Pruning Apple and Pear Trees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

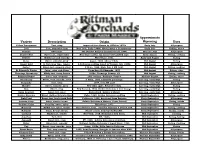

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Treeid Variety Run 2 DNA Milb005 American Summer Pearmain

TreeID Variety Run 2 DNA Run 1 DNA DNA Sa… Sourc… Field Notes milb005 American Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2g016 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2f017 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2f018 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain eckh001 BaldwinDot" Baldwin-SSE6 eckh008 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt007 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt011 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 schd019 Ben Davis Ben Davis mild006 Ben Davis Ben Davis wayb004 Ben Davis Ben Davis andt019 Ben Davis Ben Davis ostt014 Ben Davis Ben Davis watt008 Ben Davis Ben Davis wida036 Ben Davis Ben Davis eckg002 Ben Davis Ben Davis frea009 Ben Davis Ben Davis frei009 Ben Davis Ben Davis frem009 Ben Davis Ben Davis fres009 Ben Davis Ben Davis wedg004 Ben Davis Ben Davis frai006 Ben Davis Ben Davis frag004 Ben Davis Ben Davis frai004 Ben Davis Ben Davis fram006 Ben Davis Ben Davis spor004 Ben Davis Ben Davis coue002 Ben Davis Ben Davis couf001 Ben Davis Ben Davis coug008 Ben Davis Ben Davis, error on DNA sample list, listed as we2a023 Ben Davis Bencoug006 Davis cria001 Ben Davis Ben Davis cria008 Ben Davis Ben Davis we2v002 Ben Davis Ben Davis we2z007 Ben Davis Ben Davis rilcolo Ben Davis Ben Davis koct004 Ben Davis Ben Davis koct005 Ben Davis Ben Davis mush002 Ben Davis Ben Davis sc3b005-gan Ben Davis Ben Davis sche019 Ben Davis, poss Black Ben Ben Davis sche020 Ben Davis, poss Gano Ben Davis schi020 Ben Davis, poss Gano Ben Davis ca2e001 Bietigheimer Bietigheimer/Sweet -

Progress in Apple Improvement

PROGRESS IN APPLE IMPROVEMENT J. R. MAGNESS, Principal Pomologisi, 13ivision of Fruit and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, liureau of Plant Industry ^ A HE apple we liave today is J^u" rciuovod from tlic "gift of the gods'' wliich prehistoric man found in roaming the woods of western Asia and temperate Europe. We can judge that apple only by the wild apples that grow today in the area between tlie Caspian Sea and Europe, which is believed to be the original habitat of the apple. These apples are generally onl>r 1 to 2 inches in diameter, are acici and astringent, and are far inferior io the choice modern horticultural varieties. The improvement of the apple through tlie selection of the best types of the wild seedlings goes far baclv to the very beginning of history. Methods of budding and grafting fiiiits were Icnown more than 2,000 years ago. According to linger, C^ato (third century, B. C.) knew seven different apple varieties, l^liny (first centiuy, A. D.) knew^ 36 different kinds. By tlie time the iirst settlers froni Europe were coming to the sliores of North America., himdreds of apple varieties had been named in European <M)unt]*ies, The superior varieties grown in l^^urope in the seventeenth century had, so far as is known, all developed as chance seedlings, but garden- ers had selected the best of the s(>edling trees îvnd propagated them vegetatively. The early American settlers, ptirticiilarly those from the temperate portions of Europe, who came to the eastern coast of North Amer- ica, brought with them seeds and in some cases grafted trees of European varieties. -

