An Ambivalent Ground: Re-Placing Australian Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran's Evolving Military Forces

CSIS_______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775-3270 To download further data: CSIS.ORG To contact author: [email protected] Iran's Evolving Military Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy July 2004 Copyright Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. Cordesman: Iran's Military forces 7/15/2004 Page ii Table of Contents I. IRAN AND THE GULF MILITARY BALANCE: THE “FOUR CORNERED” BALANCING ACT..........1 The Dynamics of the Gulf Military Balance ..........................................................................................................1 DEVELOPMENTS IN THE NORTH GULF ........................................................................................................................2 II. IRAN’S ERRATIC MILITARY MODERNIZATION.......................................................................................9 THE IRANIAN ARMY ...................................................................................................................................................9 THE ISLAMIC REVOLUTIONARY GUARDS CORPS (PASDARAN).................................................................................14 THE QUDS (QODS) FORCES ......................................................................................................................................15 THE BASIJ AND OTHER PARAMILITARY FORCES ......................................................................................................15 THE IRANIAN -

Irish Institute of Legal Executives Has Given Its Edition of “The Brief”, Then Please Feel Free to Send Hall Endorsement

H R F TThe OfficialTThe OfficialH Journal Journale ofe the of IrishtheB IrishB Institute InstituteR of ie Legalof ieLegal Executives ExecutivesF 2011 Issue2015 IN THiS ISSue... IILEX PROFILE: The new Minister for Justice, Equality and Defence; MR ALAN SHATTER TD Plus... Remembering Christine Smith The Office of Notary Public in Ireland A History of the Women’s Refuge in Rathmines Spotlight on Cork City Hall ElementsIn this Issue of. Pro-active Plus . Diane Burleigh becomes a Patron The Innocence Project CriminalFrances Fitzgerald Justice Profile Brighwater Salary Scales The Companies Act Griffith College Conferring - Dublin & Cork A Day in the Life of a Legal ExecutiveIILEX | The Brief 2015 1 in the Public Service 2011 Brief.indd 1 13/08/2011 10:41:35 THe BRieF 2015 TThe OfficialH Journale of the IrishB InstituteR of ieLegal ExecutivesF 2011 Issue CONTENTS Page Page N MessageH S fromSS the President... 3 The Companies Act 2014 10 I TClosei Encounters I ue Down Under 3 Appointment of Patron of IILEX Mrs. Diane Burleigh O.B.E. 12 Frances Fitzgerald - Profile 4 IILEX PROFILE: Salary Survey 2015 13 My Experience at Studying Law in Griffith The newCollege Minister Dublin for 5 Why not qualify as a Mediator? 14 Justice,The AIBEquality Private Bankingand Irish Law Awards 2015 5 Cork Conferring Ceremony 15 Defence;Marie McSweeney, Legal Executive of the Criminalising Contagion 16 Year 2014 - Irish Law Awards 2014 7 MR ALAN SHATTER TD Irish Convict Garret Cotter 18 Eu Treaty Rights - (Free Movement Rights) 7 Irish Innocence Project 20 Commissioner... for Oaths 8 Plus Frank Crummey FIILEX - Brief Profile 23 RememberingGriffith College Conferring Ceremony 9 Christine Smith Legal Disclaimer EDITORIAL TEAM The Brief adopts an independent and inquiring We the Editorial team hereby extend many thanks approach towards the law and the legal profession. -

