The Rāgas in Its Winged Form, Its Ideal Performance And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

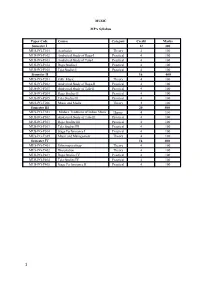

Music & Dance Session 2020-21

1 FACULTY OF PERFORMING & VISUAL ARTS SYLLABUS Of MUSIC VOCAL For B.A. (Semester- I to VI ) (UnderContinuous Evaluation System) (12+3 System of Education) Session: 2020-21 The Heritage Institution KANYA MAHA VIDYALAYA JALANDHAR (Autonomous) B.A. (Semester- I) 1 2 Scheme of Studies and Examination Music Vocal SemesterI Course Marks Examinati Course Name Program Name Course Code Type Ext. on time Total CA L P (in Hours) Music Vocal B.A BARM-1366 E 100 40 40 20 3 B.A. Semester-I (Session 2020-21) Music Vocal Course Code: BARM-1366 Theory & Practical Course Outcome Upon successful completion of this course student will be able to know the basic concepts of music , which are - CO1 . Proficiency in playing Alankar , which are helpful in further learning of ragas. CO2. To know the lives of great musician who are torch bearers of Indian classical music. CO3. To Know about Tanpura, its structure , its sound Producing system and tuning of the instrument. B.A. Semester-I (Session 2020-21) Music Vocal Course Code: BARM-1366 2 3 Theory Total Marks-100 Time-3Hours Theory: 40 Pr: 40 CA: 20 Instructions given to the examiners are as follows: The paper setter will set Eight questions of equal marks . Two in each of the four Sections (A- D). Questions of Sections A-D should be set from Units I-IV of the syllabus respectively. Questions may be subdivided into parts (not exceeding four). Candidates are required to attempt five questions, selecting at least one question from each section. The fifth question may be attempted from any Section. -

A Novel Hybrid Approach for Retrieval of the Music Information

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 12, Number 24 (2017) pp. 15011-15017 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com A Novel Hybrid Approach for Retrieval of the Music Information Varsha N. Degaonkar Research Scholar, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication, JSPM’s Rajarshi Shahu College of Engineering, Pune, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Maharashtra, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0002-7048-1626 Anju V. Kulkarni Professor, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication, Dr. D. Y. Patil Institute of Technology, Pimpri, Pune, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Maharashtra, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0002-3160-0450 Abstract like automatic music annotation, music analysis, music synthesis, etc. The performance of existing search engines for retrieval of images is facing challenges resulting in inappropriate noisy Most of the existing human computation systems operate data rather than accurate information searched for. The reason without any machine contribution. With the domain for this being data retrieval methodology is mostly based on knowledge, human computation can give best results if information in text form input by the user. In certain areas, machines are taken in a loop. In recent years, use of smart human computation can give better results than machines. In mobile devices is increased; there is a huge amount of the proposed work, two approaches are presented. In the first multimedia data generated and uploaded to the web every day. approach, Unassisted and Assisted Crowd Sourcing This data, such as music, field sounds, broadcast news, and techniques are implemented to extract attributes for the television shows, contain sounds from a wide variety of classical music, by involving users (players) in the activity. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Master of Performing Arts (Vocal & Instrumental)