The 18Thc Nouvelle France Kitchen

The 18thC Nouvelle France Kitchen Garden, Pantry, Tools & Recipes Gardens - Potagers In Louisiane we find ordered landscapes surrounded by palisades with vegetable beds in geometric patterns, trellises (grapes and espaliers) and orchards in the rear—simple yet adequate organization of space that would sustain early settlers. Orchards – Summer Apples Summer Rambo Hightop Sweet Sweet Bough Astrachan Gravenstein Maiden Blush Williams Summer Rose Woolman’s Early Maiden Blush Or chards – Fall Apples Fameuse Baldwin Calville Rouge Tompkins King d’Automne Yellow Bellflower Dyer Westfield Carpentin Seek-No-Further Esopus Spitzenburg Golden Pearmain Old Nonpareil Hunt Russet Reine des Reinettes Starkey Roxbury Russet Ross Nonpareil Ribston Court of Wick Black Gilliflower Scarlet Crofton Newton Calville Rouge d’Automne Orchards – Winter Apples White Winter Permain Calville Blanc d’Hivre Court-Pendu Plat Lady Calville Blanc d’Hivre Orchards - Pears Winter Nelis Seckel Harovin Sundown French Butter Forelle Flemish Beauty Dorondeau Corsica Bosc Bartlett Anjou French Butter Other- Fruits, Berries, Nuts Berries, wild and cultivated Cranberries Strawberries Blueberries Currants Gooseberries Walnuts, fresh or pickled Hazelnuts Almonds Lemons Vegetables Carrots Several Species of Cucumbers Pumpkins Few Artichokes Several Kinds of Beans Horseradish Several Kinds of Peas Leeks (Yellow and Green) Lettuces Turkish Beans Melons Turnips in Abundance Parsnips Sparingly Watermelons [White Pulp Radishes (Most Common) and Red Pulp] Red Onions White Cabbage Red Beets -

The Decline of the Apple

The Decline of the Apple The development of the apple in this century has been partial- ly a retrogression. Its breeding program has been geared almost completely to the commercial interests. The criteria for selection of new varieties have been an apple that will keep well under refrigeration, an apple that will ship without bruising, an apple of a luscious color that will attract the housewife to buy it from the supermarket bins. That the taste of this selected apple is in- ferior has been ignored. As a result, sharpness of flavor and variety of flavor are disappearing. The apple is becoming as standardized to mediocrity as the average manufactured prod- uct. And as small farms with their own orchards dwindle and the average person is forced to eat only apples bought from commercial growers, the coming generations will scarcely know how a good apple tastes. This is not to say that all of the old varieties were good. Many of them were as inferior as a Rome Beauty or a Stark’s Delicious. But the best ones were of an excellence that has almost dis- appeared. As a standard of excellence by which to judge, I would set the Northern Spy as the best apple ever grown in the United States. To bite into the tender flesh of a well-ripened Spy and have its juice ooze around the teeth and its rich tart flavor fill the mouth and its aroma rise up into the nostrils is one of the outstanding experiences of all fruit eating. More than this, the Spy is just as good when cooked as when eaten raw. -

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community Elizabeth Shaver Illustrations by Elizabeth Lee PUBLISHED BY THE SHAKER HERITAGE SOCIETY 25 MEETING HOUSE ROAD ALBANY, N. Y. 12211 www.shakerheritage.org MARCH, 1986 UPDATED APRIL, 2020 A is For Apple 3 Preface to 2020 Edition Just south of the Albany International called Watervliet, in 1776. Having fled Airport, Heritage Lane bends as it turns from persecution for their religious beliefs from Ann Lee Pond and continues past an and practices, the small group in Albany old cemetery. Between the pond and the established the first of what would cemetery is an area of trees, and a glance eventually be a network of 22 communities reveals that they are distinct from those in the Northeast and Midwest United growing in a natural, haphazard fashion in States. The Believers, as they called the nearby Nature Preserve. Evenly spaced themselves, had broken away from the in rows that are still visible, these are apple Quakers in Manchester, England in the trees. They are the remains of an orchard 1750s. They had radical ideas for the time: planted well over 200 years ago. the equality of men and women and of all races, adherence to pacifism, a belief that Both the pond, which once served as a mill celibacy was the only way to achieve a pure pond, and this orchard were created and life and salvation, the confession of sins, a tended by the people who now rest in the devotion to work and collaboration as a adjacent cemetery, which dates from 1785. -