Speakers Discuss of School Money The

Vol. X I. No. 44 OCEAN GROVE, NEW JERSEY, SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31, 1903. One Dollar the Y ear. PREACHERS’ MEETINGS A. SOCIAL EVENT OF DANIEL W. APPLEGATE SPEAKERS DISCUSS THIS WEEK AND NEXT THE LATE FALL SEASON WEDS MISS ANNA REED Local Clergymen Will Go: to Freehold OF SCHOOL MONEY Mr, and Mrs. Carr Celebrate the An THE STATUE FUND Their Marriage Followed by Sere the .Coming Maaday .. y ; niversary of Their Wedding nade and Surprise Party FINAL POLITICAL MEETING BE At the preachers’ meeting in St. RECENT LAW MAKES TOWNSHIP. Mastering every detail that would M ATTER IN HANDS OF THE STOKES’ Daniel W. Applegate and Miss Anna .Paul’s church, Ocean Grove, on Mon contribute In any wise to the pleasure Reed, both of Ocean Grove, were’mar- . FORE FALL ELECTION day morning, tit. exercises- were TREASURER THAT OFFICER of tileir guests, Mr.. .and Mrs. R. H. ,; " FINANCE COMMITTEE ried on Sunday last at the parsonage opened with prayer by the Rev. W. W. Carr,' of Brooklyn, celebrated their of the Hamilton M. E. Church by tho. RIdgely, o£ West Park. On the sail wedding anniversary last Saturday Rev. W. E. Blackiston/ The bride is <jf committees the Rev H. Jt .Hayter, evening a t their Biimmer .home, 79 Pil the daughter of Mr. and Mrs, Aaron. ALL OVER BUT SHOUTING of Bradley Beach, read on article TRUSTEE BittDNER IS OUT grim Pathway. In attendance at this NOW ALL WAY CONTRIBUTE Reed, of 119 Abbott avenue. Mr. Ap showing the agitation of the Temper event were Mrs. M. -

2015-2016 Cherub Nationals Sailing Instructions

53rd Australian Cherub Championship Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron, Brisbane, QLD 28th December 2015 to 3rd January 2016 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS The 53rd Australian Cherub Championships will be conducted on Waterloo Bay, Brisbane, Queensland from 28th December 2015 to 3rd January 2016 inclusive. The Organising Authority will be the Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron Inc. (RQYS) on behalf of the Cherub Class Owners Association of Queensland. 1. RULES 1.1 The regatta will be governed by the rules as defined in: (a) The Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS), (b) The Prescriptions and Special Regulations of Yachting Australia, (c) The 53rd Australian Cherub Championships Sailing Instructions, (d) The Cherub National Council of Australia Constitution and By-laws (found on the national website www.cherub.org.au or by contacting the National Secretary). 2. NOTICES TO COMPETITORS Notices to competitors will be posted on the official notice board located on the rigging lawn adjacent to the RQYS Sailing Office. 3. CHANGES TO SAILING INSTRUCTIONS Any changes to the Sailing Instructions will be posted not less than ninety (90) minutes before the next scheduled start, except that any change in the schedule of races will be posted by 1900 hours on the day before it will take effect. 4. ADVERTISING The Cherub class is classed as Category “A” in accordance with the ISAF Regulation 20.4.1. Competitors may be required to carry event sponsors’ stickers as set out in the Sailing Instructions and may, at the discretion of the organising authority, be required to remove any other advertising the organising authority considers to be inappropriate. -

Intercom-2019-06

The Intercom MEMBER Official Newsletter of the Interlake Sailing Class Association www.interlakesailing.org June 2019 Fall Sailing Just for fun… The Intercom 2 From the President By Terry Kilpatrick By the end of July, we will be half way through the 2019 Travelers’ Series regattas. This past winter and spring have brought record rainfall and the highest Lake Erie levels since the 1920s. As a result, even getting on the water has been an effort. Bob Sagan stepped down from the ISCA Marketing Vice President position in December of 2018. He has devoted 15+ years on the board and wants to sail with his daughter more before she grows up. Michigan Fleet 38 has hosted national championships in 2015, 2009, and 2001. Bob designed banners for events and signs which have been used at boat shows and regattas. He was instrumental getting the Interlake in the finals of the Sears Junior Championships in 2014. Bob has always been the “go to” guy at Traverse City. I will look forward to his stimulating phone calls. Nationals ~ July 24 – 27, 2019 As president, I am appointing a new Marketing Vice President, Cara Sanderson Bown. Cara has professional Registration is OPEN – register at experience in marketing and other one-design classes. https://www.yachtscoring.com/emenu.cfm?eID=9545 Please welcome Cara to the board. Proposed 2019-2020 ISCA Slate of Officers What’s Inside Thane Morgan President 3 From the President Dan Olsen Vice President 3 2019-20 ISCA Slate of Officers Tom Humphrey Secretary-Treasurer Feature Active members of the ISCA may vote on the slate at 4 - 5 Interlake Nationals 2019 at Indy the Annual Meeting, held on Friday, July 26 at 7 pm 5 Nationals links – registration and T-shirts at Indianapolis Sailing Club during Nationals. -

