CHAPTER ONE Introduction.Docx.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres Chirumhanzu District Team 1 Ward Centre Dates 18 Mwire primary school 10/06/13-11/06/13 18 Tokwe 4 clinic 12/06/13-13/06/13 18 Chingegomo primary school 14/06/13-15/06/13 16 Chishuku Seondary school 16/06/13-18/06/13 9 Upfumba Secondary school 19/06/13-21/06/13 3 Mutya primary school 22/06/13-24/06/13 2 Gonawapotera secondary school 25/06/13-27/06/13 20 Wildegroove primary school 28/06/13-29/06/13 15 Kushinga primary school 30/06/13-02/07/13 12 Huchu compound 03/07/13-04/-07/13 12 Central estates HQ 5/7/13 20 Mtao/Fair Field compound 6/7/13 12 Chiudza homestead 07/07/13-08/06/13 14 Njerere primary school 9/7/13 Team 2 Ward Centre Dates 22 Hillview Secondary school 10/07/13-12/07/13 17 Lalapanzi Secondary school 13/07/13-15/07/13 16 Makuti homestead 16/06/13-17/06/13 1 Mapiravana Secondary school 18/06/13-19/06/13 9 Siyahukwe Secondary school 20/06/13-23/06/13 4 Chizvinire primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 21 Mukomberana Seconadry school 26/06/13-29/06/13 20 Union primary school 30/06/13-01/07/13 15 Nyikavanhu primary school 02/07/13-03/07/13 19 Musens primary school 04/07/13-06/07/13 16 Utah primary school 07/7/13-09/07/13 Team 3 Ward Centre Dates 11 Faerdan primary school 10/07/13-11/07/13 11 Chamakanda Secondary school 12/07/13-14/07/13 11 Chamakanda primary school 15/07/13-16/07/13 5 Chizhou Secondary school 17/06/13-16/06/13 3 Chilimanzi primary school 21/06/13-23/06/13 25 Maponda primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 6 Holy Cross seconadry school 26/06/13-28/06/13 20 New England Secondary -

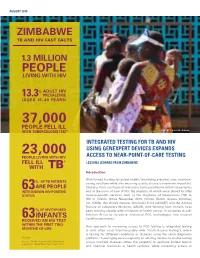

Integrated Testing for TB and HIV Zimbabwe

AUGUST 2019 ZIMBABWE TB AND HIV FAST FACTS 1.3 MILLION PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV % ADULT HIV 13.3 PREVALENCE (AGES 15–49 YEARS) 37,000 PEOPLE FELL ILL WITH TUBERCULOSIS (TB)* © UNICEF/Costa/Zimbabwe INTEGRATED TESTING FOR TB AND HIV 23,000 USING GENEXPERT DEVICES EXPANDS PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV ACCESS TO NEAR-POINT-OF-CARE TESTING FELL ILL * LESSONS LEARNED FROM ZIMBABWE WITH TB Introduction With limited funding for global health, identifying practical, cost- and time- OF TB PATIENTS % saving solutions while also ensuring quality of care is evermore important. 63ARE PEOPLE Globally, there are fleets of molecular testing platforms within laboratories WITH KNOWN HIV-POSITIVE and at the point of care (POC), the majority of which were placed to offer STATUS disease-specific services such as the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) or HIV in infants. Since November 2015, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Inc. (CHAI), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM), with funding from Unitaid, have % OF HIV-EXPOSED been working closely with ministries of health across 10 countries in sub- Saharan Africa to introduce innovative POC technologies into national INFANTS 1 63 health programmes. RECEIVED AN HIV TEST WITHIN THE FIRST TWO One approach to increasing access to POC testing is integrated testing MONTHS OF LIFE (a term often used interchangeably with “multi-disease testing”), which is testing for different conditions or diseases using the same diagnostic *Annually platform.2 Leveraging excess capacity on existing devices to enable testing Sources: UNAIDS estimates 2019; World Health across multiple diseases offers the potential to optimize limited human Organization, ‘Global Tuberculosis Report 2018’ and financial resources at health facilities, while increasing access to rapid testing services. -

