14 Fake Alignments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAACP National Board Makes Dramatic Move to Regain Relevance

www.lasentinel.net Congratulations Dr. Danny J. Bakewell, Sr. An Education Giant Succumbs - Judy Ivie (See page A-3) Burton (See page A-13) VOL. LXXXI NO. 21 $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax “For Over Eighty Years, The Voice of Our Community Speaking for Itself” THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER MAY 25,17, 20172015 ALLISON SHELLEY/TV ONE Marc Morial, National Urban League president/CEO SENTINEL NEWS SERVICE decades, The State of Black America®, has For the first time become one of the in Urban League his- most highly-anticipated tory, its annual State of benchmarks and sources Black America report for thought leadership is the basis for a nation- around racial equality in ally-televised special. America across econom- Moderated by News ics, employment, edu- One Now Host and Man- cation, health, housing, aging Editor Roland criminal justice and civic FREDDIE ALLEN/AMG/NNPA Martin, “National Urban participation,” National Cornell Brooks served as president of the NAACP for three years. This photo was taken during a 2016 meeting be- League Presents: State of Urban League President tween civil right leaders and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Black America® Town and CEO Marc H. Mo- Hall” was produced in rial said. “Now, thanks NAACP National Board Makes Dramatic Move to Regain Relevance partnership with TV to TV One and our other One and premieres on partners, we’re thrilled BY LAUREN VICTORIA BURKE national board vote to part contacted by the NNPA tion since May 2014. Some the network Wednesday, to be able to bring the NNPA Newswire Contributor ways with their president, Newswire were shocked NAACP insiders said that May 31 at 8 p.m. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Remarks in a Meeting With

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Remarks in a Meeting With African American Leaders and an Exchange With Reporters February 27, 2020 The President. Well, I want to thank you very much. We're here with some of the Black leaders of our country and people that are highly respected and people that have done a fantastic job and, for the most part, have been working on this whole situation with me right from the beginning. Participants. Yes. Yes. The President. And we've done a lot. We've done Opportunity Zones. We've done criminal justice reform. We've done things that people didn't even think possible. Criminal justice reform—we've let a lot of great people out of jail. Participants. Yes! [Applause] The President. And you know, Alice Johnson is, really, just such a great example. A fine woman. And she doesn't say she didn't do it; she made a mistake. But she was in there for 22 years when we let her out, and she had practically another 20 left. Participant. She did. The President. And that's not appropriate. Alveda King Ministries Founder Alveda C. King. Her children grew up, her grandbabies. The President. Yes, I know. So incredible. And you couldn't produce—there's nobody is Hollywood that could have produced that last scene of her. Ms. King. Amen. Amazing. The President. That was the real deal—of her when she saw her kids. So it's really a fantastic thing. So what I think I do is I'd like to—for the media, I'd like to go around the room, and we can do just a quick introduction of each other. -

PG Post 03.31.05 Vol.73#13F

The Pri nce Ge orge’s Pos t A C OMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FOR PRINCE GEORGE ’S COUNTY Since 1932 Vol. 76, No. 4 January 24 — January 30, 2008 Prince George’s County, Maryland Newspaper of Record Phone: 301-627-0900 25 cents State Officials Grapple MD Kids With Foreclosure Crisis Have By LAURA SCHWARTZMAN Maryland had 6,969 foreclo - to keep their houses. Capital News Service sures in October and November Foreclosure spikes across Lowest 2007 alone, said Department of the country are the fallout from ANNAPOLIS - A dramatic Labor, Licensing and a boom in subprime lending rise in foreclosures and related Regulation Secretary Thomas where borrowers were offered Poverty scams is expected in Maryland Perez, in a briefing this week loans beyond their means, said in the coming year, prompting before the House Economic Bruce Marks, chief executive Fewer Maryland the governor and the General Matters Committee. The fore - officer of the Boston-based Assembly to roll out several closure rate statewide increased Neighborhood Assistance Children Under initiatives intended to help peo - by 639 percent between the Corporation of America. The Five Are Poor ple keep their homes and avoid third quarter of 2006 and the loans quickly became unafford - mortgage fraud. third quarter of 2007, he said. able and homeowners lost their By BEN MEYERSON Gov. Martin O’Malley this Foreclosures not only hurt houses. Capital News Service the individual homeowners, “These mortgages were week proposed a set of emer - WASHINGTON - Maryland they also affect the state’s tax structured to fail,” he said. gency regulatory reforms and had the lowest percentage of revenue, further straining an Several of O’Malley’s emer - bills to target predatory lending children younger than 5 living already tight budget situation. -