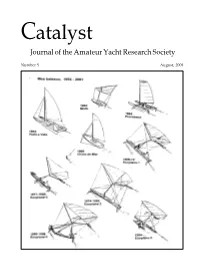

Catalyst N05 Jul 200

Catalyst Journal of the Amateur Yacht Research Society Number 5 August, 2001 Catalyst News and Views 3 Winds of Change 2001 6 Keiper Foils 7 Letters Features 10 Wind Profiles and Yacht Sails Mike Brettle 19 Remarks on Hydrofoil Sailboats Didier Costes 26 Designing Racing Dinghies Part 2 Jim Champ 29 Rotors Revisited Joe Norwood Notes from Toad Hill 33 A Laminar Flow Propulsion System Frank Bailey 36 Catalyst Calendar On the Cover Didier Costes boats (See page 19) AUGUST 2001 1 Catalyst Meginhufers and other antiquities I spent most of July in Norway, chasing the midnight sun Journal of the and in passing spending a fair amount of time in Norway’s Amateur Yacht Research Society maritime museums looking at the development history of the smaller Viking boats. Editorial Team — Now as most AYRS members will know, the Vikings rowed Simon Fishwick and sailed their boats and themselves over all of Northern Sheila Fishwick Europe, and as far away as Newfoundland to the west and Russia and Constantinople to the east. Viking boats were Dave Culp lapstrake built, held together with wooden pegs or rivets. Specialist Correspondents Originally just a skin with ribs, and thwarts at “gunwale” level, th Aerodynamics—Tom Speer by the 9 century AD they had gained a “second layer” of ribs Electronics—David Jolly and upper planking, and the original thwarts served as beams Human & Solar Power—Theo Schmidt under the decks. Which brings us to the meginhufer. Hydrofoils—George Chapman I’m told this term literally means “the strong plank”, and is Instrumentation—Joddy Chapman applied to what was once the top strake of the “lower boat”. -

NS14 ASSOCIATION NATIONAL BOAT REGISTER Sail No. Hull

NS14 ASSOCIATION NATIONAL BOAT REGISTER Boat Current Previous Previous Previous Previous Previous Original Sail No. Hull Type Name Owner Club State Status MG Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Club Name Owner Allocated Measured Sails 2070 Midnight Midnight Hour Monty Lang NSC NSW Raced Midnight Hour Bernard Parker CSC Midnight Hour Bernard Parker 4/03/2019 1/03/2019 Barracouta 2069 Midnight Under The Influence Bernard Parker CSC NSW Raced 434 Under The Influence Bernard Parker 4/03/2019 10/01/2019 Short 2068 Midnight Smashed Bernard Parker CSC NSW Raced 436 Smashed Bernard Parker 4/03/2019 10/01/2019 Short 2067 Tiger Barra Neil Tasker CSC NSW Raced 444 Barra Neil Tasker 13/12/2018 24/10/2018 Barracouta 2066 Tequila 99 Dire Straits David Bedding GSC NSW Raced 338 Dire Straits (ex Xanadu) David Bedding 28/07/2018 Barracouta 2065 Moondance Cat In The Hat Frans Bienfeldt CHYC NSW Raced 435 Cat In The Hat Frans Bienfeldt 27/02/2018 27/02/2018 Mid Coast 2064 Tiger Nth Degree Peter Rivers GSC NSW Raced 416 Nth Degree Peter Rivers 13/12/2017 2/11/2013 Herrick/Mid Coast 2063 Tiger Lambordinghy Mark Bieder PHOSC NSW Raced Lambordinghy Mark Bieder 6/06/2017 16/08/2017 Barracouta 2062 Tiger Risky Too NSW Raced Ross Hansen GSC NSW Ask Siri Ian Ritchie BYRA Ask Siri Ian Ritchie 31/12/2016 Barracouta 2061 Tiger Viva La Vida Darren Eggins MPYC TAS Raced Rosie Richard Reatti BYRA Richard Reatti 13/12/2016 Truflo 2060 Tiger Skinny Love Alexis Poole BSYC SA Raced Skinny Love Alexis Poole 15/11/2016 20/11/2016 Barracouta -

