1 Unit 4 Theories of the Origin of Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Considerations Concerning Rites of Passage and Modernity VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, Vol

VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology E-ISSN: 1809-4341 [email protected] Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasil DaMatta, Roberto Individuality and liminarity: some considerations concerning rites of passage and modernity VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, vol. 14, núm. 1, 2017, pp. 149-163 Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasília, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=406952169009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Déjà Lu Individuality and liminarity: some considerations concerning rites of passage and modernity Roberto DaMatta Departamento de Ciências Sociais, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro - PUC-RJ, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, Brazil Abstract This article explores a critical link between two concepts which are central to the social sciences: the idea of liminarity, engendered by the anthropological tradition of self-centred and self-referred monographic studies; and the idea of individuality, a key concept within the classical tradition of the socio-historical studies of great civilizations (as well as being the crucial and familiar category of our civil and political universe). The author seeks to show how a bridge can be established between these two concepts, which may at first appear distant, by focusing on certain under-discussed aspects of rites of passage. He argues that the ‘liminal’ phase of rites of passage is tied to the ambiguity brought about through the isolation and individualization of the initiate. -

Missiological Dilemma of Sorcery and Divination to African Christianity By

The Missiological Dilemma of Sorcery and Divination to African Christianity Kelvin Onongha ABSTRACT—Even after conversion to Christianity two pre-Christian practices that hold attraction to some African converts are sorcery and divination. These practices, which served a function in the lives of the people, met needs and dealt with fears in their previous lives, pose present missiological challenges to the church. This paper aims at understanding what these needs and fears are in the African experience, and to find scriptural responses that are contextually relevant while avoiding the pitfall of syncretism. Keywords: Sorcery, Divination, Worldview I. Introduction Sorcery and divination presents a serious challenge to Christian missions in the African continent. This is primarily because of the niche they fill, the function they perform, and the worldview yearnings they satisfy in the lives and experiences of the people. In order to respond to this challenge they pose, it is imperative not to merely dismiss these practices as superstitious. Rather than approaching the problem from a purely anthropological perspective, appropriate theological and missiological interventions ought to be developed to respond to this issue. This is extremely vital due to indications that there may presently exist a resurgence of these practices, even among several professed African Christians. Manuscript received Dec. 21, 2012; revised Feb. 10, 2013; accepted Feb. 15, 2013. Kelvin Onongha ([email protected]) is a post-doctoral student, and an adjunct lecturer at the Department of World Missions, Andrews University Theological Seminary, USA. AAMM, Vol. 7, 47 At a pastoral retreat a few years ago, a couple shared the story of a harrowing experience in their ministry. -

Mana Leo Project

Proposal under the Native Hawaiian Education Program CFDA Number: 84.362A United States of America Department of Education MANA LEO PROJECT Submitted By: Mana Maoli 501(c)3 1903 Palolo Ave Honolulu, HI 96816 Telephone: 808-295-626 February 11, 2020 Part 1: Forms Application for Federal Assistance (form SF 424) ED SF424 Supplement Grants.gov Lobbying Form Disclosure of Lobbying Activities U.S. Department of Education Budget Information Non-Construction Programs ED GEPA427 Form Part 2: ED Abstract Form Part 3: Application Narrative Section A - Need for Project…………………………………………………………… 1 Section B - Quality of the Project Design…………………………………………….. 6 Section C - Quality of the Project Services………………………………………….. 13 Section D - Quality of the Project Personnel…………………………………………. 17 Section E - Quality of Management Plan…………………………………………….. 21 Section F - Quality of the Project Evaluation…………………………………………. 26 Section G - Competitive Preference Priorities……………………………………….. 29 Part 4: Budget Summary and Narrative Part 5: Other Attachments Attachment A: Partner School Contributions: Summary Chart and Letters of Support Attachment B: Additional Partner Contributions: Summary Chart and Letters of Support Attachment C: Letters of Support: Charter School Commission and DOE Complex Area Superintendent Attachment D: Mana Leo Project Organization Chart Attachment E: Bios and Resumes for Key Project Staff Attachment F: Job Description for Key Project Staff Attachment G: Curriculum Summary and Sample Lessons Attachment H: Stakeholder Testimonials Attachment I: Bibliography Attachment J: Indirect Cost Rate Agreement Attachment K: Letter from LEA - Hawaii State Department of Education SECTION A - NEED FOR PROJECT “Na wai hoʻi e ʻole, he alanui i maʻa i k a he le ʻi a e oʻu mau m ākua?” – W ho s hall object t o the path I choose when it is well-traveled by my parents? S o s poke Liholiho (Kamehameha II), in a declaration that has become a prove rb for steadfast pride rooted in humility at the vastness of knowledge and accomplishments of one’s ancestors. -