2016 Annual Report of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund (TMCF)

TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME LETTER 1 SCHOLARSHIPS 2 PROGRAMS 4 CAPACITY BUILDING 20 SCHOOL SUPPORT REPORT 22 PUBLIC POLICY & ADVOCACY 23 SPECIAL EVENTS 25 IN THEIR OWN WORDS 31 DONOR LISTING 33 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 37 EXECUTIVE TEAM 38 STAFF DIRECTORY 39 MEMBER-SCHOOLS 40 FINANCIALS 41 TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME LETTER Dear Friends, Thank you for taking the time to review the 2016 Annual Report of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund (TMCF). The data included will provide you with a high-level review of TMCF’s accomplishments in 2016—fulfi lling our vision of Changing the World... One Leader at a Time. TMCF’s growth and presence over the years make me proud of the work we do daily to support our member-schools and assist them with preparing our students to be the next generation of leaders. However, even though we had an incredible year, there is so much more to be done. There are so many more students who need an opportunity o ered, encouragement given, or an obstacle removed in order to achieve their full potential. Even though we do the work, we are keenly aware that nonprofi ts need partners to help develop creative solutions to get and stay on the path to sustainability. And, we’re deeply proud of the community of donors, partners, and supporters who work with us to make this happen. As we prepare for our 30th anniversary next year, we will remain dedicated to ensure that the success of member-schools and students will continue to grow. Our ultimate goal is for TMCF to be the fundamental place WHERE EDUCATION PAYS OFF®. -

Memorial Day Weekend Draws Both Crowds and Crime from Gun Fire on Daytona Beach to KMOV-TV Reported

Volume 97 Number 41 | MAY 27-JUNE 2, 2020 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross funds Miami Gardens Food Relief Program. PENNY DICKERSON [email protected] ood scarcity and job loss in the city of Miami Gardens is being aggressively addressed through a multi-million dollar partnership announced May 26 and funded by Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross and the Miami Dolphins Foundation. The Miami Dolphins Food Relief Program is scheduled to launch June 1 and will pro- videF a minimum of 1,000 meals to families in need through a voucher system — Monday thru Friday out of Hard Rock Stadium. The initiative is expected to last one year, and meals will be prepared by Centerplate, the team’s food, beverage and retail partner. Photo: The Miami Dolphins On Sundays, the Dol- worldwide for a potential The Miami Dolphins Food Relief Program is scheduled to launch June 1 and will phins will partner with the $4 million total impact. faith-based community The economic toll of provide a minimum of 1,000 meals to families in need through a voucher system including area churches, the COVID-19 pandemic — Monday thru Friday, out of Hard Rock Stadium. The initiative is expected to last local leadership, and created a food crisis that one year, and meals will be prepared by Centerplate, the team’s food, beverage community groups to spared no socioeconomic and retail partner. purchase food from local class level. From unem- restaurants to provide a ployment to the sudden minimum of 1,000 meals transition of households We are committed to com- each Sunday that will be with children home from distributed to those deal- school during the day and bating food insecurity and ing with food insecurity. -