6 3 3 3 71.22 9 71.33 71.35 3 71.46 71.48 9 3 71.53 1 71.57 71.59 3

▪ Year Items Donor 71.1 6 Norton, Edward, Mrs. 71.2 4 Parise, Ralph, Mrs. 71.3 7 Norton, Edward, Mrs. 71.4 1 Dutton, Royal, Mrs. 71.5 1 Stevens, Hazel, Miss 71.6 3 Latham, David, Yrs. Z' 71.7 1 Greig, Wallace, Mrs. 71.8 1 Barton, Charles, Mrs. U) X D w 71.9 4 Reed, Everett, Mrs. < fr > Norton, Edward, Mrs. xc2E 71.10 19 0rt , D 71.11 1 Farnum, Harold, Mrs. .. >w hi 71.12 3 Central Congregational Church O D Emerson, Bradford, 0. p0 71.13 3 ,c Pettee, Cristy, Mrs. .< Da. 71.14 12 71.15 1 Skelton, Donald, Jr. 71.16 132 Scoboria, Marjorie, Miss 71.17 11 Stevens, Hazel, Miss 71.18 21 Stevens, Hazel, Miss 71.19 1 Mitchell, Ruth, Mrs. 71.20 1 Harrington School Children 71.21 1 Hiscoe, deMerritt, Dr. 71.22 3 Chew, Ernest, Mrs. 71.23 69 Turner, Gardner, Mrs. 71.24 1 Johnson, Ralph, Mr. & Mrs. 71.25 2 Lahue, Warren, C. 71.26 4 Stewart, Jessie,Atwood 71.27 1 Stewart, Frederick, Mrs. 71.28 32 Stevens, Hazel, Miss ..-- 71.29 13 Warren, Miriam, Miss 71.30 11 Davis, Carl, J. 71.31 9 Brown, Berniece, Miss, Estate 71.32 8 Wolf, Roacoe, Mrs. 71.33 1 Marchand, George, Mr. & Mrs. 71.34 15 Wells, Evelyn, Miss 71.35 1 Gumb, Lena, Miss 71.36 28 Eddy, Donald, Mrs. 71.37 8 Norton, Edward, Mrs. 71.38 11 Scoboria, Marjorie, Miss 71.39 3 Ball, Lester, W. 71.40 1 deJager, Melvin, Yrs. -

UK Cherub Class Rules 2011

UK Cherub Class Rules 2011 1 INTRODUCTION The object of these rules is to provide a set of rules to which inexpensive high performance dinghies may be designed and built. 2 CONSTITUTION 2.1 ADMINISTRATION The Association shall hold an Annual General Meeting (AGM), normally at the National Championship. The date and venue of the AGM shall be published at least one month before it is due to be held. The AGM shall elect the following Association Officials: President, Secretary, Treasurer, Registrar, and Technical Officer. It may also elect the following additional Officials: Magazine Editor, Publicity Officer, Fixtures Secretary. All these Officials shall be members of the Association Committee. The AGM may elect additional committee members up to a total of ten. 2.2 AMENDMENTS TO CLASS RULES Changes to these Class Rules may only be made as a result of a 2/3 majority vote in favour in a postal ballot of all paid up members of the association. Proposals for changes to these rules may be submitted to the Association Committee at any time. Such proposals must be signed by five members and must detail the precise wording of the proposed change. The Committee shall consider each proposal and may suggest possible changes to the proposers. The final wording shall be agreed upon within four months of the original submission. The Committee shall, within a further three months, conduct a postal ballot of all members. The ballot shall include the full detailed wording of the proposals, any explanation submitted by the proposers and any comments from the Committee or Technical Officer. -

Burnsco 2021 Sunburst National Championships

Burnsco 2021 Sunburst National Championships Thursday 7th – Monday 11th January 2021 Notice of Race The Organising Authority is the Pleasant Point Yacht Club South Brighton Park | Beatty Street | Christchurch 8641 Note: The notation ‘[DP]’ in a rule in the Notice of Race means that the penalty for a breach of that rule may, at the discretion of the protest committee, be less than disqualification. 1. Rules 1.1. The will event will be governed by the ‘rules’ as defined in the Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS). 1.2. The Yachting New Zealand Safety Regulations Part 1 shall apply. 1.3. The Sailing Instructions will consist of the instructions in RRS Appendix S, Standard Sailing Instructions, and Supplementary Sailing Instructions that will be on the official notice board located in the Race Office. 1.4. Appendix T, Arbitration, will apply. 2. Advertising 2.1 Boats may be required to display advertising chosen and supplied by the Organising Authority. 3. Eligibility and Entry 3.1. The event is open to all boats of the Sunburst class. 3.2. Eligible skippers may enter by completing the attached form and either (a) sending it, together with the required fee to: Burnsco 2021 Sunburst National Championships NOR Approved 1 The Organising Committee Burnsco 2021 Sunburst Nationals 79 Ascot Avenue North New Brighton Christchurch 8083 or (b) Online (preferred): Entries to: [email protected] Payment: Bank account number: 03-0814-0208054-00 Particulars: Sunburst; Reference: Surname By Monday 7 December 2020. 3.3. Late entries. A late entry may be accepted at the Organising Authority’s discretion until Thursday 31 December 2020. -