MASTER OF PERFORMING ARTS (VOCAL & INSTRUMENTAL) I SEMESTER Course - 101 (Applied Theory) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To critically appreciate a music concert. 2. To understand and compare the ragas and talas prescribed for practical’s. 3. To write compositions in the prescribed notation system. 4. To introduce students to staff notation. Course Content:- I. Theoretical study of Ragas and Talas prescribed for practical and their comparative study wherever possible. II. Reading and writing of Notations of compositions Alap, Taan etc. in the Ragas and Talas with prescribed Laykraries. III. Elementary Knowledge of Staff Notation. IV. Critical appreciation of Music concert. Bibliographies:- a. Dr. Bahulkar, S. Kalashastra Visharad (Vol. 1 - 4 ). Mumbai:: Sanskar Prakashan. b. Dr. Sharma, M. Music India. A. B. H. Publishing Hoouse. c. Dr. Vasant. Sangeet Visharad. Hatras:: Sangeet Karyalaya. d. Rajopadhyay, V. Sangeet Shastra. Akhil Bhartiya Gandharva Vidhyalaya e. Rathod, B. Thumri. Jaipur:: University Book House Pvt. Ltd. f. Shivpuji, G. Lay Shastra. Bhopal: Madhya Pradesh Hindi Granth. Course - 102 (General Theory) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To study Aesthetics in Music. 2. To appreciate the aesthetic aspects of different forms of music. Course Content:- I. Definition of Aesthetics and its Application in Music. II. Aesthetical principles of Different Haran’s. III. Aesthetical aspects of different forms of Music. a. Dhrupad, Dhamar, Khayal, Thumri, Tappa etc. IV. Merits and demerits of vocalist. Bibliographies:- a. Bosanquet, B. (2001). The concept of Aesthetics. New Delhi: Sethi Publishing Company. b. Dr. Bahulkar, S. Kalashastra Visharad (Vol. -

Hindustani Classic Music

HINDUSTANI CLASSIC MUSIC: Junior Grade or Prathamik : Syllabus : No theory exam in this grade Swarajnana Talajnana essential Ragajnana Practicals: 1. Beginning of swarabyasa - in three layas 2. 2 Swaramalikas 5 Lakshnageete Chotakyal Alap - 4 ragas Than - 4 Drupad - should be practiced 3. Bhajan - Vachana - Dasapadas 4. Theental, Dadara, Ektal (Dhruth), Chontal, Juptal, Kheruva Talu - Sam-Pet-Husi-Matras - should practice Tekav. 5. Swarajnana 6. Knowledge of the words - nada, shruthi, Aroha, Avaroha, Vadi - Samvedi, Komal - Theevra - Shuddha - Sasthak - Ganasamay - Thaat - Varjya. 7. Swaralipi - should be learnt. Senior Grade: (Madhyamik) Syllabus : Theory: 1. Paribhashika words 2. Sound & place of emergence of sound 3. The practice of different ragas out of “thaat” - based on Pandith Venkatamukhi Mela System 4. To practice ragalaskhanas of different ragas 5. Different Talas - 9 (Trital, Dadra, Jup, Kherva, Chantal, Tilawad, Roopak, Damar, Deepchandi) explanation of talas with Tekas. 6. Chotakhyal, Badakhyal, Bhajan, Tumari, Geethprakaras - Lakshanas. 7. Life history of Jayadev, Sarangdev, Surdas, Purandaradas, Tansen, Akkamahadevi, Sadarang, Kabeer, Meera, Haridas. 8. Knowledge of musical instrument Practicals: 1. Among 20 ragas - Chotakhyal in each 2. Badakhyal - for 10 ragas (Bhoopali, Yamani, Bheempalas, Bageshree, Malkonnse, Alhaiah Bilawal, Bahar, Kedar, Poorvi, Shankara. 3. Learn to sing one drupad in Tay, Dugun & Changun - one Damargeete. VIDHWAN PROFICIENCY Syllabus: Theory 1. Paribhashika Shabdas. 2. 7 types of Talas - their parts (angas) 3. Tabala bol - Tala Jnana, Vilambitha Ektal, Jumra, Adachontal, Savari, Panjabi, Tappa. 4. Raga lakshanas of Bhairav, Shuddha Sarang, Peelu, Multhani, Sindura, Adanna, Jogiya, Hamsadhwani, Gandamalhara, Ragashree, Darbari, Kannada, Basanthi, Ahirbhairav, Todi etc., Alap, Swaravisthara, Sama Prakruthi, Ragas criticism, Gana samay - should be known. -

