U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Informational Meeting on Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa's Sudano- Sahel: Emerging Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinko/Mbari Drainage Basin Represents a Conservation Hotspot for Eastern Derby Eland in Central Africa

Published in "African Journal of Ecology 56 (2): 194–201, 2018" which should be cited to refer to this work. Chinko/Mbari drainage basin represents a conservation hotspot for Eastern Derby eland in Central Africa Karolına Brandlova1 | Marketa Glonekova1 | Pavla Hejcmanova1 | Pavla Jůnkova Vymyslicka1 | Thierry Aebischer2 | Raffael Hickisch3 | David Mallon4 1Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Praha 6, Abstract Czech Republic One of the largest of antelopes, Derby eland (Taurotragus derbianus), is an important 2Department of Biology, University of ecosystem component of African savannah. While the western subspecies is Critically Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland 3Chinko Project, Operations, Chinko, Endangered, the eastern subspecies is classified as least concern. Our study presents the Bangui, Central African Republic first investigation of population dynamics of the Derby eland in the Chinko/Mbari Drai- 4 Co-Chair, IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist nage Basin, Central African Republic, and assesses the conservation role of this popula- Group and Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, Manchester tion. We analysed data from 63 camera traps installed in 2012. The number of individuals Metropolitan University, Glossop, UK captured within a single camera event ranged from one to 41. Herds were mostly mixed Correspondence by age and sex, mean group size was 5.61, larger during the dry season. Adult (AD) males ı Karol na Brandlova constituted only 20% of solitary individuals. The overall sex ratio (M:F) was 1:1.33, while Email: [email protected] the AD sex ratio shifted to 1:1.52, reflecting selective hunting pressure. Mean density Funding information ranged from 0.04 to 0.16 individuals/km2, giving an estimated population size of 445– Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Grant/Award Number: 20135010, 1,760 individuals. -

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N'djida

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape Northern Cameroon and Southwestern Chad April - May 2015 Paul Elkan, Roger Fotso, Chris Hamley, Soqui Mendiguetti, Paul Bour, Vailia Nguertou Alexandre, Iyah Ndjidda Emmanuel, Mbamba Jean Paul, Emmanuel Vounserbo, Etienne Bemadjim, Hensel Fopa Kueteyem and Kenmoe Georges Aime Wildlife Conservation Society Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) L'Ecole de Faune de Garoua Funded by the Great Elephant Census Paul G. Allen Foundation and WCS SUMMARY The Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape is located in north Cameroon and extends into southwest Chad. It consists of Bouba N’djida, Sena Oura, Benoue and Faro National Parks, in addition to 25 safari hunting zones. Along with Zakouma NP in Chad and Waza NP in the Far North of Cameroon, the landscape represents one of the most important areas for savanna elephant conservation remaining in Central Africa. Aerial wildlife surveys in the landscape were first undertaken in 1977 by Van Lavieren and Esser (1979) focusing only on Bouba N’djida NP. They documented a population of 232 elephants in the park. After a long period with no systematic aerial surveys across the area, Omondi et al (2008) produced a minimum count of 525 elephants for the entire landscape. This included 450 that were counted in Bouba N’djida NP and its adjacent safari hunting zones. The survey also documented a high richness and abundance of other large mammals in the Bouba N’djida NP area, and to the southeast of Faro NP. In the period since 2010, a number of large-scale elephant poaching incidents have taken place in Bouba N’djida NP. -

Beatragus Hunteri) in Arawale National Reserve, Northeastern, Kenya

The population size, abundance and distribution of the Critically Endangered Hirola Antelope (Beatragus hunteri) in Arawale National Reserve, Northeastern, Kenya. Francis Kamau Muthoni Terra Nuova, Transboundary Environmental Project, P.O. Box 74916, Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] 1.0. Abstract. This paper outlines the spatial distribution, population size, habitat preferences and factors causing the decline of Hirola antelope in Arawale National Reserve (ANR) in Garissa and Ijara districts, north eastern Kenya. The reserve covers an area of 540Km2. The objectives of the study were to gather baseline information on hirola distribution, population size habitat preferences and human activities impacting on its existence. A sampling method using line transect count was used to collect data used to estimate the distribution of biological populations (Norton-Griffiths, 1978). Community scouts collected data using Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and recorded on standard datasheets for 12 months. Transect walks were done from 6.00Am to 10.00Am every 5th day of the month. The data was entered into a geo-database and analysed using Arcmap, Ms Excel and Access. The results indicate that the population of hirola in Arawale National Reserve were 69 individuals comprising only 6% of the total population in the natural geographic range of hirola estimated to be 1,167 individuals. It also revealed that hirola prefer open bushes and grasslands. The decline of the Hirola on its natural range is due to a combination of factors, including, habitat loss and degradation, competition with livestock, poaching and drought. Key words: Hirola Antelope Beatragus hunteri, GIS, Endangered Species 2.0. Introduction. The Hirola antelope (Beatragus hunteri) is a “Critically Endangered” species endemic to a small area in Southeast Kenya and Southwest Somalia. -

