Compositional Strategies in the Music of Hans Abrahamsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klsp2018iema Broschuere.Indd

KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY IN TIROL. REBECCA SAUNDERS COMPOSER IN RESIDENCE. 15TH EDITION 29.08. – 09.09.2018 KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY 2018 KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ is celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2018. The annual Tyrolean festival of contemporary music provides a stage for performances, encounters, and for the exploration and exchange of new musical ideas. With a different thematic focus each year, KLANGSPUREN aims to present a survey of the fascinating, diverse panorama that the music of our time boasts. KLANGSPUREN values open discourse, participation, and partnership and actively seeks encounters with locals as well as visitors from abroad. The entire beautiful region of Tyrol unfolds as the festival’s playground, where the most cutting-edge and modern forms of music as well as many young composers and musicians are presented. On the occasion of its own milestone anniversary – among other anniversaries that KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ 2018 will be celebrating this year – the 25th edition of the festival has chosen the motto „Festivities. Places.“ (in German: „Feste. Orte.“). The program emphasizes projects and works that focus on aspects of celebrations, festivities, rituals, and events and have a specific reference to place and situation. KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The Academy is an offshoot of the renowned International Ensemble Modern Academy (IEMA) in Frankfurt and was founded in the same year as IEMA, in 2003. The Academy is central to KLANGSPUREN and has developed into one of the most successful projects of the Tyrolean festival for new music. The high standards of the Academy are vouched for by prominent figures who have acted as Composers in Residence: György Kurtág, Helmut Lachenmann, Steve Reich, Benedict Mason, Michael Gielen, Wolfgang Rihm, Martin Matalon, Johannes Maria Staud, Heinz Holliger, George Benjamin, Unsuk Chin, Hans Zender, Hans Abrahamsen, Wolfgang Mitterer, Beat Furrer, Enno Poppe, and most recently in 2017, Sofia Gubaidulina. -

Roots & Origins

Sunday 16 December 2018 7–9.15pm Tuesday 18 December 2018 7.30–9.45pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT ROOTS & ORIGINS Brahms Violin Concerto Interval ROMANIAN Debussy Images Enescu Romanian Rhapsody No 1 Sir Simon Rattle conductor Leonidas Kavakos violin These performances of Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsody No 1 are generously RHAPSODY supported by the Romanian Cultural Institute 16 December generously supported by LSO Friends Welcome Latest News On Our Blog We are grateful to the Romanian Cultural BRITISH COMPOSER AWARDS MARIN ALSOP ON LEONARD Institute for their generous support of these BERNSTEIN’S CANDIDE concerts. Sunday’s concert is also supported Congratulations to LSO Soundhub Associate by LSO Friends, and we are delighted to have Liam Taylor-West and LSO Panufnik Composer Marin Alsop conducted Bernstein’s Candide, so many Friends with us in the audience. Cassie Kinoshi for their success in the 2018 with the LSO earlier this month. Having We extend our thanks for their loyal and British Composer Awards. Prizes were worked closely with the composer across important support of the LSO, and their awarded to Liam for his Community Project her career, Marin drew on her unique insight presence at all our concerts. The Umbrella and to Cassie for Afronaut, into Bernstein’s music, words and sense of a jazz composition for large ensemble. theatre to tell us about the production. I wish you a very happy Christmas, and hope you can join us again in the New Year. The • lso.co.uk/more/blog elcome to this evening’s LSO LSO’s 2018/19 concert season at the Barbican FELIX MILDENBERGER JOINS THE LSO concert at the Barbican. -

Wuorinen Printable Program

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Celebrating Charles Wuorinen at 80 featuring Ensemble SIGNAL Brad Lubman, conductor Tuesday, April 24, 2018 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Charles Wuorinen (b. 1938) iRidule Jacqueline Leclair, oboe soloist Spin 5 Olivia De Prato, violin soloist Intermission Megalith Eric Huebner, piano soloist PERSONNEL Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, Music Director Paul Coleman, Sound Director Olivia De Prato, Violin Lauren Radnofsky, Cello Ken Thomson, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet Adrián Sandí, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet David Friend, Piano 1 Oliver Hagen, Piano 2 Karl Larson, Piano 3 Georgia Mills, Piano 4 Matt Evans, Vibraphone, Piano Carson Moody, Marimba 1 Bill Solomon, Marimba 2 Amy Garapic, Marimba 3 Brad Lubman, Marimba Sarah Brailey, Voice 1 Mellissa Hughes, Voice 2 Kirsten Sollek, Voice 4 Charles Wuorinen In 1970 Wuorinen became the youngest composer at that time to win the Pulitzer Prize (for the electronic work Time's Encomium). The Pulitzer and the MacArthur Fellowship are just two among many awards, fellowships and other honors to have come his way. Wuorinen has written more than 260 compositions to date. His most recent works include Sudden Changes for Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Exsultet (Praeconium Paschale) for Francisco Núñez and the Young People's Chorus of New York, a String Trio for the Goeyvaerts String Trio, and a duo for viola and percussion, Xenolith, for Lois Martin and Michael Truesdell. The premiere of of his opera on Annie Proulx's Brokeback Mountain was was a major cultural event worldwide. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Les Nuits D'été

