De-Constitutionalization and Majority Rule: a Democratic Vision for Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SINGLE-MEMBER PLURALITY and MIXED-MEMBER PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS : Different Concepts of an Election

THE SINGLE-MEMBER PLURALITY AND MIXED-MEMBER PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS : Different Concepts of an Election by James C. Anderson A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © James C. Anderson 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-23700-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-23700-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2005 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adrian Vermeule, "Absolute Voting Rules" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 257, 2005). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 257 (2D SERIES) Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=791724 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule* The theory of voting rules developed in law, political science, and economics typically compares simple majority rule with alternatives, such as various types of supermajority rules1 and submajority rules.2 There is another critical dimension to these questions, however. Consider the following puzzles: $ In the United States Congress, the votes of a majority of those present and voting are necessary to approve a law.3 In the legislatures of California and Minnesota,4 however, the votes of a majority of all elected members are required. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

1 European Demoicracy and Its Crisis1 KALYPSO NICOLAÏDIS

In Journal of Common Market Studies, March 2013, Vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 000-000. European Demoicracy and Its Crisis1 KALYPSO NICOLAÏDIS Abstract This article offers an overview and reconsideration of the idea of European demoicracy in the context of the current crisis. It defines demoicracy as ‘a Union of peoples, understood both as states and as citizens, who govern together but not as one,’ and argues that the concept is best understood as a third way, distinct from both national and supranational versions of single demos polities. The concept of demoicracy can serve both as an analytical lens for the EU-as-is and as a normative benchmark, but one which cannot simply be inferred from its praxis. Instead, the article deploys a ‘normative-inductive’ approach according to which the EU’s normative core - transnational non-domination and transnational mutual recognition - is grounded on what the EU still seeks to escape. Such norms need to be protected and perfected if the EU is to live up to its essence. The article suggests ten tentative guiding principles for the EU to continue turning such norms into practice. _____________________________________________________________________ The aftershock of the 2008 global financial crisis in the EU has come to be widely seen as a crisis of ‘democracy’ in Europe. This article starts from the premise that the EU’s legitimacy deficit will not be addressed by tinkering with its institutions. Instead, the name of the democratic game in Europe today is democratic interdependence: the Union magnifies the pathologies of the national democracies in its midst, even as it entrenches and nurtures these democracies, who in turn affect each other in profound ways. -

Discuss the Existence of a Demos Which Is Typically European and Which Would Thus Allow for the Construction of a Supranational European Democracy

“Why and how does the ‘Demos’ question matter” Discuss the existence of a demos which is typically European and which would thus allow for the construction of a supranational European Democracy Kalypso Nicolaidis University Of Oxford European Parliament, March 20th 2017 The Story you want to explore: Crisis Democratic Legitimacy Construct Supranational democracy “Existence of a European Demos”? Yes! Sources of legitimacy in Crisis Crisis Democratic And the Democratic sine Qua Non Legitimacy Purposive (Mission) Performative (Results) Process (Democracy) Crisis Democratic Legitimacy Construct …But, no! Supranational democracy Too narrow (democracy in Europe) “Existence of a European Demos”? Too mimetic (one nation, one state, one demos) Stubborn Sociology and the Yearning for Control (Somewheres vs Anywheres) The problem with Tainted ideology and the constructing supranational Poisened Well (“Oneness of democracy thanks to a People” populism, “typically” European demos technocracy and othering) Irrepressible modernity and the Technology of democracy (Chaotic Pluralism; self-construction and assemblages) The problem is both Empirical and Normative • Empirical : Do not wait for Godot • Normative: Who wants to ground Democracy in Europe (only/mostly) on a European Demos anyway! European democratic legitimacy is not just at EU-level but in the EU -> anchored in the democratic health of individual countries as they try to manage their democratic interdependence -> This is the genuine supranational mission What then of the “demos” in democracy?! -

Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation

King’s Research Portal Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kotsialou, G., & Riley, L. (Accepted/In press). Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation . In International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 2020: Social Choice and Cooperative Game Theory Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Our European Demoi-Cracy

