Managing Your Woodlands: Online and Interactive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plans DK00123.Pdf Doc. Type: Plans Description: Milling, Leveling, Patching, Resurfacing, Shoulder Reconstruction, and Pavement Markings

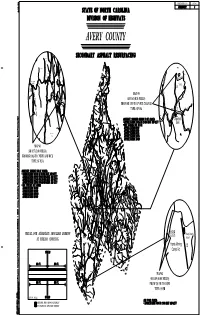

9 PROJECT REFERENCE NO. SHEET NO. 9 / 7 11CR.20061.22 1 1 / 8 STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA DIVISION OF HIGHWAYS AVERY COUNTY T r i c e F o r k M 1160 t R d .32 Va SECONDARY ASPHALT RESURFACING l Fork Mountain e Rd Z 5 Elevation 3970 .1 1159 C a .4 l h 5 o W u n AT H A 321 U o % G l 1159 A l o .4 w 1 C i . t 5 1180 y 2 Fork Mtn Cem Rd 1316 F L lat Perry Ridge Spr 4 ings i Rd 3 . m 1 i .98 t . R 2 I 0 0 V E 1 . R 1 d R . Fork Mountain le 24 H a 1162 Cemetery V F Mount Gilead . Baptist 1 1163 5 5 1159 C 2 Cliff Hill .32 . i t y very County A 9 d 3.8 R 1157 L riculture e Ag 321 al i % D Z m tnut 1 s Elevation 3880 i .01 e t 8 h .0O3 . C 1 l . 1157 d 4 T 1 1.63 o Beech Valley e Baptist Riv .30 F 1314 Ivey Heights .2 e Harmon Gap .65 6 r Road R Harmon - Flat Springs 1314 Dave Gap e y Cemetery e k d c Flat Springs u Baptist B 1185 H 1312 Ashley Chapel 1158 1317 F White Oak Road Baptist Stone y s ing pr Creek Rd. .50 S d 1 a .5 Ho o 1157 llow Road 1316 R Cemetery t R a IVE l R F B uc O ke l Norris Ward Cemetery ye H F d H 2.45 1313 25 T 1157 . -

Forests in Focus

FORESTSAMERICAN WINTER/SPRING 2019 Forests in Focus PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS See the inspiring photography that earned top honors in our annual Forests in Focus photo contest BE PART OF THE SOLUTION JOIN AMERICAN FORESTS With a membership gift of $25 or more, you’ll receive the following benefits: 8 Satisfaction and Pride. Know your gift will be used wisely to restore America’s forests to health and resiliency. 8 Annual Membership Card. Carry this with you to signify your commitment to American Forests. 8 Magazine Subscription. Read and share our award-winning, colorful and informative publication. 8 Merchandise Discounts. Shop with periodic members-only discounts from our Corporate Partners. 8 Invitations to Special Events. Be the first to be notified about special events and volunteer opportunities in your area. 8 Insider Updates on Our Work. Stay informed about the impact your gifts are having on our critical work and progress. ■ Make a difference for forests and the world. Become a member today! www.americanforests.org/ways-to-give/membership AF_FP Ads.indd 1 11/8/18 10:38 AM VOL. 125, NO. 1 CONTENTS WINTER/SPRING 2019 Departments 2 Offshoots A word from our President & CEO 4 Treelines PROJECT SHOWCASES: Read about our work planting trees for healing and nurturing in a Boston community and restoring fire-stricken land in the San Bernardino Mountains. FROM THE FIELD: From Texas to Baltimore, follow what we’ve been 32 up to in the field. PROFILES: Learn about our partnership with Alliance Data and how two of our supporters are returning to their roots by being involved in conservation. -