African Parks 2 African Parks

African Parks 2 African Parks African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation that takes on the total responsibility for the rehabilitation and long-term management of national parks in partnership with governments and local communities. By adopting a business approach to conservation, supported by donor funding, we aim to rehabilitate each park making them ecologically, socially and financially sustainable in the long-term. Founded in 2000, African Parks currently has 15 parks under management in nine countries – Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia. More than 10.5 million hectares are under our protection. We also maintain a strong focus on economic development and poverty alleviation in neighbouring communities, ensuring that they benefit from the park’s existence. Our goal is to manage 20 parks by 2020, and because of the geographic spread and representation of different ecosystems, this will be the largest and the most ecologically diverse portfolio of parks under management by any one organisation across Africa. Black lechwe in Bangweulu Wetlands in Zambia © Lorenz Fischer The Challenge The world’s wild and functioning ecosystems are fundamental to the survival of both people and wildlife. We are in the midst of a global conservation crisis resulting in the catastrophic loss of wildlife and wild places. Protected areas are facing a critical period where the number of well-managed parks is fast declining, and many are simply ‘paper parks’ – they exist on maps but in reality have disappeared. The driving forces of this conservation crisis is the human demand for: 1. -

Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa's Sudano-Sahel

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa’s Sudano-Sahel The interface of conservation, security, and development Mbororo pastoralists illegally grazing cattle in Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Credit: Naftali Honig/African Parks Africa’s Sudano-Sahel is a distinct bioclimatic and ecological zone made up of savanna and savanna-forest transition Program Priorities habitat that covers approximately 7.7 million square kilometers of the continent. Rich in species diversity, the • Increased data gathering and assessment of core Sudano-Sahel region represents one of the last remaining natural resource assets across the Sudano-Sahel region. intact wilderness areas in the world, and is a high priority • Efficient data-sharing, analysis, and dissemination for wildlife conservation. It is home to an array of antelope between relevant stakeholders spanning conservation, species such as giant eland and greater kudu, in addition to security, and development sectors, and in collaboration African wild dog, Kordofan giraffe, African elephant, African with rural agriculturalists and pastoralists. lion, leopard, and giant pangolin. • Enhancement and promotion of multi-level This region is also home to many rural communities who rely governance approaches to resolve conflict and stabilize on the landscape’s natural resources, including pastoralists, transhumance corridors. whose livelihoods and cultural identity are centered around • Continuation and expansion of strategic investments in strategic mobility to access seasonally available grazing the network of priority protected areas and their buffer resources and water. Instability, climate change, and zones across the Sudano-Sahel, in order to improve increasing pressures from unsustainable land use activities security for both wildlife and surrounding communities. -

Evaluating Support for Rangeland‐Restoration Practices by Rural Somalis

Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Evaluating support for rangeland-restoration practices by rural Somalis: an unlikely win-win for local livelihoods and hirola antelope? A. H. Ali1,2,3 ,R.Amin4, J. S. Evans1,5, M. Fischer6, A. T. Ford7, A. Kibara3 & J. R. Goheen1 1 Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA 2 National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya 3 Hirola Conservation Programme, Garissa, Kenya 4 Conservation Programmes, Zoological Society of London, London, UK 5 The Nature Conservancy, Fort Collins, CO, USA 6 Center for Conservation in the Horn of Africa, St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO, USA 7 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada Keywords Abstract Beatragus hunteri; elephant; endangered species; habitat degradation; rangeland; In developing countries, governments often lack the authority and resources to restoration; tree encroachment; antelope. implement conservation outside of protected areas. In such situations, the integra- tion of conservation with local livelihoods is crucial to species recovery and rein- Correspondence troduction efforts. The hirola Beatragus hunteri is the world’s most endangered Abdullahi H. Ali, Department of Zoology and antelope, with a population of <500 individuals that is restricted to <5% of its his- Physiology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, torical geographic range on the Kenya–Somali border. Long-term hirola declines WY, USA. have been attributed to a combination of disease and rangeland degradation. Tree Email: [email protected] encroachment—driven by some combination of extirpation of elephants, overgraz- ing by livestock, and perhaps fire suppression—is at least partly responsible for Editor: Darren Evans habitat loss and the decline of contemporary populations. -

