The Power of Words

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Botswana Health Professions Council (BHPC) Before Seeing Patients

BHPC Application Instructions for BUP Travelers Just as no person would be allowed to walk onto the wards of HUP or any other US hospital and begin treating patients without presenting their credentials, no one may practice in any hospital or clinic in Botswana without official permission. Any physician practicing medicine in Botswana is required to register with the Botswana Health Professions Council (BHPC) before seeing patients. To register you must bring the following documents with you to Botswana: 4 x passport photos 1 x notarized copy of passport photo page 2 x letters of recommendation from doctors/supervisors you work with (letters to be original, no digital copies allowed by BHPC, dated no older than six months) 1 x notarized copy of your medical degree/diploma 1 x notarized copy of your state medical license/registration 1 x CV Copy of offer letter (provided in Botswana) Cover letter of application form (provided in Botswana) Application fee (P30 ≈ $3) BUP staff will assist you in completing the application (pp 3-6 of this document) in country and take you to the BHPC on your first day during orientation to submit the forms and then again on the Wednesday following arrival to receive your approval. Note that you cannot practice medicine until the BHPC registration is completed. You should plan to arrive in Botswana on the weekend prior to when you plan to work so that your BHPC application can be turned in on Monday and you can receive registration certification on Wednesday afternoon. You will then be able to start to practice medicine on Thursday. -

Pre-Med & Other Health Programs

PRE-MED & OTHER HEALTH PROGRAMS Berkeley offers excellent undergraduate preparation for medical and other health-related professional schools and sends an impressive number of students on to these graduate programs each year. Cal, like most universities, does not offer a specific “pre-med” major. Few colleges in the United States do, because there is no specific major required for admission to medical or other health- related schools. All students obtain a bachelor’s degree before admission to medical school. For students seeking admission to dentistry, veterinary medicine, optometry, and other health- related graduate programs, many have received a bachelor’s degree prior to admission. What should I major in at Berkeley, AP credits will not satisfy prerequisites at most Does it make a difference where I if I want to go to medical school? medical schools.) Select an academic major that complete my academic preparation for interests you and allows flexibility in taking the There is no preferred pre-med major. Every year medical or other health-related schools? required pre-med courses. students with majors in the social sciences, The quality and reputation of the college or humanities, chemistry and engineering are What should I do when I’m not in class? university from which you graduate can play a accepted to medical school from Berkeley. role in your acceptance to a medical school. If you want to study biology at Berkeley, you One option is to experience the health care The high quality of Berkeley students and can choose from more than 25 areas of environment in a paid or volunteer position during the campus’ worldwide academic reputation specialization in the biological sciences, such college. -

Allied Health Professionals Consumer Fact Sheet Board of Registration of Allied Health Professionals

Allied Health Professionals Consumer Fact Sheet Board of Registration of Allied Health Professionals The Board of Registration in Allied Health evaluates the qualifications of applicants for licensure and grants licenses to those who qualify. It establishes rules and regulations to ensure the integrity and competence of licensees. The Board is the link between the consumer and the allied health professional and, as such, promotes the public health, welfare and safety. Allied health professionals are occupational therapists and assistants, athletic trainers, and physical therapists and assistants. Occupational Therapists/Occupational Therapist Assistants Occupational therapists are health professionals who use occupational activities with specific goals in helping people of all ages to prevent, lessen or overcome physical, psychological or developmental disabilities. Occupational Therapists and Occupational Therapist Assistants help people with physical, psychological, or developmental problems regain abilities or adjust to handicaps. They work with physicians, physical and speech therapists, nurses, social workers, psychologists, teachers and other specialists. Patients may face handicaps, injuries, illness, psychological or social problems, or barriers due to age, economic, and cultural factors. Occupational Therapists: Consult with treatment teams to develop individualized treatment programs. Select and teach activities based on the needs and capabilities of each patient Evaluate each patient's progress, attitude and behavior. Design special equipment to aid patients with disabilities. Teach patients how to adjust to home, work, and social environments. Test and evaluate patients' physical and mental abilities. Educate others about occupational therapy. The goal of occupational therapy (OT) is for persons to achieve the highest level of independence after an injury or illness. OT addresses the whole person - cognitive, physical and emotional status. -