Northbridge Sailing Club 2015-2016 Season Report Part 2

Main Clubhouse: Bethwaite Lane, Clive Park, Northbridge Seaforth Clubhouse annex: Sangrado Street, Seaforth Postal Address: PO Box 39 Northbridge NSW 2063 Northbridge Sailing Club 2015-2016 Season Report Part 2 Flying 11 Report 2015-2016 The 2015/16 season has seen the Flying 11 Program go from strength to strength with a record 17 boats registered and regular fleets in excess of 12. The kids have had FUN and it is always a tremendous sight to see them learn and grow in confidence. We had a range of abilities from front of the fleet regatta sailors through to club sailors still learning to confidently sail in all weathers and everything in between. The Flying 11 Program has been ably coached by Evan Andrews and assisted by a hard- working and enthusiastic parent group. Club Championship The Club Championship was a close tussle between Rebecca Hancock/Eve Peel and Jack Taylor/Shuhei Tomishima with Rebecca and Eve proving the form sailors of the season. The club Championship places were 1st Rebecca Hancock and Eve Peel, 2nd Jack Taylor and Shuhei Tomishima and 3rd Kashi Saunders and Bezi Saunders. Northridge Sailing Club Season Report 2015-16 page 2 Figure 1 Flying 11 Sailing at its Best – Fresh and Fast Other NSC Trophies In other NSC trophies Jack Taylor and Shuei cleaned up the Afternoon Point Score, followed by Kashi and Bezi and Maddy Sloane and Isobel Gosper. Maddy and Isobel turned out to be the perpetual trophy specialists winning the President’s Plate, the Punchbowl Pennant and the Commodores Cup with Warwick Taylor and Namika Keogh 2nd and Sasha Zenari and Thomas Westwood 3rd in the President’s Plate. -

Tell Tales October 2016

PLEASEFREE TAKE ONE October 2016 IN THIS ISSUE ‘Spot the Yot’ and win a prize Racing Results ‘YOUTH SAILING FEATURE‘ Scallops Working Bee. Youth Sailing Update Learn to sail - getti ng started Calendar Sponsor Special - Sailwork Learn to Sail - Pathways October’s Events Calendar Community Noti ces 2 | Tell Tales IN THIS ISSUE... If you have anything you’d like to see published in here, Community Notices Commodore’s Report..........................3 or letters, articles, stories etc. please Youth Sailing Update...........................4 email [email protected] ‘Spot the Yot’ and win a prize..............5 Racing News.......................................6 Membership News..............................6 Scallops...............................................6 Lets get Social.....................................7 Twilight Racing...................................8 Working Bee.......................................9 Learn to sail - getti ng started..............10 Calendar Sponsor Special..................12 Craig Gurnell Learn to Sail - Pathways....................13 DIRECTOR Community Noti ces...........................15 [email protected] Loft: Norfolk Place October Calendar..............................16 skype: willissails PO Box 453, Kerikeri On the cover: Young Sailors having fun 09 407 8153 Photo Credit - Robbs Hielkema 021 786 080 www.willissails.co.nz Advertise in Tell Tales ...and be seen by hundreds of people in Opua and Paihia every month. Rob 1 year - $300 ($25 per advert) Galley 6 months - $150 Northland Spars & Rigging 3 months - $100 We provide expert services to local 1 month - $50 and overseas yachts. You can rely on +64 (0)9 402 6280 our expertise and products. Our +64 (0)273 322 381 Call Sheila on 09 402 6924 complete range of facilities allow us 2 Ban Street, Opua, NZ to service all of your spar and [email protected] or email [email protected] rigging needs.