Analyzing the Melodic Structure of a Raga-Based Song

Georgian Electronic Scientific Journal: Musicology and Cultural Science 2009 | No.2(4) A Statistical Analysis Of A Raga-Based Song Soubhik Chakraborty1*, Ripunjai Kumar Shukla2, Kolla Krishnapriya3, Loveleen4, Shivee Chauhan5, Mona Kumari6, Sandeep Singh Solanki7 1, 2Department of Applied Mathematics, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India 3-7Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India * email: [email protected] Abstract The origins of Indian classical music lie in the cultural and spiritual values of India and go back to the Vedic Age. The art of music was, and still is, regarded as both holy and heavenly giving not only aesthetic pleasure but also inducing a joyful religious discipline. Emotion and devotion are the essential characteristics of Indian music from the aesthetic side. From the technical perspective, we talk about melody and rhythm. A raga, the nucleus of Indian classical music, may be defined as a melodic structure with fixed notes and a set of rules characterizing a certain mood conveyed by performance.. The strength of raga-based songs, although they generally do not quite maintain the raga correctly, in promoting Indian classical music among laymen cannot be thrown away. The present paper analyzes an old and popular playback song based on the raga Bhairavi using a statistical approach, thereby extending our previous work from pure classical music to a semi-classical paradigm. The analysis consists of forming melody groups of notes and measuring the significance of these groups and segments, analysis of lengths of melody groups, comparing melody groups over similarity etc. Finally, the paper raises the question “What % of a raga is contained in a song?” as an open research problem demanding an in-depth statistical investigation. -

The Concept of Tala 1N Semi-Classical Music

The Concept of Tala 1n Semi-Classical Music Peter Manuel Writers on Indian music have generally had less difficulty defining tala than raga, which remains a somewhat abstract, intangible entity. Nevertheless, an examination of the concept of tala in Hindustani semi-classical music reveals that, in many cases, tala itself may be a more elusive and abstract construct than is commonly acknowledged, and, in particular, that just as a raga cannot be adequately characterized by a mere schematic of its ascending and descending scales, similarly, the number of matra-s in a tala may be a secondary or even irrelevant feature in the identification of a tala. The treatment of tala in thumri parallels that of raga in thumn; sharing thumri's characteristic folk affinities, regional variety, stress on sentimental expression rather than theoretical complexity, and a distinctively loose and free approach to theoretical structures. The liberal use of alternate notes and the casual approach to raga distinctions in thumri find parallels in the loose and inconsistent nomenclature of light-classical tala-s and the tendency to identify them not by their theoretical matra-count, but instead by less formal criteria like stress patterns. Just as most thumri raga-s have close affinities with and, in many cases, ongms in the diatonic folk modes of North India, so also the tala-s of thumri (viz ., Deepchandi-in its fourteen- and sixteen-beat varieties-Kaharva, Dadra, and Sitarkhani) appear to have derived from folk meters. Again, like the flexible, free thumri raga-s, the folk meters adopted in semi-classical music acquired some, but not all, of the theoretical and structural characteristics of their classical counterparts. -

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute Regulations And Programme of Studies B. A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) (Review) - 1 - UNIVERSITY OF MAURITIUS MAHATMA GANDHI INSTITUTE PART I General Regulations for B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 1. Programme title: B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 2. Objectives To equip the student with further knowledge and skills in Vocal Hindustani Music and proficiency in the teaching of the subject. 3. General Entry Requirements In accordance with the University General Entry Requirements for admission to undergraduate degree programmes. 4. Programme Requirement A post A-Level MGI Diploma in Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) or an alternative qualification acceptable to the University of Mauritius. 5. Programme Duration Normal Maximum Degree (P/T): 2 years 4 years (4 semesters) (8 semesters) 6. Credit System 6.1 Introduction 6.1.1 The B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) programme is built up on a 3- year part time Diploma, which accounts for 60 credits. 6.1.2 The Programme is structured on the credit system and is run on a semester basis. 6.1.3 A semester is of a duration of 15 weeks (excluding examination period). - 2 - 6.1.4 A credit is a unit of measure, and the Programme is based on the following guidelines: 15 hours of lectures and / or tutorials: 1 credit 6.2 Programme Structure The B.A Programme is made up of a number of modules carrying 3 credits each, except the Dissertation which carries 9 credits. 6.3 Minimum Credits Required for the Award of the Degree: 6.3.1 The MGI Diploma already accounts for 60 credits. -