Allied Health Professionals

POLICY and PROCEDURE TITLE: Allied Health Professionals Number: 13373 Version: 13373.3 Type: Administrative - Medical Staff Author: Martha Hoover Effective Date: 1/15/2015 Original Date: 8/31/1997 Approval Date: 1/8/2015 Deactivation Date: Facility: Banner Churchill Community Hospital Population (Define): Medical Staff Replaces: Approved by: Medical Executive Committee, Banner Health Board TITLE: Allied Health Professionals I. Purpose/Expected Outcome: A. To allow Allied Health Professionals to function at Banner Churchill Community Hospital (the Hospital) in strict compliance with this Policy and applicable sections of the Medical Staff Bylaws and Rules and Regulations of the Medical Staff, subject to the continuing approval of the Medical Executive Committee and the Governing Board of Banner Health. B. This policy contains the credentialing process for Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) at Banner Churchill Community Hospital as well as the general parameters for the functioning of these individuals within the Hospital. All such AHPs who are permitted to practice at the Hospital fall within two (2) broad categories, Independent Allied Health Professionals and Dependent Allied Health Professionals, each having a slightly different relationship to the hospital. II. Definitions: A. ALLIED HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: The term “Allied Health Professionals” means those Dependent Allied Health Professionals and Independent Allied Health Professionals, also referred to as practitioners, who are permitted to evaluate and/or treat patients at Banner Churchill Community Hospital, but who are not members of the Medical Staff. Allied Health Professionals may also be employees of Banner Churchill Community Hospital. B. MEDICAL STAFF: The term “Medical Staff” means the formal organization of all licensed physicians, dentists and podiatrist who are credentialed and privileged to attend patients at Banner Churchill Community Hospital. -

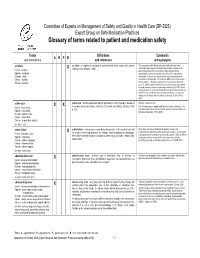

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

The Role of the Health Professional in Supporting Self Care

Quality in Primary Care 2006;14:129–31 # 2006 Radcliffe Publishing Guest editorial The role of the health professional in supporting self care Ruth Chambers DM FRCGP Professor of Primary Care, Faculty of Health and Sciences, Staffordshire University, Stoke-on-Trent, and Director of Postgraduate General Practice Education, West Midlands Deanery, Birmingham, UK It is widely believed that patients who adopt self care Safety concerns practices, will reduce demand on general practitioners (GPs) and other providers of healthcare as a whole.1 The evidence base that justifies self care is wide- Safety concerns tend not to feature in research reports ranging, but robust evidence of the cost-effectiveness or policies of those advocating or trialling patients’ self of increased self care by patients is awaited, in terms of care;2,5,6 yet there are potential adverse events for most better health outcomes for patients, more appropriate health conditions if medical care is not sought or consultations with the healthcare team, and savings on obtained appropriately.7–10 So, inappropriate self care providing healthcare.1,2 There may be displaced costs. could be costly for the individual person if they suffer For example, more appropriate consultation behav- harm from waiting too long before seeking medical iour by patients with doctors could lead to increased help, or pursue self care with an ineffectual or harmful consultation rates with other primary care professionals treatment. It could rebound on the NHS if the result of such as pharmacists, or with primary -

