Nation-Building and Australian Popular Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2011 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2011 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 MAKING MIRRORS Gotye <P>2 ELEV/UMA ELEVENCD101 2 REECE MASTIN Reece Mastin <P> SME 88691916002 3 THE BEST OF COLD CHISEL - ALL FOR YOU Cold Chisel <P> WAR 5249889762 4 ROY Damien Leith <P> SME 88697892492 5 MOONFIRE Boy & Bear <P> ISL/UMA 2777355 6 RRAKALA Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu <G> SFM/MGM SFGU110402 7 DOWN THE WAY Angus & Julia Stone <P>3 CAP/EMI 6263842 8 SEEKER LOVER KEEPER Seeker Lover Keeper <G> DEW/UMA DEW9000330 9 THE LIFE OF RILEY Drapht <G> AYEM/SME AYEMS001 10 BIRDS OF TOKYO Birds Of Tokyo <P> CAP/EMI 6473012 11 WHITE HEAT: 30 HITS Icehouse <G> DIVA/UMA DIVAU1015C 12 BLUE SKY BLUE Pete Murray <G> SME 88697856202 13 TWENTY TEN Guy Sebastian <P> SME 88697800722 14 FALLING & FLYING 360 SMR/EMI SOLM8005 15 PRISONER The Jezabels <G> IDP/MGM JEZ004 16 YES I AM Jack Vidgen <G> SME 88697968532 17 ULTIMATE HITS Lee Kernaghan ABC/UMA 8800919 18 ALTIYAN CHILDS Altiyan Childs <P> SME 88697818642 19 RUNNING ON AIR Bliss N Eso <P> ILL/UMA ILL034CD 20 THE VERY VERY BEST OF CROWDED HOUSE Crowded House <G> CAP/EMI 9174032 21 GILGAMESH Gypsy & The Cat <G> SME 88697806792 22 SONGS FROM THE HEART Mark Vincent SME 88697927992 23 FOOTPRINTS - THE BEST OF POWDERFINGER 2001-2011 Powderfinger <G> UMA 2777141 24 THE ACOUSTIC CHAPEL SESSIONS John Farnham SME 88697969872 25 FINGERPRINTS & FOOTPRINTS Powderfinger UMA 2787366 26 GET 'EM GIRLS Jessica Mauboy <G> SME 88697784472 27 GHOSTS OF THE PAST Eskimo Joe WAR 5249871942 28 TO THE HORSES Lanie Lane IVY/UMA IVY121 29 GET CLOSER Keith Urban <G> CAP/EMI 9474212 30 LET'S GO David Campbell SME 88697987582 31 THE ENDING IS JUST THE BEGINNING REPEATING The Living End <G> DEW/UMA DEW9000353 32 THE EXPERIMENT Art vs. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

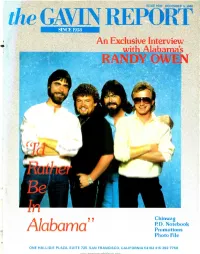

The GAVIN REP SINCE 1958 an Exclusive Interview 'S

IS3UE 1635 OECEIWBEF 5, 1986 the GAVIN REP SINCE 1958 An Exclusive Interview 's Chinwag P.D. Notebook Alabama" Promotions Photo File ONE HALLIDIE PLAZA, SUITE 725 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA E4102 4`5.392.7750 www.americanradiohistory.com P A U L S I M O N G R A C E L A N D ©1986 Warner Bros. Records Inc. From the album Graceland COEC CIO FIATE YOVFR PLAYLIST WITH THESE FOVFR SINGLES. mowÁ F.MVY R1 :AT HErn T oft!1"11:.:.;i From the album Rod Stewart www.americanradiohistory.com the GAVIN REPORT Editor: Dave Sholin TOP 40 CHART Reports accepted Mondays at SAM through 11AM Wednesdays Station Reporting Phone (415)392 -7750 MOST ADDED TW 2 2 1 BRUCE HORNSBY & THE RANGE - The Way It Is (RCA) 5 3 2 WANG CHUNG - Have Fun Tonight (Geffen) 8 4 3 BANGLES - Walk Like An Egyptian (Columbia) 1 1 4 Huey Lewis & The News - Hip To Be Square (Chrysalis) 10 7 5 PRETENDERS - Don't Get Me Wrong ( Sire/Warner Bros.) 14 8 6 DURAN DURAN - Notorious (Capitol) 15 12 7 SURVIVOR - Is This Love (Scotti Bros.) A BOSTON 13 11 8 HOWARD JONES - You Know I Love You...Don't You? (Elektra) Were Ready 17 13 9 GENESIS - Land Of Confusion (Atlantic) (MCA) 24 17 10 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN- War (Columbia) 120 Adds 19 15 11 J OBBIE NEVIL - C'est La Vie (Manhattan) 3 5 12 Peter Cetera & Amy Grant - The Next Time I Fall In Love (Full Moon/W.B.) 27 19 13 GREGORY ABBOTT - Shake You Down (Columbia) LIONEL RICHIE 12 14 14 Billy Idol - To Be A Lover (Chrysalis) Ballerina Girl 25 22 15 GLASS TIGER - Someday (Manhattan) (Motown) 21 18 16 BILLY OCEAN - Love Is Forever (Jive/Arista) 70 Adds 22 20 17 BEN E. -

