High Performance Seminar 2009 World Half Marathon Championships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

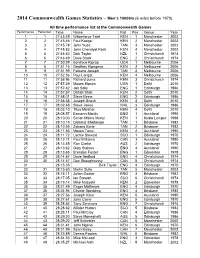

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

Marathon Calendar the Best Races to Run Expert Advice Product Reviews

MARATHON GUIDE 2018 THE BEST RACES TO RUN MARATHON CALENDAR PRODUCT REVIEWS EXPERT ADVICE CHOOSE YOUR NEXT 26.2-MILE CHALLENGE 1 Marathon cover.indd 1 04/11/2017 11:49 MARATHON GUIDE 2018 WELCOME AND CONTENTS @ATHLETICSWEEKLY TAKE CONTENTS 4 WHY RUN A YOUR PICK SHUTTERSTOCK MARATHON? The lure of 26.2 miles DECISIONS, decisions. When it comes to choice, marathon runners really have never 6 EXPERT ADVICE had it so good. Those in the know pass on Such has been the explosion in mass their running wisdom participation running that it can now feel at times like there is barely a corner of the 10 YOUR EVENTS planet which doesn’t have its own GUIDE STARTS HERE 26.2-mile event. Whether you are planning your first We examine an extensive range marathon or you’re an experienced of marathon events for your campaigner clocking up yet more miles, consideration the choice of the race for which you are planning to part with your hard-earned entry fee can quite rightly take a lot of time and consideration. Options abound and, as the winter begins to draw in and thoughts turn towards targets for 2018, we at Athletics Weekly have been busy putting together this 32-page marathon guide which is packed with running possibilities. From sunny Cyprus to the heart of Scotland, there is information on a wide range of marathons for you to consider, whether they be taking place in spring, 16 RACE CALENDAR summer, autumn or indeed the depths of Marathon choices for 2018 winter next year. -

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

Hall of Fame

scottishathletics HALL OF FAME 2018 October A scottishathletics history publication Hall of Fame 1 Date: CONTENTS Introduction 2 Jim Alder, Rosemary Chrimes, Duncan Clark 3 Dale Greig, Wyndham Halswelle 4 Eric Liddell 5 Liz McColgan, Lee McConnell 6 Tom McKean, Angela Mudge 7 Yvonne Murray, Tom Nicolson 8 Geoff Parsons, Alan Paterson 9 Donald Ritchie, Margaret Ritchie 10 Ian Stewart, Lachie Stewart 11 Rosemary Stirling, Allan Wells 12 James Wilson, Duncan Wright 13 Cover photo – Allan Wells and Patricia Russell, the daughter of Eric Liddell, presented with their Hall of Fame awards as the first inductees into the scottishathletics Hall of Fame (photo credit: Gordon Gillespie). Hall of Fame 1 INTRODUCTION The scottishathletics Hall of Fame was launched at the Track and Field Championships in August 2005. Olympic gold medallists Allan Wells and Eric Liddell were the inaugural inductees to the scottishathletics Hall of Fame. Wells, the 1980 Olympic 100 metres gold medallist, was there in person to accept the award, as was Patricia Russell, the daughter of Liddell, whose triumph in the 400 metres at the 1924 Olympic Games was an inspiration behind the Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire. The legendary duo were nominated by a specially-appointed panel consisting of Andy Vince, Joan Watt and Bill Walker of scottishathletics, Mark Hollinshead, Managing Director of Sunday Mail and an on-line poll conducted via the scottishathletics website. The on-line poll resulted in the following votes: 31% voting for Allan Wells, 24% for Eric Liddell and 19% for Liz McColgan. Liz was inducted into the Hall of Fame the following year, along with the Olympic gold medallist Wyndham Halswelle. -

Welcome WHAT IS IT ABOUT GOLF? EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN

EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN HEADLAND James Watson and Steve Crosdale, both former side of the business, as well as the practical. greenkeepers with a total of 24 years experience in "This position provides the ideal opportunity to the industry behind them, join Headland Amenity concentrate on this area and help customers as Regional Technical Managers. achieve the best possible results from a technical Welcome James has responsibility for South East England, perspective," he said. including South London, Surrey, Sussex and Kent, James, whose father retired as a Course while Steve Crosdale takes East Anglia and North Manager in December, and who practised the London including Essex, profession himself for 14 years before moving into WHAT IS IT Hertfordshire and sales a year ago, says that he needed a new ABOUT GOLF? Cambridgeshire. challenge but wanted something where he could As I write the BBC are running a series of Andy Russell, use his experience built programmes in conjunction with the 50th Headland's Sales and up on golf courses anniversary of their Sports Personality of the Year Marketing Director said around Europe. Award with a view to identifying who is the Best of that the creation of these "This way I could the Best. two new posts is take a leap of faith but I Most sports are represented. Football by Bobby indicative of the way the didn't have to leap too Moore, Paul Gascoigne, Michael Owen and David company is growing. Beckham. Not, surprisingly, by George Best, who was James Watson far," he explains. "I'm beaten into second place by Princess Anne one year. -

MEDIA INFO & Fast Facts

MEDIAWELCOME INFO MEDIA INFO Media Info & FAST FacTS Media Schedule of Events .........................................................................................................................................4 Fact Sheet ..................................................................................................................................................................6 Prize Purses ...............................................................................................................................................................8 By the Numbers .........................................................................................................................................................9 Runner Pace Chart ..................................................................................................................................................10 Finishers by Year, Gender ........................................................................................................................................11 Race Day Temperatures ..........................................................................................................................................12 ChevronHoustonMarathon.com 3 MEDIA INFO Media Schedule of Events Race Week Press Headquarters George R. Brown Convention Center (GRB) Hall D, Third Floor 1001 Avenida de las Americas, Downtown Houston, 77010 Phone: 713-853-8407 (during hours of operation only Jan. 11-15) Email: [email protected] Twitter: @HMCPressCenter -

Official Journal of the British Milers' Club

Official Journal of the British Milers’ Club VOLUME 3 ISSUE 14 AUTUMN 2002 The British Milers’ Club Contents . Sponsored by NIKE Founded 1963 Chairmans Notes . 1 NATIONAL COMMITTEE President Lt. CoI. Glen Grant, Optimum Speed Distribution in 800m and Training Implications C/O Army AAA, Aldershot, Hants by Kevin Predergast . 1 Chairman Dr. Norman Poole, 23 Burnside, Hale Barns WA15 0SG An Altitude Adventure in Ethiopia by Matt Smith . 5 Vice Chairman Matthew Fraser Moat, Ripple Court, Ripple CT14 8HX End of “Pereodization” In The Training of High Performance Sport National Secretary Dennis Webster, 9 Bucks Avenue, by Yuri Verhoshansky . 7 Watford WD19 4AP Treasurer Pat Fitzgerald, 47 Station Road, A Coach’s Vision of Olympic Glory by Derek Parker . 10 Cowley UB8 3AB Membership Secretary Rod Lock, 23 Atherley Court, About the Specificity of Endurance Training by Ants Nurmekivi . 11 Upper Shirley SO15 7WG BMC Rankings 2002 . 23 BMC News Editor Les Crouch, Gentle Murmurs, Woodside, Wenvoe CF5 6EU BMC Website Dr. Tim Grose, 17 Old Claygate Lane, Claygate KT10 0ER 2001 REGIONAL SECRETARIES Coaching Frank Horwill, 4 Capstan House, Glengarnock Avenue, E14 3DF North West Mike Harris, 4 Bruntwood Avenue, Heald Green SK8 3RU North East (Under 20s)David Lowes, 2 Egglestone Close, Newton Hall DH1 5XR North East (Over 20s) Phil Hayes, 8 Lytham Close, Shotley Bridge DH8 5XZ Midlands Maurice Millington, 75 Manor Road, Burntwood WS7 8TR Eastern Counties Philip O’Dell, 6 Denton Close, Kempston MK Southern Ray Thompson, 54 Coulsdon Rise, Coulsdon CR3 2SB South West Mike Down, 10 Clifton Down Mansions, 12 Upper Belgrave Road, Bristol BS8 2XJ South West Chris Wooldridge, 37 Chynowen Parc, GRAND PRIX PRIZES (Devon and Cornwall) Cubert TR8 5RD A new prize structure is to be introduced for the 2002 Nike Grand Prix Series, which will increase Scotland Messrs Chris Robison and the amount that athletes can win in the 800m and 1500m races if they run particular target times. -