Glossary of Commonly Used Health Care Terms and Acronyms

GLOSSARY OF COMMONLY USED HEALTH CARE TERMS AND ACRONYMS Vermont Health Care Resources 1 Health Care Terms A and dividends, as well as conducted other statistical studies. academic medical center A group of acute care Medical treatment rendered to related institutions including a teaching individuals whose illnesses or health hospital or hospitals, a medical school and problems are of short-term or episodic its affiliated faculty practice plan, and other nature. Acute care facilities are those health professional schools. hospitals that mainly serve persons with short-term health problems. access An individual’s ability to obtain appropriate health care services. Barriers to acute disease A disease characterized by a access can be financial (insufficient single episode of a relatively short duration monetary resources), geographic (distance to from which the patient returns to his/her providers), organizational (lack of available normal or pervious state of level of activity. providers) and sociological (e.g., While acute diseases are frequently discrimination, language barriers). Efforts to distinguished from chronic diseases, there is improve access often focus on no standard definition or distinction. It is providing/improving health coverage. worth noting that an acute episode of a chronic disease (for example, an episode of accident insurance A policy that provides diabetic coma in a patient with diabetes) is benefits for injury or sickness directly often treated as an acute disease. resulting from an accident. adjusted average per capita cost accreditation A process whereby a program (AAPCC) The basis for HMO or CMP of study or an institution is recognized by an (Competitive Medical Plan) reimbursement external body as meeting certain under Medicare-risk contracts. -

Glossary of Terms

CCMC Glossary of Terms Published by the Commission for Case Manager Certification (CCMC) www.ccmcertification.org Glossary of Terms DISCLAIMER: The glossary of terms is a list of terms directly or indirectly related to the practice of case management compiled by members of CCMC’s Exam and Research Committee (ERC) and based on published literature related to case management. The list is not meant to be exhaustive. It is organized based on major aspects of case management practice. Each term is included in the category deemed most appropriate based on the judgment of ERC members. Please note that not every term will appear on the examination. CCMC suggests that candidates for the CCM exam be familiar with terms and concepts relevant to case management. This list should be helpful in that regard. Martine Johnston © 2017 Commission for Case Manager Certification (CCMC) Please be sure to read the disclaimer located on the cover page of this document November 2017 CCMC Glossary of Terms Term Definition AAPM&R American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation access to care The ability and ease of clients to obtain healthcare when they need it. A term used to denote building facilities that are barrier-free accessible thus enabling all members of society safe access, including persons with physical disabilities. A set of healthcare providers including primary care physicians, specialists, and hospitals that work together collaboratively and accept collective accountability for the cost and quality of care delivered to a population of patients. ACOs became popular in the Medicare fee-for-service benefit system as a result of the Affordable Care Act. -

Health Care Transformation: the Affordable Care Act and More

Updated June 18, 2014 Health Care Transformation: the Affordable Care Act and More Health care costs have been rising, quality of care issues must be addressed, and equity of healthcare access needs to be improved. For these reasons, though there is disagreement about some aspects of reform, most Americans agree that healthcare delivery systems in the United States require significant restructuring and improvement. ANA has long been a strong advocate of health care reform, and many of the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) align with ANA’s Health System Reform Agenda This chart offers information about recent and proposed health system changes with implications for nurses and nursing. Currently, most of the changes presented here reflect provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law 111-148) (ACA). ANA invites you to continue to follow updates to this chart that reflect nursing’s progress in influencing regulations and other activity to implement health reform and specific provisions of the ACA in the wake of the Supreme Court decision upholding most of the law. This chart also spotlights opportunities for RNs and APRNs to take advantage of new programs and pilot for healthcare innovations, and funding and grants for education and nursing workforce development. On June 28, 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld almost all provisions of the ACA, including the “shared responsibility” to purchase health insurance (so- called “individual mandate”). By upholding this cornerstone of the law, a multitude of other provisions survived challenge, including scores of important advances for the nursing profession and individual nurses, detailed in this chart. -

HEALTH PROFESSIONAL MOBILITY and HEALTH SYSTEMS 23 EVIDENCE from 17 EUROPEAN COUNTRIES Edited by Matthias Wismar, Claudia B