Sydney 18 Våra Medlemmar

AZeelAnd.se UNDER A ZeeländskA vänskApsföreningen www.AustrAlien-ny DAustrAlisk A ny WN nr 4 / 2012 the sAints AustrAlien där och sverige regnskogen långt emellAn men möter revet ändå likA dykning på nyA ZeelAnd • NYHETER • samaRbETE mEd sTudiEfRämjaNdET • KaNgoRoo HoppET • LäsaRfRågoR Besök vänskApsföreningens nyA hemsidA på hemsidan hittar du senaste nytt om evenemang, nyheter, medlemsförmåner och tips. du kan läsa artiklar, reseskildringar och få information om working holiday, visum mm. www.AustrAlien-nyAZeelAnd.se Bli medlem i AustrAliskA nyA ZeeländskA vänskApsföreningen medlemsavgift 200:- kalenderår. förutom vår medlemstidning erhåller du en mängd rabatter hos företag och föreningar som vi samarbetar med. att bli medlem utvecklar och lönar sig! inbetalning till plusgiro konto 54 81 31-2. uppge namn, ev. medlemsnummer och e-postadress. 2 D WN UNDER Det sprakar från elden i kakelugnen och förs- ta adventsljuset är tänt när jag skriver denna ledare. Den första snön har redan fallit, det nal- kas mot jul och vi närmar oss ett nytt och spän- nande år. År 2012 har varit alldeles fantastiskt oRdföRaNdEN HaR oRdET 4 för egen del. Jag har börjat på ett nytt arbete som verksamhetsutvecklare hos Studiefrämjan- däR REgNsKogEN möTER REvET 5 det Bohuslän Norra med inriktning på musik och kultur. Vågar nog påstå att det är det mest inspirerande arbete KaNgoRoo HoppET 7 jag hittills haft. Inspirerande är också att just Studiefrämjandet och Vänskapsföreningen under hösten inlett ett samarbete som jag hoppas DykniNg på NYa ZEELaNd 8 ni kan ha mycket glädje och nytta av. Som vanligt går man omkring och längtar till vänner och platser på andra sidan jordklotet. -

The Best Drum and Bass Songs

The best drum and bass songs Listen to the UK legend's unranked list of the 41 best drum'n'bass songs ever below, and be sure to also check out his latest release "What. When it comes to drum and bass, it doesn't get more iconic than Andy C. Listen to the UK DnB legend's unranked list of the 41 best drum'n'bass. By the end of the noughties Drum & Bass was one of the UK's biggest music scenes, Capital Xtra has complied some of the biggest D&B tracks of all time. feast that not only complimented the massively popular original, but bettered it. Download and listen to new, exclusive, electronic dance music and house tracks. Available on mp3 and wav at the world's largest store for DJs. The legendary producer, DJ, artist, actor and more schools us on some of the best drum and bass has to offer. Read a 10 best list of drum and bass tracks from longstanding DJ, producer, and label- head Doc Scott. Out now, it's the first ever fully drum & bass remix EP Moby has had Ten of the best drum & bass tracks of all time according to Moby himself. Simply the best Drum & Bass tunes of all time as voted and added by Ranker users.I've started us off with 40 of my favorite tracks from across old and new (now. The top 10 Drum and Bass tracks on the website. Best Drum & Bass Mix | Best Party, Dance & DnB Charts Remixes Of Popular Songs by Monkey. -

Australia (Ascot)