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Les nuits d’été «El llum et fa de sol i colra les pells tendres i madura les carns de les fruites que guardes.» Narcís Comadira Natura morta Programa Palau 100 DIMARTS 06.03.18 – 20.30 h Sala de Concerts London Symphony Orchestra Ann Hallenberg, mezzosoprano Sir John Eliot Gardiner, director I Part Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Obertura, scherzo i finale, op. 52 18’ Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) Les nuits d’été, op. 7 30’ Villanelle Le spectre de la rose Sur les lagunes: lamento Absence Au cimetière: clair de lune L’île inconnue II Part Robert Schumann Obertura de Genoveva, op. 81 10’ Robert Schumann Simfonia núm. 4, op. 120 (versió original de 1841) 24’ Andante con moto - Allegro di molto Romanza: Andante Scherzo: Presto Largo - Finale: Allegro vivace a l’octubre. Poc després de començar a esbossar- l’agost del 1850. De fet, les dues òperes van Schumann i Berlioz, lo, Schumann va assenyalar: “la propera simfonia sorgir en paral·lel durant el mateix període de es titularà «Clara» i la pintaré amb flautes, oboès temps. De Genoveva, només se’n varen fer tres i arpes”. De totes formes, seria un error buscar representacions. L’actitud adversa de la crítica romanticisme pur vestigis tangibles d’aquest retrat, o tractar de va fer desistir Robert Schumann de repetir mai detectar el nom de Clara amagat al teixit temàtic més una nova experiència operística. D’altra de la Simfonia, com han fet alguns crítics. La banda, Genoveva mai no ha estat popular entre primavera del 1841, tot allò que mirava o el públic, malgrat que, de tant en tant, s’ha escoltava el compositor, acabava associat a la recuperat i fins i tot enregistrat. -

06 20 PROGRAM FULL PAGE.Pdf

About the festival The New Music For Strings Festival (NMFS) is delighted to announce the launch of its second annual season from June 21 to July 1, 2017. Hosted by Stony Brook University in 2017, NMFS brings together performers and composers of contemporary classical music from across the Atlantic. NMFS showcases a roster of world-class musicians, ranging from members of the Grammy Award- winning Emerson String Quartet to faculty from Stony Brook University (NY) and Royal Academy of Music in Aarhus, Denmark. Resident faculty and artists of NMFS 2017 will be showcased alongside accomplished student participants that include graduate students from top conservatories and universities in the U.S. and Europe. The 10-day festival features fourteen events—including six concerts, three masterclasses, five lectures and a composition pre-festival workshop for high-school students. The season will culminate with a tour de force festival performance at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall, which will highlight the full roster of 27 festival artists from America and Scandinavia. As the first festival concept of its kind in the world, NMFS seeks to explore the intersections between string playing and composition. NMFS boasts an elite artist faculty for participants to work with, many of whom have established themselves as leaders in their field in the dual role of performer-composer. By highlighting this intersectional perspective throughout the festival, NMFS offers a variety of lectures, masterclasses and concerts on the dynamic interactions between these two intertwined fields of creation and interpretation. Music has the power of bridging cultures and enlightening minds. NMFS is dedicated to sustaining and enriching the vibrant classical music community in Long Island. -