THE POWER of POWDER: LIFE-FORCE and MOTILITY in CUBAN DIVINATION Martin Holbraad ANA and Transgres- Cal Propositions’ (156)

THE POWER OF POWDER: LIFE-FORCE AND MOTILITY IN CUBAN DIVINATION Martin Holbraad ANA and Transgres- cal propositions’ (156) . If mana consists of a ‘series of Such a move is possible just because the ‘universality’ concrete senses of ‘aché’ come together most clearly. sion fluid notions which merge into each other’ (134), that of mana cuts systematically across this distinction: it is Asked how aché relates to divination, babalawos’ ini- can only be because, taken in itself, it has no meaning both a thing and a concept (e.g. see Mauss 2001: 134- Along with ‘totem’ and tial response is most often that aché is the power or at all. A ‘symbol in its pure state, [and] therefore li- 5). So, the question is this. If, as was so widely com- ‘taboo’, the Ocean- capacity (in Spanish usually ‘poder’ or ‘facultad’) that able to take on any symbolic content whatever’ (Lévi- mented in the literature, mana is both, say, a stone and ian term ‘mana’ is one enables them to divine in the first place: ‘to divine Strauss 1987: 64), mana is the ‘floating signifier’ par ritual efficacy—both thing and concept, as we would of the few words to have you must have aché’, they say. In fact, conducting the excellence. In this sense, says Lévi-Strauss, terms like say—then might thinking through it provide us with crossed over from the séance, as well as other rituals, such as consecration, mana are analogous to words such as ‘thing’ or ‘stuff’ an analytical standpoint from which we would no language of ethnographic report to the vocabulary of is also said to ‘give’ the babalawo aché, which he may M – contentless forms that allow us to speak of things longer need to make this distinction? Might there be anthropological analysis – and, partly by that virtue, also ‘lose’ if he uses his office to trick people or do about which we may know little (see also Sperber a frame for analysis in which mana does not register as has also managed to lodge itself in the general lexicon gratuitous evil through sorcery. -

The Rite of Initiation in Pinter's the Birthday Party

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1978 The Rite of Initiation in Pinter's The irB thday Party Richard C. Slocum Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Slocum, Richard C., "The Rite of Initiation in Pinter's The irB thday Party" (1978). Masters Theses. 3228. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3228 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPJ<:R CERTIFICATE #Z TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved. we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because Date Author pdm THE RITE OF INITIATION IN PINTER'S THE &IRTHDAY PARTY (TITLE) BY RICHARD C. -

Navajo American Indians Through Mircea Eliade’S Theories of Time, Space and Ritual

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2013 An Analysis of the Shamanistic Healing Practices of the Navajo American Indians through Mircea Eliade’s Theories of Time, Space and Ritual John W. Wick Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Wick, John W., "An Analysis of the Shamanistic Healing Practices of the Navajo American Indians through Mircea Eliade’s Theories of Time, Space and Ritual". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2013. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/350 The telling of the Navajo creation myth begins with the appearance of the “The People” from the three underworlds and into this, the “Glittering World”, through a magic reed. Unlike human beings, “The People” were animals and masked spirits. Then came the appearance of the first man, Altse Hastiin, from the Dark World created in the east through the meeting of the white and black clouds. “The young man who walks in the darkness, may it be made as offering to him, may it be made as offering to him.” Then, Alse Asdzaa, the first woman arrives from the Dark World, made by the meeting of the yellow and blue clouds in the west. The people from the three underworlds met in the first house and began the arranging of the world. For the Navajo, this myth marks the beginning of time as they understand it and explains how the world is perceived and even lays the groundwork for ritual. -

The 'Aumakua — Hawaiian Ancestral Spirits

The ‘Aumakua — Hawaiian Ancestral Spirits by Herb Kawainui Käne Herb Kawainui Käne is an author and Pre-Christian Polynesians saw themselves a s ‘Aumakua were invisible to the living, but artist-historian with special interest in the living edge of a much greater multitude o f able to possess or inhabit many visible Hawai'i and the South Pacific. He ancestors who, as ancestral spirits, linked the forms, animate or inanimate. A rock or a resides in rural South Kona on the living to a continuum going back to the f i r s t small carved image set up in a family island of Hawaii. humans, to the major spirits, and thence to the shrine within the home might serve as a rest- ultimate male and female spirits that created ing place for ‘aumakua. The momoa, the Research on Polynesian canoes and the universe. To Polynesians there was no pointed stern of a canoe hull which projects aft voyaging led to his participation as supernatural; the entire universe and all from below the rear hull covering of a general designer and builder of the things in it, including spirits, were natural. Hawaiian canoe, was regarded as the “seat” for the invisible ‘aumakua of the canoe’s sailing canoe Höküle'a, on which he M a n a was the force that powered the uni- owner.3 The war club of a famous warrior served as its first captain. Höküle'a v e r s e – expressed in everything from the ancestor might be powered by his mana has made a number of round trip movements of stars to the growth of a plant when wielded by a descendant in battle. -