Race Number Australia (Ascot) Thursday, April 9, 2020 1:20am EDT AMELIA PARK (RS0LY) ($15K) 12:20am CDT 1A 5 f Apprentices Can Claim 3yo NMW1Y 10:20pm PDT W, P, S, Ex, DD, Tri, Super Selections 6 - 1 - 3 - 4 3yo b Gelding $25K firm 0: 0- 0- 0 River Beau (132) 5 To 2 Sire: Snippetson LIFE 7: 1- 3- 1 good 7: 1- 3- 1 1. Owner: K Beauglehole & Mrs P Beauglehole Dam: Peggie's Louise Trk 3: 0- 2- 0 soft 0: 0- 0- 0 Lime Green, Black Diamonds And Cuffs Dam Sire: Oratorio Dist 2: 0- 1- 0 heavy 0: 0- 0- 0 pp 1 Jason Whiting (L50 5-14 10%-38%, L350 30-119 9%-43%) Trainer: B V Watkins (Capel) (L50 4-26 8%-60%, L350 41-138 12%-51%) Date Course SOT Class Dst S1 S2 Rtime SR St S 6f 4f Trn FP Mrg Jockey (PP) Wt (lbs) Off 4Apr20 ASC-M GD 3yo($43K)Bm57+ 5 1/2 f 0:284 0:34 3 1:03 3 80 10/ 5- - 5- 5 2- 0.8 J Whiting (3) 129 11.00 1- Cliffs Of Comfort (126), 2- River Beau (129), 3- Tommy Blue (131) 25Mar20 ASC-M GD 3yo($18K)Nmw1y 5 f 0:24 0:34 0:58 74 7/ 7- - 7- 7 2- 0.2 J Whiting (4) 131 17.00 1- Semigel (130), 2- River Beau (131), 3- At War (130) 7Mar20 ASC-M GD 3yo($43K)Bm62+ 5 f 0:242 0:34 0:58 2 50 9/ 4- - - 3 7- 6.5 J Whiting (6) 125 31.00 1- Laverrod (132), 2- Snippiranha (122), 3- Comes A Time (126) 24Feb20 LHL-C GD Barrier Trial 4 3/4 f 0:57 7/ - - - 2- 2.8 J Whiting (2) 1- Laverrod, 2- River Beau, 3- Strasmore 15Dec19 BUB-P GD 3yo+($15K)Cl1 6 f 0:36 0:35 1 1:11 2 69 10/ 5- - 5- 6 4- 2.3 J Whiting (4) 130 2.75 1- Cocky Dodd (129), 2- Great Charade (126), 3- Ladies Of London (129) 4Dec19 BUB-P GD 3yo+($15K)Cl1 5 1/2 f 0:302 0:35 1:05 3 75 9/ 7- - -

Concert and Music Performances Ps48

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection CONCERT AND MUSIC PERFORMANCES PS48 This collection of posters is available to view at the State Library of Western Australia. To view items in this list, contact the State Library of Western Australia Search the State Library of Western Australia’s catalogue Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1975 April - September 1975 PS48/1975/1 Perth Concert Hall ABC 1975 Youth Concerts Various Reverse: artists 91 x 30 cm appearing and programme 1979 7 - 8 September 1979 PS48/1979/1 Perth Concert Hall NHK Symphony Orchestra The Symphony Orchestra of Presented by The 78 x 56 cm the Japan Broadcasting Japan Foundation and Corporation the Western Australia150th Anniversary Board in association with the Consulate-General of Japan, NHK and Hoso- Bunka Foundation. 1981 16 October 1981 PS48/1981/1 Octagon Theatre Best of Polish variety (in Paulos Raptis, Irena Santor, Three hours of 79 x 59 cm Polish) Karol Nicze, Tadeusz Ross. beautiful songs, music and humour 1989 31 December 1989 PS48/1989/1 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Elisa Wilson Embleton (soprano), John Kessey (tenor) Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1990 7, 20 April 1990 PS48/1990/1 Art Gallery and Fly Artists in Sound “from the Ros Bandt & Sasha EVOS New Music By Night greenhouse” Bodganowitsch series 31 December 1990 PS48/1990/2 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Emma Embleton Lyons & Lisa Brown (soprano), Anson Austin (tenor), Earl Reeve (compere) 2 November 1990 PS48/1990/3 Aquinas College Sounds of peace Nawang Khechog (Tibetan Tour of the 14th Dalai 42 x 30 cm Chapel bamboo flute & didjeridoo Lama player). -

Perth Music Interviews Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Amber Flynn

