Confronting Disinfo for SSRN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miss World 1970 by Jennifer Hosten, Coming Spring 2020 About Sutherland House

MISS WORLD 1970 BY JENNIFER HOSTEN, COMING SPRING 2020 ABOUT SUTHERLAND HOUSE Founded in 2017 by Canadian author and publishing executive Kenneth Whyte, Sutherland House is a new Toronto-based publisher of non-fiction books for global English-language audiences. Sutherland House specializes in narrative works of biography, memoir, history, business, culture, and current affairs. Aiming for high-quality and broad appeal, it published eight books in 2019 and will deliver nine in 2020. Each volume will be commissioned and edited by Mr. Whyte. All of our publications will bear the unique aesthetic of the Sutherland House brand, and be subjected to rigorous market testing from conception to launch. By maintaining a low overhead, the company is dedicating an unusually high portion of its resources to the promotion and mar- keting of its titles, which will be managed by our international network of service providers. Our Sutherland Classics series, which began in 2019 with the republication of Bernard Crick’s definitive George Orwell: A Life, is indicative of our commitment to quality non-fiction. We will reprint one or two masterpieces of biography, memoir, or character-driven history every year under the Sutherland Classics imprint. CONTACT INFORMATION CONTACT PUBLICITY SPRING 2020 THE SUTHERLAND HOUSE INC. [email protected] 416 Moore Ave, Suite 205 Toronto, ON M4G 109 RIGHTS INQUIRIES [email protected] MATTHEW BUCEMI [email protected] ORDERING INFORMATION CANADA WORLD UNIVERSITY OF BAKER AND TAYLOR TORONTO PRESS PUBLISHING SERVICES 5201 Dufferin Street 30 Amberwood Parkway Toronto, ON M3H 5T8 Ashland, OH 44805 Email: utpbooks@utpress. Tel: (888) 814-0208 utoronto.ca Email: [email protected] Misbehaviour, a major motion picture based on To be the luckiest kid in America, he first had to the author’s life and starring Keira Knightley and be the unluckiest. -

Terrorism Threat Assessment

Terrorism Threat Assessment 2018 – 2019 Liesbeth van der Heide & Reinier Bergema 8 Introduction The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT) developed a baseline Terrorism Threat Assessment. This assessment used open source data to present an assessment of terrorism in 32 countries across four categories: (1) Terrorist Attacks, (2) (Returning) Foreign Terrorist Fighters (RFTF), (3) Prison & Prosecution, and (4) Terrorism Threat Assessments. Methodology The time period of this situation report ranges from January 2018 until (and including) August 2019. The RFTF category concerns the total numbers of Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) and Returnees rather than just the numbers of RFTF for 2018-19. The Terrorism Threat Assessment category inquires after the availability of a National Threat Assessment or Terrorist Alert System in countries without specifying a timeframe. Collecting data on the number of terrorist attacks is a delicate task. The open source data gathering process includes a variety of sources, including EUROPOL’s TE-SAT 2019 and the 2019 update of the Global Terrorism Update, maintained by START. While both sources are considered among the most authoritative in the field, there is a discrepancy in the number of terrorist attacks reported (see box 1). This differentiation stems from a difference in definitions and methodology. To illustrate, EUROPOL reports on failed, foiled, and completed attacks, whereas the GTD only lists completed and failed attacks, excluding foiled attacks. Moreover, whereas the GTD has developed its own open source methodology, EUROPOL collects “qualitative and quantitative data on terrorist offences in the EU and data on arrests […] provided or confirmed by EU Member States”. -