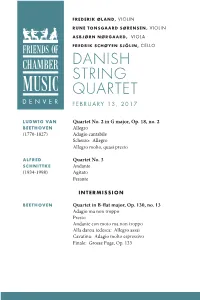

Danish String Quartet Denver February 13, 2017

FREDERIK ØLAND, VIOLIN RUNE TONSGAARD SØRENSEN, VIOLIN ASBJØRN NØRGAARD, VIOLA FREDRIK SCHØYEN SJÖLIN, CELLO DANISH STRING QUARTET DENVER FEBRUARY 13, 2017 LUDWIG VAN Quartet No. 2 in G major, Op. 18, no. 2 BEETHOVEN Allegro (1770-1827) Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Allegro molto, quasi presto ALFRED Quartet No. 3 SCHNITTKE Andante (1934-1998) Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION BEETHOVEN Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, no. 13 Adagio ma non troppo Presto Andante con moto ma non troppo Alla danza tedesca: Allegro assai Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 FREDERIK ØLAND DANISH STRING QUARTET violin RUNE TONSGAARD Embodying the quintessential elements of a fine chamber SØRENSEN music ensemble, the Danish String Quartet has established violin a reputation for their integrated sound, impeccable ASBJØRN NØRGAARD intonation, and judicious balance. Since making their debut viola in 2002 at the Copenhagen Festival, the musical friends have demonstrated a passion for Scandinavian composers, FREDRIK SCHØYEN who they frequently incorporate into adventurous SJÖLIN contemporary programs, while also giving skilled and cello profound interpretations of the classical masters. The New York Times selected the quartet’s concerts as highlights of the season during their Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Two Residency, and in February 2016 they received the Borletti Buitoni Trust provided to support outstanding young artists in their international endeavors, joining an illustrious roster of past recipients. The Danish String Quartet’s 2016-2017 season includes debuts at the Edinburgh Festival and Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall. In addition to over thirty North American engagements, the quartet’s robust international schedule takes them to their home country, Denmark, as well as throughout Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, Poland, Israel, as well as Argentina, Peru, and Colombia. -

The Guardian's Best Classical Music Works of the 21St Century

04/05/2020 The best classical music works of the 21st century | Music | The Guardian The best classical music works of the 1st century Over the coming week, the Guardian will select the greatest culture since 2000, carefully compiled by critics and editors. We begin with a countdown of defining classical music compositions, from Xrated opera to hightech string quartets • Read an interview with our No1 choice by Andrew Clements, Fiona Maddocks. John Lewis, Kate Molleson, Tom Service, Erica Jeal and Tim Ashley Main image: From left: The Tempest, The Minotaur, L’amour de loin, Hamlet Thu 12 Sep 2019 17.20 BST 25 Jennifer Walshe XXX Live Nude Girls 2003 Jennifer Walshe asked girls about how they played with their Barbie dolls, and turned the confessionals into an opera of horrors in which the toys unleash dark sex play and acts of mutilation. Walshe is a whiz for this kind of thing: she yanks off the plastic veneer of commercial culture by parodying then systematically dismembering the archetypes. KM Read our review | watch a production from 2016 BIFEM 24 John Adams City Noir 2009 Adams’s vivid portrait of Los Angeles, as depicted in the film noir of the 1940s and 50s, is a three-movement symphony of sorts, and a concerto for orchestra, too. It’s an in-your-face celebration of orchestral virtuosity that references a host of American idioms without ever getting too specific. It’s not his finest orchestral work by any means (those came last century), but an effective, extrovert showpiece. AC Read our review | Listen on Spotify https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/sep/12/best-classical-music-works-of-the-21st-century 1/10 04/05/2020 The best classical music works of the 21st century | Music | The Guardian Immediate … the Sixteen and Britten Sinfonia perform Stabat Mater, conducted by Harry Christophers. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Fall 2018 Whole Notes

Fall 2018 WholeThe magazine for friends and alumni of the UniversityNotes of Washington School of Music IN THIS ISSUE School 2 . School News News 4 . Zakir Hussain From the Director 5 . IMPFest X Stays True to Form This issue of Whole Notes PROFESSOR PATRICIA CAMPBELL JOINS ASSOCIATION FOR 7 . 20 Questions with Larry Starr highlights only a few of the 9 . Faculty News triumphs and achievements CULTURAL EQUITY BOARD 10 . Passages of our students and faculty School of Music Professor Patricia Campbell has joined the board of the Association for in the 2017-18 academic year. Cultural Equity (ACE), accepting an invitation extended by Anna Lomax Wood, anthropologist 11 . New Publications and Recordings It also pays tribute to the and daughter of musicologist Alan Lomax. 12 . New Faculty friends whose support creates “ACE is the archive (recordings and films) of Alan Lomax, John Lomax (father), and Bess 13 . Q&A with Huck Hodge opportunities for learning and Lomax Hawes (sister) that encompasses historic recordings from about 1915 to the late 15 . Ted Poor: The Blues & Otherwise discovery at the University of 1990s, a goldmine of recordings that are highly valued by musicologists, ethnomusicologists, 17 . Making Appearances Washington School of Music. folklorists, historians, and Americanists of every sort,” Campbell says. As a member of the 19 . Faculty Profile: Cristina Valdés ACE board, Campbell expects to help with the development of teaching and learning projects In this issue we shine a spotlight related to the historical study of American music, a role for which she is abundantly qualified. 21 . Charles Corey, Partch Master General on a few of our outstanding “I’ve been involved for over a decade in developing resources for teaching/learning (as have 23 . -