10000 Meters

2020 Olympic Games Statistics - Women’s 10000m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) Kenyan woman never won the W10000m in the OG. Will H Obiri be the first? 2) Showdown between Hassan & Gidey. Can Hassan become first from NED to win the Olympic 10000m? 3) Can Tsehay Gemechu become second (after Tulu) All African Games champion to win the Olympics. 4) Can Gezahegne win first medal for BRN? 5) Can Eilish McColgan become second GBR runner (after Liz, her mother) to win an Olympic medal? Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 29:17.45 Almaz Ayana ETH 1 Rio de Janeiro 2016 2 2 29:32.53 Vivian Cheruiyot KEN 2 Rio de Jane iro 2016 3 3 29:42.56 Tirunesh Dibaba ETH 3 Rio de Janeiro 2016 4 4 29:53.51 Al ice Aprot Nawowuna KEN 4 Rio de Janeiro 2016 5 29:54.66 Tirunesh Dibaba ETH 1 Beijing 2008 6 5 30:07.78 Betsy Sa ina KE N 5 Rio de Jane iro 2016 7 6 30 :13.17 Molly Huddle USA 6 Rio de Jan eiro 2016 8 7 30:17.49 Derartu Tulu ETH 1 Sydney 2000 Slowest winning time: 31:06.02 by Derartu Tulu (ETH) in 1992 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 15.08 29:17.45 Alm az Ayana ETH Rio de Janeiro 2016 5.73 31:06.02 Derartu Tulu ETH Barcelona 1992 Min 0.62 30:24.36 Xing Huina CHN Athinai 2004 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 29:17.45 Almaz Ayana ETH Rio de Janeiro 2016 29:54.66 Ti runesh Dibaba ETH Beijing 2008 2 29:32.53 Vivian Cheruiyot KEN Rio de Janeiro 2016 30:22.22 Shalane Flanagan USA Beijing 2008 -

Norcal Running Review

The Northern California Running Review, formerly the West Ramirez. Juan is a freshman at San Jose City College and lives Valley Newsletter. is published on a monthly basis by the West at 64.6 Jackson Ave., San Jose, 95116 (Apt. 9) - Ph. 258-9865. Valley Track Club of San Jose, California. It is a communica- At 19, Juan has best times of 1:59.7, 4:28.3, and 9:51.7. He tion medium for all Northern California track and field ath- ran 19:45 for four miles cross country this past season, and letes, including age group, high school, collegiate, AAU, women, was a key factor in SJCC's high ranking in Northern California, and senior runners. The Running Review is available at many road races and track meets throughout Northern California for Some address changes for club members: Rene Yco has moved 25% an issue, or for $3-50 per year (first class mail). All to 1674 Adrian May, San Jose, 95122 (same phone); Sean O'Rior- West Valley TC athletes receive their copies free if their dues dan is now attending Washington State Univ. and has a new ad- are paid up for the year. dress of Neill Hall, %428, WSU, Pullman, Wash., 99163; Tony Ca sillas was inducted into the armed forces in February and can This paper's success depends on you, the readers, so please be reached (for a while anyway) by writing Pvt. Anthony Casillas, send us any pertinent information on the NorCal running scene (551-64-9872), Co. A BN2 BDE-1, Ft. -

