Before the Football Association Premier League Arbitral Tribunal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greatest Escape the Craziest Season in West Ham United’S History

Title information The Greatest Escape The Craziest Season in West Ham United’s History The By Daniel Hurley The Craziest Season in West Ham United’s History United’s Ham West in Season Craziest The Do Cheats Sometimes Prosper? Sometimes Do Cheats Greates Key features • First deep-dive examination of the 2006/07 season; the book does not exclusively focus on the controversy around The the signings of Tevez and Mascherano T • Written by a lifelong West Ham United fan and season- e GreatesT ticket holder who witnessed the season first hand scape escape • Author forensically examines the complete transfer saga, The Craziest Season in against the backdrop of a chaotic period in the club’s history West Ham United’s History • Includes new insight via interviews with key individuals connected to the story – including players, staff, journalists, commentators, pundits and fans DANIEL HURLEY • Colour photo section of players and matches covered • Publicity campaign planned including radio, newspapers, websites, podcasts and magazines Description As a football fan, there are those seasons which remain indelibly inscribed in the memory. Simply unforgettable. The 2006/07 season remains one of those for fans of West Ham United. A season that began with such promise: Alan Pardew signed two genuine world- class players ahead of the kick-off, but little did the Argentinian pair of Carlos Tevez and Javier Mascherano know they joined a season- long relegation battle. Roll forward to the business end, and with nine matches left to play the Hammers looked doomed. Seven wins from those nine made it arguably the greatest escape in English top-flight history. -

Corporate Days Con Javier Mascherano Programas De Tv Y Radio

JAVIER MASCHERANO Javier Mascherano, el jefecito. Conocido por haber vestido algunas camisetas de los clubes más grandes del mundo y por su destacado desempeño en su posición de pivote, como un recuperador nato, un escudo del medio campo y su liderazgo dentro y fuera de la cancha. Se trata del jugador que más veces ha vestido la elástica albiceleste en la historia. Además, tuvo el honor de ser el capitán de la Selección Nacional Argentina durante el periodo comprendido entre 2008 y 2011 donde mostró sus dotes de liderazgo. Inició su carrera como profesional en River Plate de Argentina, y más tarde jugó en el S.C. Corrinthians. Después emprendió su camino a Europa jugando con el West Ham United y después con Liverpool. Posteriormente jugó en el FC Barcelona donde conquistó, en sus ocho temporadas, cinco títulos de liga, dos Champions League, cinco ediciones de la Copa del Rey, tres Supercopas de España, dos Supercopa de Europa y dos ediciones del Mundial de Clubes. Tuvo un paso el Hebei Fortune de China y actualmente juega en Estudiantes De La Plata. VALORES DE MASCHERANO Trabajador Profesional Líder motivador Responsable Experimentado Fuerza Alegre Resistencia Luchador Comprometido Resiliente PROFESIONAL CONCEPTUAL SOCIAL PERSONAL Deportista Trabajador Familiar Cercano Comprometido Divertido Familiar Argentino AUDIENCIA EN REDES 5,3 8,1 4,4 MILLONES MILLONES MILLONES 17,8 MILLONES AUDIENCIA TOTAL CONTENIDO EN SUS REDES Su entrenamiento diario, Humano, cercano, su riguroso trabajo y familiar entrega hacia su profesión Destaca su paso por la selección, recordando partidos, fechas importantes y logros. Mantiene el vínculo con los clubes en los que ha jugado felicitándolos, y recordando sus logros. -

