Introduction to Wood Species and Grading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Properties of Western Larch and Their Relation to Uses of the Wood

TECHNICAL BULLETIN NO. 285 MARCH, 1932 PROPERTIES OF WESTERN LARCH AND THEIR RELATION TO USES OF THE WOOD BY R. P. A. JOHNSON Engineer, Forest Products Laboratory AND M. I. BRADNER In Charge^ Office of Forest Products y Region I Branch of Research, Forest Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, WASHINGTON, D. C. TECHNICAL BULLETIN NO. 285 MARCH, 1932 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE WASHINGTON, D. C. PROPERTIES OF WESTERN LARCH AND THEIR RELATION TO USES OF THE WOOD By R. P. A. JOHNSON, Engineer, Forest Products Laboratory^^ and M. I. BRADNER, in Charge, Office of Forest Products, Region 1, Branch of Research, Forest Service * CONTENTS Page Page Introduction 1 Mechanical and physical properties—Con. The larch-fir mixture 2 Resistance to decay, weathering, and Character and range of the western larch insects 39 forest __ 4 Reaction to preservative treatment 42 Occurrence 4 Heat and insulating properties 42 Character 4 Permeability by liquids 42 Size of stand 7 Tendency to impart odor or ñavor___:. _. 43 Cut and supply 9 Tendency to leach or exude extractives. _ 43 Merchandising practices 10 Chemical properties 43 distribution lO Fire resistance ., 43 Percentage of cut going into various lum- Characteristic defects of western larch 44 ber items 12 Natural defects 44 Descriptive properties of western larch 13 Seasoning defects 46 General description of the wood 13 Manufacturing defects 47 Heartwood content of lumber 13 Grades and their characteristics 47 Growth rings 14 Grade yield and production 48 Summer-wood content 14 Heartwood content 50 Figure. 14 Width of rings 50 How to distinguish western larch from other Grade descriptions . -

Western Larch, Which Is the Largest of the American Larches, Occurs Throughout the Forests of West- Ern Montana, Northern Idaho, and East- Ern Washington and Oregon

Forest An American Wood Service Western United States Department of Agriculture Larch FS-243 The spectacular western larch, which is the largest of the American larches, occurs throughout the forests of west- ern Montana, northern Idaho, and east- ern Washington and Oregon. Western larch wood ranks among the strongest of the softwoods. It is especially suited for construction purposes and is exten- sively used in the manufacture of lumber and plywood. The species has also been used for poles. Water-soluble gums, readily extracted from the wood chips, are used in the printing and pharmaceutical industries. F–522053 An American Wood Western Larch (Lark occidentalis Nutt.) David P. Lowery1 Distribution Western larch grows in the upper Co- lumbia River Basin of southeastern British Columbia, northeastern Wash- ington, northwest Montana, and north- ern and west-central Idaho. It also grows on the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and north- central Oregon and in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains of southeast Wash- ington and northeast Oregon (fig. 1). Western larch grows best in the cool climates of mountain slopes and valleys on deep porous soils that may be grav- elly, sandy, or loamy in texture. The largest trees grow in western Montana and northern Idaho. Western larch characteristically occu- pies northerly exposures, valley bot- toms, benches, and rolling topography. It occurs at elevations of from 2,000 to 5,500 feet in the northern part of its range and up to 7,000 feet in the south- ern part of its range. The species some- times grows in nearly pure stands, but is most often found in association with other northern Rocky Mountain con- ifers. -

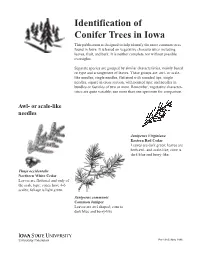

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

Douglasfirdouglasfirfacts About

DouglasFirDouglasFirfacts about Douglas Fir, a distinctive North American tree growing in all states from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, is probably used for more Beams and Stringers as well as Posts and Timber grades include lumber and lumber product purposes than any other individual species Select Structural, Construction, Standard and Utility. Light Framing grown on the American Continent. lumber is divided into Select Structural, Construction, Standard, The total Douglas Fir sawtimber stand in the Western Woods Region is Utility, Economy, 1500f Industrial, and 1200f Industrial grades, estimated at 609 billion board feet. Douglas Fir lumber is used for all giving the user a broad selection from which to choose. purposes to which lumber is normally put - for residential building, light Factory lumber is graded according to the rules for all species, and and heavy construction, woodwork, boxes and crates, industrial usage, separated into Factory Select, No. 1 Shop, No. 2 Shop and No. 3 poles, ties and in the manufacture of specialty products. It is one of the Shop in 5/4 and thicker and into Inch Factory Select and No. 1 and volume woods of the Western Woods Region. No. 2 Shop in 4/4. Distribution Botanical Classification In the Western Douglas Fir is manufactured by a large number of Western Woods Douglas Fir was discovered and classified by botanist David Douglas in Woods Region, Region sawmills and is widely distributed throughout the United 1826. Botanically, it is not a true fir but a species distinct in itself known Douglas Fir trees States and foreign countries. Obtainable in straight car lots, it can as Pseudotsuga taxifolia. -