OUR ROOTS RUN DEEP 2019 Year in Review AMERICAN FORESTS’ IMPACT

OUR ROOTS RUN DEEP 2019 Year In Review AMERICAN FORESTS’ IMPACT WILDLIFE NORTHERN ROCKIES AND CASCADES WATER PEOPLE SIERRA NEVADAS AND SOUTHERN CA RANGES LOWER RIO GRANDE VALLEY YOUR VISION OUR MISSION OUR ROOTS RUN DEEP here at American Forests. Throughout our 144-year history, we have tackled global challenges with small actions done again and again: like planting trees. Best of all, planting trees and caring for forests has a role for everyone, from cities to rural communities. With your help, American NORTHERNForests is empowering people to take action and make our GREAT LAKEScountry stronger together. LAKE But our work today is more urgent and complexCHAMPLAIN than ever. Thanks to our partners and donors, we’re tappingBASIN our deep PEOPLE roots in science, forestry, policy and CLIMATEmovement leadership to overcome forest threats like drought and fire made worse by climate change. When we take care of our forests, they take care of us by providing water, wildlife, jobs and even the ability to slow climate change through natural carbon capture. But our challenges go beyond the environment. America has APPALACHIANgrowing inequities across lines of race and income that include ANDurban OZARKS tree cover. I am proud that our new push for Tree Equity is building a movement to give every person the benefits of city trees for health, wealth and protection from climate change. With your help, we have stretched in new ways. We have published scientific breakthroughs on forest soil carbon and developed new ways to link underserved communities into urban forestrySOUTHERN careers. We are stepping up to plant more trees PIEDMONT and innovateAND climate-resilient PLAINS planting techniques with new field staff around the country. -

The History of Fire in the Southern United States

Special Section on Fire Human Ecology The History of Fire in the Southern United States Cynthia Fowler Wofford College Spartanburg, SC1 Evelyn Konopik USDA Forest Service Asheville, NC2 Abstract ern Appalachians, and Ozark-Ouachita Highlands. Using this holistic framework, we consider “both ends of the fire stick” Anthropogenic fires have been a key form of disturbance (Vayda 2005) examining elements of fire use by each cultur- in southern ecosystems for more than 10,000 years. Archae- al group that has inhabited the South and its effects on south- ological and ethnohistorical information reveal general pat- ern ecosystems. terns in fire use during the five major cultural periods in the South; these are Native American prehistory, early European Table 1. Major Periods of Human-Caused Fire Regimes in the settlement, industrialization, fire suppression, and fire man- South agement. Major shifts in cultural traditions are linked to sig- FIRE Native Early Industrial- Fire Fire nificant transitions in fire regimes. A holistic approach to fire REGIME American European ization Suppression Management ecology is necessary for illuminating the multiple, complex Prehistory Settlers links between the cultural history of the South and the evolu- DATES 12,500 BP 1500s AD 1800s to 1920s to 1940s/80s tion of southern ecosystems. The web of connections between to 1500s to1700s 1900s 1940s/1980s to Present history, society, politics, economy, and ecology are inherent AD AD to the phenomena of fire. TYPICAL Low Low Stand Federal Prescribed BURNS intensity intensity replacing lands fires of brush fires brush fires fires set protected mixed Keywords: fire, culture, Native Americans, US South mainly for by loggers from fire intensity and agricultural and farmers frequency A Holistic View of People and Fire purposes Written documents that address fire ecology in the South include more than 380 years of publications, ranging from The Native American Contribution to Prehistoric Fire Smith’s 1625 monograph to Kennard’s 2005 essay. -

