Meursaults When Meursault, the Hero of Albert Camus's the Stranger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fonds Documentaire Bibliothèque St-Maixant Avril 2021

Fonds documentaire bibliothèque St-Maixant Avril 2021 Les données sont triées par catégorie et par prénom d'auteur. Vous pouvez faire une recherche en tapant ctrl+F. TITRE AUTEUR EDITEUR CATEGORIE Le roi du château Adrien Albert et Jeanne Taboni Misérazzi L'école des loisirs Album Une princesse à l'école Agnès de Lestrade Editions lito Album Le cimetière des mots doux Agnès Ledig et Frédéric Pillot Albin Michel jeunesse Album Le petit arbre qui voulait devenir un nuage Agnès Ledig et Frédéric Pillot Albin Michel jeunesse Album Les Dragon des pluies Alain Korkos et Katharina Buchoff Bayard jeunesse Album La souris qui sauva toute une montagne Alain Serres et Aurélia Fronty Rue du monde Album Têtes de bulles Alain Serres et Martin Jarrie Rue du monde Album Un petit air de famille Alain Serres et Martin Jarrie Rue du monde Album Brosse et Savon Alan Mets L'école des loisirs Album Mes lunettes de rêve Alan Mets L'école des loisirs Album John Cerise Alan Wets L'école des loisirs Album Maman-dlo Alex Godard Albin Michel jeunesse Album Même pas peur, Vaillant Petit Tailleur ! Alexandre Jardin et Harvé Le Goff Hachette jeunesse Album Nina Alice Brière-Haquet et Bruno Liance Gallimard jeunesse Album La boîte à outils de Sidonie Aline de Pétigny Editions Pour penser Album La princesse et la bergère et deux autres contes Aline de Pétigny Editions Pour penser Album Kerity La maison des contes Anik Le Ray Flammarion Album Histoires de dragons et autres monstres Anita Ganeri et Alan Baker Gründ Album La couleur des émotions Annallenas Editions quatre -

6-Jeudis-De- Lodeon.Pdf

L’ODÉON VOUS PROPOSE DES SOIRÉES CLÉ EN MAIN Accueil personnalisé pour vos invités dans le hall du théâtre Places réservées et groupées en première catégorie Espace de réception partiellement ou entièrement privatisé Remise des programmes de spectacle à l’arrivée de vos invités Service de vestiaire Orientation et filtrage des invités au moment de la réception par l’équipe d’accueil Prise en charge de l’organisation et de la logistique de votre réception Terrasse du Théâtre de l’Odéon 6e © Benjamin Chelly NOS FORMULES Formule champagne Une coupe de champagne, avant, à l’entracte ou après la représentation 90 euros TTC / personne dans un espace partiellement privatisé 120 euros TTC / personne dans un espace entièrement privatisé Formule cocktail Cocktail 12 pièces et coupe de champagne avant ou après la représentation 190 euros TTC / personne dans un espace partiellement privatisé 250 euros TTC / personne dans un espace entièrement privatisé Richard III de William Shakespeare, mis en scène par Thomas Ostermeier © Arno Declair L’ODÉON-THÉÂTRE DE L’EUROPE DEUX SALLES POUR RECEVOIR VOS INVITÉS Le Théâtre de l’Odéon / 6e Inauguré en 1782 par Marie-Antoinette, le Théâtre de l’Odéon est le plus ancien théâtre-monument de Paris. LE GRAND FOYER Situé au cœur du théâtre, ce lieu est idéal pour partager une coupe de champagne avec vos invités dans un espace partiellement privatisé. De 10 à 20 personnes LES STUDIOS GÉMIER, SERREAU ET LA TERRASSE Espaces de répétition pour les artistes, les deux studios sont situés au troisième niveau du théâtre. Séparés l’un de l’autre par une vue plongeante sur le grand foyer, ils donnent accès à la terrasse du théâtre, offrant une vue imprenable sur la place de l’Odéon. -