Nurturing Media Vitality in Quebec's English-Speaking Minority

Brief to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Nurturing Media Vitality in Quebec’s English-speaking Minority Communities Presented by the Quebec Community Groups Network April 12, 2016 Introduction The Quebec Community Groups Network, or QCGN, is a not-for-profit representative organization. We serve as a centre of evidence-based expertise and collective action. QCGN is focused on strategic issues affecting the development and vitality of Canada’s English linguistic minority communities, to which we collectively refer as the English-speaking community of Quebec. Our 48 members are also not-for-profit community groups. Most provide direct services to community members. Some work regionally, providing broad-based services. Others work across Quebec in specific sectors such as health, and arts and culture. Our members include the Quebec Community Newspaper Association (QCNA). English-speaking Quebec is Canada’s largest official language minority community. A little more than 1 million Quebecers specify English as their first official spoken language. Although 84 per cent of our community lives within the Montreal Census Metropolitan Area, more than 210,000 community members live in other Quebec regions. Media Landscape English-speaking Quebecers have consistently signalled that access to information in their own language is both a need and a priority (CHSSN-CROP survey, various years). This may seem a bit of a contradiction in a world awash in English language information through CNN, Time magazine and Hollywood movies galore. The important nuance is that English- speaking Quebecers need information in their own language about their own local and regional communities, something that is increasingly hard to access on a consistent basis in a context of the francization of daily life in Quebec and the demise of traditional community media. -

1 Submission with Respect to the Interpretation and Application of Section 19 of the Compensation for Victims of Crime Act

Submission with respect to the interpretation and application of section 19 of the Compensation for Victims of Crime Act, RSO 1990, c. C. 24 as amended June 6, 2018 Context and Recommendation The Criminal Injuries Compensation Board (thereafter, “CICB”) has invited the Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime (thereafter, “CRCVC”) to provide a written submission with respect to the interpretation and application of section 19 of the Compensation for Victims of Crime Act, RSO 1990, c. C. 24, as amended (thereafter, the “Act”). With respect to the events of April 23, 2018, the CRCVC respectfully recommends that the CICB not deem the acts referred to in the current and all future claims as a single occurrence. The CRCVC will delve into the complex nature of the events that unfolded on April 23, 2018, including the gravity, extent, and scope of the crime and its victims; examine the intricacies of victimization, both in its effects and needs; comment on the particular issue of mass victimization; and survey the legal framework, providing legal precedent. Background on the CRCVC The Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime (CRCVC) provides support and guidance to individual victims and their families in order to assist them in obtaining needed services and resources, and advances victims’ rights by presenting the interests and perspectives of victims of crime to Government, at all levels. We also strive to foster heightened public awareness of victims’ issues, conduct research in the field of victimology and promote exchanges between professionals at the local, provincial and national level. The CRCVC helps victims of violence and has front-line experience supporting victims of mass violence. -

To Your All Access Subscription

WELcoME TO YOUR ALL ACCESS SUBSCRIPTION We hope you enjoy the benefits of your SUN All Access subscription HOW TO REACH US which includes our print, mobile, tablet and web content. Online: SUBSCRIBER SERVICES: torontosun.com/ As part of our commitment to quality service we have our subscriber contact-us services available to you 24/7 at torontosun.com/subscription/ my-subscription Enjoy the convenience of managing your account Email: online including: webservices@ sunmedia.ca a Pay bills a Renew your subscription Phone: 416-947-2111 a Add a vacation stop and restart Toll-Free 1-800-668-0786 a Inform us of a home delivery concern a Update delivery address Monday — Friday 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. (Eastern Standard Time) YOUR SUN ALL ACCESS SUBSCRIPTION INCLUDES: a Convenient home delivery Saturday — Sunday 8:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon a Unlimited access to torontosun.com (Eastern Standard Time) a Toronto SUN smartphone app a Toronto SUN ePaper Activate your SUN All Access subscription at: torontosun.com/subscription/my-subscription toroNto suN CONTENT CALENDAR WEEKDAYS WEEKENDS Strong daily focus on Toronto news Compelling local news and features on presented in a lively, contextual and Toronto, the GTA and Ontario digestible format. Key national and international news In depth sports news, features and opinion on the Maple Leafs, Argonauts, Raptors, Canada’s best and most comprehensive Blue Jays, TFC and Toronto Rock delivered Sports coverage in a daily, pull-out sports by the strongest sports team in the country section featuring renowned sports writer Steve Simmons Five pages of engaging and critical editorial commentary on national and local issues Compelling editorial Comment from opinion leaders Lorrie Goldstein, Sue- Great Lifestyle and weekend Ann Levy, Farzana Hassan, Tarek Fatah, entertainment reads including the Daily Anthony Furey and Mark Bonokoski Dish, moving listings and concert reviews Life, Food and Recipes with Rita Demontis and the latest in showbiz news from Sunshine Girl Hollywood insiders. -