Current U.S. Forest Data and Maps

CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA AND MAPS Forest age FIA MapMaker CURRENT U.S. Forest ownership TPO Data FOREST DATA Timber harvest AND MAPS Urban influence Forest covertypes Top 10 species Return to FIA Home Return to FIA Home NEXT Productive unreserved forest area CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA (timberland) in the U.S. by region and AND MAPS stand age class, 2002 Return 120 Forests in the 100 South, where timber production West is highest, have 80 s the lowest average age. 60 Northern forests, predominantly Million acreMillion South hardwoods, are 40 of slightly older in average age and 20 Western forests have the largest North concentration of 0 older stands. 1-19 20-39 40-59 60-79 80-99 100- 120- 140- 160- 200- 240- 280- 320- 400+ 119 139 159 199 240 279 319 399 Stand-age Class (years) Return to FIA Home Source: National Report on Forest Resources NEXT CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA Forest ownership AND MAPS Return Eastern forests are predominantly private and western forests are predominantly public. Industrial forests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. Timber harvest by county FOREST DATA AND MAPS Return Timber harvests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. The South is the largest timber producing region in the country accounting for nearly 62% of all U.S. timber harvest. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. -

Folivory of Vine Maple in an Old-Growth Douglas-Fir-Western Hemlock Forest

3589 David M. Braun, Bi Runcheng, David C. Shaw, and Mark VanScoy, University of Washington, Wind River Canopy Crane Research Facility, 1262 Hemlock Rd., Carson, Washington 98610 Folivory of Vine Maple in an Old-growth Douglas-fir-Western Hemlock Forest Abstract Folivory of vine maple was documented in an old-growth Douglas-fir-western hemlock forest in southwest Washington. Leaf consumption by lepidopteran larvae was estimated with a sample of 450 tagged leaves visited weekly from 7 May to 11 October, the period from bud break to leaf drop. Lepidopteran taxa were identified by handpicking larvae from additional shrubs and rearing to adult. Weekly folivory peaked in May at 1.2%, after which it was 0.2% to 0.7% through mid October. Cumulative seasonal herbivory was 9.9% of leaf area. The lepidopteran folivore guild consisted of at least 22 taxa. Nearly all individuals were represented by eight taxa in the Geometridae, Tortricidae, and Gelechiidae. Few herbivores from other insect orders were ob- served, suggesting that the folivore guild of vine maple is dominated by these polyphagous lepidopterans. Vine maple folivory was a significant component of stand folivory, comparable to — 66% of the folivory of the three main overstory conifers. Because vine maple is a regionally widespread, often dominant understory shrub, it may be a significant influence on forest lepidopteran communities and leaf-based food webs. Introduction tract to defoliator outbreaks, less is known about endemic populations of defoliators and low-level Herbivory in forested ecosystems consists of the folivory. consumption of foliage, phloem, sap, and live woody tissue by animals. -

4-H Wood Science Leader Guide Glossary of Woodworking Terms

4-H Wood Science Leader Guide Glossary of Woodworking Terms A. General Terms B. Terms Used in the Lumber Industry d—the abbreviation for “penny” in designating nail boards—Lumber less than 2 inches in nominal size; for example, 8d nails are 8 penny nails, 2½” long. thickness and 1 inch and wider in width. fiber—A general term used for any long, narrow cell of board foot—A measurement of wood. A piece of wood wood or bark, other than vessels. that is 1 foot long by 1 foot wide by 1 inch thick. It can also be other sizes that have the same total amount grain direction—The direction of the annual rings of wood. For example, a piece of wood 2 feet long, showing on the face and sides of a piece of lumber. 6 inches wide, and 1 inch thick; or a piece 1 foot long, hardwood—Wood from a broad leaved tree and 6 inches wide, and 2 inches thick would also be 1 board characterized by the presence of vessels. (Examples: foot. To get the number of board feet in a piece of oak, maple, ash, and birch.) lumber, measure your lumber and multiply Length (in feet) x Width (in feet) x Thickness (in inches). The heartwood—The older, harder, nonliving portion of formula is written: wood. It is usually darker, less permeable, and more durable than sapwood. T” x W’ x L’ T” x W’ x L’ = Board feet or = Board feet 12 kiln dried—Wood seasoned in a humidity and temperature controlled oven to minimize shrinkage T” x W’ x L’ or = Board feet and warping. -

Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite After Infection with the Hymenoscyphus Fraxineus and Phytophthora Species

