John Coket: Medieval Merchant of Ampton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typed By: Apb Computer Name: LTP020

LIST 42 13 October 2017 Applications Registered between 9/10/17 – 13/10/17 ST. EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk . Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/17/2053/VAR Planning Application - Variation of Condition Development Site VALID DATE: 7 of DC/16/0432/FUL to enable an extended Spring Road 06.10.2017 permitted period of playing formal football Bardwell matches from the existing permission Suffolk EXPIRY DATE: (Saturdays 10.00am - 14.30pm) to the 05.01.2018 proposed (Saturdays 10.00am - 17.00pm) for the Change of Use from Agricultural land WARD: Bardwell (Use Class Sui Generis) to Recreational Use GRID REF: (Use Class D2) for local community use for 594162 274077 PARISH: Bardwell exercise, sport and general recreation APPLICANT: Mr Peter Sanderson, Bardwell Parish Council CASE OFFICER: Gary Hancox DC/17/2107/AG1 Determination in Respect of Permitted Pinn Field VALID DATE: Agricultural Development - Agricultural Glassfield Road 11.10.2017 building housing livestock Stanton IP31 2DS EXPIRY DATE: APPLICANT: Mr Paul Claxton 08.11.2017 AGENT: Mr Ian Pick - Ian Pick Associates Ltd GRID REF: WARD: Bardwell CASE OFFICER: Jonny Rankin 595312 273166 PARISH: Bardwell DC/17/2109/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification 7no Moat House VALID DATE: Conifer (A-G on plan) Fell. -

Baptism Data Available

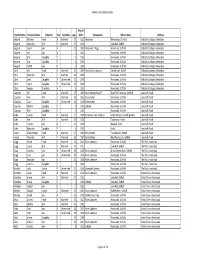

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Forest Heath District Council & St Edmundsbury Borough

F O O R }P T F N O A O H R C }P R T F A N O A O H R C Town and }CountryP Planning (Development Management Procedure) F R TST EDMUNDSBURYFOREST HEATH BOROUGHDISTRICT COUNCIL COUNCILF & O A Advert types: PlanningN (Listed Building and Conservation Areas) ACT 1990 to a Listed Building;Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development)O O setting of a Listed Building; A Conservation Area O R Notice is given that Forest HeathH District Council and St Edmundsbury Borough Council P have received the following application(s): R PLANNING AND OTHER APPLICATIONS: PUBLIC NOTICE } C P 1. DC/16/2452/VAR } T F RPROW 2. DC/16/2457/FUL T F N Bury St Edmunds (CLB, C) O A (England) Order 2015 3. DC/16/2511/FUL -Affecting a public right of way; N O A warehouse and offices, Oasis, Homefield Road, HaverhillCLB (M, PROW) O 4. DC/16/2538/FUL and DC/16/2539/LB A H , 30-32 St Johns Street, Bury St Edmunds (C, SLB) -Within the curtilage of a Listed Building; O R (Amendment) OrderH R C P5. DC/16/2619/FULmain entrance and internal alterations, Hall Barn, Bury Road, Great LBDCThurlow, Haverhill R } (LB, C, PROW) C P T6. DCON(A)/SE/13/0902 - Variation of condition 2 of DC/16/0786/FUL, 87 Guildhall Street, } Little Livermere, Bury St Edmunds (CLB) F R -Listed Building discharge conditions; T F A 7. DCON(A)/SE/13/0938 - Conversion of offices to warehouse and extension to create new N Gurteen And Sons Ltd, Chauntry Mills, High Street, Haverhill (LBDC) A O - Conversion of retail space in to 6 no. -

