51 Mental Factors – a Brief Introduction –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Saṃskāra Section of Vasubandhu's Pañcaskandhaka with Reference to Its Commentary by Sthiramati

A Study of the Saṃskāra Section of Vasubandhu's Pañcaskandhaka with Reference to Its Commentary by Sthiramati Jowita KRAMER 1. Introduction In his treatise "On the Five Constituents of the Person" (Pañcaskandhaka) Vasubandhu succeeded in presenting a brief but very comprehensive and clear outline of the concept of the five skandhas as understood from the viewpoint of the Yogācāra tradition. When investigating the doctrinal development of the five skandha theory and of other related concepts taught in the Pañcaskandhaka, works like the Yogācārabhūmi, the Abhidharmasamuccaya, and the Abhidharmakośa- bhāṣya are of great importance. The relevance of the first two texts results from their close association with the Pañcaskandhaka in terms of tradition. The significance of the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya is due to the assumption of an identical author of this text and the Pañcaskandhaka.1 The comparison of the latter with the other texts leads to a highly inconsistent picture of the relations between the works. It is therefore difficult to determine the developmental processes of the teachings presented in the texts under consideration and to give a concluding answer to the question whether the same person composed the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya and the Pañcaskandhaka. What makes the identification of the interdependence between the texts even more problematic is our limited knowledge of the methods the Indian authors and commentators applied when they composed their works. It was obviously very common to make use of whole sentences or even passages from older texts without marking them as quotations. If we assume the silent copying of older material as the usual method of Indian authors, then the question arises why in some cases the wording they apply is not identical but replaced by synonyms or completely different statements. -

Thrangu Rinpoche II.Pdf

Shenpen Ösel The Clear Light of the Buddha’s Teachings Which Benefits All Beings Volume 4, Number 2 September 2000 Aspiration for the World Over the expanse of the treasured earth in this wide world, May benefit for beings appear like infinite moons’ reflections, Whose refreshing presence brings lasting welfare and happiness To open a lovely array of night-blooming lilies, signs of peace and joy. —The Seventeenth Karmapa, Urgyen Trinley Dorje Shenpen Ösel The Clear Light of the Buddha’s Teachings Which Benefits All Beings Volume 4 Number 2 Contents This issue of Shenpen Ösel is primarily devoted to a series of teachings on the Medicine Buddha Sutra given by the Very Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche in the Cascade Mountains in Washington state in June of 1999. Copyright © 2000 Khenchen Thangu Rinpoche. 3 Introduction 4 A Joyful Aspiration: Sweet Melody for Fortunate Ones By the Seventeenth Karmapa, Urgyen Trinley Dorje 5 A Song By the Sixteenth Karmapa, Rangjung Rigpe Dorje 7 The Medicine Buddha Sutra 7 Twelve Extraordinary Aspirations for the Benefit of Sentient Beings 14 The Buddha Shakyamuni Taught This Sutra to Inspire Us to Practice 23 Mudras, or Ritual Gestures, Help to Clarify the Visualization 33 The Benefits of Hearing and Recollecting the Medicine Buddha’s Name 39 Regular Supplication of the Medicine Buddha Brings Protection 48 The Correct View Regarding Both Deities and Maras 59 Somehow Our Buddha Nature Has Been Awakened, and We Are Very Fortunate Indeed 62 The Twelve Great Aspirations of the Medicine Buddha 65 Without Concentration There Is No Spiritual Progress By Lama Tashi Namgyal 69 The Sky-Dragon’s Profound Roar By Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche Staff Editorial policy Editor Shenpen Ösel is a tri-annual publication of Kagyu Lama Tashi Namgyal Shenpen Ösel Chöling (KSOC), a center for the study and practice of Tibetan vajrayana Buddhism Copy editors, Transcribers, located in Seattle, Washington. -