Our European Demoi-cracy Is this Constitution a third way for Europe? kalypso nicolaidis* The tabloids have branded it as the biggest decision facing modern Britain, and the mark of its fi nal downfall. Ever since the draft Constitutional Treaty for the European Union started to take shape in bits an pieces last year it has provoked passion in Britain and a yawn in the rest of Europe. Public opinion may yet pick up elsewhere as the intergovernmental conference puts its own mark on the document and as a number of EU members put it to a referendum in the Spring. In the meanwhile, one can understand both the infl ated expectations and the indifference. For the fi rst time in the history of the EU, delegates other than diplomats have engaged for more than a year in a public debate about its foundations, its goals and its methods. The reach of their so- called dialogue with civil society may have been wanting, but they have conducted this debate in a highly open and transparent fashion, with the full paraphernalia of web cast and e-forum. But while the plot and the set may look impressive, the play itself is not revolutionary. For the most part, the draft European Constitution codifi es under one umbrella the plethora of treaties and amendments adopted by European Union members over the last 45 years. The idea that, with it, Britain would lose its unique identity is a strange one. Nevertheless, the draft Constitutional Treaty has a major fl aw which cannot help but antagonize Eurosceptics: its drafters seriously saw their task as writing a.. -

Liquid Democracy: an Algorithmic Perspective

Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 70 (2021) 1223-1252 Submitted 11/2020; published 03/2021 Liquid Democracy: An Algorithmic Perspective Anson Kahng [email protected] Computer Science Department Carnegie Mellon University Simon Mackenzie [email protected] University of New South Wales Ariel D. Procaccia [email protected] School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Harvard University Abstract We study liquid democracy, a collective decision making paradigm that allows voters to transitively delegate their votes, through an algorithmic lens. In our model, there are two alternatives, one correct and one incorrect, and we are interested in the probability that the majority opinion is correct. Our main question is whether there exist delegation mechanisms that are guaranteed to outperform direct voting, in the sense of being always at least as likely, and sometimes more likely, to make a correct decision. Even though we assume that voters can only delegate their votes to better-informed voters, we show that local delegation mechanisms, which only take the local neighborhood of each voter as input (and, arguably, capture the spirit of liquid democracy), cannot provide the foregoing guarantee. By contrast, we design a non-local delegation mechanism that does provably outperform direct voting under mild assumptions about voters. 1. Introduction Liquid democracy is a modern approach to voting in which voters can either vote directly or delegate their vote to other voters. In contrast to the classic proxy voting paradigm (Miller, 1969), the key innovation underlying liquid democracy is that proxies | who were selected by voters to vote on their behalf | may delegate their own vote to a proxy, and, in doing so, further delegate all the votes entrusted to them. -

Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation∗

Research Paper AAMAS 2020, May 9–13, Auckland, New Zealand Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation∗ Grammateia Kotsialou Luke Riley Political Economy - King’s College London Informatics - King’s College London, Quant Network London, United Kingdom London, United Kingdom [email protected] luke.riley@{kcl.ac.uk,quant.network} ABSTRACT Party in Argentina and Partido de Internet in Spain have been ex- Liquid democracy allows members of an electorate to either directly perimenting with liquid democracy implementations. Additionally, vote over alternatives, or delegate their voting rights to someone the local governments of the London Southwark borough and the they trust. Most of the liquid democracy literature and implementa- Italian cities Turino and San Dona di Piave are working on integrat- tions allow each voter to nominate only one delegate per election. ing liquid democracy for community engagement processes (Boella However, if that delegate abstains, the voting rights assigned to et al. [2018]). In the technology domain, the online platform Liq- her are left unused. To minimise the number of unused delegations, uidFeedback uses a liquid democracy system where a user selects it has been suggested that each voter should declare a personal a single guru for different topics (Behrens et al. [2014]; Kling etal. ranking over voters she trusts. In this paper, we show that even if [2015]). Another prominent online example is GoogleVotes (Hardt personal rankings over voters are declared, the standard delegation and Lopes [2015]), where each user wishing to delegate can select method of liquid democracy remains problematic. More specifically, a ranking over other voters. -

