The History of Running and the USRSA As I Know It By: John Strumsky, Founder April 30, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Longboat and the First World War Robert K. Hanks1 in May 1919

Tom Longboat and the First World War Robert K. Hanks1 In May 1919, Tom Longboat returned to Toronto after serving just over three years in the Canadian army and two years overseas in Europe. When asked by the prominent Toronto Daily Star sports reporter, Lou Marsh, what he had done “over there”, Tom simply replied: “Oh, anything – carrying messages, running, dispatch riding and digging ditches.” This taciturn reply prompted Marsh to complain to his readers: “In my time I’ve interviewed everything from a circus lion to an Eskimo chief, but when it comes down to being the original dummy, Tom Longboat is it. Interviewing a Chinese Joss or a mooley cow is plo compared to the task of digging anything out of Heap Big Chief T. Longboat.” [sic] But if Marsh had been able to see past his own racist stereotypes and his subject’s tendency toward self- deprecating understatement, Tom had indeed outlined his experience in the Canadian armed forces.2 Whereas most previous studies on Tom have understandably focused on his illustrious pre-war running career,3 a deeper examination of his life between 1916-19 indicates that the First World War had a more profound impact on his life and running career than previously understood. “Running” When the First World War began in 1914, Tom was entering the autumnal stages of his great career as a runner. He was still a strong athlete, but his most famous victories were behind him. Moreover, the pre-war depression reduced the amount of disposable income in the 1 Thanks to Daphne Tran for suggesting this topic to me and to Amy Stupavsky for encouraging me to write it. -

ANNUAL Report 2013-2014 Athletics Annual Report 2014 Layout 1 8/07/2014 2:49 Pm Page 2

ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 Athletics Annual Report 2014_Layout 1 8/07/2014 2:49 pm Page 2 2013–2014 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Company Information . .1 Directors’ Profiles . .2 Chairman’s Report . .4 CEO’s Report . .6 Directors’ Report . .9 Auditor’s Independence Declaration under section 307C of the Corporations Act 2001 . .13 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income . .14 Statement of Financial Position . .15 Statement of Changes in Equity . .16 Statement of Cash Flows . .17 Notes to the Financial Statements . .18 Directors’ Declaration . .25 Independent Audit Report . .26 Disclaimer . .28 Detailed Profit and Loss Statement . .29 Membership and Club Administration . .31 Membership Statistics . .32 Competition . .36 Records . .39 Officials . .40 Development . .41 Hunter Region . .42 Greater Western Sydney Region . .44 Target Talent Program . .45 Marketing . .47 NSW Champions . .50 NSW Roll of Honour . .59 Athletics NSW Awards . .61 Life Members . .63 Merit Awards . .64 Condolences . .65 ATHLETICS NSW LIMITED ABN 11 330 775 869 FOUNDED 20 APRIL 1887, INCORPORATED 15 JANUARY 1996 Postal Address: PO Box 595, Sydney Markets, NSW 2129 Street Address: Sydney Olympic Park Athletic Centre, This report covers the period 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014 Edwin Flack Drive, Sydney Olympic Park, NSW 2127 unless specified otherwise Edited by Janet Naylon Proofreading by Betty Moore Telephone: (02) 9746 1122 Designed and printed by KDR Design and Print Facsimile: (02) 9746 1168 Photographs by David Tarbotton, Andrew Atkinson-Howatt, Email: [email protected] -

Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912– 1921 By: Adam Berg, Mark Dyreson Berg, A

The Flying Finn's American Sojourn: Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912– 1921 By: Adam Berg, Mark Dyreson Berg, A. & Dyreson, M. (2012). The Flying Finn’s American Sojourn: Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912-1921. International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(7), 1035-1059. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in International Journal of the History of Sport on 15 May 2012, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 Made available courtesy of Taylor & Francis: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 ***© Taylor & Francis. Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Taylor & Francis. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: Shortly after he won three gold medals and one silver medal in distance running events at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, Finland's Hannes Kolehmainen immigrated to the United States. He spent nearly a decade living in Brooklyn, plying his trade as a mason and dominating the amateur endurance running circuit in his adopted homeland. He became a naturalised US citizen in 1921 but returned to Finland shortly thereafter. During his American sojourn, the US press depicted him simultaneously as an exotic foreign athlete and as an immigrant shaped by his new environment into a symbol of successful assimilation. Kolehmainen's career raised questions about sport and national identity – both Finnish and American – about the complexities of immigration during the floodtide of European migration to the US, and about native and adopted cultures in shaping the habits of success. -