Urban Forest Assessments Resource Guide

Trees in cities, a main component of a city’s urban forest, contribute significantly to human health and environmental quality. Urban forest ecosystem assessments are a key tool to help quantify the benefits that trees and urban forests provide, advancing our understanding of these valuable resources. Over the years, a variety of assessment tools have been developed to help us better understand the benefits that urban forests provide and to quantify them into measurable metrics. The results they provide are extremely useful in helping to improve urban forest policies on all levels, inform planning and management, track environmental changes over time and determine how trees affect the environment, which consequently enhances human health. American Forests, with grant support from the U.S. Forest Service’s Urban and Community Forestry Program, developed this resource guide to provide a framework for practitioners interested in doing urban forest ecosystem assessments. This guide is divided into three main sections designed to walk you through the process of selecting the best urban forest assessment tool for your needs and project. In this guide, you will find: Urban Forest Management, which explains urban forest management and the tools used for effective management How to Choose an Urban Forests Ecosystem Assessment Tool, which details the series of questions you need to answer before selecting a tool Urban Forest Ecosystem Assessment Tools, which offers descriptions and usage tips for the most common and popular assessment tools available Urban Forest Management Many of the best urban forest programs in the country have created and regularly use an Urban Forest Management Plan (UFMP) to define the scope and methodology for accomplishing urban forestry goals. -

Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities

4 Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities CO-CHAIRS D. Kupfer (Germany, Fed. Rep.) R. Karimanzira (Zimbabwe) CONTENTS AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY, AND OTHER HUMAN ACTIVITIES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 77 4.1 INTRODUCTION 85 4.2 FOREST RESPONSE STRATEGIES 87 4.2.1 Special Issues on Boreal Forests 90 4.2.1.1 Introduction 90 4.2.1.2 Carbon Sinks of the Boreal Region 90 4.2.1.3 Consequences of Climate Change on Emissions 90 4.2.1.4 Possibilities to Refix Carbon Dioxide: A Case Study 91 4.2.1.5 Measures and Policy Options 91 4.2.1.5.1 Forest Protection 92 4.2.1.5.2 Forest Management 92 4.2.1.5.3 End Uses and Biomass Conversion 92 4.2.2 Special Issues on Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.1 Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.2 Global Warming: Impacts and Effects on Temperate Forests 93 4.2.2.3 Costs of Forestry Countermeasures 93 4.2.2.4 Constraints on Forestry Measures 94 4.2.3 Special Issues on Tropical Forests 94 4.2.3.1 Introduction to Tropical Deforestation and Climatic Concerns 94 4.2.3.2 Forest Carbon Pools and Forest Cover Statistics 94 4.2.3.3 Estimates of Current Rates of Forest Loss 94 4.2.3.4 Patterns and Causes of Deforestation 95 4.2.3.5 Estimates of Current Emissions from Forest Land Clearing 97 4.2.3.6 Estimates of Future Forest Loss and Emissions 98 4.2.3.7 Strategies to Reduce Emissions: Types of Response Options 99 4.2.3.8 Policy Options 103 75 76 IPCC RESPONSE STRATEGIES WORKING GROUP REPORTS 4.3 AGRICULTURE RESPONSE STRATEGIES 105 4.3.1 Summary of Agricultural Emissions of Greenhouse Gases 105 4.3.2 Measures and -

1 Environmental Implications of the American Forest and Paper Association's (AF&PA) Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) Pr

Environmental Implications of the American Forest and Paper Association's (AF&PA) Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) Program in Comparison with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) Program for Forest Certification. June 1999 Sustainable Forest Initiative While the American Forest and Paper Association's (AF&PA) Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) program may represent a start to make necessary improvements in US forest products industry practices, no leading environmental advocacy organizations currently endorse the program or any environmental claims arising from it. Despite SFI's tagline ("Showing the World a Higher Standard"), leading environmental groups are not convinced that the program is, in fact, showing the world an appreciably higher standard at this time. Exemplifying concern about environmental performance under SFI is the participation of The Pacific Lumber Company (Maxxam). Pacific Lumber formally complied with the requirements for SFI according to AF&PA’s annual progress reports for SFI in 1996, 1997, 1998 and 1999. Nonetheless, during this period, Pacific Lumber became well-known for its role in the Headwaters controversy over clearcutting ancient redwoods, and it had 128 citations and approximately 300 violations of the California state forest practices rules since 1995 which resulted in the suspension of its license to practice forestry in the state of California from November 1998 through early 1999. Obviously, the overall rigor of the SFI is called into serious question by such performance. By association, the performance of other AF&PA members is also called into question. The Sustainable Forestry Initiative has been developed and is administered by the American Forest and Paper Association for its members (approximately 200 companies and trade associations representing 56 million forested acres and 90% of US industrial timberlands). -

