing—mysticism and materialism. -

Abbotsford Sailing Club News 0 7/04/2021 Wrap-Up of the 85Th 12Ft Skiff Australian Championships

Abbotsford Sailing Club News 07/04/2021 Wrap-up of the 85th 12Ft skiff Australian Championships It was an extremely lively Easter weekend at the club with all the 12ft skiff crews visiting, the racing and the dinners and socialising after the racing. The whole event was a great success, we had enough breeze to complete all the races, and the last day even offered a bit more spectacle, after some lighter days earlier in the weekend. All results, photos and videos are on our regatta page. A thank you to all the crews who participated and the 1 2ft skiff association for choosing Abbotsford for this regatta. As the president of the club, I really would like to thank all the members, friends, family and past members who helped out at the club, including the bar and canteen and the support on the water. A special thank you to Robyn and Barrie who, together with Judy, ran all the starts and finishes from Scout. A major effort and much appreciated! We will have those snacks and drinks ready for next time you are able to officiate! Also a big thank you to Tom Biskupic for being the on-shore race manager and race recorder, and keeping the race results up to date on the website. I also wanted to thank all our generous sponsors, whose support has helped make this regatta a great success. Please check out t he list on the regatta page. Last but not least, I would like to thank the Regatta committee and in particular Peter and Lisa Hill and Gai Dewane, for doing the majority of the organising. -

2015-2016 Cherub Nationals Sailing Instructions

53rd Australian Cherub Championship Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron, Brisbane, QLD 28th December 2015 to 3rd January 2016 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS The 53rd Australian Cherub Championships will be conducted on Waterloo Bay, Brisbane, Queensland from 28th December 2015 to 3rd January 2016 inclusive. The Organising Authority will be the Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron Inc. (RQYS) on behalf of the Cherub Class Owners Association of Queensland. 1. RULES 1.1 The regatta will be governed by the rules as defined in: (a) The Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS), (b) The Prescriptions and Special Regulations of Yachting Australia, (c) The 53rd Australian Cherub Championships Sailing Instructions, (d) The Cherub National Council of Australia Constitution and By-laws (found on the national website www.cherub.org.au or by contacting the National Secretary). 2. NOTICES TO COMPETITORS Notices to competitors will be posted on the official notice board located on the rigging lawn adjacent to the RQYS Sailing Office. 3. CHANGES TO SAILING INSTRUCTIONS Any changes to the Sailing Instructions will be posted not less than ninety (90) minutes before the next scheduled start, except that any change in the schedule of races will be posted by 1900 hours on the day before it will take effect. 4. ADVERTISING The Cherub class is classed as Category “A” in accordance with the ISAF Regulation 20.4.1. Competitors may be required to carry event sponsors’ stickers as set out in the Sailing Instructions and may, at the discretion of the organising authority, be required to remove any other advertising the organising authority considers to be inappropriate. -

2020 Zephyr & 12 Foot Skiff Auckland Championships

Organizing Authority: Postal Address: French Bay Yacht Club, French Bay Yacht Club Otitori Bay Road, PO Box 60-012, Titirangi, Titirangi Auckland Email: Web: [email protected] www.frenchbay.org.nz 2020 ZEPHYR & 12 FOOT SKIFF AUCKLAND CHAMPIONSHIPS Saturday 3rd & Sunday 4th October 2020 The Organising Authority is: French Bay Yacht Club Inc., Titirangi, Auckland NOTICE OF RACE 1 RULES 1.1 The regatta will be governed by the rules as defined in The Racing Rules of Sailing 2017-2020. 1.2 The Yachting New Zealand Safety Regulations Part 1 shall apply. 1.3 The sailing instructions will consist of the instructions in RRS Appendix S, Standard Sailing Instructions, and supplementary sailing instructions that will be available at registration and on the official notice board located at French Bay Yacht Club. 1.4 RRS 31 - Touching a Mark is deleted. This change will appear in full in the supplementary sailing instructions: 1.5 Appendix T, Arbitration, will apply. 2 ADVERTISING Boats may be required to display advertising chosen and supplied by the organising authority in accordance with World Sailing Regulation 20, Advertising Code. 3 ELIGIBILITY AND ENTRY 3.1 The regatta is open to boats of the Zephyr and 12ft Skiff Classes. 3.2 Competitors must be a financial member of a Club affiliated to a National Authority. 3.3 Eligible boats must be compliant with the rules of their Class Association. Organizing Authority: Postal Address: French Bay Yacht Club, French Bay Yacht Club Otitori Bay Road, PO Box 60-012, Titirangi, Titirangi Auckland Email: Web: [email protected] www.frenchbay.org.nz 3.4 Eligible boats may enter online at: FBYC Online or by completing the entry form available at registration on Saturday 3rd October 2020. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Catalyst N05 Jul 200