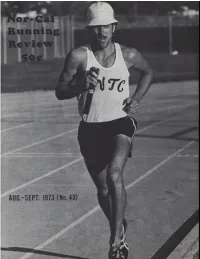

Norcal Running Review

The Northern California Running Review, formerly the West Ramirez. Juan is a freshman at San Jose City College and lives Valley Newsletter. is published on a monthly basis by the West at 64.6 Jackson Ave., San Jose, 95116 (Apt. 9) - Ph. 258-9865. Valley Track Club of San Jose, California. It is a communica- At 19, Juan has best times of 1:59.7, 4:28.3, and 9:51.7. He tion medium for all Northern California track and field ath- ran 19:45 for four miles cross country this past season, and letes, including age group, high school, collegiate, AAU, women, was a key factor in SJCC's high ranking in Northern California, and senior runners. The Running Review is available at many road races and track meets throughout Northern California for Some address changes for club members: Rene Yco has moved 25% an issue, or for $3-50 per year (first class mail). All to 1674 Adrian May, San Jose, 95122 (same phone); Sean O'Rior- West Valley TC athletes receive their copies free if their dues dan is now attending Washington State Univ. and has a new ad- are paid up for the year. dress of Neill Hall, %428, WSU, Pullman, Wash., 99163; Tony Ca sillas was inducted into the armed forces in February and can This paper's success depends on you, the readers, so please be reached (for a while anyway) by writing Pvt. Anthony Casillas, send us any pertinent information on the NorCal running scene (551-64-9872), Co. A BN2 BDE-1, Ft. -

6 World-Marathon-Majors1.Pdf

Table of contents World Marathon Majors World Marathon Majors: how it works ...............................................................................................................208 Scoring system .................................................................................................................................................................210 Series champions ............................................................................................................................................................211 Series schedule ................................................................................................................................................................213 2012-2013 Series results ..........................................................................................................................................214 2012-2013 Men’s leaderboard ...............................................................................................................................217 2012-2013 Women’s leaderboard ........................................................................................................................220 2013-2014 Men’s leaderboard ...............................................................................................................................223 2013-2014 Women’s leaderboard ........................................................................................................................225 Event histories ..................................................................................................................................................................227 -

Athletics 07 Krusty:Layout 1

2006 – 2007 Annual Report 2006–2007 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Company Information 1 Directors’ Profiles 2 Chairman’s Report 3 CEO’s Report 4 Directors’ Report 6 Statement of Financial Performance 9 Statement of Financial Position 10 Statement of Cash Flows 11 Notes to the Financial Statements 12 Independent Audit Report 17 Compilation Report 18 Detailed Profit and Loss 19 Competition Advisory Panel 20 Development Advisory Panel 22 Membership Advisory Panel 28 Marketing Advisory Panel 29 Officials Advisory Panel 30 ANSW Awards 31 Life Members 32 Merit Award Holders 32 Membership Statistics 34 Emerging Athlete Program 38 2005 – 2006 NSW Championships 43 NSW Roll of Honour 52 ATHLETICS NSW LIMITED (FOUNDED 20 APRIL, 1887, INCORPORATED 15 JANUARY, 1996) Postal Address: PO Box 595, Sydney Markets, NSW 2129 Street Address: Sydney Olympic Park Athletics Centre, Edwin Flack Drive, Sydney Olympic Park, NSW 2127 Telephone: (02) 9746 1122 Facsimile: (02) 9746 1168 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nswathletics.org.au COMPANY INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Officials John Patchett (Chairman) Peter Reynolds (Chair) Rob Blackadder Peter Bromley Graham Dwight Janelle Eldridge Elizabeth Miller Mary Fein Caroline Hall Betty Moore Neil Hinton Jill Huxley Phillip O’Hara Mary Macaluso Geoffrey Martin Michael O’Mara Andrew Matthews Heather Mitchell Gordon Windeyer Robert Mitchell Alan Mills Mark Rosenberg (Appointed 15 February, 2007) Anthony Okulicz Ron Richter STANDARDS COMMITTEE Membership Betty Moore David Archbold Andrew Matthews Les Carter Tim -