Soccernews Issue # 07, July 10Th 2014

SoccerNews Issue # 07, July 10th 2014 Continental/Division Tires Alexander Bahlmann Phone: +49 511 938 2615 Head of Media & Public Relations PLT E-Mail: [email protected] Buettnerstraße 25 | 30165 Hannover www.contisoccerworld.de SoccerNews # 07/2014 2 World Cup insight German team watched the match at their base camp in South Bahia, where they had been celebrated by the locals upon their return. (Video-Link Süddeutsche Zeitung: Final countdown http://www.sueddeutsche.de/sport/herzlicher- empfang-trotz-1.2037941). The 23 players and is running for the the coaching staff headed by Joachim Loew watched how two-time World Cup champions Argentina positively toiled to reach the final. DFB team The match in no way reached the level of the semi-final in Belo Horizonte on the previous After the magical night with the historic 7-1 evening, acclaimed around the globe, when triumph over Brazil, Argentina is the last ob- the German national team achieved a sen- stacle on the road to the fourth World Cup sational, unique triumph over the World Cup title for the German national team. In the hosts. Brazil and the Netherlands will meet in disappointingly colourless second semi-final the “small final” for third place in the capital of the 2014 FIFA World Cup™, the Argentinians Brasilia (22:00hrs CSET), a fixture won by The national team and captain Philipp Lahm after the historic triumph against Brazil defeated the Netherlands 4-2 in a penalty the DFB team in 2006 (against Portugal) and shoot-out after 120 goalless minutes in Sao 2010 (against Uruguay). -

2016 Panini Flawless Soccer Cards Checklist

Card Set Number Player Base 1 Keisuke Honda Base 2 Riccardo Montolivo Base 3 Antoine Griezmann Base 4 Fernando Torres Base 5 Koke Base 6 Ilkay Gundogan Base 7 Marco Reus Base 8 Mats Hummels Base 9 Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang Base 10 Shinji Kagawa Base 11 Andres Iniesta Base 12 Dani Alves Base 13 Lionel Messi Base 14 Luis Suarez Base 15 Neymar Jr. Base 16 Arjen Robben Base 17 Arturo Vidal Base 18 Franck Ribery Base 19 Manuel Neuer Base 20 Thomas Muller Base 21 Fernando Muslera Base 22 Wesley Sneijder Base 23 David Luiz Base 24 Edinson Cavani Base 25 Marco Verratti Base 26 Thiago Silva Base 27 Zlatan Ibrahimovic Base 28 Cristiano Ronaldo Base 29 Gareth Bale Base 30 Keylor Navas Base 31 James Rodriguez Base 32 Raphael Varane Base 33 Karim Benzema Base 34 Axel Witsel Base 35 Ezequiel Garay Base 36 Hulk Base 37 Angel Di Maria Base 38 Gonzalo Higuain Base 39 Javier Mascherano Base 40 Lionel Messi Base 41 Pablo Zabaleta Base 42 Sergio Aguero Base 43 Eden Hazard Base 44 Jan Vertonghen Base 45 Marouane Fellaini Base 46 Romelu Lukaku Base 47 Thibaut Courtois Base 48 Vincent Kompany Base 49 Edin Dzeko Base 50 Dani Alves Base 51 David Luiz Base 52 Kaka Base 53 Neymar Jr. Base 54 Thiago Silva Base 55 Alexis Sanchez Base 56 Arturo Vidal Base 57 Claudio Bravo Base 58 James Rodriguez Base 59 Radamel Falcao Base 60 Ivan Rakitic Base 61 Luka Modric Base 62 Mario Mandzukic Base 63 Gary Cahill Base 64 Joe Hart Base 65 Raheem Sterling Base 66 Wayne Rooney Base 67 Hugo Lloris Base 68 Morgan Schneiderlin Base 69 Olivier Giroud Base 70 Patrice Evra Base 71 Paul -

Rafael Benitez on World Cup 2014: Never Mind Neymar – Argentina Will Feel Loss of Free-Running Angel Di Maria Against Netherlands