Performing Arts (91 – 95)

PERFORMING ARTS (91 – 95) One of the following five syllabuses may be offered: Western Music (93) Hindustani Music (91) Indian Dance (94) Carnatic Music (92) Drama (95) HINDUSTANI MUSIC (91) CLASS X The syllabus is divided into three sections: PRACTICAL Section A - Vocal Music 1. Bhairav, Bhopaali and Malkauns - Singing of Section B - Instrumental Music Chotakhayal song in any one raga, as mentioned above (with alaaps and taans). Lakshangeet and Section C - Tabla. Swarmalika in the other two ragas. PART 1: THEORY – 100 Marks 2. Padhant (Reciting)-Thekas of the following new taals - Rupak, Jhaptaal and Deepchandi in Dugun SECTION A: HINDUSTANI VOCAL MUSIC and Chaugun, showing Tali, Khali and Matras on 1. (a) Non-detail terms: Sound (Dhwani), Meend, hands. Kan (Sparsha swar), Gamak, Tigun, Thumri, 3. Identification of ragas - Bhairav, Bhoopali and Poorvang, Uttarang, Poorva Raga and Uttar Malkauns. Raga. SECTION B (b) Detailed topics: Nad, three qualities of Nad (volume, pitch, timbre); Shruti and placement HINDUSTANI INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC of 12 swaras; Dhrupad and Dhamar. (EXCLUDING TABLA) 2. Description of the three ragas - Bhairav, Bhoopali THEORY and Malkauns, their Thaat, Jati, Vadi-Samvadi, Swaras (Varjit and Vikrit), Aroha-Avaroha, Pakad, 1. (a) Non-detail terms: Sound (Dhwani); Kan; time of raga and similar raga. Meend, Zamzama; Gamak; Baj; Jhala; Tigun. (b) Detailed topics: Nad; three qualities of Nad 3. Writing in the Taal notation, the three Taals - Rupak, Jhaptaal and Deepchandi (Chanchar), their (volume, pitch, timbre); Shruti and placement Dugun, Tigun and Chaugun. of 12 swaras; Maseetkhani and Razakhani 4. Knowledge of musical notation system of Pt. V.N. -

Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men

Volume 64, Issue 1, 2020 Journal of Scientific Research Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men Samarpita Chatterjee (Mukherjee) 1, and Roan Mukherjee2* 1 Department of Hindustani Classical Music (Vocal), Sangit-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati (A Central University), Santiniketan, Birbhum-731235,West Bengal, India 2 Department of Human Physiology, Hazaribag College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Demotand, Hazaribag 825301, Jharkhand, India. [email protected] Abstract Several studies have indicated that music therapy may affect I. INTRODUCTION cardiovascular health; in particular, it may bring positive changes Music may be regarded as the projection of ideas as well as in blood pressure levels and heart rate, thereby improving the emotions through significant sounds produced by an instrument, overall quality of life. Hence, to regulate blood pressure, music voices, or both by taking into consideration different elements of therapy may be regarded as a significant complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The respiratory rate, if maintained melody, rhythm, and harmony. Music plays an important role in within the normal range, may promote good cardiac health. The everyone’s life. Music has the power to make one experience aim of the present study was to evaluate the changes in blood harmony, emotional ecstasy, spiritual uplifting, positive pressure, pulse rate and respiratory rate in healthy and disease-free behavioral changes, and absolute tranquility. The annoyance in males (age 50-60 years), at the completion of 30 days of music life may increase in lack of melody and harmony.