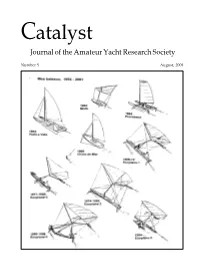

Catalyst Journal of the Amateur Yacht Research Society Number 5 August, 2001 Catalyst News and Views 3 Winds of Change 2001 6 Keiper Foils 7 Letters Features 10 Wind Profiles and Yacht Sails Mike Brettle 19 Remarks on Hydrofoil Sailboats Didier Costes 26 Designing Racing Dinghies Part 2 Jim Champ 29 Rotors Revisited Joe Norwood Notes from Toad Hill 33 A Laminar Flow Propulsion System Frank Bailey 36 Catalyst Calendar On the Cover Didier Costes boats (See page 19) AUGUST 2001 1 Catalyst Meginhufers and other antiquities I spent most of July in Norway, chasing the midnight sun Journal of the and in passing spending a fair amount of time in Norway’s Amateur Yacht Research Society maritime museums looking at the development history of the smaller Viking boats. Editorial Team — Now as most AYRS members will know, the Vikings rowed Simon Fishwick and sailed their boats and themselves over all of Northern Sheila Fishwick Europe, and as far away as Newfoundland to the west and Russia and Constantinople to the east. Viking boats were Dave Culp lapstrake built, held together with wooden pegs or rivets. Specialist Correspondents Originally just a skin with ribs, and thwarts at “gunwale” level, th Aerodynamics—Tom Speer by the 9 century AD they had gained a “second layer” of ribs Electronics—David Jolly and upper planking, and the original thwarts served as beams Human & Solar Power—Theo Schmidt under the decks. Which brings us to the meginhufer. Hydrofoils—George Chapman I’m told this term literally means “the strong plank”, and is Instrumentation—Joddy Chapman applied to what was once the top strake of the “lower boat”. -

Portsmouth Number List 2019

Portsmouth Number List 2019 The RYA Portsmouth Yardstick Scheme is provided to enable clubs to allow boats of different classes to race against each other fairly. The RYA actively encourages clubs to adjust handicaps where classes are either under or over performing compared to the number being used. The Portsmouth Yardstick list combines the Portsmouth numbers with class configuration and the total number of races returned to the RYA in the annual return. This additional data has been provided to help clubs achieve the stated aims of the Portsmouth Yardstick system and make adjustments to Portsmouth Numbers where necessary. Clubs using the PN list should be aware that the list is based on the typical performance of each boat across a variety of clubs and locations. Experimental numbers are based on fewer returns and are to be used as a guide for clubs to allocate as a starting number before reviewing and adjusting where necessary. The list of experimental Portsmouth Numbers will be periodically reviewed by the RYA and is based on data received via PY Online. Users of the PY scheme are reminded that all Portsmouth Numbers published by the RYA should be regarded as a guide only. The RYA list is not definitive and clubs should adjust where necessary. For further information please visit the RYA website: http://www.rya.org.uk/racing/Pages/portsmouthyardstick.aspx RYA PN LIST - Dinghy No. of Change Class Name Rig Spinnaker Number Races Notes Crew from '18 420 2 S C 1111 0 428 2000 2 S A 1112 3 2242 29ER 2 S A 907 -5 277 505 2 S C 903 0 277 -

Quaker Values and Arts and Crafts Principles Pamela

THE BRYNMAWR EXPERIMENT 1928-1940 QUAKER VALUES AND ARTS AND CRAFTS PRINCIPLES by PAMELA MANAS SEH A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degreeof DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Faculty of Art and Design University College, Falmouth October, 2009 2 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. PAMELA MANASSEH THE BRYNMAWR EXPERIMENT, 1928-1940: QUAKER VALUES AND ARTS AND CRAFTS PRINCIPLES ABSTRACT This is a study of the social work of Quakers in the town of Brynmawr in South Wales during the depressions of the 1920s and 1930s. The work, which took place during the years 1928 to 1940, has become known as the Brynmawr Experiment. The initial provision of practical and financial relief for a town suffering severely from the effects of unemployment, was developed with the establishment of craft workshops to provide employment. Special reference is made to the furniture making workshop and the personnel involved with it. The thesis attempts to trace links between the moral and aesthetic values of Quakerism and the Arts and Crafts Movement and explores the extent to which the guiding principles of the social witness project and the furniture making enterprise resemble those of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the inter-war years, 1919-1939. All aspectsof the Quaker work at Brynmawr were prompted by concern for social justice and upholding the dignity of eachindividual.