Tree Physical Characteristics 1 Variety Vigor 36-305 Adam's Pearmain

Tree Physical Characteristics 1-few cankers 2- moderate (less than 10 lesions), non lethal 3- girdling, lethal or g-50-90% 1 - less than 5% extensive a- f-35-50% 2 - 5-15% anthracnose canker p -less than 35% 3 - More than 15% 3-strongest 1 yes or no n- nectria (from vertical) 4 - severe (50% ) alive or dead 1-weakest branch dieback/cold 1 Variety leaf scab canker angle damage mortality notes vigor 36-305 y a 1 g 1 a perfect form 3 1 weak, 1 decent, spindly Adam's Pearmain n a 1 p 2 a growth 2 Adanac n 0 f 3 a weak 1 no crop in 11 Akero y f a years 2 Albion n 0 f 0 a 2 only 10% of fruit had scab, none on leaves, Alexander n 0 f a bullseye on fruit 3 bad canker, Alkmene y a 1,3 f 0 a bushy 2 vigorous but Almata y f 0 a lanky 3 red 3/4 fruits, nice open form, Almey y 0 g 1 a severe scab 3 Altaiski Sweet y a Alton y g 1 a 3 American Beauty y f 0 a slow to leaf out 3 Amsib Crab n f 1 a 2 looks decent, Amur Deburthecort y 2 a cold damage early leaf drop, Anaros y 2 g 0 a nicely branched 3 dieback spurs Anis n a 1 , other cankers p 1 a only 1 Anise Reinette y a 1 f 2 a 2 Anisim y a 1 p 1 a leader dieback 3 Ann's n 0 f 2 a local variety 2 Anoka y f a 2 Antonovka 81 n g a 3 Antonovka 102 n g a 3 Antonovka 109 n f a 3 antonovka 52 n g a 3 Antonovka 114 n g a 3 Antonovka 1.5 n a1 g 0 a 3 n f 0 a 3 Antonovka 172670-B Page 1 of 17 Tree Physical Characteristics Antonovka 37 n g a 3 Antonovka 48 n g a 3 Antonovka 49 n g a 3 Antonovka 54 n f a slow to leaf out 3 Antonovka Debnicka n f 0 a 3 Antonovka Kamenichka n a 1 f 0 a 3 Antonovka Michurin n 0 f -

Orchard Management Plan

Inventory, Condition Assessment, and Management Recommendations for use in preparing an Orchard Management Plan for the Fruita Rural Historic District, Capitol Reef National Park By Kanin Routson and Gary Paul Nabhan, NAU Center for Sustainable Environments, 2007 In fulfillment of CP-CESU Contract H1200040002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Acknowledgements Historical Overview Relationship to national/ regional history Varieties previously known but lost Fruit production practices lost Contributing and non-contributing orchards/Extant historic character Existing Conditions Condition assessment of the orchards Demographic summary of the trees of Fruita Inventory, History, Condition Assessment, and Recommendations for Each Orchard in the Fruita Historic District Condition Assessment of the orchards Species composition of the orchards Site-specific history/ Character of orchards in period of significance Orchard-specific management recommendations: Preservation: Retain current (historic) appearance through cyclic maintenance and replacement-in-kind Restoration: Return appearance back to historic condition by removing later additions, and replacing missing features Rehabilitation: Preserve historic characteristics and features; make compatible alterations and additions to orchard Reconstruction: Re-plant a vanished orchard using excellent evidence Calendar for Maintenance Monitoring Time and frequency of activities General maintenance Procedures Pruning, irrigation, planting, and scion-wood collecting Long-Term Management Objectives Conclusions References Appendix Registry of Heirloom Varieties at Capitol Reef/Southwest Regis-Tree 1 Figures Figure 1: Fruit tree species in Capitol Reef National Park. Figure 2: Fruit tree conditions in Capitol Reef National Park. Figure 3: Ages of the fruit trees in Capitol Reef National Park. Figure 4: Age groupings for the fruit tree species at Capitol Reef National Park. Figure 5: Percentages of historical varieties in the three general age groupings of fruit trees in Capitol Reef National Park. -

Mapping the Sensory Perception of Apple Using Descriptive Sensory Evaluation in a Genome Wide Association Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Mapping the sensory perception of apple using descriptive sensory evaluation in a genome wide association study Beatrice Amyotte1, Amy J. Bowen1, Travis Banks1, Istvan Rajcan2, Daryl J. Somers1* 1 Vineland Research and Innovation Centre, Victoria Avenue North, Vineland Station, ON, Canada, 2 University of Guelph, Department of Plant Agriculture, Guelph, ON, Canada * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 Breeding apples is a long-term endeavour and it is imperative that new cultivars are selected to have outstanding consumer appeal. This study has taken the approach of merging sen- sory science with genome wide association analyses in order to map the human perception of apple flavour and texture onto the apple genome. The goal was to identify genomic asso- OPEN ACCESS ciations that could be used in breeding apples for improved fruit quality. A collection of 85 Citation: Amyotte B, Bowen AJ, Banks T, Rajcan I, apple cultivars was examined over two years through descriptive sensory evaluation by a Somers DJ (2017) Mapping the sensory perception of apple using descriptive sensory trained sensory panel. The trained sensory panel scored randomized sliced samples of evaluation in a genome wide association study. each apple cultivar for seventeen taste, flavour and texture attributes using controlled sen- PLoS ONE 12(2): e0171710. doi:10.1371/journal. sory evaluation practices. In addition, the apple collection was subjected to genotyping by pone.0171710 sequencing for marker discovery. A genome wide association analysis suggested significant Editor: Harsh Raman, New South Wales genomic associations for several sensory traits including juiciness, crispness, mealiness Department of Primary Industries, AUSTRALIA and fresh green apple flavour. -

