Disability & Society the Elephant Man (David Lynch, EMI Films, 1980)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Elephant Man STAGE 1

The Elephant Man STAGE 1 Before Reading 5 What . .? She screamed, dropped his food on the floor, and ran out of the room. 6 Why . .? Because people couldn’t look at him in a TALKING ABOUT THE COVER lighthouse. • Why do you think the man is dressed in this way? Possible answers: (Is he dead, a ghost, ill, ugly, not human?) POLICE: Now, Mr Merrick. Where do you live, sir? • Is this going to be a ghost story, a horror story, a MERRICK: I don’t know. I don’t have a home. (I don’t sad story, a happy story? live anywhere.) • What do you think an ‘Elephant Man’ is? POLICE: Do you have any money, sir? (Someone who looks after elephants, knows a lot MERRICK: No, I don’t. about elephants, looks like an elephant) POLICE: Why not? What happened to your money? MERRICK: I had £50 in Belgium, but a man called Silcock took it away from me. BEFORE READING ACTIVITIES (PAGE 44) POLICE: You can’t stay in prison. Where do you want ACTIVITIES ANSWERS to go now? ACTIVITY 1 BEFORE READING MERRICK:To the London Hospital. 1 Yes 2 No 3 No 4 Yes 5 No 6 Yes 7 Yes POLICE: Why? Do you know somebody there? ERRICK ACTIVITY 2 BEFORE READING M : Yes. His name is Dr Treves. Look – here is Open answers. Encourage students to speculate and to his card. make guesses, but do not tell them the answers. They POLICE: Ah, I see. All right, sir. Let’s go and see him will find out as they read that the ‘yes’ answers are now. -

The Historical Articulation of the Disabled Body in the Archive

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Spring 2019 Speaking for the Grotesques: The Historical Articulation of the Disabled Body in the Archive Violet Marie Strawderman Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Disability Studies Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Strawderman, Violet M.. "Speaking for the Grotesques: The Historical Articulation of the Disabled Body in the Archive" (2019). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/ 3qzd-0r71 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/80 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPEAKING FOR THE GROTESQUES: THE HISTORICAL ARTICULATION OF THE DISABLED BODY IN THE ARCHIVE by Violet Marie Strawderman B.A. May 2016, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS ENGLISH OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2019 Approved by: Drew Lopenzina (Director) Ruth Osorio (Member) Elizabeth J. Vincelette (Member) ABSTRACT SPEAKING FOR THE GROTESQUES: THE HISTORICAL ARTICULATION OF THE DISABLED BODY IN THE ARCHIVE Violet Marie Strawderman Old Dominion University, 2019 Director: Dr. Drew Lopenzina This project examines the ways in which the disabled body is constructed and produced in larger society, via the creation of and interaction with (and through) the archive. -

Introduction Sir Frederick Treves (1853-1923) Joseph Carey Merrick

in 1923. in even through ill health until her death in 1919. in death her until health ill through even reminiscences of Joseph published shortly before his death death his before shortly published Joseph of reminiscences with improved accommodation. She remained as Matron Matron as remained She accommodation. improved with science. in 1908 and wrote popular travel literature as well as his his as well as literature travel popular wrote and 1908 in in 1895, and ensured that the nursing staff were provided provided were staff nursing the that ensured and 1895, in medical of benefit the for Act Anatomy the of terms the operated on Edward VII before his coronation. He retired retired He coronation. his before VII Edward on operated Nursing Institution in 1885, the Preliminary Training School School Training Preliminary the 1885, in Institution Nursing under College Medical the by preserved was skeleton His in the Boer War with his own surgical unit and famously famously and unit surgical own his with War Boer the in the examination. Eva Lückes established the Private Private the established Lückes Eva examination. the 1890. in death his until there resident a remained and www.qmul.ac.uk/publicengagement pioneered the operation to remove the appendix. He served served He appendix. the remove to operation the pioneered to complete two years of training with another year following following year another with training of years two complete to hospital the by in taken was He savings. his of robbed by the Centre for Public Engagement. Engagement. Public for Centre the by published many important works on surgery and anatomy anatomy and surgery on works important many published nursing at the hospital. -