Role Description LVNB Team Vicar 50% Fte 2019

Role description signed off by: Archdeacon of Sudbury Date: April 2019 To be reviewed 6 months after commencement of the appointment, and at each Ministerial Development Review, alongside the setting of objectives. 1 Details of post Role title Team Vicar 50% fte, held in plurality with Priest in Charge 50% fte Barrow Benefice Name of benefices Lark Valley & North Bury Team (LVNB) Deanery Thingoe Archdeaconry Sudbury Initial point of contact on terms of Archdeacon of Sudbury service 2 Role purpose General To share with the Bishop and the Team Rector both in the cure of souls and in responsibility, under God, for growing the Kingdom. To ensure that the church communities in the benefice flourish and engage positively with ‘Growing in God’ and the Diocesan Vision and Strategy. To work having regard to the calling and responsibilities of the clergy as described in the Canons, the Ordinal, the Code of Professional Conduct for the Clergy and other relevant legislation. To collaborate within the deanery both in current mission and ministry and, through the deanery plan, in such reshaping of ministry as resources and opportunities may require. To attend Deanery Chapter and Deanery Synod and to play a full part in the wider life of the deanery. To work with the ordained and lay colleagues as set out in their individual role descriptions and work agreements, and to ensure that, where relevant, they have working agreements which are reviewed. This involves discerning and developing the gifts and ministries of all members of the congregations. To work with the PCCs towards the development of the local church as described in the benefice profile, and to review those needs with them. -

Little Livermere

1. Parish : Little Livermere Meaning: Lake where rushes or iris grow 2. Hundred: Blackbourn Deanery: Blackbourn (–1930), Thingoe (1930–) Union: Thingoe (1836–1907), Bury St Edmunds (1907–1930) RDC/UDC: (W. Suffolk) Thingoe RD (–1974), St Edmundsbury DC (1974–) Other administrative details: Abolished ecclesiastically to create Ampton and Little Livermere 1946 Blackbourn Petty Sessional Division Bury St Edmunds County Court District 3. Area: 1,409 acres of land, 28 acres water (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Deep well drained sandy soils, in places very acid. Risk wind erosion. b. Deep well drained sandy soils, some very acid especially under heath and woodland. Risk wind erosion. c. Deep permeable sand and peat soils affected by groundwater. Risk of winter flooding and wind erosion near river. 5. Types of farming: 1086 Livermere: 1 acre meadow 1283 123 quarters to crops (984 bushels), 14 head horse, 54 cattle, 17 pigs, 649 sheep* 1500–1640 Thirsk: Sheep-corn region, sheep main fertilising agent, bred for fattening. Barley main cash crop. 1818 Marshall: Management varies with condition of sandy soils. Rotation usually turnip, barley, clover, wheat or turnips as preparation for corn and grass. 1937 Main crops: Wheat, barley, oats, peas, turnips 1969 Trist: Barley and sugar beet are the main crops with some rye grown on poorer lands and a little wheat, herbage seeds and carrots. 1 Livermere Charolais Ltd.: pedigree herd of prize winning cattle founded c.1971, sold c.1981. *‘A Suffolk Hundred in 1283’, by E. Powell (1910). Concentrates on Blackbourn Hundred. Gives land usage, livestock and the taxes paid. 6. -