Callitfemicide Understanding Gender-Related Killings of Women and Girls in Canada 2018

#CallItFemicide Understanding gender-related killings of women and girls in Canada 2018 https://femicideincanada.ca CAN_Femicide CAN.Femicide [email protected] https://femicideincanada.ca Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................... 4 Suicide: ................................................................................... 28 Foreward ................................................................................. 5 Case outcome/status ............................................................ 28 Dedication ............................................................................... 6 SECTION III: Understanding gender-based motives/indicators for femicide ........................................................................... 28 Executive Summary ................................................................. 7 What relationships did women and girls share with male Introduction ............................................................................ 9 accused? ............................................................................... 30 Why focus on the killings of women and girls? ...................... 9 Gender-based motive/indicator #1: Misogyny ..................... 31 Structure of this report ......................................................... 10 Gender-based motive/indicator #2: Sexual violence ........... 32 SECTION I: The history and evolution of the term ‘femicide’ 12 Patterns in intimate femicide .............................................. -

CMCRP : the Growth of the Network Media Economy in Canada

THE GROWTH OF THE NETWORK MEDIA ECONOMY IN CANADA, 1984-2017 REPORT NOVEMBER 2018 (UPDATED JANUARY 2019) Canadian Media Concentration Research Project Research Canadian Media Concentration www.cmcrp.org 2 Candian Media Concentration Research Project The Canadian Media Concentration Research project is directed by Professor Dwayne Winseck, School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University. The project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and aims to develop a comprehensive, systematic and long-term analysis of the media, internet and telecom industries in Canada to better inform public and policy-related discussions about these issues. Professor Winseck can be reached at either [email protected] or 613 769- 7587 (mobile). Open Access to CMCR Project Data CMCR Project data can be freely downloaded and used under Creative Commons licens- ing arrangements for non-commercial purposes with proper attribution and in accor- dance with the ShareAlike principles set out in the International License 4.0. Explicit, written permission is required for any other use that does not follow these principles. Our data sets are available for download here. They are also available through the Dat- averse, a publicly-accessible repository of scholarly works created and maintained by a consortium of Canadian universities. All works and datasets deposited in Dataverse are given a permanent DOI, so as to not be lost when a website becomes no longer avail- able—a form of “dead media”. Acknowledgements Special thanks to Ben Klass, a Ph.D. student at the School of Journalism and Communi- cation, Carleton University, Lianrui Jia, a Ph.D student in the York Ryerson Joint Gradu- ate Program in Communication and Culture and Han Xiaofei, also in the Ph.D. -

Open Secret: Kevin Donovan’S Account of the Ghomeshi Investigation Is Comprehensive, but Not Revelatory

Open secret: Kevin Donovan’s account of the Ghomeshi investigation is comprehensive, but not revelatory Book Review by David Hayes, The National Post, October 17, 2016 Secret Life: The Jian Ghomeshi Investigation By Kevin Donovan Goose Lane 260 pp; $19.95 Several years ago, while talking to one of my former feature writing students, Jian Ghomeshi’s name came up. I often listened to Ghomeshi hosting CBC Radio’s Q, and thought he was an effective interviewer whose hushed, intimate voice was made for radio. My former student, a talented young woman in her late 20s, said to me, “do you know the joke about Jian Ghomeshi? If you’re a female journalist in your 20s working in the arts in Toronto, he’s hit on you.” I was surprised but then thought, why should I be? It’s a common enough scenario and, if true, I would think less of Ghomeshi, but assumed it meant he was one of those middle-aged celebrities fixated on young women. Not admirable, perhaps, but also not criminal. When the Ghomeshi scandal became public — driven by the reporting of independent media critic Jesse Brown and triggered by Ghomeshi’s rambling Facebook post in which the former broadcaster admitted to a taste for consensual rough sex — it was catnip for the media. As weeks passed, more women came forward, mainly anonymously, with disturbing stories of choking, punching and sexual assault, initially on Brown’s Canadaland site and, later, in The Toronto Star when Brown entered into a partnership with the paper’s investigative unit and the coverage grew exponentially. -