African Religions a Bibliography by Wayne Parris

39 African Religions A Bibliography By Wayne Parris 40 AFRICANUS, LEO. 1896 History and Description of Africa Done Into English by John Pory. 3 Vols. London: Hakluyt Society. 1954 Africa Today. New York: American Committee on Africa, Inc. General African history and recent socioeconomic and political matters. ANDERSSON, EFRAIM. 1958 Messianic Popular Movements in the Lower Congo. Uppsala: Studia Ethnographia Upsalensia, 14. 287 p. Study of nativistic movements in the Lower Congo areas. ARGYLE, MICHAEL. 1959 Religious Behavior. Glencoe: The Free Press. 196 p. General study of psychological elements in religion. ARKELL, A. J. 1961 A History of the Sudan. London : The Athlone Press. 225 p ARKELL, A. J. N.d. "Canes in the Tenth Century." From A History of Dafur in Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. XXXII, part ii, p. 225. Cited in Oliver, Roland and Oliver, Carolina, (ads.) Africa in the Days of Exploration. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc. 151 p. BANTON, MICHAEL. 1956 "An Independent African Church in Sierra Leone." Hibbert Journal, OV, 216. pp. 57-63. Discussion of religious acculturation and nativistic movements. BANTON, MICHAEL. 1957 West African City: A Study of Tribal Life in Freetown. London: Oxford University Press. 228 p. Study of the social characteristics of the acculturation of persons from tribal societies living in an urban center, including religious acculturation and nativistic movements. BARBER, BERNARD. 1941 "Acculturation and Messianic Movements." American Sociological Review, 6, pp. 663-69. Reprinted in Reader in Comparative Religion, Lessa and Vogt, (ads). 1965. New York: Harper and Row. pp. 506-09. Study of acculturation and nativistic movements. BARTH, HEINRICH. -

Randall Styers

February 2020 RANDALL STYERS University of North Carolina Department of Religious Studies 125 Carolina Hall, CB #3225 Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599 (919) 962-3938 [email protected] Education Duke University, Graduate Program in Religion Ph.D., Religion and Culture, 1997 Yale Divinity School M.A.R., 1984, Magna Cum Laude Yale Law School J.D., 1984 Duke University A.B. in English, 1980, Summa Cum Laude Academic Employment University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Religious Studies Associate Professor of Religion and Culture, 2007 to present Department Chair, 2013-2018 Acting Assistant Dean for Honors, Spring 2013 Bowman and Gordon Gray Distinguished Associate Professor, 2008-2013 Associate Chair, 2007-2013 Director of Graduate Studies, 2007-2013 Acting Department Chair, Fall 2008 and Fall 2011 Assistant Professor of Religion and Culture, 2001-2007 Member, Board of Governors, University of North Carolina Press, 2019 to present Department of Communication Studies, Adjunct Professor, 2009 to present Curriculum in Women's Studies, Affiliated Faculty Program in Sexuality Studies, Affiliated Faculty Union Theological Seminary, New York Acting Academic Dean, Spring 2001 Assistant Professor of the Philosophy of Religion, 1997-2001 Scholarships, Awards, and Honors Senior Faculty Research Leave, UNC Chapel Hill, Spring 2019 2 University Distinguished Teaching Award for Post-Baccalaureate Instruction, UNC Chapel Hill, 2012 Institute for the Arts and Humanities Academic Leadership Fellow, UNC Chapel Hill, 2012-2013 Office of Undergraduate Curricula Course Development Grant, UNC Chapel Hill, Summer 2006 Institute for the Arts and Humanities Spray-Randleigh Fellowship, UNC Chapel Hill, Spring 2004 University Research Council Grant, UNC Chapel Hill, Summer 2003 Spray-Randleigh Research Fellowship, UNC Chapel Hill, Summer 2002 Williamson Course Development Grant, UNC Chapel Hill, Summer 2002 National Endowment for the Humanities Dissertation Grant, 1995-96 Honorary Charlotte W. -