Updated 2019 Completemedia

April 15, 2019 Dear Members of the Media, On behalf of the Boston Athletic Association, principal sponsor John Hancock, and all of our sponsors and supporters, we welcome you to the City of Boston and the 123rd running of the Boston Marathon. As the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the Boston Marathon represents more than a 26.2-mile footrace. The roads from Hopkinton to Boston have served as a beacon for well over a century, bringing those from all backgrounds together to celebrate the pursuit of athletic excellence. From our early beginnings in 1897 through this year’s 123rd running, the Boston Marathon has been an annual tradition that is on full display every April near and far. We hope that all will be able to savor the spirit of the Boston Marathon, regardless whether you are an athlete or volunteer, spectator or member of the media. Race week will surely not disappoint. The race towards Boylston Street will continue to showcase some of the world’s best athletes. Fronting the charge on Marathon Monday will be a quartet of defending champions who persevered through some of the harshest weather conditions in race history twelve months ago. Desiree Linden, the determined and resilient American who snapped a 33-year USA winless streak in the women’s open division, returns with hopes of keeping her crown. Linden has said that last year’s race was the culmination of more than a decade of trying to tame the beast of Boston – a race course that rewards those who are both patient and daring. -

That Memorable First Marathon

THAT MEMORABLE FiR5T MARATHON BY ANTHONY TH. BijKERK AND PROF. DR. DAVID C. YOUNG. shall never see anything like it again" (Andrews). "[O]ne I, David Young, that it might be a good idea to collect them, 1 of the most extraordinary sights that I can remember. Its or at least most of the major English versions, and some Iimprint stays with me" (Coubertin, 1896). "Egad! The others as well, and make them available in a single volume, excitement and enthusiasm were simply indescribable” (F.). so that Olympic fans and scholars need not search piece- “What happened that moment. .cannot be described” meal through bibliographies and old journals in hopes of (Anninos). "[T]he whole scene can never be effaced from finding these sources. one’s memory. ..Such was the scene, unsurpassed and Not every one of these old journals is available in every unsurpassable. Who, who was present country nor has anything close to a there, does not wish that he may once “full” list of first-hand accounts of the again be permitted to behold it” WHAT HAD THE5E 1896 Games ever been published, (Robertson). although Bill Mallon and Ture What had these people seen? An PEOPLE sEEN? Widlund’s latest publication titled: THE epiphany? Fish multiplying? No. They AN EPIPHANY? 1896 OLYMPIC GAMES (published in had seen Spyros Louis. They had seen FISH MULTIPLYING? 1998) comes very close. No scholar has the finish of the worlds first Marathon, NO. THEY HAD SEEN yet based an account of IOC Olympiad I the highlight-the climax, three days sPYROs LOUis. -

Inspiring Quotes About Running

Inspiring Quotes about Running “My feeling is that any day I am too busy to run is a day that I am too busy.” --John Bryant “Struggling and suffering are the essence of a life worth living. If you're not pushing yourself beyond the comfort zone, if you're not demanding more from yourself - expanding and learning as you go - you're choosing a numb existence. You're denying yourself an extraordinary trip.” --Dean Karnazes “The five S's of sports training are: Stamina, Speed, Strength, Skill and Spirit; but the greatest of these is Spirit.” --Ken Doherty “You have a choice. You can throw in the towel, or you can use it to wipe the sweat off of your face.” --Gatorade “Once you're beat mentally, you might as well not even go to the starting line.” --Todd Williams "What the years have shown me is that running clarifies the thinking process as well as purifies the body. I think best—most broadly and fully—when I am running." --Amby Burfoot “A man can fail many times, but he isn't a failure until he begins to blame somebody else.” --Steve Prefontain "The will to win is worthless, without the will to prepare." --Thane Yost www.marathontrainingacademy.com Page 1 “Life’s battles don't always go to the strongest or fastest man, but sooner or later the man who wins is the fellow who thinks he can.” --Steve Prefontain "You don't stop running because you get old, you get old because you stop running." --Christopher McDougall "No one ever drowned in sweat. -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Norcal Running Review Is Published on a Monthly Basis by the West Valley Track Club