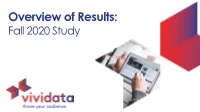

Overview of Results: Fall 2020 Study STUDY SCOPE – Fall 2020 10 Provinces / 5 Regions / 40 Markets • 32,738 Canadians Aged 14+ • 31,558 Canadians Aged 18+

Overview of Results: Fall 2020 Study STUDY SCOPE – Fall 2020 10 Provinces / 5 Regions / 40 Markets • 32,738 Canadians aged 14+ • 31,558 Canadians aged 18+ # Market Smpl # Market Smpl # Market Smpl # Provinces 1 Toronto (MM) 3936 17 Regina (MM) 524 33 Sault Ste. Marie (LM) 211 1 Alberta 2 Montreal (MM) 3754 18 Sherbrooke (MM) 225 34 Charlottetown (LM) 231 2 British Columbia 3 Vancouver (MM) 3016 19 St. John's (MM) 312 35 North Bay (LM) 223 3 Manitoba 4 Calgary (MM) 902 20 Kingston (LM) 282 36 Cornwall (LM) 227 4 New Brunswick 5 Edmonton (MM) 874 21 Sudbury (LM) 276 37 Brandon (LM) 222 5 Newfoundland and Labrador 6 Ottawa/Gatineau (MM) 1134 22 Trois-Rivières (MM) 202 38 Timmins (LM) 200 6 Nova Scotia 7 Quebec City (MM) 552 23 Saguenay (MM) 217 39 Owen Sound (LM) 200 7 Ontario 8 Winnipeg (MM) 672 24 Brantford (LM) 282 40 Summerside (LM) 217 8 Prince Edward Island 9 Hamilton (MM) 503 25 Saint John (LM) 279 9 Quebec 10 Kitchener (MM) 465 26 Peterborough (LM) 280 10 Saskatchewan 11 London (MM) 384 27 Chatham (LM) 236 12 Halifax (MM) 457 28 Cape Breton (LM) 269 # Regions 13 St. Catharines/Niagara (MM) 601 29 Belleville (LM) 270 1 Atlantic 14 Victoria (MM) 533 30 Sarnia (LM) 225 2 British Columbia 15 Windsor (MM) 543 31 Prince George (LM) 213 3 Ontario 16 Saskatoon (MM) 511 32 Granby (LM) 219 4 Prairies 5 Quebec (MM) = Major Markets (LM) = Local Markets Source: Vividata Fall 2020 Study 2 Base: Respondents aged 18+. -

Asper Nation Other Books by Marc Edge

Asper Nation other books by marc edge Pacific Press: The Unauthorized Story of Vancouver’s Newspaper Monopoly Red Line, Blue Line, Bottom Line: How Push Came to Shove Between the National Hockey League and Its Players ASPER NATION Canada’s Most Dangerous Media Company Marc Edge NEW STAR BOOKS VANCOUVER 2007 new star books ltd. 107 — 3477 Commercial Street | Vancouver, bc v5n 4e8 | canada 1574 Gulf Rd., #1517 | Point Roberts, wa 98281 | usa www.NewStarBooks.com | [email protected] Copyright Marc Edge 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (access Copyright). Publication of this work is made possible by the support of the Canada Council, the Government of Canada through the Department of Cana- dian Heritage Book Publishing Industry Development Program, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Printing, Cap-St-Ignace, QC First printing, October 2007 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Edge, Marc, 1954– Asper nation : Canada’s most dangerous media company / Marc Edge. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55420-032-0 1. CanWest Global Communications Corp. — History. 2. Asper, I.H., 1932–2003. I. Title. hd2810.12.c378d34 2007 384.5506'571 c2007–903983–9 For the Clarks – Lynda, Al, Laura, Spencer, and Chloe – and especially their hot tub, without which this book could never have been written. -