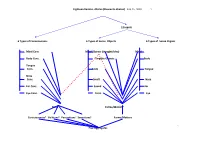

18 Phases Or Realms

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

Chapter-N Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction

44 Chapter-n Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction In the first chapter, Citta (Consciousness) has been introduced. In this chapter, Cetasika (Mental factors) which means depending on citta will be discussed in detail with reference to the Abhidhamma pitaka by dividing topics and subtopics related to the present chapter. In the eighty-nine types of consciousness, enumerated in the first chapter, fifty-two mental factors arise in varying degree.There are seven concomitants common to every consciousness. There are six others that may or may not arise in each and every consciousness. They are termed Pakinnakas or Ethically variable factors. All these thirteen are designated Annasamanas, a rather peculiar technical term. Anna means other, samana means common. Sobhanas (Good), when compared with Asobhanas (Evil), are called Aiina (other) 'being of the opposite category'. Thus the Asobhanas are in contradistinction to Sobhanas. These thirteen become moral or immoral according to the types of consciousness in which they occur. 45 The fourteen concomitants are invariably found in every type of immoral consciousness. The nineteen are common to all type of moral consciousness. The six are moral concomitants which occur as occasion arises. Therefore these fifty-two (7+6+14+19+6=52) are found in all the types of consciousness in different proportions. In this chapter all the 52- mental factors are enumerated and classified. Every type of consciousness is microscopically analysed, and the accompanying psychic factors are given in details. The types of consciousness in which each mental factor occurs, is also described. 2.1. Definition of Cetasika Cetasika=cetas+ika When citta arises, it arises with mental factors that depend on it. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 Kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas The Mind Only school evolved as a response to the possible nihilistic interpretation of the Madhyamaka school. The view “everything is mind” is conducive to the deep practice of meditational yogas. The “Tathagatagarbha”, the ‘Buddha Nature’ was derived from the experience of the Dharmakaya. Tathagata, the ‘Thus Come one’ is a name for a Buddha ( as is Sugata, the ‘Well gone One’ ). Garbha means ‘embryo’ and ‘womb’, the container and the contained, the seed of awakening . This potential to attain Buddhahood is said to be inherent in every sentient being but very often occluded by kleshas, ( ‘negative emotions’) and by cognitive obscurations, by wrong thinking. These defilements are adventitious, and can be removed by practicing Buddhist yogas and trainings in wisdom. Then the ‘Sun of the Dharma’ breaks through the clouds of obscurations, and shines out to all sentient beings, for great benefit to self and others. The 3 svabhavas, 3 kinds of essential nature, are unique to the mind only theory. They divide what is usually called ‘conventional truth’ into two: “Parakalpita” and “Paratantra”. Parakalpita refers to those phenomena of thinking or perception that have no basis in fact, like the water shimmering in a mirage. Usual examples are the horns of a rabbit and the fur of a turtle. Paratantra refers to those phenomena that come about due to cause and effect. They have a conventional actuality, but ultimately have no separate reality: they are empty. Everything is interconnected. -

Cūḷa Sīha,Nāda Sutta

M 1.1.1 Majjhima Nikya 1, Mūla Paṇṇāsa 1, Sīha,nāda Vagga 1 2 Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta The Lesser Discourse on the Lion-roar | M 11 Theme: Witnessing the true teaching and Buddhist missiology Translated & annotated by Piya Tan ©2015 0 The Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta: summary and highlights 0.1 THE LION-ROAR 0.1.1 What is a lion-roar? 0.1.1.1 The Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta opens with the Buddha encouraging us to make a lion-roar, a public witness of faith that the true liberated saints (the arhats) are found only in the Buddha’s teaching [5.1.1]. The imagery of the lion-roar is based on the well known nature of the lion, as described here, in the (Anicca) Sīha Sutta (A 2.10): 3 “The lion, bhikshus, king of the beasts, in the evening emerges from his lair. Having emerg- ed, he stretches himself, surveys the four quarters all around, roars his lion-roar thrice, and then leaves for his hunting-ground. [85] 4 Bhikshus, when the animals and creatures hear the roar of the lion, the king of the beasts, they, for the most part, are struck with fear, urgency1 and trembling.2 Those that live in holes, enter their holes; the water-dwellers head into the waters; the forest- dwellers, seek the forests; winged birds resort to the skies.3 5 Bhikshus, those royal elephants bound by stout bonds, in the villages, market towns and capitals—they break and burst their bonds, and flee about in terror, voiding and peeing. -

Nibbedhika (Pariyāya) Sutta

A 6.2.1.9 Aṅguttara Nikāya 6, Chakka Nipāta 2, Dutiya Paṇṇāsaka 1, Mahā Vagga 9 11 Nibbedhika (Pariyāya) Sutta The Discourse on (the Exposition on) Penetrating Insight | A 6.63 Theme: A novel application of the noble truths as an overview of the way to spiritual freedom Translated with notes by Piya Tan ©2003, 2011 1 Sutta highlights 1.1 This popular sutta is often quoted in the Commentaries.1 It is a summary of the whole Teaching as the Way in six parallel methods, each with six steps: sensual desire, feelings, perceptions, mental influxes, karma, and suffering —each to be understood by its definition, diversity (of manifestation), result, cessa- tion and the way to its cessation. It is a sort of extended “noble truth” formula [§13]. In fact, each of analytical schemes of the six defilements (sensual desire, etc) is built on the structure of the 4 noble truths with the additional factors of “diversity” and of “result.” The Aṅguttara Comment- ary glosses “diversity” as “various causes” (vemattatā ti nānā,kāraṇaṁ, AA 3:406). In other words, it serves as an elaboration of the 2nd noble truth, the various internal or subjective causes of dukkha. “Re- sult” (vipāka), on the other hand, shows the external or objective causes of dukkha. 1.2 The Aṅguttara Commentary takes pariyāya here to mean “cause” (kāraṇa), that is, a means of pene- trating (that is, destroying) the defilements: “It is called ‘penetrative’ (nibbedhika) because it penetrates the mass of greed, etc, which had never before been penetrated or cleaved.” (AA 3:223) The highlight of the exposition is found in these two remarkable lines of the sutta’s only verse: The thought of lust is a person’s desire: The diversely beautiful in the world remain just as they are. -