Blue Ridge Parkway DIRECTORY & TRAVEL PLANNER Includes the Parkway Milepost

Blue Ridge Park way DIRECTORY & TRAVEL PLANNER Includes The Parkway Milepost Shenandoah National Park / Skyline Drive, Virginia Luray Caverns Luray, VA Exit at Skyline Drive Milepost 31.5 The Natural Bridge of Virginia Natural Bridge, VA Exit at Milepost 63.9 Grandfather Mountain Linville, NC Exit at Milepost 305.1 2011 COVER chosen.indd 3 1/25/11 1:09:28 PM The North The 62nd Edition Carolina Arboretum, OFFICIAL PUBLICATION BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY ASSOCIATION, INC. Asheville, NC. P. O. BOX 2136, ASHEVILLE, NC 28802 Exit at (828) 670-1924 Milepost 393 COPYRIGHT 2011 NO Portion OF THIS GUIDE OR ITS MAPS may BE REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA. Some Parkway photographs by William A. Bake, Mike Booher, Vickie Dameron and Jeff Greenberg © Blue Ridge Parkway Association Layout/Design: Imagewerks Productions: Fletcher, NC This free Travel Directory is published by the 500+ PROMOTING member Blue Ridge Parkway Association to help you more TOURISM FOR fully enjoy your Parkway area vacation. Our member- MORE THAN ship includes attractions, outdoor recreation, accom- modations, restaurants, 60 YEARS shops, and a variety of other services essential to the trav- eler. All our members are included in this Travel Directory. Distribution of the Directory does not imply endorsement by the National Park Service of the busi- nesses or commercial services listed. When you visit their place of business, please let them know you found them in the Blue Ridge Parkway Travel Directory. This will help us ensure the availability of another Directory for you the next time you visit the Parkway area. -

Mainstreaming Native Species-Based Forest Restoration

93 ISBN 978-9962-614-22-7 Mainstreaming Native Species-Based Forest Restoration July 15-16, 2010 Philippines Sponsored by the Environmental Leadership & Training Initiative (ELTI), the Rain Forest Restoration Initiative (RFRI), and the Institute of Biology, University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman Conference Proceedings 91 Mainstreaming Native Species-Based Forest Restoration Conference Proceedings July 15-16, 2010 Philippines Sponsored by The Environmental Leadership & Training Initiative (ELTI) Rain Forest Restoration Initiative (RFRI) University of the Philippines (UP) 2 This is a publication of the Environmental Leadership & Training Initiative (ELTI), a joint program of the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES) and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI). www.elti.org Phone: (1) 203-432-8561 [US] E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Text and Editing: J. David Neidel, Hazel Consunji, Jonathan Labozzetta, Alicia Calle, Javier Mateo-Vega Layout: Alicia Calle Photographs: ELTI-Asia Photo Collection Suggested citation: Neidel, J.D., Consunji, H., Labozetta, J., Calle, A. and J. Mateo- Vega, eds. 2012. Mainstreaming Native Species-Based Forest Restoration. ELTI Conference Proceedings. New Haven, CT: Yale University; Panama City: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. ISBN 978-9962-614-22-7 3 Acknowledgements ELTI recognizes the generosity of the Arcadia Fund, whose fund- ing supports ELTI and helped make this event possible. Additional funding was provided by the Philippine Tropical Forest Conserva- tion Foundation. 4 List of Acronyms ANR Assisted Natural Regeneration Atty. Attorney CBFM Community-Based Forest Management CDM Clean Development Mechanism CI Conservation International CO2 Carbon Dioxide DENR Department of Environment & Natural Resources FAO United Nations Food & Agriculture Organization FMB Forest Management Bureau For. -