JIHADIST TERRORISM 17 YEARS AFTER 9/11 a Threat Assessment

PETER BERGEN AND DAVID STERMAN JIHADIST TERRORISM 17 YEARS AFTER 9/11 A Threat Assessment SEPTEMBER 2018 About the Author(s) Acknowledgments Peter Bergen is a journalist, documentary producer, The authors would like to thank Wesley Je�eries, John vice president for global studies & fellows at New Luebke, Melissa Salyk-Virk, Daiva Scovil, and Tala Al- America, CNN national security analyst, professor of Shabboot for their research support on this paper. The practice at Arizona State University where he co- authors also thank Alyssa Sims and Albert Ford, who directs the Center on the Future of War, and the co-authored the previous year’s assessment which author or editor of seven books, three of which were forms the basis of much of this report. New York Times bestsellers and four of which were named among the best non-�ction books of the year by The Washington Post. David Sterman is a senior policy analyst at New America and holds a master's degree from Georgetown’s Center for Security Studies. About New America We are dedicated to renewing America by continuing the quest to realize our nation’s highest ideals, honestly confronting the challenges caused by rapid technological and social change, and seizing the opportunities those changes create. About International Security The International Security program aims to provide evidence-based analysis of some of the thorniest questions facing American policymakers and the public. We are focused on South Asia and the Middle East, extremist groups such as ISIS, al Qaeda and allied groups, the proliferation of drones, homeland security, and the activities of U.S. -

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 Papers)

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 papers) ALTA Newspaper Group/Glacier (3) CN2i (6) Independent (6) Quebecor (2) Lethbridge Herald # Le Nouvelliste, Trois-Rivieres^^ Prince Albert Daily Herald Le Journal de Montréal # Medicine Hat News # La Tribune, Sherbrooke^^ Epoch Times, Vancouver Le Journal de Québec # The Record, Sherbrooke La Voix de l’Est, Granby^^ Epoch Times, Toronto Le Soleil, Quebec^^ Le Devoir, Montreal Black Press (2) Le Quotidien, Chicoutimi^^ La Presse, Montreal^ SaltWire Network Inc. (4) Red Deer Advocate Le Droit, Ottawa/Gatineau^^ L’Acadie Nouvelle, Caraquet Cape Breton Post # Vancouver Island Free Daily^ Chronicle-Herald, Halifax # The Telegram, St. John’s # Brunswick News Inc. (3) The Guardian, Charlottetown # Times & Transcript, Moncton # Postmedia Network Inc./Sun Media (33) The Daily Gleaner, Fredericton # National Post # The London Free Press Torstar Corp. (7) The Telegraph-Journal, Saint John # The Vancouver Sun # The North Bay Nugget Toronto Star # The Province, Vancouver # Ottawa Citizen # The Hamilton Spectator Continental Newspapers Canada Ltd.(3) Calgary Herald # The Ottawa Sun # Niagara Falls Review Penticton Herald The Calgary Sun # The Sun Times, Owen Sound The Peterborough Examiner The Daily Courier, Kelowna Edmonton Journal # St. Thomas Times-Journal St. Catharines Standard The Chronicle Journal, Thunder Bay The Edmonton Sun # The Observer, Sarnia The Tribune, Welland Daily Herald-Tribune, Grande Prairie The Sault Star, Sault Ste Marie The Record, Grand River Valley F.P. Canadian Newspapers LP (2) The Leader-Post, Regina # The Simcoe Reformer Winnipeg Free Press The StarPhoenix, Saskatoon # Beacon-Herald, Stratford TransMet (1) Brandon Sun Winnipeg Sun # The Sudbury Star Métro Montréal The Intelligencer, Belleville The Daily Press, Timmins Glacier Media (1) The Expositor, Brantford The Toronto Sun # Times Colonist, Victoria # The Brockville Recorder & Times The Windsor Star # The Chatham Daily News The Sentinel Review, Woodstock Globe and Mail Inc.