Article Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite after Infection with the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and Phytophthora Species Nenad Keˇca 1,*, Milosz Tkaczyk 2, Anna Z˙ ółciak 2, Marcin Stocki 3, Hazem M. Kalaji 4 ID , Justyna A. Nowakowska 5 and Tomasz Oszako 2 1 Faculty of Forestry, University of Belgrade, Kneza Višeslava 1, 11030 Belgrade, Serbia 2 Forest Research Institute, Department of Forest Protection, S˛ekocinStary, ul. Braci Le´snej 3, 05-090 Raszyn, Poland; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (A.Z.);˙ [email protected] (T.O.) 3 Faculty of Forestry, Białystok University of Technology, ul. Piłsudskiego 1A, 17-200 Hajnówka, Poland; [email protected] 4 Institute of Technology and Life Sciences (ITP), Falenty, Al. Hrabska 3, 05-090 Raszyn, Poland; [email protected] 5 Faculty of Biology and Environmental Sciences, Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw, Wóycickiego 1/3 Street, 01-938 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +381-63-580-499 Received: 6 June 2018; Accepted: 10 July 2018; Published: 24 July 2018 Abstract: The European Fraxinus species are threatened by the alien invasive pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, which was introduced into Poland in the 1990s and has spread throughout the European continent, causing a large-scale decline of ash. There are no effective treatments to protect ash trees against ash dieback, which is caused by this pathogen, showing high variations in susceptibility at the individual level. Earlier studies have shown that the application of phosphites could improve the health of treated seedlings after artificial inoculation with H. -

Aircraft Wood Information

TL 1.14 Issue 2 1 Jan 2008 AIRCRAFT WOOD INFORMATION Wood is used throughout the world for a wide variety of purposes. It is stronger for its weight than any other material excepting certain alloy steels. Timber is readily worked by hand, using simple tools and is, therefore, far cheaper to use than metal. To appreciate the use of timber in aircraft construction, it is necessary to learn something about the growth and structure of wood. There are two types" of tree—the conifer or evergreen, and the deciduous. A coniferous tree is distinguished by its needle-like leaves. Its seeds are formed in the familiar cone-shaped pod. From a conifer, 'softwood' is obtained. A deciduous tree has broad, flat leaves which it sheds in the autumn. Its seeds are enclosed in ordinary cases as for example, the oak, birch and walnut. Timber from deciduous trees is said to be 'hardwood'. It can be seen, therefore, that the term 'softwood' and 'hardwood' apply to the family or type of tree and do not necessarily indicate the density of the wood. That is why balsa, the lightest and most fragile of woods, is classed as a hardwood. Both hardwood and softwood trees are said to be 'exogenous'. An exogenous tree is one whose growth progresses outwards from the core or heart by the development of additional 'rings' or layers of wood. Certain trees are exceptions to this rule, such as bamboo and palm. This wood is unsuitable for aircraft construction. Exogenous trees grow for only part of the year. -

Hardwood Trees

Tree Identification Guide for Common Native Trees of Nova Scotia Before you Start! • To navigate through this presentation you must use the buttons at the bottom of your screen or select from the underlined choices. • The following presentation includes most of Nova Scotia’s commercial tree species. There are far too many other non-commercial species to cover in this presentation. Please refer to the books listed on the following page for more information. References • Trees of Nova Scotia – Gary Saunders • Native Trees of Canada –R.C. Rosie • Silvics of Forest Trees of the United States – US Department of Agriculture Main Menu Softwood Softwood Key Hardwood Hardwood Key Glossary Glossary of Terms Main Menu Alternate leaf arrangement - one of two kinds of arrangements of leaves along shoots of hardwoods; in this case the leaves appear at staggered intervals along the shoot. Bark - The outer covering of the trunk and branches of a tree, usually corky, papery or leathery. Bud - rounded or conical structures at tips of (terminal buds), or along (lateral or auxiliary buds) stems or branches, usually covered tightly in protective scales and containing a preformed shoot (with leaves), or a preformed inflorescence (with flowers). May or may not be on a stalk. Clear cut - a silvicultural system that removes an entire stand of trees from an area of one hectare or more, and greater that two tree heights in width, in a single harvesting operation. Compound leaf - a leaf divided into smaller leaflets. Cone - in botany, a reproductive structure bearing seeds (seed cone) or pollen (pollen cone) in conifers. -

INDENTATION HARDNESS of WOOD J. Doyle1 and J. C. F. Walker School of Forestry, University of Canterbury Christchurch 1, New Zealand (Received March 1984)

INDENTATION HARDNESS OF WOOD J. Doyle1 and J. C. F. Walker School of Forestry, University of Canterbury Christchurch 1, New Zealand (Received March 1984) ABSTRACT An historical background to hardness testing of wood is given, and the advantages and disadvantages of the methods used are reviewed. A new method, using a wedge indenter, is suggested and a rationale presented that includes discussion of the deformation patterns beneath indenting tools. Keywords: Ball, Brinell, cone, cylinder, hardness, Janka, Meyer, Monnin, wedge. INTRODUCTION Hardness testing of wood has made little progress since Janka (1 906). Although there have been many studies leading to a variety of tests, there are shortcomings with all of them. Furthermore, the various hardness values are not easily com- parable one to another and do not allow comparison with those for other materials, where testing procedures have a more rational basis. The wedge test that we advocate does allow for comparison with other materials while also taking account of wood anisotropy. Hardness implies the ability of a body to resist deformation. In a typical test a hard tool of known geometry is forced into the body, and the hardness is defined as the ratio of the applied force to the size of the indentation. This size depends on whether it is determined under load or on unloading. With elastic materials it is determined under load as there will be little or no permanent deformation, whereas with plastic materials the size of the permanent indentation is measured (Tabor 195 1). With wood there are difficulties in measuring the impression, especially for shallow indentations where the imprint is indistinct.