English Language and Literature Modules

English Language and Literature Modules Autumn semester: EGH6023 Reconsidering the Renaissance (30 credits) This module is designed both to explore the concept of 'the Renaissance' and to interrogate it. It examines the ways in which late medieval and early modern writers approached the Renaissance's defining project of cultural rebirth, including translation of and allusion to classical literature, and it encourages students to identify (and question) processes of periodisation and canon-formation in pre-modern texts and modern criticism alike. It also introduces students to the medieval and Renaissance discourses and practices within which these developments took place, such as manuscript circulation, printing, letter-writing, and changing notions of authorship. LIT631 Post-War British Drama, Film & TV (30 credits) This module provides the opportunity for parallel study of the British drama, cinema and television of the post- war period. This era saw the emergence of influential styles, prominent figures and landmark texts in all three artistic forms: e.g. the plays of John Osbourne (Look Back in Anger), television drama (Cathy Come Home) and key British films, such as Ealing comedies (The Man in the White Suit), retrospective war films (The Cruel Sea) and social problem films (Sapphire). The module will explore the evolving post-war cultural landscape to contextualise and critically appraise examples from these interrelated literary, performative and representational media. LIT635 Confession (30 credits) "Western man has become a confessing animal," or so Michel Foucault contended. This module interrogates confessional acts in literature and culture, beginning with St Augustine's Confessions (often considered the first autobiography in the Western tradition) and focusing in particular upon eighteenth- and nineteenth-century forms. -

Work Placement Modules

WORK PLACEMENT MODULES EGH6025 Language and Literature in the Work Place—Convened by Dr Amber Regis 15 credits (Spring Semester) This module will give you the opportunity to work with an external organisation, applying your research and communication skills to a specific project. You will undertake 100 hours of work with an external partner on an agreed project. At the end of the project you complete a log and record of your activities, and write a reflective essay. NB: You will be allocated to your placement early in Semester 1 (Autumn), but your placement will be worked and assessed in Semester 2 (Spring). The module will be of interest to students who plan to continue to a PhD as you will develop skills of direct relevance to your doctoral research (e.g. working with archives, museums, oral histories, with social media). It will also give you experience of engaging members of the public with academic research. It may also be of interest to students who do not plan to continue to a PhD as it will enable you to undertake valuable work experience and develop your CV. Recent projects have included: Research and web content provider for the Sheffield Arts and Well-Being Network. Social media researcher for Sheffield Archives. Crowd-funding and publishing Route 57. Project assistant at Grimm & Co. a local Children’s literary charity. Project assistant on ‘Gothic Tourism’ with Haddon Hall and Whitby Museum. Charity event organisation with the Women’s Institute. Cataloguing the Keith Dewhurst Collection in the University Library’s Special Collections. Working on the ‘Sheffield Musical Map’ project with Sensoria Festival. -

Service Review

Editorial Standards Findings Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee January 2013 issued March 2013 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers Editorial Standards Findings/Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered Contentsby the Editorial Standards Committee Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee 1 Summaries of findings 3 Appeal Findings 7 BBC News, BBC One, Sunday 27 May 2012, 5.50pm 7 Have I Got News For You?, BBC One, 1 June 2012 14 What The Papers Say, BBC Radio 4, 29 July 2012 20 BBC Online Olympic Country Profiles 34 Rejected Appeals 44 Who Dares Wins, BBC One, 11 February 2012 44 Countryfile, BBC One, 6 May 2012 47 Eurovision Song Contest Semi-Finals, BBC Three, 8pm 22 and 24 May 2012 51 “Treasury messing with UK clean energy policy, say MPs”, BBC Online, 23 July 2012 55 Is Football Racist?, BBC Three, 16 July 2012 60 The World at One, BBC Radio 4, 9 May 2012 65 Decision at Stage 1 to close complaint about BBC coverage of climate change 68 January 2013 issued March 2013 Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee The Editorial Standards Committee (ESC) is responsible for assisting the Trust in securing editorial standards. It has a number of responsibilities, set out in its Terms of Reference at http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbctrust/assets/files/pdf/about/how_we_operate/committees/2011/ esc_tor.pdf. The Committee comprises five Trustees: Alison Hastings (Chairman), David Liddiment, Richard Ayre, Sonita Alleyne and Bill Matthews. It is advised and supported by the Trust Unit. -

Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking

Nineteenth-Century Contexts An Interdisciplinary Journal ISSN: 0890-5495 (Print) 1477-2663 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gncc20 Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking Sharrona Pearl To cite this article: Sharrona Pearl (2016) Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking, Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 38:2, 93-106, DOI: 10.1080/08905495.2016.1135366 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2016.1135366 Published online: 12 Feb 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 135 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gncc20 Download by: [University of Pennsylvania] Date: 20 October 2016, At: 06:50 NINETEENTH-CENTURY CONTEXTS, 2016 VOL. 38, NO. 2, 93–106 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2016.1135366 Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking Sharrona Pearl The Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA Introduction Let us think together about pleasure. Is everything that we enjoy pleasurable, and can there be plea- sure in that which we do not enjoy? And, poignantly, when and why do we feel the need to apologize for pleasure? Pleasure has been coupled with a variety of visual practices and experiences, and, at its extremes, has been tarred with the judgmental brush of fetish.1 There are some things, it seems, that are not okay to look at. Or, more specifically, there are some things that are not okay to enjoy looking at. -

Six Monthly Media Update PDF 90 KB

Committee(s) Dated: Public Relations and Economic Development Sub 17/06/2019 Committee Subject: Public Six-Month Media Update Report of: For Information Bob Roberts, Director of Communications Report author: Aisha Musad, Media Office Assistant Summary This report summarises the media output over the past six-months from the City of London Corporation Media Team. It shows there have been over 550 articles relating to the City of London Corporation in national and local newspapers with the advertising value equivalent of £6,121,591. Recommendation Members are asked: to note the contents of this report. Main Report Background 1. The Weekly Media Summary has continued to measure and record the main print and digital media output of the Media Team. 2. This report collates and summarises the finding of the Weekly Media Summary from mid-December 2018 to mid-June 2019. Print 3. There have been over 550 articles relating to the City of London Corporation in national and local newspapers. 4. Advertising Value Equivalent (equivalent if we paid for coverage) of £6,121,591 (this excludes radio and broadcasting coverage). 5. Additionally, there have been at least 447 articles in international media which are not collated by the cutting agency and which are not included in the AVE figure. Digital 6. The corporate Twitter feed now has 44,138 followers. 7. One of our top tweets with a reach of 3. 3m people was @cityoflondon supporting @LivingWageUK encouraging City financial and professional services firms to pay the London Living Wage. 8. Our corporate Facebook pages have 40,623 followers and generating 45,478 engagements. -

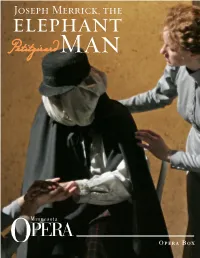

Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man Opera Box Lesson Plan Unit Overview with Related Academic Standards

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis . .22 Laurent Petitgirard – a biography ............................25 Background Notes . .27 History of Opera ........................................31 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .42 The Standard Repertory ...................................46 Elements of Opera .......................................47 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................51 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................57 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .60 Acknowledgements . .62 GIACOMO PUCCINI NOVEMBER 5 – 13, 2005 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART MARCH 4 – 12, 2006 mnopera.org SAVERIO MERCADANTE APRIL 8 – 15, 2006 LAURENT PETITGIRARD MAY 13 – 21, 2006 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. As this project is new, your feedback is imperative. Comments and ideas from you – the educators who actually use it – will help shape the content for future boxes. In addition, you are encouraged to include any original lesson plans. -

KANTIAN THEMES in the ELEPHANT MAN (Forthcoming in Film and Philosophy)

KANTIAN THEMES IN THE ELEPHANT MAN (forthcoming in Film and Philosophy) Finding films that embody at least some elements of the moral philosophy of Immanuel Kant is not too difficult. Others have written on the ways in which films as diverse as High Noon and Hotel Rwanda can be used in ethics classes to explain various aspects of Kant’s ethics.1 In what follows, I will try to make the case that David Lynch's The Elephant Man is one of the best films to use for both introducing and sympathetically understanding Kant’s moral philosophy. The film does not merely focus on duty, or the tensions that can arise between consequentialist and deontological approaches to ethical decision making. It also helps us understand Kant’s views on moral worth, friendship, and the value of rationality and personhood. In addition, it contains aspects which can help us critically examine the limits and overall plausibility of a Kantian ethical framework. Finally, it is a terrific film that most students have not yet had the opportunity to see, so introducing them to it offers the possibility of both aesthetic and moral enrichment.2 The Elephant Man is the story of a “poor wretch” named John Merrick, who is afflicted with a horribly disfiguring disease. His disfiguration is so severe that Merrick is relegated to appearing in a freak show as the “Elephant Man.” Set in the Victorian era, the story follows Merrick’s journey from abused side-show attraction to pampered international celebrity. This transformation occurs primarily through the efforts of Doctor Frederick Treves, who rescues Merrick from an exploitative barker and provides him with a more humane home within his hospital. -