Cover_WHO_nr23_Mise en page 1 6/10/11 17:59 Page1 23 HEALTH PROFESSIONAL MOBILITY AND HEALTH SYSTEMS PROFESSIONAL MOBILITY AND HEALTH HEALTH Health professional mobility affects the performance of health systems and these EVIDENCE FROM 17 EUROPEAN COUNTRIES impacts are assuming greater significance given increasing mobility in Europe, a Health Professional 23 process fuelled by the European Union (EU) enlargements in 2004 and 2007. This volume presents research conducted within the framework of the European Commission’s Health PROMeTHEUS project. This research was undertaken in order to address gaps in the knowledge of the numbers, trends and impacts and of the policy Mobility and Health responses to this dynamic situation. Observatory Observatory The following questions were used to provide analytical guidance for the 17 country Studies Series case studies reported here: from Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Systems Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey and the United Kingdom. • What are the scale and characteristics of health professional mobility in the EU? Evidence from • What have been the effects of EU enlargement? 17 European countries • What are the motivations of the mobile workforce? • What are the resulting impacts on health system performance? Edited by Matthias Wismar • What is the policy relevance of those impacts? Claudia B. Maier • What are the policy options to address health professional mobility issues? Irene A. Glinos Gilles Dussault Josep Figueras The editors Matthias Wismar is Senior Health Policy Analyst at the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Irene A. Glinos, Gilles Dussault, Josep Figueras Josep Gilles Dussault, Glinos, Irene A. -

Recent Health Professional School Acceptance Information (11/15)

Recent Health Professional School Acceptance information (11/15) Medical Schools information is at the top of this document with other Health Profession information following Graphs and statistics will give all students an idea of what they will need to do. The information will give current students an idea of where they are regarding their academic record and acceptance benchmarks. AAMC Medical Schools (American MD programs) Acceptance Rates. It is very hard to compare acceptance numbers across institutions. Everyone measures rates differently and may report on different populations. The resources and collective knowledge of an institution should be the important things to compare and ask about as you visit schools. What you do to prepare and succeed determines your acceptance in a professional school. Your job now should be to find a school which is a good fit for you and has a broad range of strengths, while having good HPA resources and programming. Since you will find acceptance rates reported at other institutions, three different ways to measure the acceptance rates of our students are given below. Remember, we are not gate-keepers at Rhodes, all students who want to apply from Rhodes are assisted. This is not true of all programs. Any student at Rhodes who participates in any of our programming is considered to be in our HPA program. Our Medical acceptance rate for only our graduating seniors going straight to AAMC Medical Schools for 2009-2014 seniors (6 yrs) averages 65%. This is 56% greater than 2014 national overall acceptance rate. However more than 20% of our successful first-time applicants apply at graduation or as recent alumni and are not counted in this statistic. -

2020 Health Professional Underserved Areas Report

HEALTH PROFESSIONAL UNDERSERVED AREAS REPORT Kansas Primary Care and Rural Health Information provided for Calendar Year 2020 Laura Kelly, Governor State of Kansas Lee Norman, M.D., Secretary Kansas Department of Health and Environment Bureau of Community Health Systems Community Health Access Office of Primary Care and Rural Health Curtis State Office Building 1000 SW Jackson, Suite 340 785-296-1200 (voice) 785-559-4247 (fax) [email protected] www.kdheks.gov/bchs This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance awards totaling $475,804.00 with 100% funded by HRSA/HHS and $690,000 and 0% funded by nongovernment source(s). The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA/HHS, or the U.S. Government. Individuals and families with economic barriers to EXECUTIVE SUMMARY health care are found in almost all communities in Kansas. The Kansas Department of Health and Environment (KDHE) Bureau of Local and The SOPC-RH administers a number of Rural Health was established in 1989, to assist programs created to address these issues, communities in ensuring access to primary and such as state and federal scholarships, loan preventive health care services for all Kansas repayment or forgiveness programs, and federal residents. The office has since expanded and agency sponsorship of international medical is now housed in the Bureau of Community graduates; other programs, available directly Health Systems (BCHS), and the Community through federal agencies, include payment Health Access Section.