Best Fruit Varieties for Puget Sound Bio-Region

Best Fruit Varieties for Puget Sound Bio-region Arranged in order of maturity (Apple lists by Robert A. Norton, revised 2021 by Sam Benowitz) E=Early M=Mid L=Late (Cox) = Cox type (R) = Russet Type BEST EATERS Connoisseur's Choice: best flavored eating. Secondary factors: production, pest susceptibility, color Karmijn ML Honeycrisp EM Alkmene E (Cox) Fameuse EM Cherry Cox M (Cox) Early Fuji M Jonagold M COOK'S CHOICE Best for cooking – pie, sauce, baking, cider. Gravenstein I (problems) Bramley L Elstar EM Karmijn de Sonnaville M (Cox) Jonagold ML Belle de Boskoop L Twenty Ounce ML King L LAID-BACK ORCHARDIST Easy care; disease resistant, good yield are the primary factors. William's Pride E (gets mildew) Akane EM Ashmeads Kernal Liberty M (gets mildew) Pristine E Spartan ML Enterprise L Belmac L Centennial Crabapple VE Chehalis M (Mildew) Greensleeves M Ellison’s Orange M Bardsey L HERITAGE VARIETIES Introduced before 1920 Ashmeads Kernal M WWFRF/NW Fruit 1 Yellow Transparent E Gravenstein E King, Tompkins M Esopus Spitzenburg L Roxbury Russet VL Newtown Pippin L Brown Russet L BEST KEEPERS Early Fuji M Karmijn de Sonnaville ML (Cox) Melrose L Newton Pippin APPLES THAT RAISE A RED FLAG Gala Scab susceptible Golden Delicious Scab susceptible Red Delicious Scab susceptible Granny Smith Too late for most areas Mutsu Too late for most areas Yellow Newtown Too late for most areas Braeburn Too late for most areas Cripps Pink (Pink Lady) Too late for most areas Cox's Orange Pippin Difficult to grow – cracks, scab Ginger Gold Highly scab susceptible Goldrush Too late, shrivels, acid Northern Spy Great flavor, keeper. -

Fedco Trees 2021

Fedco Trees 2021 PO Box 520 Clinton, ME 04927 www.fedcoseeds.com (From mailing label) CC- Volume discount cutoff: Farm or Group Name January 15, 2021 Name Final order deadline: US Mail Delivery Address March 5, 2021 Town St Zip Visit fedcoseeds.com Street Address (if different) to check product Town St Zip availability. Phone Email Delivery: Substitutions: Yes No ✓ ❏ Ship in late March to mid/late April. I will accept a similar variety. ❏ ❏ Sorry, no pickup option or Tree Sale in 2021. I will accept similar rootstock. ❏ ❏ Main usors onl flara siin (Applies to apple trees only.) anno aooda si si da russ Volume Discounts: (only orders received by 1/15/21) Subtotals $100 and over take 5% off $300 and over take 10% off $600 and over take 15% off $1200 and over take 20% off Subtotal from reverse Shipping Rates Volume Discount – Maine 10 flt rte or orer 1% Fedco Member Discount from Subtotal (see back cover) – Adjusted Total Shipping Charge Continental US Up to $141.00 $22.50 Adjusted Total = (other than Maine) Over $141.00 16% of Adjusted Total Shipping + Alaska or postal Up to $125.00 $25.00 delivery required Over $125.00 20% of Adjusted Total Sales Tax + All item #s begin with L Up to $63.00 $10.00 Total = Small & Light Shipping Over $63.00 16% of Adjusted Total Donate to MeHO + Sales Tax: (Maine Heritage Orchard, see p. 14) ME addresses — Pay 5.5% sales tax on Adjusted Total Donate to Wild Seed Project (see p. 63) + MD, VA — Pay your local tax rate on Adj Total IL, IN, KY, MA, MI, MN, NC, — Shipping is taxable – pay your local Grand Total = NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, VT, WI, WV tax rate on Adj Total + Shipping • We ship via FedEx or Priority Mail, our choice.