Rafael Benitez on World Cup 2014: Never mind Neymar – Argentina will feel loss of free-running Angel Di Maria against Netherlands In his exclusive column for The Independent, the former Liverpool manager and current Napoli boss warns that the Netherlands shouldn't underestimate Argentina's tactical flexibility during their semi-final meeting Rafael Benitez Tuesday, 8 July 2014 We have heard a lot about the Brazilian favelas and Argentina has its special difficult conditions too. They call them the potreros. It is where they play football, normally on small pieces of land – irregular – and it is because of the difficulties that the players look for football to give them a way out. Don’t underestimate how the poverty has given Argentina the players it has. I have known a lot of them and I know that with Argentina there is a spirit which few other nations have. They have a very tough job now that we are into the last week of the tournament. Everyone has been talking about Neymar in the last three days but Argentina losing Angel Di Maria has consequences which could be just as serious – maybe we can say more serious – than Brazil losing their talisman. I’m talking about options. We have seen Alejandro Sabella, the Argentina manager, being very flexible with his tactics in the tournament. He started with a line of five in midfield in the first half of the first game against Bosnia. Then he went to 4-3-1-2, then 4-2-3-1, with Lionel Messi behind Gonzalo Higuain, my striker at Napoli, Di Maria on the right and Ezequiel Lavezzi the left – giving width. -

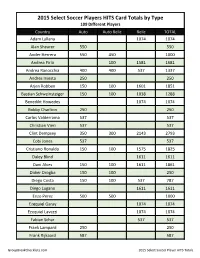

2015 Select Soccer Team HITS Checklist;

2015 Select Soccer Players HITS Card Totals by Type 109 Different Players Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Adam Lallana 1074 1074 Alan Shearer 550 550 Ander Herrera 550 450 1000 Andrea Pirlo 100 1581 1681 Andrea Ranocchia 400 400 537 1337 Andres Iniesta 250 250 Arjen Robben 150 100 1601 1851 Bastian Schweinsteiger 150 100 1038 1288 Benedikt Howedes 1074 1074 Bobby Charlton 250 250 Carlos Valderrama 537 537 Christian Vieri 537 537 Clint Dempsey 350 300 2143 2793 Cobi Jones 537 537 Cristiano Ronaldo 150 100 1575 1825 Daley Blind 1611 1611 Dani Alves 150 100 1611 1861 Didier Drogba 150 100 250 Diego Costa 150 100 537 787 Diego Lugano 1611 1611 Enzo Perez 500 500 1000 Ezequiel Garay 1074 1074 Ezequiel Lavezzi 1074 1074 Fabian Schar 537 537 Frank Lampard 250 250 Frank Rijkaard 587 587 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2015 Select Soccer Player HITS Totals Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Franz Beckenbauer 250 250 Gerard Pique 150 100 1601 1851 Gervinho 525 475 1611 2611 Gianluigi Buffon 125 125 1521 1771 Guillermo Ochoa 335 125 1611 2071 Harry Kane 513 503 537 1553 Hector Herrera 537 537 Hugo Sanchez 539 539 Iker Casillas 1591 1591 Ivan Rakitic 450 450 1024 1924 Ivan Zamorano 537 537 James Rodriguez 125 125 1611 1861 Jan Vertonghen 200 150 1074 1424 Jasper Cillessen 1575 1575 Javier Mascherano 1074 1074 Joao Moutinho 1611 1611 Joe Hart 175 175 1561 1911 John Terry 587 100 687 Jordan Henderson 1074 1074 Jorge Campos 587 587 Jozy Altidore 275 225 1611 2111 Juan Mata 425 375 800 Jurgen Klinsmann 250 250 Karim Benzema 537 537 Kevin Mirallas 525 475 -