Here Was Obviously No Way to Imagine the Event Taking Place Anywhere Else

New theatre, new dates, new profile, new partners: WELCOME TO THE 23rd AND REVAMPED VERSION OF COLCOA! COLCOA’s first edition took place in April 1997, eight Finally, the high profile and exclusive 23rd program, years after the DGA theaters were inaugurated. For 22 including North American and U.S Premieres of films years we have had the privilege to premiere French from the recent Cannes and Venice Film Festivals, is films in the most prestigious theater complex in proof that COLCOA has become a major event for Hollywood. professionals in France and in Hollywood. When the Directors Guild of America (co-creator This year, our schedule has been improved in order to of COLCOA with the MPA, La Sacem and the WGA see more films during the day and have more choices West) decided to upgrade both sound and projection between different films offered in our three theatres. As systems in their main theater last year, the FACF board an example, evening screenings in the Renoir theater made the logical decision to postpone the event from will start earlier and give you the opportunity to attend April to September. The DGA building has become part screenings in other theatres after 10:00 p.m. of the festival’s DNA and there was obviously no way to imagine the event taking place anywhere else. All our popular series are back (Film Noir Series, French NeWave 2.0, After 10, World Cinema, documentaries Today, your patience is fully rewarded. First, you will and classics, Focus on a filmmaker and on a composer, rediscover your favorite festival in a very unique and TV series) as well as our educational program, exclusive way: You will be the very first audience to supported by ELMA and offered to 3,000 high school enjoy the most optimal theatrical viewing experience in students. -

Bibete2018.Pdf

Prenez le large et voyagez au fil des pages... Méditerranée : 100 titres proposés par les lecteurs(trices). Véritable plongée dans la littérature des pays du pourtour de la Méditerranée où chacun d’entre vous puisera ses titres à lire et à glisser dans sa valise, son sac de plage, de montagne, de randonnée… La part belle est faite aux romans mais vous y trouverez des films et de la musique, en majorité d’auteurs(res) contemporains(nes) Ce large choix existe grâce aux lectrices et lecteurs. Merci à toutes et à tous, pour leur participation. Algérie France Maroc Crète Grèce Palestine Croatie Israël Syrie Egypte Italie Tunisie Espagne Liban Turquie Cap sur la mediterranee CD MAGAZINE MEDITERRANEO de Christina Pluhar MÉDITERRANÉE : 30 Un an après le succès ÉCRIVAINS POUR de Los Pájaros perdidos, VOYAGER LIVRE Christina Pluhar, vous invite Le magazine littéraire EN CHEMINANT à traverser la Méditerranée N° 580 – Juin 2017 en musique. On se laisse Un dossier sur la Grande AVEC HÉRODOTE griser par les voix de bleue à travers le regard Textes traduits et Mísia, Nuria Rial, Vincenzo de grands auteurs français commentés par Jacques Capezzuto, Raquel et étrangers. Lacarrière Andueza ou Katerina Voyageur infatigable, Papadopoulou. Jacques Lacarrière a choisi RECOMMANDÉ PAR LES cette fois de mettre ses pas BIBLIOTHÉCAIRES dans ceux d’un voyageur RECOMMANDÉ PAR célèbre du Ve siècle av. CATHERINE GATINEAUD LIVRE J.-C., l’historien grec Hérodote, dont il présente VOIX VIVES DE ici les fameuses Histoires en TÉMOIGNAGES MÉDITERRANÉE Perse et dans les pays du LE PAYS NATAL EN MÉDITERRANÉE Proche-Orient. -