Updated 2019 Completemedia

April 15, 2019 Dear Members of the Media, On behalf of the Boston Athletic Association, principal sponsor John Hancock, and all of our sponsors and supporters, we welcome you to the City of Boston and the 123rd running of the Boston Marathon. As the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the Boston Marathon represents more than a 26.2-mile footrace. The roads from Hopkinton to Boston have served as a beacon for well over a century, bringing those from all backgrounds together to celebrate the pursuit of athletic excellence. From our early beginnings in 1897 through this year’s 123rd running, the Boston Marathon has been an annual tradition that is on full display every April near and far. We hope that all will be able to savor the spirit of the Boston Marathon, regardless whether you are an athlete or volunteer, spectator or member of the media. Race week will surely not disappoint. The race towards Boylston Street will continue to showcase some of the world’s best athletes. Fronting the charge on Marathon Monday will be a quartet of defending champions who persevered through some of the harshest weather conditions in race history twelve months ago. Desiree Linden, the determined and resilient American who snapped a 33-year USA winless streak in the women’s open division, returns with hopes of keeping her crown. Linden has said that last year’s race was the culmination of more than a decade of trying to tame the beast of Boston – a race course that rewards those who are both patient and daring. -

NUTS NOTES Vol

NUTS NOTES Vol. 18 No.3 June 1980 Editor: Tim Lynch-Staunton, Meadowbank, Eydens Avenue, Walton-on-Thamee, Surrey KT12 3 JP. This is the third issue of NUTS NOTES to go on sale to the general public* For the last twenty or so years it has been available to members of the NUTS on a quarterly basis, thanks mainly to the untiring efforts of Andrew Huxtable, who was editor for many years until last year. We hope this issue will be of interest to athletics fans, in particular those who like athletics' statistics, although it will not in future be entirely a statistical newsletter, and will encourage those who compile lists and other data for their own amusement to submit compilations for consideration for inclusion in future issues. T.L-S. BRITISH BEST PERFORMANCES OF ALL-TIME - 10 MILES (ROAD) One of the most frequently contested yet least documented distance events is the 10 miles. So far as I am aware, no one has previously attempted to produce an all- time list for road performances. There are, of course, certain inherent problems. It's an event which, like the marathon, is subject to considerable variation in the severity of courses; and it is sometimes difficult to establish for sure the accuracy of distance for races advertised as being at 10 miles. But there are several very good reasons for establishing a statistical record of the event. First, almost all top-class distance-runners contest it during their career. Second, it brings together trackmen, cross-country runners and marathoners. Third, it has also produced a significant number of performers who have not achieved major recognition in other events. -

'The Greatest Feat in the History of British Athletics.'

THE LONDON 2012 OLYMPIC GAMES 73 Iguider and Kenya’s Thomas Pkemei Longosiwa. Left: Determination. Mo Farah runs There was a time when Farah would have been through the pain on his way to winning his second gold medal of swallowed up by men such as these, but not now. the London 2012 Olympic Games The Briton pressed harder on the accelerator and in the 5,000m final. found more speed, his face showing his effort and sheer desperation to get to the finish line first. The nearer it came, the less serious their gold medal challenge appeared. Even before he crossed the line, to a standing ovation from the Stadium crowd, Farah’s unforgettable celebrations had begun. His hands first crossed and then stretched wide as his mouth 110m Hurdles gold opened and the reality hit home. He had run falls to USA the last mile in four minutes and the last lap in Top-ranked American Aries Merritt won the 110m 52.94 seconds, contributing to an overall time Hurdles in what was a of 13:41.66. Ethiopian Dejen Gebremeskel took competition littered with silver with 13:41.98 and Longosiwa of Kenya injuries and falls. Among the casualties were the Chinese bronze with 13:42.36. superstar and Athens 2004 champion Xiang Lui, who succumbed to an Achilles tendon injury just as he had done at Beijing 2008. The final also saw world record holder Dayron Robles pull up injured. ‘The greatest feat in the history of British athletics.’ Brendan Foster, 10,000m Olympic bronze medallist at Montreal 1976, acknowledges the scale of Mo Farah’s achievement One day like this.