June 20, 2019 the Honorable Henry Kerner Special Counsel Office Of

June 20, 2019 The Honorable Henry Kerner Special Counsel Office of Special Counsel 1730 M Street, N.W. Suite 218 Washington, D.C. 20036-4505 Re: Violation of the Hatch Act by Ivanka Trump Dear Mr. Kerner: Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (“CREW”) respectfully requests that the Office of Special Counsel (“OSC”) investigate whether Assistant to the President Ivanka Trump violated the Hatch Act by using her social media account, @IvankaTrump, to post messages including President Trump’s campaign slogan “Make America Great Again.” These actions were directed specifically toward the success or failure of Donald J. Trump, a candidate in a partisan election. By sharing these posts on a Twitter account that Ms. Trump uses for official government business, Ms. Trump engaged in political activity prohibited by law. Factual Background Ms. Trump was appointed to be Assistant to President Trump in March 2017.1 In this capacity, Ms. Trump serves as an “unpaid advisor to her father in the White House.”2 In response to nepotism and other ethical questions raised following her appointment, Ms. Trump issued a statement, saying: I have heard the concerns some have with my advising the president in my personal capacity while voluntarily complying with all ethics rules, and I will instead serve as an unpaid employee in the White House Office, subject to all of the same rules as other federal employees.3 Ms. Trump uses the Twitter handle @IvankaTrump and identifies herself on that social media platform as “Advisor to POTUS on job creation + economic empowerment, workforce development & entrepreneurship.”4 Since joining the Trump Administration, Ms. -

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report July 1- September 30,2016 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA-K227BX-K210AD S

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report July 1- September 30,2016 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA-K227BX-K210AD START TIME DURATION ISSUE TITLE AND NARRATIVE 7/1/2016 Take Two: Border Patrol: Yesterday, for the first time, the US Border patrol released the conclusions of that panel's investigations into four deadly shootings. Libby Denkmann spoke with LA Times national security correspondent, Brian Bennett, 9:07 9:00 Foreign News for more. Take Two: Social Media Accounts: A proposal floated by US Customs and Border Control would ask people to voluntarily tell border agents everything about their social media accounts and screen names. Russell Brandom reporter for The Verge, spoke 9:16 7:00 Foreign News to Libby Denkmann about it. Law & Order/Courts/Polic Take Two: Use of Force: One year ago, the LAPD began training officers to use de-escalation techniques. How are they working 9:23 8:00 e out? Maria Haberfeld, professor of police science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice spoke to A Martinez about it. Take Two: OC Refugee dinner: After 16 hours without food and water, one refugee family will break their Ramadan fast with mostly strangers. They are living in Orange County after years of going through the refugee process to enter the United States. 9:34 4:10 Orange County Nuran Alteir reports. Take Two: Road to Rio: A Martinez speaks with Desiree Linden, who will be running the women's marathon event for the US in 9:38 7:00 Sports this year's Olympics. Take Two: LA's best Hot dog: We here at Take Two were curious to know: what’s are our listeners' favorite LA hot dog? They tweeted and facebooked us with their most adored dogs, and Producers Francine Rios, Lori Galarreta and host Libby Denkmann 9:45 6:10 Arts And Culture hit the town for a Take Two taste test. -