22 Indriya DEFINITION: Indriya: Literally, ―Belonging to Indra‖, a Chief Deity

Abhidharmakosa Chapter 2: Indriyas (Faculties) Overview: Chapter 2 continues the analysis of Chapter 1 in laying out the basic underlying principles of the Abhidharma approach. Chapter 2 begins with an exposition of the indriyas which continues the treatment of traditional teaching categories from Chapter 1 (which analyzed skandhas, ayatanas and dhatus). After the analysis of the indriyas (see below for summary and table), Vasubandhu lays out the dharmas associated and not associated with mind along the lines of the less traditional Panca-vastuka (five groups) formulation (this was an later Abhidharma development). To some extent, Chapter 1 covered the rupa (material form) group of dharmas, as well as the mind/consciousness (citta/vijnana) group (just 1 dharma). The unconditioned dharmas are treated in both chapter 1 and 2. Chapter 2 then unfolds the mental dharmas and the dharmas not associated with mind (which comprise the 4th skandha: samskaras). By treating the indriyas first, Vasubandhu may be trying to give a more sutra-based foundation to the exposition of the samskaras before unfolding the later Panca-vastuka formulation. After the analysis of the indriyas below, there is a study of the 75 dharmas (and some thoughts on the development of ―dharma lists‖. As the dharmas are not things, but functions or causal forces, Vasubandhu follows up the exposition of the dharmas with a treatment of causality (K48-73, see overview below). 22 Indriya DEFINITION: Indriya: literally, ―belonging to Indra‖, a chief deity. Indriya comes to connote supremacy, dominance, control, power and strength. Soothill‘s definition of the Chinese: ―根 mūla, a root, basis, origin; but when meaning an organ of sense, indriyam, a 'power', 'faculty of sense, sense, organ of sense'. -

Three Texts on Consciousness Only

THREE TEXTS ON CONSCIOUSNESS ONLY dBET Alpha PDF Version © 2017 All Rights Reserved BDK English Tripit aka 60-1, II, III THREE TEXTS ON CONSCIOUSNESS ONLY Demonstration of Consciousness Only by Hsüan-tsang The Thirty Verses on Consciousness Only by Vasubandhu The Treatise in Twenty Verses on Consciousness Only by Vasubandhu Translated from the Chinese of Hsiian-tsang (Taisho Volume 31, Numbers 1585, 1586, 1590) by Francis H. Cook Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 1999 © 1999 by Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and Numata Center for Buddhist Translation Research All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transcribed in any form or by any means —electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise— without the prior written permission of the publisher. First Printing, 1999 ISBN: 1-886439-04-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-079041 Published by Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 2620 Warring Street Berkeley, California 94704 Printed in the United States of America A Message on the Publication of the English Tripitaka The Buddhist canon is said to contain eighty-four thousand different teachings. I believe that this is because the Buddha’s basic approach was to prescribe a different treatment for every spiritual ailment, much as a doctor prescribes a different medicine for every medical ailment. Thus his teachings were always appropriate for the particu lar suffering individual and for the time at which the teaching was given, and over the ages not one of his prescriptions has failed to relieve the suffering to which it was addressed. -

Trickster-Like Teachings in Tibetan Buddhism: Shortcuts Towards Destroying Illusions

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 5(1): 1-9, 2018; Article no.ARJASS.38108 ISSN: 2456-4761 Trickster-Like Teachings in Tibetan Buddhism: Shortcuts towards Destroying Illusions Z. G. Ma1* 1California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS), California, USA. Author’s contribution The sole author designed, analyzed and interpreted and prepared the manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2018/38108 Editor(s): (1) Shiro Horiuchi, Faculty of International Tourism, Hannan University, Japan. (2) David Perez Jorge, Department of Teaching and –Educational research, University of La Laguna, Spain. Reviewers: (1) Dare Ojo Omonijo, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Nigeria. (2) Valentine Banfegha Ngalim, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon. (3) Lufanna Ching-Han Lai, Gratia Christian College, China. (4) Abraham K. Kisang, Kenyatta University, Kenya. (5) Uche A. Dike, Niger Delta University, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/22795 Received 6th November 2017 Accepted 11th January 2018 Opinion Article th Published 20 January 2018 ABSTRACT Trickster-like Dharma teachings in Tibetan Buddhism behave as a kind of shortcuts in the approach to leading people along the path of enlightenment. This essay collects three such teachings of different levels towards destroying illusions, i.e., Buddha’s silence, Guru’s paradox, and Ego’s kleshas. They are necessary as “an ace up the sleeve” for Buddha to destruct disciples’ metaphysical quagmire, for Guru to lead community toward perfect transcendence,