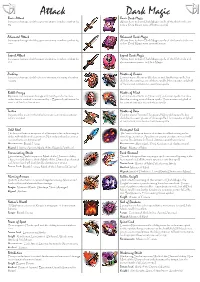

Attack Dark Magic

Attack DarkDark MagicMagic Basic Attack Basic Dark Magic Increases damage dealt by your creatures in melee combat by AllowsAllows hheroero ttoo llearnearn DarkDark MagicMagic spellsspells ofof thethe thirdthird circlecircle andand 5%. makesmakes DarkDark MagicMagic moremore effectiveeffective overall.overall. Advanced Attack Advanced Dark Magic Increases damage dealt by your creatures in melee combat by AllowsAllows hheroero ttoo llearnearn DarkDark MagicMagic spellsspells ofof thethe fourthfourth circlecircle andand 10%. makesmakes DarkDark MagicMagic eveneven moremore effective.effective. Expert Attack Expert Dark Magic Increases damage dealt by your creatures in melee combat by AllowsAllows hheroero ttoo llearnearn DarkDark MagicMagic spellsspells ofof thethe fifthfifth circlecircle andand 15%. givesgives maximummaximum powerpower toto DarkDark Magic.Magic. Archery Master of Curses IncreasesIncreases damagedamage dealtdealt byby hero’shero’s creaturescreatures inin rangedranged combatcombat GrantsGrants mmassass effectseffects toto WeaknessWeakness andand SSufferinguffering spells,spells, butbut by 20%. doublesdoubles thethe castingcasting costcost ofof thesethese spells.spells. HeroHero wasteswastes onlyonly halfhalf ofof hishis currentcurrent initiativeinitiative toto castcast thesethese spellsspells Battle Frenzy Master of Mind MinimumMinimum andand maximummaximum damagedamage inflictedinflicted byby eacheach creaturecreature GrantsGrants mmassass effectseffects toto SlowSlow andand ConfusionConfusion spells,spells, butbut dou-dou- -

INTRODUCTION: “Religion” Has an Inherent and Unchanging Meaning

INTRODUCTION: “Religion” has an inherent and unchanging meaning; it has suggested the pursuit of the Holy Grail, an unending quest for a desirable something lying perpetually in the distance. A religion is an organized collection of beliefs, cultural systems, world views that relate humanity to an order of existence. Many religions have narrative, symbols and sacred histories that aim to explain the meaning of life, or the universe. From their beliefs about the cosmos and human nature, people may derive morality, ethics, religious laws or a preferred life style. Anthropologists have commonly called religion a “cultural universe”, one of the many things, including marriage, incest prohibitions, the family, and the social organization, found everywhere in the world. No society ever observed has failed to display something readily identifiable to scholars as religion. Magic is the use of rituals, symbols, actions, gestures and language that are believed to exploit supernatural forces. The belief in and the practice of magic has been present since the earliest human cultures and continues to have an important spiritual, religious and medicinal role in many cultures today. 1. DEFINITION OF RELIGION: According to the philologists Max Muller, “the root of the English word “religion”, the Latin “religo”, was originally used to mean only reverence for God or the Gods, carefully pondering of divine things, piety” The typical dictionary definition of religion refers to a “belief in, or the worship of , a God or Gods” or the “Service and worship of God or the supernatural.” Edward Burnett Tylor defined religion as “the belief in spiritual being”. The anthropologist Clifford Greetz defined religion as a “ system of symbol which acts to establish powerful pervasive, and long lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing, these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic”. -

Mana, Power and 'Pawa' in the Pacific and Beyond

5 Mana, Power and ‘Pawa’ in the Pacific and Beyond Alan Rumsey In this chapter I address three interrelated topics pertaining to mana and how it might be understood in relation to ‘power’ as a social- analytical construct, and to pawa as a vernacular term used by some Pacific peoples. First, I briefly review the history of anthropological and comparative- linguistic understandings of mana, from Robert Codrington’s boldly speculative account (1891), to Raymond Firth’s (1940) much more cautious one, to Roger Keesing’s (1984) argument concerning what he takes to be western misconstruals of traditional concepts of mana held by Pacific peoples speaking Oceanic Austronesian languages. I offer some caveats about that argument and update it by reviewing some more recent work by other scholars who have tried to link those words and concepts to others that are attested in Austronesian languages across a wider region than Oceania, and even to Papuan languages extending into the interior of Papua New Guinea (PNG). Next, turning to my field experience in PNG among speakers of a Papuan language who do not have a word like mana that is used in anything very close to the senses that that word has in Oceanic languages, I discuss the word that they use that comes closest to those senses, namely pawa, a word that has come into the Ku Waru language 131 NEW MANA through borrowing from Tok Pisin, but is nowadays very frequently used by people when speaking Ku Waru as the main noun for ‘power’, in close relation to an inherited Ku Waru word (todul) meaning ‘strong’.