Octodec2017 Copy.Pages

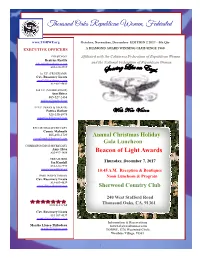

Thousand Oaks Republican Women, Federated www.TORWF.org October, November, December EDITION 2 2017 - 4th Qtr EXECUTIVE OFFICERS A DIAMOND AWARD WINNING CLUB SINCE 1960 PRESIDENT Affiliated with the California Federation of Republican Women Beatrice Restifo [email protected] and the National Federation of Republican Women 805-230-2919 ! 1st V.P. (PROGRAMS) Cav. Rosemary Licata [email protected] 818-889-4839 2nd V.P. (MEMBERSHIP) Ann Shires 805-527-2468 [email protected] 3rd V.P. (WAYS & MEANS) Patrice Barlow With New Vision 925-330-6978 [email protected] RECORDING SECRETARY Connie Malmuth 805-498-2729 Annual Christmas Holiday [email protected] Gala Luncheon CORRESPONDING SECRETARY Anne Hetu 805-497-1404 Beacon of Light Awards TREASURER Isa Kendall Thursday, December 7, 2017 818-640-2975 [email protected] 10:45 A.M. Reception & Boutiques PARLIAMENTARIAN Noon Luncheon & Program Cav. Rosemary Licata 818-889-4839 [email protected] Sherwood Country Club 240 West Stafford Road Thousand Oaks, CA. 91361 NEWSLETTER Cav. Rosemary Licata 818-889-4839 [email protected] Information & Reservations Marsha Llanes-Thibodeau [email protected] [email protected] TORWF, 1276 Westwind Circle Westlake Village, 91361 1 President’s Message Well, we have done it again. At the National Federation of Republican Women, Thousand Oaks Republican Women, Federated received the honored Diamond Achievement Award which is earned by clubs for community programs, political activity, general meetings, etc. for 2016-2017. Thank you to the many members who have participated in our programs and events during this time. You are the ones who have helped us achieve prestigious this honor. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at an African

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at an African American History Month Listening Session February 1, 2017 The President. Hello, everybody. Participants. Good morning, Mr. President. The President. These are a lot of my friends, but you have been so helpful, Darrell. I appreciate that. You have been really, really—and we did well. The election, we—it came out really well. Next time, we'll triple it up or quadruple it, right? Participant. That's right. The President. And we want to get over 51, right? At least 51. Well, this is Black History Month, so this is our little breakfast, our little get together. Hi, Lynne, how are you? Department of Housing and Urban Development Director of Public Liaison Lynne Martine Patton. Hi, how are you, sir? The President. Good, nice to see you. And just a few notes. During this month, we honor the tremendous history of the African Americans throughout our country—throughout the world, if you really think about it, right? And their story is one of unimaginable sacrifice, hard work, and faith in America. I've gotten a real glimpse during the campaign, I'd go around with Ben to a lot of different places that I wasn't so familiar with. They're incredible people. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development–designate Benjamin S. Carson, Sr. Absolutely The President. And I want to thank Ben Carson, who's going to be heading up HUD. And it's a big job, and it's a job that's not only housing, it's mind and spirit, right, Ben? Secretary-designate Carson. -

Media Coverage Print

MCC Presidential Visit (7/7/21): Media Coverage Print President Biden travels to Crystal Lake on Wednesday in first Illinois presidential visit, Chicago Sun- Times, 7/3/21 https://chicago.suntimes.com/politics/2021/7/3/22562494/president-joe-biden-travels-to-crystal-lake- on-wednesday-in-first-illinois-presidential-visit WASHINGTON – President Joe Biden will make his first presidential visit to Illinois on Wednesday when he travels to Crystal Lake — a northwest suburb in McHenry County that former President Donald Trump won in 2020. The White House announced the visit Saturday night. Sources told the Chicago Sun-Times that Biden, unless plans change, will appear at the McHenry County College in Crystal Lake. Biden will be at the community college to promote his American Families Plan — a package of proposals dealing with, among other items, child poverty and making college more affordable. While McHenry County voters preferred Trump, Crystal Lake is represented in Congress by Democratic Reps. Lauren Underwood and Sean Casten and they are expected — along with other Illinois Democrats — to be at the event. In April, First Lady Jill Biden, who teaches at a community college in northern Virginia, made her first visit to Illinois, appearing at Sauk Valley Community College in Dixon. President Biden to visit Crystal Lake on Wednesday, MyStateline.com, 7/4/21 https://www.mystateline.com/news/president-biden-to-visit-crystal-lake-on-wednesday/ CRYSTAL LAKE, Ill. (WTVO) — On Wednesday, July 7th, President Joe Biden is expected to visit Crystal Lake, in McHenry County. President Biden has been on the road, trying to sell voters on the economic benefits of the $973 billion infrastructure package. -