Principles and Practice of Forest Landscape Restoration Case Studies from the Drylands of Latin America Edited by A.C

Principles and Practice of Forest Landscape Restoration Case studies from the drylands of Latin America Edited by A.C. Newton and N. Tejedor About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting scientific research, managing field projects all over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,000 government and NGO members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in 60 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org Principles and Practice of Forest Landscape Restoration Case studies from the drylands of Latin America Principles and Practice of Forest Landscape Restoration Case studies from the drylands of Latin America Edited by A.C. Newton and N. Tejedor This book is dedicated to the memory of Margarito Sánchez Carrada, a student who worked on the research project described in these pages. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or the European Commission concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Blue Ridge Park Way DIRECTORY TRAVEL PLANNER

65 TH Edition Blue Ridge Park way www.blueridgeparkway.org DIRECTORY TRAVEL PLANNER Includes THE PARKWAY MILEPOST Biltmore Asheville, NC Exit at Milepost 388.8 Grandfather Mountain Linville, NC Exit at Milepost 305.1 Roanoke Star and Overlook Roanoke, VA Exit at Milepost 120 Official Publication of the Blue Ridge Parkway Association The 65th Edition OFFICIAL PUBLICATION BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY ASSOCIATION, INC. P. O. BOX 2136, ASHEVILLE, NC 28802 (828) 670-1924 www.blueridgeparkway.org • [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2014 NO Portion OF THIS GUIDE OR ITS MAPS may BE REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA. Some Parkway photographs by William A. Bake, Mike Booher, Vicki Dameron and Jeff Greenberg © Blue Ridge Parkway Association Layout/Design: Imagewerks Productions: Arden, NC This free Directory & Travel PROMOTING Planner is published by the 500+ member Blue Ridge TOURISM FOR Parkway Association to help Chimney Rock at you more fully enjoy your Chimney Rock State Park Parkway area vacation. MORE THAN Members representing attractions, outdoor recre- ation, accommodations, res- Follow us for more Blue Ridge Parkway 60 YEARS taurants, shops, and a variety of other services essential to information and resources: the traveler are included in this publication. When you visit their place of business, please let them know www.blueridgeparkway.org you found them in the Blue Ridge Parkway Directory & Travel Planner. This will help us ensure the availability of another Directory & Travel Planner for your next visit -

Shining Rock and Grassy Cove Top Hike

Old Butt Knob Trail and Shining Creek Trail Loop - Shining Rock Wilderness, Pisgah National Forest, NC Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 11.9 mls Hiking Time: 8 hours with 2 hours of breaks Elev. Gain: 3,410 ft Parking: Park at the Big East Fork Trailhead on U.S. 276. 35.36583, -82.81786 By Trail Contributor: Zach Robbins The Old Butt Knob Trail and Shining Creek Trail loop is a classic introduction to the Shining Rock Wilderness Area of North Carolina. Beginning at the Big East Fork Trailhead on U.S. 276, both trails climb from 3,384 feet to meet the Art Loeb Trail above 5,800 feet at Shining Rock Gap. Despite the relatively short length of this loop (9.4 miles including Shining Rock), this is a difficult day hike for hikers of all abilities. The Old Butt Knob Trail climbs over 1,400 feet in the first mile, and the Shining Creek Trail is incredibly rocky and steep over its last mile. Despite the hardship, this is an excellent backpacking loop with outstanding campsites and even better views. The Old Butt Knob Trail features multiple views from southern-facing rock outcrops, and the views from Shining Rock and Grassy Cove Top are some of the highlights of the wilderness. Even though this is a wilderness area, this is in close proximity to Asheville and is popular with weekend backpackers. Try to start early if you want to camp at Shining Rock Gap, which is one of the best campsites in the region and is also the crossroads for 4 trails within the wilderness.