Selecting the Runoff Pair

Selecting the runoff pair James Green-Armytage New Jersey State Treasury Trenton, NJ 08625 [email protected] T. Nicolaus Tideman Department of Economics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] This version: May 9, 2019 Accepted for publication in Public Choice on May 27, 2019 Abstract: Although two-round voting procedures are common, the theoretical voting literature rarely discusses any such rules beyond the traditional plurality runoff rule. Therefore, using four criteria in conjunction with two data-generating processes, we define and evaluate nine “runoff pair selection rules” that comprise two rounds of voting, two candidates in the second round, and a single final winner. The four criteria are: social utility from the expected runoff winner (UEW), social utility from the expected runoff loser (UEL), representativeness of the runoff pair (Rep), and resistance to strategy (RS). We examine three rules from each of three categories: plurality rules, utilitarian rules and Condorcet rules. We find that the utilitarian rules provide relatively high UEW and UEL, but low Rep and RS. Conversely, the plurality rules provide high Rep and RS, but low UEW and UEL. Finally, the Condorcet rules provide high UEW, high RS, and a combination of UEL and Rep that depends which Condorcet rule is used. JEL Classification Codes: D71, D72 Keywords: Runoff election, two-round system, Condorcet, Hare, Borda, approval voting, single transferable vote, CPO-STV. We are grateful to those who commented on an earlier draft of this paper at the 2018 Public Choice Society conference. 2 1. Introduction Voting theory is concerned primarily with evaluating rules for choosing a single winner, based on a single round of voting. -

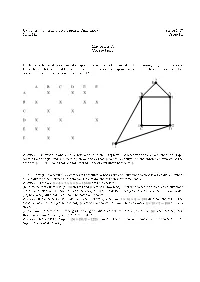

Midterm 2. Correction

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Spring 2007 Math 181 Group F1 Midterm 2. Correction. 1. The table below shows chemical compounds which cannot be mixed without causing dangerous reactions. Draw the graph that would be used to facilitate the choice of disposal containers for these compounds ; what is the minimal number of containers needed ? 2 E A B C D E F A X X X B A 3 1 B X X X X C X X D X X X 1 2 E X X C D F X X F 1 Answer. The graph is above ; a vertex-coloring of this graph will at least use three colors since the graph contains a triangle, and the coloring above shows that 3 colors is enough. So the chromatic number of the graph is 3, which means that the minimal number of containers needed is 3. 2. (a) In designing a security system for its accounts, a bank asks each customer to choose a ve-digit number, all the digits to be distinct and nonzero. How many choices can a customer make ? Answer. There are 9 × 8 × 7 × 6 × 5 = 15120 possible choices. (b) A restaurant oers 4 soups, 10 entrees and 8 desserts. How many dierent choices for a meal can a customer make if one selection is made from each category ? If 3 of the desserts are pie and the customer will never order pie, how many dierent meals can the customer choose ? Answer. If one selection is made from each category, there are 4 × 10 × 8 = 320 dierent choices ; if the customer never orders pie, he has only 5 desserts to choose from and thus can make 4 × 10 × 5 = 200 dierent choices. -

What Is Polyarchy? Q: How Do We Define Democracy in the Real World?

9/27 Q: What is democracy? Q: What is polyarchy? Q: How do we define democracy in the real world? Read this week: Ellis and Nelson, Chpt 1 (to discuss Friday) Monroe & Kersh Chpt 1 & 2 What makes the US (or anything) a Democracy? 1) 2) 3) etc) What makes the US (or anything) NOT a Democracy? 1) 2) 3) etc) I. Democratic Government A. What makes mass politics democratic? as opposed to: authoritarian / autocracy monarchy oligarchy republic etc. Traits of an “Ideal,” or pure Democracy: public opinion -> public policy 1. “Majority Rule” • 50% + 1 • full participation required 2. Public Discourse / Deliberation • perfect information • people seek out info on politics • full public discussion • full consideration of alternatives • people are interested 3. Perfect competition of groups/ideas • free entry into arena Is this "democracy"? What is left out of this definition? 1. ?? 2. ?? B. Can there ever be a perfect democracy? How do we know if/when a nation is democratic? In the real world: 1. Most people don’t vote 2. Most of us have little information about politics other things more important in daily life (job, bills, sports, love, sex, family, .......etc.) 3. People act on basis of emotion and reason 4. Institutions constrain choices • number of parties function of rules • market forces constrain media output So, what is a democracy? o In pure form, an ideal (utopia?) o In practice Q: How do we define democracy in the real world? Q: What is a republic (vs. a democracy)? “Ideal” view of Democracy something no real place can meet What real world criteria to define democracy? II.