DOSSIER DE PRESSE - 15 Juin 2017

DOSSIER DE PRESSE - 15 juin 2017 - Le Livre sur la Place est organisé par la Ville de Nancy en lien avec l'association de libraires "Lire à Nancy" ___ 2 Sommaire Le Livre sur la Place, c’est avant tout… 4 Jean-Christophe Rufin de l'Académie française, président 2017 6 Les 10 Académiciens Goncourt, présents à Nancy 8 Au cœur de l’espace XVIIIème, patrimoine mondial de l’Humanité 10 Les émissions phares de France Inter 12 Ils font la rentrée littéraire et sont à Nancy 13 Près de 100 débats et entretiens 14 Place à la BD ! 16 Trois grandes lectures - spectacles 18 Programmation internationale 20 Les Grandes Rencontres du Livre sur la Place 23 Les 6 prix décernés pendant le salon 24 "La Nouvelle de la classe" 32 Plus de 5 000 jeunes vivent le livre sur la Place 33 A la rencontre de nouveaux lecteurs 34 Autour du livre 36 Des écrivains partout ! 37 Contacts 38 Principaux partenaires 39 3 LE LIVRE SUR LA PLACE, C'EST AVANT TOUT… Près de 40 ans de fidélité des Académiciens Goncourt. Depuis sa création en 1979, ils parrainent le Livre sur la Place auquel ils sont particulièrement attachés et ont toujours à cœur le rendez-vous de Nancy qu’ils disent "incontournable" ! L’enthousiasme des écrivains à vouloir converger vers Nancy où, outre les dédicaces, ils nouent un dialogue particulièrement fécond avec leurs lecteurs. Tous se retrouveront sous le chapiteau de l’actualité littéraire. Près de 200 d'entre eux seront en débats ou entretiens. Beaucoup d’éditeurs aiment aussi être à Nancy pour cette fête du Livre, chaleureuse et animée. -

Les Fils Meurent Avant Les Pères / Ceux Qui M'aiment Prendront Le

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 10:34 24 images Les fils meurent avant les pères Ceux qui m’aiment prendront le train de Patrice Chéreau Stéphane Lépine Cinéma et engagement – 2 Numéro 93-94, automne 1998 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/24176ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (imprimé) 1923-5097 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Lépine, S. (1998). Compte rendu de [Les fils meurent avant les pères / Ceux qui m’aiment prendront le train de Patrice Chéreau]. 24 images, (93-94), 78–79. Tous droits réservés © 24 images, 1998 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ HOMME DE THÉÂTRE, HOMME DE CINÉMA Ceux qni m'aiment de vue artistique. En fait, tout cela est le produit de ce que je suis. J'ai connu beaucoup de gens, j'ai ri avec beaucoup de gens, effecti de Patrice Chéreau vement j'ai vu mourir des gens, j'ai assisté à des entetrements, j'ai remarqué ce qui se passait après un enterrement, comment les gens reprenaient leur vie, comment la gaieté, la vitalité, l'envie de vivre reprenaient le dessus. -

The Daoud Affair

Uppsala Rhetorical Studies Studia Rhetorica Upsaliensis CAN A PERSON BE ILLEGAL? ––––– Refugees, Migrants and Citizenship in Europe Jean Lassègue The Daoud Affair ––––– Alexander Stagnell, Louise Schou Therkildsen, Mats Rosengren (eds) Jean Lassègue – The Daoud Affair – Introduction Te aim of this text is to refect on the relationship between two Politics, Literature, and Migration of genres of discourse when they are alternatively used by the same Ideas in a Time of Crisis writer in a time of intense political, social, and identity upheaval, as Europe is experiencing it through the migrant crisis. Te two genres that will be studied are the political genre in a broad sense (press articles belong to this category) where a writer takes the foor in his or her name, and the literary genre, conceived as a form of imaginary and social endeavor where the writer is not supposed to be identifed with his or her fctional characters. It is well known that the distinction between the political and the literary can become fuzzy in a time of crisis: the cases of Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Ezra Pound, whose fctional productions cannot be separated from their political commitments to fascism, spring immediately to mind. But the embarrassment such cases generate should not indulge us in a comfortable self-censorship and prevent us from recognizing a very specifc political function of literature. It is this very function that will be investigated here in relation to a contemporary case: Te Algerian writer Kamel Daoud who unwillingly became involved in what was eventually called the ‘Daoud Afair’ – an expression coined by Adam Shatz, an American literary critic and personal friend of Daoud, in an article published by Te London Review of Books in March 2016.1 1. -

Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier Olivier Assayas

MK2 presents Juliette Charles Jérémie BINOCHE BERLING RENIER A film by Olivier ASSAYAS photo : Jeannick Gravelines MK2 presents I wanted, as simply as possibly, to tell the story of a life-cycle that resembles that of the seasons… Olivier Assayas a film by Olivier Assayas Starring Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier France, 35mm, color, 2008. Running time : 102’ in coproduction with France 3 Cinéma and the participation of the Musée d’Orsay and of Canal+ and TPS Star with the support of the Region of Ile-de-France in partnership with the CNC I nt E rnationa L S A LE S MK2 55 rue Traversière - 75012 Paris tel : + 33 1 44 67 30 55 / fax : + 33 1 43 07 29 63 [email protected] PRESS MK2 - 55 rue Traversière - 75012 Paris tel : + 33 1 44 67 30 11 / fax : + 33 1 43 07 29 63 SYNOPSIS The divergent paths of three forty something siblings collide when their mother, heiress to her uncle’s exceptional 19th century art collection, dies suddenly. Left to come to terms with themselves and their differences, Adrienne (Juliette Binoche) a successful New York designer, Frédéric (Charles Berling) an economist and university professor in Paris, and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier) a dynamic businessman in China, confront the end of childhood, their shared memories, background and unique vision of the future. 1 ABOUT SUMMER HOURS: INTERVIEW WITH OLIVIER ASSAYAS The script of your film was inspired by an initiative from the Musée d’Orsay. Was this a constraint during the writing process? Not at all. In the beginning, there was the desire of the Musée d’Orsay to associate cinema with the celebrations of its twentieth birthday by offering «carte blanche» to four directors from very different backgrounds. -

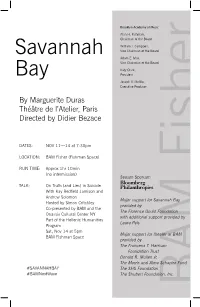

Savannah TALK: (No Intermission) Program

Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Savannah Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, Bay President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer By Marguerite Duras Théâtre de l’Atelier, Paris Directed by Didier Bezace DATES: NOV 11—14 at 7:30pm LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 10min (no intermission) Season Sponsor: TALK: On Truth (and Lies) in Suicide With Kay Redfield Jamison and Andrew Solomon Major support for Savannah Bay Hosted by Simon Critchley provided by Co-presented by BAM and the The Florence Gould Foundation Onassis Cultural Center NY with additional support provided by Part of the Hellenic Humanities Laura Pels Program Sat, Nov 14 at 5pm Major support for theater at BAM BAM Fishman Space provided by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Donald R. Mullen Jr. The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund #SAVANNAHBAY The SHS Foundation #BAMNextWave The Shubert Foundation, Inc. BAM Fisher Savannah Bay ABOUT Savannah Bay NY Premiere DIRECTOR’S NOTE Two women in a pristine white room: The overarching subject of Savannah In French with English titles one young, one old. “Who was she?” Bay is the union of two women and one asks the other, referring to a third the role play in which they engage— DIRECTOR who had long ago met a boy, fallen in perhaps daily—to recognize one Didier Bezace love, and bore his child before drown- another. Stemming from a hidden and ing herself. buried traumatic event, which they ARTISTIC MANAGEMENT bring to the surface from a shred of Dyssia Loubatière Unfolding in the melancholic half- memory, they attempt to win each light of memory, Savannah Bay is a other over, to recognize and to love PERFORMERS mesmerizing two-character drama one another. -

Joël Pommerat Et Catherine Frot Triomphent Aux Molières La Grande Nuit Du Théâtre S’Est Tenue Le 23 Mai Aux Folies Bergère

0123 MERCREDI 25 MAI 2016 culture | 17 Joël Pommerat et Catherine Frot triomphent aux Molières La grande nuit du théâtre s’est tenue le 23 mai aux Folies Bergère THÉÂTRE n a ri aux Molières. Succédant à Nicolas Bedos, le comédien et humoriste Alex Lutz a Oparfaitement rempli son rôle de maître de cérémonie de cette 28e Nuit des récompenses du théâtre privé et public enregistrée, lundi 23 mai, aux FoliesBergère à Paris et retransmise sur France 2. Usant de son don pour le travestisse ment et le grimage, Alex Lutz a joué avec talent à l’ouvreuse débu tante, au vieux comédien un peu grivois et au cheval de cirque. Côté palmarès, le grand vain queur de cette nuit des Molières était absent : Joël Pommerat (en Catherine tournée en Chine) a reçu quatre Frot, statuettes. Pour sa fresque sur la Molière de Révolution française, Ça ira (1) Fin la meilleure de Louis – qui a fait un triomphe comédienne au théâtre NanterreAmandiers – d’un il a obtenu le Molière du théâtre spectacle public, du metteur en scène et de privé pour l’auteur francophone de l’année. « Fleur de Mais aussi le Molière du jeune pu cactus ». blic pour Pinocchio présenté au PATRICK KOVARIK/AFP théâtre de l’Odéon. La deuxième gagnante de cette soirée est Ca therine Frot qui, en remportant le Molière de la comédienne dans un spectacle de théâtre privé pour Fleur de Cactus mise en scène par Michel Fau, réalise un doublé 2016 inédit après son César de la meilleure actrice pour Margue rite, de Xavier Giannoli. -