Final Report

Conserving Our Land, Producing our Food – Sustainable Management of Land and Forests in Malawi & Zimbabwe “An evaluation of the Zimbabwe program component” FINAL REPORT Conservation Agriculture Farmer in Zvimba (Fieldwork Picture) Prepared by April 2015 “Conserving Our Land, Producing our Food – Sustainable Management of Land and Forests in Malawi & Zimbabwe” External Independent End of Term Evaluation Final Report – April 2015 DISCLAIMER This evaluation was commissioned by the Progressio / CIIR and independently executed by Taonabiz Consulting. The views and opinions expressed in this and other reports produced as part of this evaluation are those of the consultants and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Progressio, its implementing partner Environment Africa or its funder Big Lottery. The consultants take full responsibility for any errors and omissions which may be in this document. Evaluation Team Dr Chris Nyakanda / Agroforestry Expert Mr Tawanda Mutyambizi / Agribusiness Expert P a g e | i “Conserving Our Land, Producing our Food – Sustainable Management of Land and Forests in Malawi & Zimbabwe” External Independent End of Term Evaluation Final Report – April 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS On behalf of the Taonabiz consulting team, I wish to extend my gratitude to all the people who have made this report possible. First and foremost, I am grateful to the Progressio and Environment Africa staff for their kind cooperation in providing information as well as arranging meetings for field visits and national level consultations. Special thanks go to Patisiwe Zaba the Progressio Programme Officer and Dereck Nyamhunga Environment Africa M&E Officer for scheduling interviews. We are particularly indebted to the officials from the Local Government Authorities, AGRITEX, EMA, Forestry Commission and District Councils who made themselves readily available for discussion and shared their insightful views on the project. -

The Agrarian Question in Tanzania?

The Agrarian Question In Tanzania? CurrenT AfrICAn Issues 45 THe AGrArIAn QUESTIOn In TAnZAnIA? A state of the Art Paper sam Maghimbi razack B. Lokina Mathew A. senga nOrDIsKA AfrIKAInsTITuTeT, uPPsALA In coperation with THe unIVersITY Of DAr ES sALAAM 2 011 1 sam Maghimbi, razack B. Lokina, Mathew A. senga The Mwalimu Nyerere Professorial Chair in Pan-African Studies was established as a university chair at the University of Dar es Salaam in honour of the great nationalist and pan-Africanist leader of Africa and the first president of Tanzania, Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere. It was inaugurated on April 19, 2008 by the Prime Minister Honourable Mizengo Pinda in the presence of Mama Maria Nyerere. The main objective of the Chair is to reinvigorate intellectual debates on the Campus and stimulate basic research on burning issues facing the country and the continent from a pan-African perspective. The core activities of the Chair include publication of state of the art papers. As part of the latter, the Chair is pleased to publish the first paper The Agrarian Question in Tanzania. It is planned to publish at least one state of the art paper every year. first published by Mwalimu Nyerere Professorial Chair in Pan-African Studies University of Dar es Salaam P. O. Box 35091 Dar es Salaam Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nyererechair.udsm.ac.tz INDExING TErMS: Agrarian policy Agrarian structure Peasantry Agricultural population Land tenure State Agrarian reform Land reform rural development Economic and social development Tanzania The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. -

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

And Colin Bundy's “African Peasantry”

International Journal of Development and Sustainability ISSN: 2186-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 3 Number 7 (2014): Pages 1410-1437 ISDS Article ID: IJDS14042304 Chayanov’s “development theory” and Colin Bundy’s “African peasantry”: Relevance to contemporary development and agricultural discourse Anis Mahomed Karodia* Regent Business School, Durban, South Africa Abstract of Part One This paper attempts to look at the work of Chayanov, in respect of contemporary development issues and reexamines his work (on the basis of the work of TeodorShanin and partly by HamzaAlavi). Chayanov was considered during his time as the new Marx. His discourse and thoughts were fashioned upon the political economy and based on intellectual criticism of the USSR. He was sidelined by the then USSR and put to pasture by the many forms of repression in the then Soviet Union. His work bears utmost relevance to contemporary dialogue in respect of agriculture and development issues, in the context of the modern world. On the other hand the second part of the paper will look at Colin Bundy’s book the Rise and Fall of the African Peasantry. It is probably the most influential account of rural history produced in the 1970’s, and is hailed as a major reinterpretation of South African history, in terms of African agriculture which was considered as inherently primitive or backward and capitalism was hostile to peasants. Both parts of the paper look at the preface of the books written by TeodorShanin and By Colin Bundy himself, in order to look at very important and vexing issues that permeate 21st century discourse on development and agriculture Keywords:Development; Agriculture; Peasantry; Reinterpretation; Political Economy; Contemporary Dialogue; Capitalism; Poverty; Legacy; Traditionalism. -

2021 Rural Livelihoods Assessment Masvingo Province Report

Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) 2021 Rural Livelihoods Assessment Masvingo Province Report ZimVAC is Coordinated By Food And Nutrition Council (FNC) Housed At SIRDC: 1574 Alpes Rd, Hatcliffe, Harare. Tel: +263 242 862 586/862 025 Website: www.fnc.org.zw Email: [email protected] Twitter: @FNCZimbabwe Instagram: fnc_zim Facebook: @FNCZimbabwe 1 Foreword In its endeavour to ‘promote and ensure adequate food and nutrition security for all people at all times’, the Government of Zimbabwe continues to exhibit its commitment towards reducing food and nutrition insecurity, poverty and improving livelihoods amongst the vulnerable populations in Zimbabwe through operationalization of Commitment 6 of the Food and Nutrition Security Policy (FNSP). Under the coordination of the Food and Nutrition Council, the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) undertook the 2021 Rural Livelihoods Assessment, the 21st since its inception. ZimVAC is a technical advisory committee comprised of representatives from Government, Development Partners, UN, NGOs, Technical Agencies and the Academia. Through its assessments, ZimVAC continues to collect, synthesize and disseminate high quality information on the food and nutrition security situation in a timely manner. The 2021 RLA was motivated by the need to provide credible and timely data to inform progress of commitments in the National Development Strategy 1 (NDS 1) and inform planning for targeted interventions to help the vulnerable people in both their short and long-term vulnerability context. Furthermore, as the ‘new normal’ under COVID-19 remains fluid and dynamic, characterized by a high degree of uncertainty, the assessment sought to provide up to date information on how rural food systems and livelihoods have been impacted by the pandemic. -