HANNIGA Sunday 17 March 2019

Sunday 17 March 2019 7–9.10pm Barbican LSO SEASON CONCERT BARBARA HANNIGAN Ligeti Concert Românesc Haydn Symphony No 86 HANNIGA Interval Berg Lulu – Suite Gershwin arr Hannigan & Elliott Girl Crazy – Suite Barbara Hannigan conductor/soprano Welcome Latest News To create the high-spirited Girl Crazy Suite, THE LSO’S 2019/20 SEASON CULTURE MILE COMMUNITY DAY Barbara Hannigan collaborated with Tony Award-winning composer and arranger The LSO’s 2019/20 season is now on sale. On Sunday 17 February, LSO St Luke’s Bill Elliott. The Suite uses the same Sir Simon Rattle continues his exploration was taken over for a day of performances, orchestration as Berg’s Lulu and brings of the roots and origins of music, including a workshops, music, food and crafts, run by together four numbers by George Gershwin, look back to the influence of Beethoven in Culture Mile to celebrate the irrepressible who was a friend of Berg’s in Vienna and the composer’s 250th anniversary year and creativity and community spirit of East who died only a month after Lulu’s premiere. a focus on how folk music inspired Bartók London. Join us for free at the next and Percy Grainger. François-Xavier Roth Community Day on 21 July. I hope you enjoy the concert and that you conducts complementary programmes of will join us again soon. At the end of the Bartók and Stravinsky, while Gianandrea • lso.co.uk/news elcome to tonight’s LSO concert at month the LSO is joined by soprano Diana Noseda continues his survey of Russian the Barbican, as Barbara Hannigan Damrau, singing Strauss and Iain Bell’s song works. -

Ntr Zaterdagmatinee NTRZM 2021-2022 Inhoud

DAM HET CONCERTGEBOUW AMSTER CONCERTGEBOUW HET NTR ZATERDAGMATINEE NTRZM 2021-2022 Inhoud 2 De onverwoestbare magie van de NTR ZaterdagMatinee KEES VLAARDINGERBROEK Uw donaties 4 NTR ZaterdagMatinee op Radio 4 en internet Gedurende de eerste lockdown vanwege het 5 Ongezien, maar niet ongehoord! dreigende coronavirus, nu ruim een jaar geleden, SIMONE MEIJER - ROLAND KIEFT hebben we tien Matineeconcerten moeten afgelasten. Een overweldigend aantal van onze 6 Hans Abrahamsen BAS VAN PUTTEN vaste bezoekers heeft toen het aankoopbedrag van de kaarten voor deze concerten omgezet in 10 The hidden soul of harmony WILLEM BRULS een donatie aan de serie. 6 13 Première-partituren JOEP CHRISTENHUSZ Deze donaties zijn volledig en uitsluitend ten 17 Nieuwe muziek in oude vaten SOFIE TAES goede gekomen aan de NTR ZaterdagMatinee. Wij zijn heel blij dat wij de musici wier concerten zijn afgezegd hiervoor (ten dele) hebben kunnen De series compenseren. Daarnaast hebben we een bedrag gereserveerd voor een aantal grote 19 Opera 6 concerten compositieopdrachten aan Nederlandse componisten. 29 RFO & Friends I 6 concerten RFO & Friends II 6 concerten Namens het team van de NTR ZaterdagMatinee 10 37 en alle musici en componisten: heel hartelijk GOK & Friends 4 concerten bedankt voor uw genereuze bijdrage! 45 51 Oude Muziek 5 concerten Kees Vlaardingerbroek Artistiek leider 59 Hedendaags 4 concerten 64 Een cultureel baken in onzekere tijden PAUL JANSSEN 13 68 Ons Radio Filharmonisch Orkest en VERKOOP ABONNEMENTEN INFORMATIE OVER DE PROGRAMMERING Groot Omroepkoor -

Juilliard AXIOM Program 02-02

AXIOM ii Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu iii The Juilliard School presents AXIOM Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Friday, February 2, 2018, 7:30 Peter Jay Sharp Theater HANS Schnee, Ten Canons for Nine Instruments (2006–08) ABRAHAMSEN Canon 1a (b. 1952) Ruhig aber beweglich Canon 1b Fast immer zart und still Canon 2 Lustig spielend, aber nicht zu lustig, immer ein bisschen melancholisch Intermezzo 1 Canon 2b Lustig spielend, aber nicht zu lustig, immer ein bisschen melancholisch Canon 3a Ser langsam, schleppend und mit Trübsinn (im Tempo des “Tai Chi”) Canon 3b Ser langsam, schleppend und mit Trübsinn (im Tempo des “Tai Chi”) Intermezzo 2 (Program continues) Support for this performance is provided, in part, by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium.