Diagnosis and Management of Tachycardias After Myocardial Infarction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Types of Supraventricular Tachycardia: Diagnosis and Management RANDALL A

Common Types of Supraventricular Tachycardia: Diagnosis and Management RANDALL A. COLUCCI, DO, MPH, Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, Ohio MITCHELL J. SILVER, DO, McConnell Heart Hospital, Columbus, Ohio JAY SHUBROOK, DO, Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, Ohio The most common types of supraventricular tachycardia are caused by a reentry phenomenon producing acceler- ated heart rates. Symptoms may include palpitations (including possible pulsations in the neck), chest pain, fatigue, lightheadedness or dizziness, and dyspnea. It is unusual for supraventricular tachycardia to be caused by structurally abnormal hearts. Diagnosis is often delayed because of the misdiagnosis of anxiety or panic disorder. Patient history is important in uncovering the diagnosis, whereas the physical examination may or may not be helpful. A Holter moni- tor or an event recorder is usually needed to capture the arrhythmia and confirm a diagnosis. Treatment consists of short-term or as-needed pharmacotherapy using calcium channel or beta blockers when vagal maneuvers fail to halt or slow the rhythm. In those who require long-term pharmacotherapy, atrioventricular nodal blocking agents or class Ic or III antiarrhythmics can be used; however, these agents should generally be managed by a cardiologist. Catheter ablation is an option in patients with persistent or recurrent supraventricular tachycardia who are unable to tolerate long-term pharmacologic treatment. If Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is present, expedient referral -

Original Article Reversibility of Both Sinus Node Dysfunction and Reduced HCN4 Mrna Expression Level in an Atrial Tachycardia

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2016;9(8):8526-8531 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0023042 Original Article Reversibility of both sinus node dysfunction and reduced HCN4 mRNA expression level in an atrial tachycardia pacing model of tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome in rabbit hearts Zhisong Chen1*, Bing Sun1*, Gary Tse2, Jinfa Jiang1, Wenjun Xu1 1Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Tongji Hospital of Tongji University, Shanghai, P. R. China; 2School of Biomedical Sciences, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, P. R. China. *Equal contributors. Received December 31, 2015; Accepted March 17, 2016; Epub August 1, 2016; Published August 15, 2016 Abstract: Objective: The aim of this study was to investigate potential reversible changes in sinus node function and mRNA expression levels of hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel subunit 4 (HCN4) in a tachycardia pacing model in rabbits. Methods: A total of 45 adult New Zealand white rabbits were randomized into the following three groups (n=15): pacing only, pacing-recovery and control. Following open thoracotomy, temporary pacing leads were attached to the right atrium. In the pacing only group, rapid atrial pacing was initiated at a rate of 350 stimuli per minute for 8 hours a day, continuing for 7 days. In the pacing-recovery group, the same pacing protocol was delivered, but pacing was then stopped for 7 days. In the control group, no tachycardia pacing was de- livered. The following parameters were measured before and after intervention, and compared between the groups: resting heart rate, intrinsic heart rate (measured after metoprolol and atropine administration) and corrected sinus node recovery time (CSNRT). -

Aberrated Supraventricular Tachycardia Associated with Neonatal Fever and COVID-19 Infection Kali a Hopkins ,1 Gregory Webster2

Case report BMJ Case Rep: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2021-241846 on 30 April 2021. Downloaded from Aberrated supraventricular tachycardia associated with neonatal fever and COVID-19 infection Kali A Hopkins ,1 Gregory Webster2 1Department of Paediatrics, SUMMARY Her blood pressure was 87/63 mm Hg and her Northwestern University A 9-day- old girl presented during the 2020 SARS- peripheral oxygen saturation was 97%. Her lungs Feinberg School of Medicine, CoV-2 pandemic in wide-complex tachycardia with were clear to auscultation. She had no murmur or Chicago, Illinois, USA acute, symptomatic COVID-19 infection. Because the hepatosplenomegaly, and her capillary refill was 2 s. 2Division of Cardiology, Ann potential cardiac complications of COVID-19 were Three- lead telemetry revealed a regular, WCT. Her and Robert H Lurie Children’s mother, the primary caregiver, was acutely symp- Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, unknown at the time of her presentation, we chose Illinois, USA to avoid the potential risks of haemodynamic collapse tomatic with suspected COVID-19 illness (later associated with afterload reduction from adenosine. verified by PCR) and other household contacts Correspondence to Instead, a transoesophageal pacing catheter was placed. were COVID-19 positive. The infant had no family Dr Kali A Hopkins; Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with an aberrated history of sudden death or rhythm disorders. kahopkins@ luriechildrens. org QRS morphology was diagnosed and the catheter was used to pace-terminate tachycardia. This presentation INVESTIGATIONS Accepted 18 April 2021 illustrates that the haemodynamic consequences of a The initial 12- lead ECG recorded regular tachy- concurrent infection with largely unknown neonatal cardia at 215 beats per minute (figure 1). -

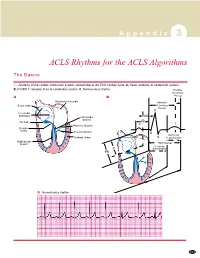

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

Dysrhythmias

CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS DYSRHYTHMIAS I. BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CARDIAC CONDUCTION DISTURBANCES A. Standard ECG and rhythm strips 1. Recordings are obtained at a paper speed of 25 mm/sec. 2. The vertical axis measures distance; the smallest divisions are 1 mm ×1 mm. 3. The horizontal axis measures time; each small division is 0.04 sec/mm. B. Normal morphology Courtesy of Dr. Michael McCrea 1. P wave = atrial depolarization a. Upright in leads I, II, III, aVL, and aVF; inverted in lead aVR b. Measures <0.10 seconds wide and <3 mm high c. Normal PR interval is 0.12–0.20 seconds. 2. QRS complex = ventricular depolarization a. Measures 0.06-0.10 seconds wide b. Q wave (1) <0.04 seconds wide and <3 mm deep (2) Abnormal if it is >3 mm deep or >1/3 of the QRS complex. c. R wave ≤7.5 mm high 3. QT interval varies with rate and sex but is usually 0.33–0.42 seconds; at normal heart rates, it is normally <1/2 the preceding RR interval. 4. T wave = ventricular repolarization a. Upright in leads I, II, V3–V6; inverted in aVR b. Slightly rounded and asymmetric in configuration c. Measures ≤5 mm high in limb leads and ≤10 mm high in the chest leads 5. U wave = a ventricular afterpotential a. Any deflection after the T wave (usually low voltage) b. Same polarity as the T wave c. Most easily detected in lead V3 d. Can be a normal component of the ECG e. Prominent U waves may indicate one of the following: (1) Hypokalemia (<3 mEq/L) (2) Hypercalcemia (3) Therapy with digitalis, phenothiazines, quinidine, epinephrine, inotropic agents, or amiodarone (4) Thyrotoxicosis f. -

The Bradycardia-Tachycardia Syndrome Treatment with Cardiac Drugs and Adrenal Corticosteroid Junichi FUJII, M.D., Nobumitsu TAKA

The Bradycardia-Tachycardia Syndrome Treatment with Cardiac Drugs and Adrenal Corticosteroid Junichi FUJII, M.D., Nobumitsu TAKAHASHI,M.D., and Kazuzo KATO, M.D. Seven patients of S-A block complicated by tachycardic paroxysms of atrial fibrillation or flutter were described and the medical treatment in this syndrome was reappraised. Damage to S-A node and adjacent atrial tissue was assumed in all patients. All the patients had syncopal attacks associated with cardiac arrest occurring especially at the termina- tion of tachycardia. Overdrive suppression of diseased S-A node and lower automatic pacemakers was demonstrated by ECG recordings. The term "bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome" or "syndrome of alternating bradycardia and tachycardia" seemed appropriate. In spite of difficulty of medical treatment reiterated by previous de- scriptions, 6 of 7 patients were improved with drug therapy, including adrenal corticosteroid. Adrenal corticosteroid in combination with or- ciprenaline or belladonna alkaloids was most helpful among the drugs used. Obviously, pacemaker implantation should be performed without delay in patients with frequent and prolonged attacks of syncope. But not all patients have need of pacemaker implantation. A trial of drug therapy may be permitted in many patients of this syndrome before in- troduction of pacemaker. Additional Indexing Words: Sick sinus syndrome S-A block Atrial tachyarrhythmias Syn- cope Overdrive suppression ECENTLY there have been some reports concerning the patients with S-A block or sinus bradycardia accompanied by paroxysmal atrial tachy- arrhythmias such as fibrillation, flutter and paroxysmal tachycardia. As pointed out by several authors, these patients repeatedly exhibited syncopal attacks associated with asystole following termination of the tachycardia. -

90 Correlation of Cardiac Hemodynamics and Bioenergetics Using Phosphorus Nmrspectroscopy

CARDIOLOGY 125A DETECTION OF ATRIOVENTRICULAR VALVE ABNORMALITIES FUNCTIONAL THYROTOXIC CARDIOMYOPATHY IN CHILDREN. BY ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY IN CHROMOSOMAL ANOMALIES Anita Cavallo, Alfonso Casta, H. Daniel Fawcett, 85 Alfonso Casta, Karen Haslund, Kirk Aleck, Janet Martin L. Nusynowitz, and Wendy J. Wolf (Spon. by Williams, Chalermlarp Mongkalsmai, Amarjit Singh, Walter J. Meyer), Departments of Pediatrics and Radiology, uni (Span. by Ben Brouhard) U.ni v. of Texas, Ga 1 veston, Southern versity of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas. Illinois Univ., Springfield, Minneapolis Children's Health Myocardial performance during thyrotoxicosis (T) was evalu Center tted by multigated radionuc lide angiocardiography during graded Cardiac malformations are not uncommon in chromosomal anoma =xercise in 8 children (8-17 ys) with Graves' disease. With lies and may contribute to early death. In this study, two exercise, heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) in dimensional echocardiography demonstrated unusual atrioventric creased in all patients; left ventricular ejection fraction ular valve abnormalities in 4 neonates without overt structural (LVEF) increased normally by 7 to 10% in 4 (2 male, 2 female), heart defects (except for 1) and chromosomal anomalies. Three but did not increase significantly in 1 (male) and decreased by of 4 presented with signs of congestive heart failure: one had 3 to 8% in 3 (female) . There was no s ignificant difference in partial trisomy llp, redundant mitral and tricuspid valves the duration of T, resting and exercise HR and SBP, or resting and an aneurysm of the interatrial septum; one had Teschler/ LVEF, between patients with normal and abnormal responses . The Nicola-Killian syndrome, a redundant mitral valve and a small change in LVEF was inversely correlated with serum T4 (r= -.82, atrial septal defect; and one had trisomy 18, a large ventric p<.02) and T3 (r= -.88, p<.OS). -

2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial fibrillation

2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation Hugh Calkins, MD (Chair),1 Gerhard Hindricks, MD (Vice-Chair),2,* Riccardo Cappato, MD (Vice-Chair),3,{ Young-Hoon Kim, MD, PhD (Vice-Chair),4,x Eduardo B. Saad, MD, PhD (Vice-Chair),5,z Luis Aguinaga, MD, PhD,6,z Joseph G. Akar, MD, PhD,7 Vinay Badhwar, MD,8,# Josep Brugada, MD, PhD,9,* John Camm, MD,10,* Peng-Sheng Chen, MD,11 Shih-Ann Chen, MD,12,x Mina K. Chung, MD,13 Jens Cosedis Nielsen, DMSc, PhD,14,* Anne B. Curtis, MD,15,k D. Wyn Davies, MD,16,{ John D. Day, MD,17 André d’Avila, MD, PhD,18,zz N.M.S. (Natasja) de Groot, MD, PhD,19,* Luigi Di Biase, MD, PhD,20,* Mattias Duytschaever, MD, PhD,21,* James R. Edgerton, MD,22,# Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD,23 Patrick T. Ellinor, MD, PhD,24 Sabine Ernst, MD, PhD,25,* Guilherme Fenelon, MD, PhD,26,z Edward P. Gerstenfeld, MS, MD,27 David E. Haines, MD,28 Michel Haissaguerre, MD,29,* Robert H. Helm, MD,30 Elaine Hylek, MD, MPH,31 Warren M. Jackman, MD,32 Jose Jalife, MD,33 Jonathan M. Kalman, MBBS, PhD,34,x Josef Kautzner, MD, PhD,35,* Hans Kottkamp, MD,36,* Karl Heinz Kuck, MD, PhD,37,* Koichiro Kumagai, MD, PhD,38,x Richard Lee, MD, MBA,39,# Thorsten Lewalter, MD, PhD,40,{ Bruce D. Lindsay, MD,41 Laurent Macle, MD,42,** Moussa Mansour, MD,43 Francis E. Marchlinski, MD,44 Gregory F. -

Banner Staff Service ECG Study Guide

Banner Staff Service ECG Study Guide Edited by Larry H. Lybbert, MS, RN Table of Contents ECG STUDY GUIDE ................................................................................................................................................... 3 ECG INTERPRETATION BASICS........................................................................................................................... 4 EKG GRAPH PAPER ..................................................................................................................................................4 RATE MEASUREMENT...............................................................................................................................................9 The Six Second Method........................................................................................................................................9 Large Box Method................................................................................................................................................9 Small Box Method ................................................................................................................................................9 BASIC EKG RHYTHM ANALYSIS GUIDE ................................................................................................................11 Rhythm Interpretation........................................................................................................................................13 Six Basic Steps for Rhythm Interpretation -

Tachycardia Related Cardiomyopathy: Response to Control of the Arrhythmia

Tachycardia Related Cardiomyopathy: Response to Control of the Arrhythmia BURT I. BROMBERG, M.D., MACDONALD DICK 11, M.D., A. REBECCA SNIDER, M.D., WILLIAM A. SCOTT, M.D., GERALD A. SERWER, M.D., EDWARD L. BOVE, M.D., and KATHLEEN P. HEIDELBERGER, M.D. From the Division of Pediatric Cardiology, C. S. Mott Children S Hospital, and the Departments of Pediatrics, Surgery, and Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan To evaluate the clinical response of five children ingfraction (20% pre vs 34% post; P = 0.006), with automatic atrial tachycardia (AA T) and as- mean ejection fraction (36% pre vs 50% post; P sociated cardiomyopathy to arrhythmia control, < 0.01), mean velocity of’ circumferential fiber we compared pretreatment and posttreatment 24- shortening (0.62 pre vs 1.20 post; P = 0.003). hour ECG heart rates, cardiothoracic ratio by Mean E-point septa1 separation corrected for end- chest radiograph, and echocardiographic mea- diastolic dimension also showed a trend toward sures of ventricular ,function. Two children were improvement (0.25 pre vs 0.16 post; P = 0.11). treated with amiodarone, two with surgical exci- Right ventricular endocardial biopsies in four were sion and cryoablation of the ectopicfocus, and one nonspecific; an atrial biopsy from surgery showed with digoxin alone. Signijicantly slower mean a Purkinje fiber-like tissue in one patient, but was heart rates were achieved, along with a dominant nonspecijic in another. We conclude that cardio- sinus rhythm and improvement in symptoms. myopathy can be causally linked to automatic Control of the AAT resulted in improved mean atrial tachycardia and that aggressive medical cardiothoracic ratio (0.53 pre vs 0.49 post; P and/or surgical management is warranted in those = 0.021, as well as improvement in a number of patients with signs and symptoms of impaired ven- echocardiographic measurements: mean shorten- tricular function. -

Management of Atrial Tachycardia in the Newborn with Enterovirus Myocarditis

The Ochsner Journal 12:163–166, 2012 Ó Academic Division of Ochsner Clinic Foundation Management of Atrial Tachycardia in the Newborn With Enterovirus Myocarditis Daniel H. Petroni, MS,* Song G. Yang, MD, PhD,* Mudar M. Kattash, MD,* Christopher S. Snyder, MD* *Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Ochsner Clinic Foundation, New Orleans, LA meningoencephalitis, myocarditis, and hepatitis.2 In ABSTRACT addition, infants younger than 10 days are unable to Neonatal enterovirus myocarditis is a rare but serious infection mount a significant immune response and are at a that is often an underrecognized cause of cardiovascular higher risk of a serious infection from these nonpolio collapse. Enterovirus myocarditis in patients with such EVs.2 collapse should be suspected when signs of congestive heart Clinical manifestations of EV myocarditis in neo- failure and tachyarrhythmia are present. The majority of nates may include signs of congestive heart failure reported electrical disturbances associated with enterovirus and tachycardia. The mechanism of EV-induced myocarditis are ventricular in origin, but the infection can damage to cardiac myocytes is unknown, but it has present as atrial tachyarrhythmia. Atrial tachyarrhythmias been suggested that the mechanism is through a associated with enterovirus myocarditis are difficult to manage direct viral-mediated cytotoxicity as well as damage because of their resistance to conventional antiarrhythmic from the body’s own immune response.3 Abnormal- therapy. We present 2 cases of neonates with atrial ities most commonly seen on electrocardiogram tachycardia associated with enterovirus myocarditis who (EKG) in patients with EV myocarditis include sinus responded to a combination of amiodarone and flecainide. -

Supraventricular Arrhythmias.Pdf

general: - SVTs are any tachycardia that require atrial - sometimes called ectopic atrial tachycardia or AV nodal tissue for their initiation & maintenance - SVTs are usually narrow complexes but may be wide complex in ecg: the setting of bundle branch block or pre-excitation - p wave morphology is often abnormal but monomorphic atrial rate is often 130-160bpm and may exceed 200bpm - in critical illness the continuing arrhythmogenic and chronotropic factors make - AV block is common rate control of SVTs difficult general - digoxin often results in poor rate control in critical illness (although it may have clinical: unifocal minor inotropic and vasopressor effects that are beneficial) - digoxin toxicity is the most common cause especially when AV block is present atrial - magnesium provides effective rate control and may revert SVT - other causes include myocardial infarction, chronic lung disease & metabolic disturbance tachycardia - amiodarone may be useful for rate control treatment: - cardioversion is indicated in unstable patients but is more likely to maintain SR - if applicable digoxin is stopped and toxicity is treated; if loading with an anti-arrhythmic such as amiodarone has been performed prior otherwise it may be used to control ventricular rate - blockers or amiodarone are alternatives - overdrive pacing may be ineffective but may slow ventricular rate by increasing AV block AV node dependent (junctional tachycardias): - synchronised cardioversion may be required but should be avoided with digoxin toxicity (i) AV nodal re-entrant