Mascherano Impressed with Qatar's 'Compact' WC Concept, Future Plans

SPORT SPORT | 18 SPORT | 19 MotoGP: Archer available Quartararo storms for third Test to pole in match against season-opener West Indies SUNDAY 19 JULY 2020 'Fans will have an easy time commuting for Qatar 2022 matches' Mascherano impressed with Qatar’s ‘compact' WC concept, future plans CHINTHANA WASALA Generation Amazing’s (@ THE PENINSULA GA4Good)GA4Good) InstagramInstagram LiveLive sessionsession whichwhich waswas arrangedarranged inin Players and fans havinghaving to collaborationcollaboration withwith the travel short distancess ffromrom oonene ArgentinaArgenttina EmbassyEmbasssy inn QatarQatar andandd stadium to another foror matchesmatches thethe AmbassadorAmbbaassaddor H E Dr CarlosCarlos I have a good at the Qatar 2022 WorldWorld CupCup Hernandez.Heernaandez. friend in Doha, would prove to be a 'f'fabulous'abulous' MascheranoMascheranno mademadde 1471447 Xavi. We have concept, Barcelona andand Argen-Argen- appearancesappearances forfofor thethe ArgentinaArArgeentini a tinian legend Javier MascheranoMascheranoo nationalnationall teamteaeam duringduurir ng hishis discussed a lot of said. 15-year15-yeaar internationalinntternational careercaarereere youth development Argentina’s mostst cappedcappeed sincesince hishiis ddedebutbut in 2002003.3. HHee projects with Xavi, national player, a two-timetwo-timme representedreprresseenntted the nationnation who is now a Global Olympic gold medallist,medallisst, at fivefivve CopaCopa Ambassador for SC. Mascherano praiseded Qatar’sQataarr’s AméricaAmmérica tour-toouurr- When I was in Doha -

Futera World Football Online 2010 (Series 2) Checklist

www.soccercardindex.com Futera World Football Online 2010 (series 2) checklist GOALKEEPERS 467 Khalid Boulahrouz 538 Martin Stranzl 606 Edison Méndez 674 Nihat Kahveci B R 468 Wilfred Bouma 539 Marcus Tulio Tanaka 607 John Obi Mikel 675 Salomon Kalou 401 René Adler 469 Gary Caldwell 540 Vasilis Torosidis 608 Zvjezdan Misimovic 676 Robbie Keane 402 Marco Amelia 470 Joan Capdevila 541 Tomas Ujfalusi 609 Teko Modise 677 Seol Ki-Hyeon 403 Stephan Andersen 471 Servet Çetin 542 Marcin Wasilewski 610 Luka Modric 678 Bojan Krkic 404 Árni Arason 472 Steve Cherundolo 543 Du Wei 611 João Moutinho 679 Gao Lin 405 Diego Benaglio 473 Gaël Clichy 544 Luke Wilkshire 612 Kim Nam-Il 680 Younis Mahmoud 406 Claudio Bravo 474 James Collins 545 Sun Xiang 613 Nani 681 Benni McCarthy 407 Fabian Carini 475 Vedran Corluka 546 Cao Yang 614 Samir Nasri 682 Takayuki Morimoto 408 Idriss Carlos Kameni 476 Martin Demichelis 547 Mario Yepes 615 Gonzalo Pineda 683 Adrian Mutu 409 Juan Pablo Carrizo 477 Julio Cesar Dominguez 548 Gokhan Zan 616 Jaroslav Plašil 684 Shinji Okazaki 410 Julio Cesar 478 Jin Kim Dong 549 Cristian Zapata 617 Jan Polak 685 Bernard Parker 411 José Francisco Cevallos 479 Andrea Dossena 550 Marc Zoro 618 Christian Poulsen 686 Roman Pavlyuchenko 412 Konstantinos Chalkias 480 Cha Du-Ri 619 Ivan Rakitic 687 Lukas Podolski 413 Volkan Demirel 481 Richard Dunne MIDFIELDERS 620 Aaron Ramsey 688 Robinho 414 Eduardo 482 Urby Emanuelson B R 621 Bjørn Helge Riise 689 Hugo Rodallega 415 Austin Ejide 483 Giovanny Espinoza 551 Ibrahim Afellay 622 Juan Román Riquelme -