PLAAS RR46 Smeadzim 1.Pdf

Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Report 46 Space, Markets and Employment in Agricultural Development: Zimbabwe Country Report Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Published by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Email: [email protected] Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research Report no. 46 June 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher or the authors. Copy Editor: Vaun Cornell Series Editor: Rebecca Pointer Photographs: Pamela Ngwenya Typeset in Frutiger Thanks to the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) and the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Growth Research Programme Contents List of tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................. iii Acronyms and abbreviations ...................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ -

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe ZWE38611 Farmers Bikita/Masvingo MDC/ZANU-PF 3 May 2011

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe ZWE38611 Farmers Bikita/Masvingo MDC/ZANU-PF 3 May 2011 1. Is there any country information about attacks on farmers in the in Bikita in the district of Masvingo, in April 2008? Sources indicate that attacks took place on farmers in the Masvingo district during April 2008. These attacks coincided with national elections when tension between government and opposition supporters was extremely high. According to a Times Online report from 8 April he farm invasions began on Saturday in Masvingo province, about 160 miles south of the capital, Harare. Five farmers were forced to flee or were trapped inside their homes by drunken mo 1 The same report stated that two farm owners had been forced from their land for voting for the MDC, and farmers and their staff were beaten and threatened with further violence.2 The MDC claimed on 18 April 2008 that the violence started almost immediately after the elections on March 29, and claimed some of its supporters in remote rural areas were homeless after their homes were looted and burnt down by the suspected ZANU PF (Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front) activists.3 The US Ambassador to Zimbabwe James McGee on 18 April commented on the violence taking place through Zimbabwe: There is growing evidence that rural communities are being punished for their support for opposition candidates. We have disturbing and confirmed reports of threats, beatings, abductions, burning of homes and even murder, from many parts of the country.4 These activities formed part of Operation Mavhoterapapi (who/where did you vote), a campaign designed to intimidate MDC supporters, and centred on rural areas of Zimbabwe. -

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This Book Is a Product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This book is a product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network. Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin Edited by Mzime Ndebele-Murisa Ismael Aaron Kimirei Chipo Plaxedes Mubaya Taurai Bere Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa DAKAR © CODESRIA 2020 Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop, Angle Canal IV BP 3304 Dakar, 18524, Senegal Website: www.codesria.org ISBN: 978-2-86978-713-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission from CODESRIA. Typesetting: CODESRIA Graphics and Cover Design: Masumbuko Semba Distributed in Africa by CODESRIA Distributed elsewhere by African Books Collective, Oxford, UK Website: www.africanbookscollective.com The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisation whose principal objectives are to facilitate research, promote research-based publishing and create multiple forums for critical thinking and exchange of views among African researchers. All these are aimed at reducing the fragmentation of research in the continent through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguistic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes Africa Development, the longest standing Africa based social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; Africa Review of Books and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. The Council also co- publishes Identity, Culture and Politics: An Afro-Asian Dialogue; and the Afro-Arab Selections for Social Sciences. -

Latin America

Latin America JOHN GLEDHILL, The University of Manchester ‘Latin’ America is a region constructed in a context of imperial rivalries and disputes about how to build ‘modern’ nations that made it an ‘other America’ distinct from ‘Anglo’ America. Bringing together people without previous historical contact, the diversity of its societies and cultures was increased by the transatlantic slave trade and later global immigration. Building on the constructive relationship that characterises the ties between socio-cultural anthropology and history in the region today, this entry discusses differences in colonial relations and cultural interaction between European, indigenous, and Afro-Latin American people in different countries and the role of anthropologists in nation-building projects that aimed to construct national identities around ‘mixing’. It shows how anthropologists came to emphasise the active role of subordinated social groups in making Latin America’s ‘new peoples’. Widespread agrarian conflicts and land reforms produced debates about the future of peasant farmers, but new forms of capitalist development, growing urbanisation, and counter-insurgency wars led to an era in which indigenous identities were reasserted and states shifted towards a multicultural politics that also fostered Afro-Latin American movements. Anthropology has enhanced understanding of the diversity, complexity, and contradictions of these processes. Latin American cities are characterised by stark social inequalities, but anthropologists critiqued the stigmatisation