A Film by Olivier Assayas

DEMONLOVER A film by Olivier Assayas Distributor Contact: New Yorker Films 220 East 23rd St., Ste. 409 New York, NY 10010 Tel: (212) 645-4600 Fax: (212) 683-6805 [email protected] DEMONLOVER CREDITS Directed by OLIVIER ASSAYAS Written by OLIVIER ASSAYAS Producer EDOUARD WEIL XAVIER GIANNOLI Dir. Of Photography DENIS LENOIR Editor LUC BARNIER Sound PHILIPPE RICHARD Music SONIC YOUTH CAST Diane CONNIE NIELSEN Herve CHARLES BERLING Elise CHLOE SEVIGNY Elaine GINA GERSHON Volf JEAN-BAPTISTE MALARTRE Karen DOMINIQUE REYMOND Friend of Diane JULIE BROCHEN www.NewYorkerFilms.com France, 2002 117 min, Color In French and Japanese with English Subtitles 2.35, Dolby Digital 2 SYNOPSIS Demonlover is Olivier Assayas’ breathtaking vision of our spectacle-driven modern global society. On the surface, the film follows Diane (Connie Nielsen) who works for VolfGroup, a hugely powerful conglomerate that is negotiating the acquisition of TokyoAnime, whose revolutionary pornographic 3-D manga is set to annihilate the competition in an extraordinarily lucrative market. Two companies are battling for exclusive rights to Volf’s new images on the Web: magnatronics and Demonlover. MAgnatronics has recruited Diane to torpedo Demonlover from within and she finds a connection with the latter company and an interactive torture Web site known as “The Hellfire Club.” However, Diane is soon challenged every step of the way by her amoral colleague (Charles Berling), and antagonistic and mysterious assistant (Chloe Sevigny) and an outspoken, pot-smoking American executive (Gina Gershon). Brilliantly shot by Denis Lenoir (who previously collaborated with Assayas on films such as Late August, Early September and Cold Water), the film captures a culture spiraling out of control in which reality is posited as a video game and where every twist escalates the film to a new level. -

Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier Olivier Assayas

Palace Films presents Juliette Charles Jérémie BINOCHE BERLING RENIER A film by Olivier ASSAYAS photo : Jeannick Gravelines Official Selection 2008 New York Film Festival 2008 Toronto Film Festival Prix Louis Delluc 2008 Nominee Piers Handling, Toronto Film Festival «Olivier Assayas’s new film is not a radical departure from his previous work, but the differences are nonetheless striking. It has a mature look and feel, made by an artist completely at ease with the medium. Without striving for effect, Assayas is happy to let the material speak for itself. And what a magnificent achievement it is. Summer Hours deals with ideas of tradition and family heritage, using a house and a garden as a metaphor for cultural memory. Incisively written, superbly acted by some of France’s finest performers and boasting a delicately understated approach to the subject matter, Assayas’s new film moves effortlessly through its narrative with all the grace of Renoir at the height » of his powers. I wanted, as simply as possibly, to tell the story of a life-cycle that resembles that of the seasons… Olivier Assayas presents a film by Olivier Assayas Starring Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier France, 35mm, color, 2008. Running time : 102’ Australian Release 2 April, 2009 Website www.summerhours.com.au PRESS Paige Diamond National Publicity & Promotions Manager [email protected] T: +61 2 9357 5755 F: +61 2 9331 7145 M: +61 431 106 082 For images please visit www.palacefilms.com.au/gallery Username: PFGallery Password: pfguest SYNOPSIS The divergent paths of three forty something siblings collide when their mother, heiress to her uncle’s exceptional 19th century art collection, dies suddenly.