David Lynch: Elephant Man (1980, 124 Min.) Online Versions of the Goldenrod Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Links

October 30, 2018 (XXXVII:10) David Lynch: Elephant Man (1980, 124 min.) Online versions of The Goldenrod Handouts have color images & hot links: http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html DIRECTED BY David Lynch WRITING screenplay by Christopher De Vore, Eric Bergren, and David Lynch; Frederick Treves (book) (as Sir Frederick Treves), Ashley Montagu (in part on the book "The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity") PRODUCED BY Stuart Cornfeld (executive producer), Jonathan Sanger (producer), and Mel Brooks (executive producer, uncredited) MUSIC John Morris CINEMATOGRAPHY Freddie Francis (director of photography) FILM EDITING Anne V. Coates PRODUCTION DESIGN Stuart Craig ART DIRECTION Robert Cartwright SET DECORATION Hugh Scaife COSTUME DESIGN Patricia Norris MAKEUP DEPARTMENT hairdressers: Paula Gillespie and Stephanie Kaye; makeup artists: Beryl Lerman and Michael Morris; makeup application: 'Elephant Man' / makeup supervisor: Wally Schneiderman; makeup creator: 'Elephant Man' / makeup designer: 'Elephant Man': Christopher Tucker The film received eight nominations at the 1981Academy Awards: Best Picture: Jonathan Sanger; Best Actor in a Leading Role: John Hurt; Best Director: David Lynch; Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium: Christopher De Vore, Eric Bergren, David Lynch; Best Art Direction-Set Decoration: Stuart Craig, Robert Cartwright, Hugh Scaife; Best Costume Design: Patricia Norris; Best Film Editing: Anne V. Coates; Best Music, Original Score: John Morris. CAST Anthony Hopkins...Frederick Treves John Hurt...John Merrick Alfie Curtis...Milkman Anne Bancroft...Mrs. Kendal Bernadette Milnes...1st Fighting Woman John Gielgud...Carr Gomm Brenda Kempner...2nd Fighting Woman Wendy Hiller...Mothershead Carol Harrison ...Tart (as Carole Harrison) Freddie Jones ...Bytes Hugh Manning...Broadneck Michael Elphick...Night Porter Dennis Burgess...1st Committee Man Hannah Gordon...Mrs. -

Agosto HOMEM ELEFANTE-Cópia.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! A!Heterotopia!do!Corpo:!do!Homem!Elefante!ao!Freak!Neovitoriano! ! ! Catarina!Luís!de!Carvalho!Moura! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dissertação!de!Mestrado!em!Línguas,!Literaturas!e!! Culturas!! EspeCialização!em!Estudos!Ingl! esas!e!NorteLAmeriCanas! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Agosto,!2016! Versão!corrigida!após!defesa!pública.! Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas, Especialização em Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos, realizada sob a orientação científica da Prof.ª Doutora Iolanda Ramos. Versão corrigida após defesa pública. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AGRADECIMENTOS ! ! ! ! À minha orientadora e professora, Iolanda Ramos, pelo entusiasmo e pela perseguição de ideias novas e originais. Aos meus amigos, que sempre me dão ideias. Aos meus pais e para eles. Ao Nuno, como sempre. 2 " A Heterotopia do Corpo: do Homem Elefante ao Freak Neovitoriano Catarina Luís de Carvalho Moura RESUMO Joseph Merrick (1862-1890), o Homem Elefante, é mitificado pelo médico Frederick Treves nas suas memórias The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923). Enquando freak, Joseph Merrick ilustra bem a relação entre corpos normativos e corpos disruptivos, assim como a fronteira ténue entre a esfera científica e a esfera popular. Para compreender o freak show vitoriano é essencial ter em conta que o conceito de normal é uma construção forjada pelo século XIX e define o que é humano ou animal, civilizado ou primitivo, belo ou grotesco. A definição e prescrição do normal acontece no acto de observação dos corpos extraordinários, o que continua a ocorrer actualmente, quer em obras neovitorianas, quer na televisão do século XXI. A definição do Eu pelo Outro, sendo o Outro radicalmente diferente e simultaneamente igual, constitui a ideia de heterotopia, descrita por Michel Foucault, e neste caso particular, aplicada ao corpo.