Perth Music Interviews Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Amber Flynn (Rabbit Island) Sean O’Neill (Hang on Saint Christopher) Bill Darby David Craddock (Davey Craddock and the Spectacles) Scott Tomlinson (Kill Teen Angst) Thomas Mathieson (Mathas) Joe Bludge (The Painkillers) Tracey Read (The Wine Dark Sea) Rob Schifferli (The Leap Year) Chris Cobilis Andy Blaikie by Benedict Moleta December 2011 This collection of interviews was put together over the course of 2011. Some of these people have been involved in music for ten years or more, others not so long. The idea was to discuss background and development, as well as current and long-term musical projects. Benedict Moleta [email protected] Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Were you born in Perth ? Yeah, I was born in Mt Lawley. You've been working on a music documentary for a while now, what's it about ? I started shooting footage mid 2008. I'm making a feature documentary about a bunch of bands over a period of time, it's an unscientific longitudinal study of sorts. It's a long process because I want to make an observational documentary with the narrative structure of a fiction film. I'm trying to capture a coming of age cliché but character arcs take a lot longer in real life. I remember reading once that rites of passage are good things to structure narratives around, so that's what I'm going to do, who am I to argue with a text book? Fair call. I guess one of the characteristics of bands developing or "coming of age" is that things can emerge, change, pass away and be reconfigured quickly. -

PUNK/ASKĒSIS by Robert Kenneth Richardson a Dissertation

PUNK/ASKĒSIS By Robert Kenneth Richardson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Program in American Studies MAY 2014 © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of Robert Richardson find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Carol Siegel, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________ Thomas Vernon Reed, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Kristin Arola, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Laws are like sausages,” Otto von Bismarck once famously said. “It is better not to see them being made.” To laws and sausages, I would add the dissertation. But, they do get made. I am grateful for the support and guidance I have received during this process from Carol Siegel, my chair and friend, who continues to inspire me with her deep sense of humanity, her astute insights into a broad range of academic theory and her relentless commitment through her life and work to making what can only be described as a profoundly positive contribution to the nurturing and nourishing of young talent. I would also like to thank T.V. Reed who, as the Director of American Studies, was instrumental in my ending up in this program in the first place and Kristin Arola who, without hesitation or reservation, kindly agreed to sign on to the committee at T.V.’s request, and who very quickly put me on to a piece of theory that would became one of the analytical cornerstones of this work and my thinking about it. -

Review: Barefoot in the Park Montessorj New School Students

4«SIDELINES Friday, November 22, 1985 Features/Entertainment The metamorphosis from girl to The song, with drums and bass from you it froze me deep inside." woman is the subject of "When She setting a steady beat, focuses on the The following "Kyoto Song" is an Was a Girl," a haunting look at so- problem of irresponsible writers, oriental-influenced tune tinged ciety and its insecurities juxtaposed spreading vicious rumors about with sensuality in its use of a slow against a wall of reverberating people. The line: pace and lush, exotic instrumenta- guitars and a driving rhythm sec- "Sometimes words so innocent, cut tion backing up Smith's broken tion. so deep," voice which sings of a strange This maturity probably governed reveals the band's concern for the dream: "A nightmare of you/Of death in the choice of covering the Bob power of the media. The song, with the pool/I see no further now than Dylan classic "Cod on Our Side." its distinct 60s pop sound, reminds Musically, the sound leans toward one of Paul Revere and the Raiders. this dream." The hard, Latin influences of China-era Red Rockers, while Side one ends with "Like Wow- "The Blood" and the slow, sweet Wire Train Kevin Hunter's lackadaisical vocal Hoodoo Gurus Wipeout," a heavily American-in- The Cure melody of "Six Different Wavs" dis- delivery waters down Dylan's biting fluenced song with a very catchy Between Two Mars Needs Guitars play the diverse musical styles for social commentary. chorus, another characteristic of The Head On Words And though Hunters voice is Big Time 60s rock. -

The Melbourne Punk Scene in Australia's Independent Music History

ANZCA09 Communication, Creativity and Global Citizenship. Brisbane, July 2009 The Melbourne Punk Scene in Australia’s Independent Music History Morgan Langdon La Trobe University [email protected] Morgan Langdon completed her Honours in Media Studies at La Trobe University. This paper is an excerpt from her thesis on the history of independent music culture in Melbourne. She plans to begin her PhD in 2010. Abstract The existence of independent music communities and culture within Australia’s major cities today is largely attributed to the introduction of punk in the late 1970s. Among the inner city youth, a tiny subculture emerged around this sprawling, haphazard style of music that was quickly dismissed by the major players in the Australian music industry as bereft of commercial possibilities. Left to its own devices, punk was forced to rely solely on the strength of the independent music network to release some of the most original music of the era and lay the foundations for a celebrated musical culture. This paper examines the factors that contributed to and influenced the early Australian punk scenes, focusing in particular on Melbourne between 1975 and 1981. It shows that the emergence and characteristics of independent music communities within individual cities can be attributed to the existence of certain factors and institutions, both external and internal to the city. Keywords Australian music history, subculture, punk, independent music. Introduction In 1986, the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal published the results of an inquiry into the importance of the broadcasting quota for local music content. Throughout this inquiry, investigations are made into the existence of a distinctly Australian “sound”.