Full Time Report LIVERPOOL FC REAL MADRID CF

Full Time Report First Knock-out Round 2nd leg - Tuesday 10 March 2009 Anfield - Liverpool LIVERPOOL FC 11st leg 0 REAL MADRID CF LIVERPOOL FC win 5-0 on aggregate 420:45 0 (2) (0) half time half time 9 Fernando Torres 16' 19' 3 Pepe 25 Pepe Reina 1 Iker Casillas 8 Steven Gerrard 3 Pepe 9 Fernando Torres 8 Steven Gerrard 26' 4 Sergio Ramos 12 Fábio Aurélio 5 Fabio Cannavaro 14 Xabi Alonso 8 Steven Gerrard 28' 27' 16 Gabriel Heinze 7 Raúl González 17 Álvaro Arbeloa 8 Fernando Gago 18 Dirk Kuyt 10 Wesley Sneijder 19 Ryan Babel 11 Arjen Robben 20 Javier Mascherano 16 Gabriel Heinze 23 Jamie Carragher 20 Gonzalo Higuaín 37 Martin Škrtel 39 Lassana Diarra 20 Javier Mascherano 43' 1 Diego Cavalieri 25 Jerzy Dudek 2 Andrea Dossena 9 Javier Saviola 4 Sami Hyypiä 12 Marcelo 21 Lucas 45' 14 Guti 24 David N'Gog 2'05" 21 Christoph Metzelder 26 Jay Spearing 22 Miguel Torres 34 Martin Kelly 23 Rafael van der Vaart in 12 Marcelo 8 Steven Gerrard 47' 46' Coach: out 11 Arjen Robben Coach: Rafael Benítez Juande Ramos Full Full Half Half Total shot(s) 10 16 Total shot(s) 7 15 Shot(s) on target 7 12 Shot(s) on target 3 3 Free kick(s) to goal 1 1 21 Lucas in Free kick(s) to goal 1 2 14 Xabi Alonso out 60' 62' 12 Marcelo Save(s) 3 4 in 23 Rafael van der Vaart Save(s) 5 8 Corner(s) 5 10 64' out 5 Fabio Cannavaro Corner(s) 1 4 Foul(s) committed 15 26 Foul(s) committed 11 15 Foul(s) suffered 9 13 Foul(s) suffered 15 25 Offside(s) 2 5 Offside(s) 1 2 Possession 50% 44% Possession 50% 56% Ball in play 13'14" 24'59" 26 Jay Spearing in Ball in play 13'57" 31'08" out -

Pele-Like Mbappe Strikes Send Messi, Argentina Crashing Out

SUNDAY, JULY 1, 2018 20 French revolution Pele-like Mbappe strikes send Messi, Argentina crashing out AFP | Russia by Marcos Rojo. Antoine Griez- he was played into the area, mann coolly converted the 13th were waved away. France had eenage star Kylian minute penalty. But Mbappe’s looked in control, but the stakes ly-struck Mbappe struck twice and PSG teammate Angel Di Maria changed dramatically minutes half-volley Tearned another goal as levelled with a 41st minute long- before the interval. with the out - France finally found their at- range stunner and the South Cristian Pavon, on the left side of his right tacking edge to beat Lionel Mes- Americans were back in what flank, found Di Maria unmarked boot that spun past si’s Argentina 4-3 and move into was proving a superb match. 25 yards out from goal and he Argentina ‘keeper the quarter-finals of the World Argentina took a 2-1 lead min- unleashed a thunderbolt that Franco Armani af - ter Cup yesterday. utes after the restart when Ga- flew past a diving Lloris and into Blaise Matuidi’s wayward cross Billed as Messi’s chance to briel Mercado clipped Messi’s the top right-hand corner. found the Stuttgart defender. reignite stuttering Argentina’s low curling shot past Hugo Llo- Di Maria, one of several Al- Despite a late consolation for hopes, the thrilling last 16 clash ris, but that was Messi’s only real biceleste players criticised for Argentinan when Sergio Ague- in Kazan instead saw 19-year- contribution in the match. -