1. Parish: Stanningfield

1. Parish: Stanningfield Meaning: Stony field. 2. Hundred: Thedwastre Deanery: Thedwastre (−1884), Horningsheath (1884−1914), Horringer (1914−1972), Lavenham (1972−) Union: Thingoe (1836−1907), Bury St. Edmunds (1907−1930) RDC/UDC: Thingoe RD (−1974), St. Edmundsbury DC (1974−) Other administrative details: 1884 Civil boundary change Thingoe and Thedwastre Petty Sessional division. Bury St. Edmunds County Court district 3. Area: 1469 acres (1912) 4. Soils: Slowly permeable calcareous/non calcareous clay soils. Slight risk water erosion. 5. Types of farming: 1086 15 acres meadow, 1 mill 1500–1640 Thirsk: Wood-pasture region. Mainly pasture, meadow, engaged in rearing and dairying with some pig keeping, horse breeding and poultry. Crops mainly barley with some wheat, rye, oats, peas, vetches, hops and occasionally hemp. 1818 Marshall: Course of crops varies usually including summer fallow as preparation for corn products 1937 Main crops: Wheat, sugar beet, oats, barley 1969 Trist: More intensive cereal growing and sugar beet. 6. Enclosure: 7. Settlement: 1958 Extremely small points of habitation. These are at Hoggards Green and at the church. Scattered farms. Roman road forms portion of S.E. boundary. Inhabited houses: 1674 – 22, 1801 – 34, 1851 – 66, 1871 – 75, 1901 – 61, 1951 – 75, 1981 – 155. 1 8. Communications: Road: To Gt. Whelnetham, Lawshall and Cockfield. Length of Roman road. 1891 Carrier passes through to Bury St. Edmunds on Wednesday and Saturday. Rail: 1891 2 miles Cockfield station. Bury St. Edmunds to Long Melford line opened 1865, closed passengers 1961, closed goods 1965 9. Population: 1086 − 26 recorded 1327 − 18 taxpayers paid £3 2s. (includes Bradfield Combust) 1524 − 15 taxpayers paid £3 2s. -

Archaeology in Suffolk 2015 Compiled by F Minter Drawings D Wreathall

611 ARCHAEOLOGY IN SUFFOLK 2015 compiled by FAYE MINTER with object drawings by DONNA WREATHALL THIS IS A selection of the new discoveries reported in 2015. Information on these has been incorporated into the Suffolk Historic Environment Record (formerly the Sites and Monuments Record), which is maintained by the Archaeological Service of Suffolk County Council at Bury St Edmunds. Where available, the Record number is quoted at the beginning of each entry. The Suffolk Historic Environment Record is now partially accessible online via the Suffolk Heritage Explorer web pages (https://heritage.suffolk.gov.uk/) or the Heritage Gateway (www.heritagegateway.org.uk). This list is also available on the Suffolk Heritage Explorer site and many of the excavation/evaluation reports are now also available online via the Archaeological Data Service (http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/greylit/). Most of the finds are now being recorded through the national Portable Antiquities Scheme, the Suffolk part of which is also based in the Archaeological Service of Suffolk County Council. Further details and images of many of the finds can be found on the Scheme’s website (http://finds.org.uk/database) and for many of the finds listed here the PAS reference number is included in the text. During 2015 the PAS finds in Suffolk were recorded by Andrew Brown, Anna Booth and Faye Minter. Following requests from metal detector users, we have removed all grid references from entries concerning finds reported by them. We continue to be grateful to all those who contribute information for this annual list. Abbreviations: CIC Community Interest Company Mdf Metal detector find PAS Portable Antiquities Scheme (see above). -

WSC Planning Applications 51/19

LIST 51 20 December 2019 Applications Registered between 16.12.2019 – 20.12.2019 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk. Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Note: Representations on Brownfield Permission in Principle applications and/or associated Technical Details Consent applications must arrive not later than 14 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/19/2449/EIASCR EIA Screening Opinion under Regulation 6 Proposed Development VALID DATE: (1) of the Environmental Impact Assessment At 18.12.2019 Regulations 2017 on the matter of whether St Genevieve Lakes or not the proposed development is Road From Bury Road EXPIRY DATE: considered that there are likely significant To B1106 08.01.2020 environmental impacts for which an Timworth Environmental Statement would be required Suffolk WARD: Pakenham & - 65no. holiday lodges Troston APPLICANT: Mr Ian Brooker PARISH: Ampton, Little GRID REF: Livermere & Timworth 585161 269093 CASE OFFICER: Penny Mills DC/19/2428/PIP Permission in Principal - 2-5no. dwellings Land Rear Of VALID DATE: Barrow Road 12.12.2019 -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Suffolk County Council

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Suffolk County Council Report to The Electoral Commission July 2004 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. Report No. 374 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Summary 7 1 Introduction 21 2 Current electoral arrangements 25 3 Draft recommendation 35 4 Responses to consultation 37 5 Analysis and final recommendations 41 6 What happens next? 97 Appendix A Final recommendations for Suffolk: Detailed mapping 99 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to The Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI No. 3962). The Order also transferred to The Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. -