News English 新聞英文

News English Course Materials 新聞英文 課程自編講義 授課老師: 葉姿青 學生姓名: ______________ 學 號: ______________ Table of Contents: 目 錄 1. Course Syllabus・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・p. 3 2. Grading ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・p. 5 3. Introduction to News English・・・・・・・・p. 6 4. News English Structure・・・・・・・・・・・・p. 8 5. Politics: Left and Right・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・p. 10 6. Politics: Conspiracy Theory・・・・・・・・・・・・・p. 14 7. Finance: The Global Recession・・・・・・・・・・・p. 16 8. Surveillance and WikiLeaks・・・・・・・・・・・・・p. 19 9. Terrorism and Terrorist Attack・・・・・・p.27 10. Refugee Crisis・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・p.37 11. Environment・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・p.39 12. Zika Virus・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・p.45 13. Appendix (1): Expression Key・・・・・・・p.53 14. Appendix (2): Exercise Sheets・・・・・・・p.55 15. Appendix (3):Writing Style Guide・・・・p.57 16. Appendix (4): On “Fake News”・・・・p.60 2 1. Course Syllabus Week Date Course Contents 1 2/16 Introduction to course Introduction to News English 2 2/23 Exercise: View 1st MOOCS and online test in class. Introduction to Structure of News Article 3 3/2 Preview: Complete 2nd MOOCS and the 2nd online test before attending the class. Politics: Left and Right 4 3/9 Preview: Complete 3rd MOOCS and online test. Politics: Conspiracy Theory 5 3/16 Preview: Complete 4th MOOCS and online test. Finance: The Global Recession 6 3/23 Preview: Complete 5th MOOCS and online test. 7 3/30 Social Issue: The World of Surveillance and WikiLeaks Feedback on Report 1. Submit 1st journal report (word document, 250-word, 8 4/6 double space) on the platform, and print out a hardcopy. 2. Complete Evaluation Form for peer review. 9 4/13 Midterm Presentation: Give an individual 3-5 minutes PPT presentation based on the topics and related issues 10 4/20 discussed in previous weeks. -

Who's Feeling the Burn?

TPA TEXAS PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION This paper can www.TheAustinVillager.com be recycled Vol. 47 No. 34 Phone: 512-476-0082 Email: [email protected] March 13, 2020 Who’s Feeling The Burn? INSIDE By WILL WEISSERT and LAURIE KELLMAN | Associated Press Award-winning RAPPIN’ journalist receives Tommy Wyatt Prominence Honor. See RICHARD And Then Page 2 There Were Two! When the political Prescott may play season started, there were under exclusive more than twenty franchise tag. Democrats who stepped See COWBOYS up to take on President Page 7 Donald Trump in the next Democratic Presidential candidate former Vice President Joe Biden addresses the media and a presidential election. small group of supporters with his wife Dr. Jill Biden during a primary night event on March 10, These candidates repre- 2020 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Six states - Idaho, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Washington, sented voters from all over and North Dakota held nominating contests today. (Photo by Mark Makela/Getty Images) America. While the president WASHINGTON (AP) — Joe Biden decisively “We need you; we want you, and there’s a did not see any of these won Michigan’s Democratic presidential primary, place in our campaign for each of you. I want to Ex-Presidential candidates serious con- seizing a key battleground state that helped propel thank Bernie Sanders and his supporters for their hopeful seeks to tenders to defeating him in Bernie Sanders’ insurgent candidacy four years ago. tireless energy and their passion,” Biden said. “We improve education. the next election, they all The former vice president’s victory there, as well as share a common goal, and together we’ll beat See BLOOMBERG waged serious campaigns in Missouri, Mississippi and Idaho, dealt a serious Donald Trump.” Page 8 throughout the country.