Kandidatenliste FIFA/Fifpro World XI 2010

Kandidatenliste FIFA/FIFPro World XI 2010 Torhüter Name Land Klub Alter Gianluigi Buffon Italy Juventus FC 32 Iker Casillas Spain Real Madrid C.F. 29 Petr Cech Czech Republic Chelsea FC FC 28 Julio César Brazil F.C. Internazionale 31 Manchester United FC Edwin van der Sar Netherlands 40 FC 1 Verteidiger Name Land Klub Alter Ashley Cole England Chelsea FC 30 Daniel Alves Brazil FC Barcelona 27 Gareth Bale Wales Tottenham Hotspur 21 Michel Bastos Brazil Olympique Lyon 27 Patrice Evra France Manchester United FC 29 Rio Ferdinand England Manchester United FC 32 Philipp Lahm Germany FC Bayern München 27 Lúcio Brazil F.C. Internazionale 32 Maicon Brazil F.C. Internazionale 29 Marcelo Brazil Real Madrid C.F. 22 Alessandro Nesta Italy AC Milan 34 Pepe Portugal Real Madrid C.F. 27 Gerard Pique Spain FC Barcelona 23 Carles Puyol Spain FC Barcelona 32 Sergio Ramos Spain Real Madrid C.F. 24 Walter Samuel Argentina F.C. Internazionale 32 John Terry England Chelsea FC 30 Thiago Silva Brazil AC Milan 26 Nemanja Vidic Serbia Manchester United FC 29 Javier Zanetti Argentina F.C. Internazionale 37 2 Mittelfeldspieler Name Land Klub Alter Esteban Cambiasso Argentina F.C. Internazionale 30 Michael Essien Ghana Chelsea FC 28 Cesc Fàbregas Spain Arsenal FC 23 Steven Gerrard England Liverpool FC 30 Andrés Iniesta Spain FC Barcelona 26 Kaká Brazil Real Madrid C.F. 28 Frank Lampard England Chelsea FC 32 Javier Mascherano Argentina FC Barcelona 26 Thomas Müller Germany FC Bayern München 21 Mesut Özil Germany Real Madrid C.F. 22 Andrea Pirlo Italy AC Milan 31 Bastian Germany FC Bayern München 26 Schweinsteiger Wesley Sneijder Netherlands F.C. -

Panini Super Strikes Champions League 2009/2010

www.soccercardindex.com Panini Super Strikes Champions League 2009/10 checklist AC Milan 51 Florent Malouda 102 Bojan Krkic 152 Samuel Eto'o 1 Christian Abbiati 52 Frank Lampard 103 Thier Henry 153 Mario Balotelli 2 Alessandro Nesta 53 Salomon Kalou 104 Lionel Messi (C) 154 Diego Milito 3 Thiago Silva 54 Daniel Sturridge 105 Andrés Iniesta (C) 155 Maicon (C) 4 Gianluca Zambrotta 55 Nicolas Anelka 106 Carles Puyol (FF) 156 Samuel Eto'o (C) 5 Andrea Pirlo 56 Didier Drogba 107 Victor Valdés (GS) 157 Javier Zanetti (FF) 6 Massimo Ambrosini 57 John Terry (C) 108 Zlatan Ibrahimovic (SP) 158 Julio César (GS) 7 Mathieu Flamini 58 Didier Drogba (C) 109 Xavi Hemandez (SP) 159 Esteban Cambiasso 8 Gennaro Gattuso 59 John Terrry (FF) 160 Lucio (SP) 9 Clarence Seedorf 60 Frank Lampard (FF) FC Bayern München 10 Ronaldinho 61 Petr Cech (GS) 110 Michael Rensing Porto 11 Filippo Inzaghi 62 Michael Essien (SP) 111 Edson Braafheid 161 Helton 12 Alexandre Pato 63 Nicolas Anelka (SP) 112 Martin Demichelis 162 Bruno Alves 13 Ronaldinho (C) 113 Philip Lahm 163 Jorge Fucile 14 Pato (C) PFC CSKA Moskva 114 Daniel van Buyten 164 Rolando 15 Gennaro Gattuso (FF) 64 Igor Akinfeev 115 Anatoli Tymoshchuk 165 Raul Meireles 16 Christian Abbiati (GS) 65 Sergei Ignashevich 116 Danijel Pranijc 166 Mariano Gonzalez 17 Andrea Pirlo (SP) 66 Deividas Semberas 117 Mark van Bommel 167 Femando Belluschi 67 Evgeni Aldonin 118 Bastian Schweinsteiger 168 Radamel Falcao AZ Alkmaar 68 Daniel Carvalho 119 Franck Ribéry 169 Hulk 18 Sergio Romero 69 Milos Krasic 120 Hamit Altintop 170