the athletic department RUNNING UNLIMITED JOHN KAVENY ON THE COVER West Valley Track Club's Jim Dare dur ing the final mile (4:35.8), his 30th, in the Runner's World sponsored 24-Hr Relay at San Jose State. Dare's aver age for his 30 miles was 4:47.2, and he led his teammates to a new U.S. Club Record of 284 miles, 224 yards, break ing the old mark, set in 1972 by Tulsa Running Club, by sane nine miles. Full results on pages 17-18. /Wayne Glusker/ STAFF EDITOR: Jack Leydig; PRINTER: Frank Cunningham; PHOTOGRA PHERS: John Marconi, Dave Stock, Wayne Glusker; NOR-CAL PORTRAIT CONTENTS : Jon Hendershott; COACH'S CORNER: John Marconi; WEST VALLEY PORTRAIT: Harold DeMoss; NCRR POINT RACE: Art Dudley; Readers' Poll 3 West Valley Portrait 10 WOMEN: Roxy Andersen, Harmon Brown, Jim Hume, Vince Reel, Dawn This & That 4 Special Articles 10 Bressie; SENIORS: John Hill, Emmett Smith, George Ker, Todd Fer NCRR LDR Point Ratings 5 Scheduling Section 12 guson, David Pain; RACE WALKING: Steve Lund; COLLEGIATE: Jon Club News 6 Race Walking News 14 Hendershott, John Sheehan, Fred Baer; HIGH SCHOOL: Roy Kissin, Classified Ads 8 Track & Field Results 14 Dave Stock, Mike Ruffatto; AAU RESULTS: Jack Leydig, John Bren- Letters to the Editor 8 Road Racing Results 16 nand, Bill Cockerham, Jon Hendershott. --- We always have room for Coach's Comer 9 Late News 23 more help on our staff, especially in the high school and colle NorCal Portrait 9 giate areas, now that cross country season has begun. -

(Editor).Indd 4 7/23/17 15:15

Track & Field News The Bible Of The Sport Since 1948 from the Founded by Bert & Cordner Nelson E. GARRY HILL — Editor ED FOX — Publisher editor EDITORIAL STAFF Sieg Lindstrom ..........Managing Editor Jeff Hollobaugh .......... Associate Editor BUSINESS STAFF Janet Vitu ..............Executive Publisher BACK IN JANUARY OF 2014 this space was dedicated to the concept “Te IAAF & USATF Halls Of Fame Need More Members.” Wallace Dere .................Offce Manager What was true then has become even truer today, but in this column I’ll just talk about the Teresa Tam ......................... Art Director more important of the two Halls, the IAAF’s, which hasn’t been well handled from the get-go, WORLD RANKINGS COMPILERS and almost 5 years after its inaugural class Jonathan Berenbom, Richard Hymans, Dave was inducted still numbers a mere 48 (31 The IAAF’s Hall Of Fame Johnson, Nejat Kök, R.L. Quercetani (Emeritus) men, 17 women). Still Doesn’t Have Nearly How we got to those 48 still gripes me. SENIOR EDITORS When the IAAF did its inaugural class of Bob Bowman (Walking), Roy Conrad (Special Projects), Jon Hendershott (Emeritus), Bob Hersh Enough Members 24 in November of ’12, it ensured that all (Eastern), Mike Kennedy (HS Girls), Glen Mc- geographical areas and all event groups were Micken (Lists), Walt Murphy (Relays), Jim Rorick represented. Tat’s wonderfully PC and even (Stats), Jack Shepard (HS Boys) makes some decent marketing sense, but it ofends my sense of what a HOF is all about. And what the frst class named is all about, which is the honor of being super-special.