Hawstead Census 1861.Pdf

HAWSTEAD CENSUS 1861 Year of Family Name Personal Name Relation Sex Condition Age Birth Occupation Where Born Address Sargent Meshack Head M Married 39 1822 Shepherd Whepstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Mary Ann Wife F Married 35 1826 Lawshall, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Daniel Son M 12 1849 Shepherd's Page Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent John Son M 9 1852 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Ellen Daughter F 6 1855 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Ann Daughter F 4 1857 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Robert Son M 2 1859 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark John Head M Married 57 1804 Agricultural Labourer Chedburgh. Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark Mary Ann Wife F Married 55 1806 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark Sarah Daughter F Unmarried 19 1842 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark Harriet Daughter F Unmarried 15 1846 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark George Grandson M 8 1853 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Cawston John Head M Married 55 1806 Farm Steward Bailiff Bradfield Combust, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Ann Wife F Married 48 1813 Dressmaker Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Susan Daughter F Unmarried 18 1843 Dressmaker Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Martha Daughter F 8 1853 Scholar Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Ellen Daughter F 2 1859 Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Buker Charles Head M Married 41 1820 Pensioner -

The Bury St Edmunds

THE BURY ST EDMUNDS Issue 43 January 2021 Delivered from 28th January Also covering - Horringer Westley - The Fornhams - Great Barton AAdvertisingdvertising SSales:ales: 0012841284 559292 449191 wwww.flww.fl yyeronline.co.ukeronline.co.uk The Flyer From your MP Jo Churchill popular that they have had to take and hospitality and the start of a new incredible small businesses. The lure on bigger premises. We have some year, I am keen for us to make 2021 of excellent Suffolk Cheese, Suffolk wonderful traders across Suffolk, and I the Year of the High Street. Putting brewed beer and cracking Suffolk Pork would encourage constituents to visit the heart back into the centre of our often draws many shoppers on to high as many as possible. communities. Our high streets have streets and into our eateries in our towns and villages. faced unprecedented challenges in I understand that during the pandemic the past few years, and ultimately the many more of us became reliant on Living in Suffolk means we can pandemic has unfortunately hastened online shopping as a necessity, due to sometimes be truly spoilt with the the demise of several well-known the lockdown. However, we are now quality and abundance of locally brands. Nevertheless, new businesses able to visit our shops, restaurants, sourced goods. My mission in 2021 are appearing and many of them cafes and bars in person, all who have is to be a shop Suffolk, shop local exciting small independent traders. worked hard to ensure they have champion, encouraging as many a safe COVID secure environment. -

SEBC Planning Applications 17/17

LIST 17 21 April 2017 Applications Registered between 17/4/17 – 21/4/17 ST. EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk . Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/17/0246/FUL Planning Application - Retention of 1no. The Academy Health VALID DATE: portable cabin And Fitness Centre 18.04.2017 Church Farm APPLICANT: Mr Phillip Smith Church Road EXPIRY DATE: Barrow 13.06.2017 IP29 5AX CASE OFFICER: James Claxton WARD: Barrow GRID REF: PARISH: Barrow Cum 575966 264556 Denham DC/17/0725/HH Householder Planning Application - Detached Oldfields VALID DATE: garden/machine storage buliding Main Road 07.04.2017 Bradfield Combust APPLICANT: Mr And Mrs Smith Bury St Edmunds EXPIRY DATE: AGENT: Dean Jay Pearce Architectural Suffolk 02.06.2017 Design And Planning LTD IP30 0LS WARD: Rougham CASE OFFICER: Karen Littlechild GRID REF: PARISH: Bradfield 589053 255615 Combust With Stanningfield DC/17/0734/HH Householder Planning Application - (i) Single 1 Rookwood Farm VALID DATE: storey front and rear extensions (ii) two Cottages 19.04.2017