The Hirola Conservation Programme (Hcp) Progress Report, October, 2015

THE HIROLA CONSERVATION PROGRAMME (HCP) PROGRESS REPORT, OCTOBER, 2015 The Hirola Conservation Programme (HCP) is a non-governmental organization based in Garissa County in north-eastern Kenya. The HCP is primarily dedicated to promoting conservation of the endangered hirola antelope (Beatragus hunteri) in the region (Figure 1). Towards this, HCP commits itself to improving hirola’s habitat in partnership with the local pastoralist groups. The main goal of HCP is to establish and sustain a conservation programme that will make a lasting contribution to the future of hirola antelope and also the livelihoods of the local communities living within hirola’s geographical range. One of the key concerns for conservation of hirola antelope is Figure 1: Herd of hirola within Ishaqbini Conservancy. that, their population have declined from approximately 15,000 individuals in 1970 to between 300 and 500 individuals currently. That is why our programme focuses on in situ conservation within the species historic geographical range to ensure that we achieve our objective in partnership with local communities. Specifically, for long-term monitoring of this critically-endangered species, the programme intends to protect and increase the numbers and distribution of hirola through local participatory conservation, education, and international support in north-eastern Kenya. Our core functions include: A) Conservation Our conservation efforts are threefold 1) The protection and restoration of habitat for the endangered hirola antelope 2) Anti-poaching programme for hirola, elephants and other wildlife and, 3) Capacity building and technical advice to both local government officials and local groups. B) Research Our research programme is a locally supported conservation research effort that aims at understanding the underlying factors influencing hirola declines and to explore the best management interventions to improve their population. -

Chapter 2 Transboundary Environmental Issues

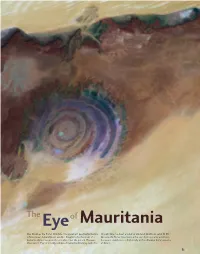

The Eyeof Mauritania Also known as the Richat Structure, this prominent geographic feature through time, has been eroded by wind and windblown sand. At 50 in Mauritania’s Sahara Desert was fi rst thought to be the result of a km wide, the Richat Structure can be seen from space by astronauts meteorite impact because of its circular, crater-like pattern. However, because it stands out so dramatically in the otherwise barren expanse Mauritania’s “Eye” is actually a dome of layered sedimentary rock that, of desert. Source: NASA Source: 37 ey/Flickr.com A man singing by himself on the Jemaa Fna Square, Morocco Charles Roff 38 Chapter2 Transboundary Environmental Issues " " Algiers Tunis TUNISIA " Rabat " Tripoli MOROCCO " Cairo ALGERIA LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA EGYPT WESTERN SAHARA MAURITANIA " Nouakchott CAPE VERDE MALI NIGER CHAD Khartoum " ERITREA " " Dakar Asmara Praia " SENEGAL Banjul Niamey SUDAN GAMBIA " " Bamako " Ouagadougou " Ndjamena " " Bissau DJIBOUTI BURKINA FASO " Djibouti GUINEA Conakry NIGERIA GUINEA-BISSAU " ETHIOPIA " " Freetown " Abuja Addis Ababa COTE D’IVORE BENIN LIBERIA TOGO GHANA " " CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SIERRA LEONE " Yamoussoukro " IA Accra Porto Novo L Monrovia " Lome A CAMEROON OM Bangui" S Malabo Yaounde " " EQUATORIAL GUINEA Mogadishu " UGANDA SAO TOME Kampala AND PRINCIPE " " Libreville " KENYA Sao Tome Nairobi GABON " Kigali CONGO " DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC RWANDA OF THE CONGO " Bujumbura Brazzaville BURUNDI "" Kinshasa UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA " Dodoma SEYCHELLES " Luanda Moroni " COMOROS Across Country Borders ANGOLA Lilongwe " MALAWI ZAMBIA Politically, the African continent is divided into 53 countries " Lusaka UE BIQ and one “non-self-governing territory.” Ecologically, Harare M " A Z O M Antananarivo" Port Louis Africa is home to eight major biomes— large and distinct ZIMBABWE " biotic communities— whose characteristic assemblages MAURITIUS Windhoek " BOTSWANA MADAGASCAR of fl ora and fauna are in many cases transboundary in NAMIBIA Gaborone " Maputo nature, in that they cross political borders. -

GNUSLETTER Volume 37 Number 1

GNUSLETTER Volume 37 Number 1 ANTELOPE SPECIALIST GROUP July 2020 ISSN 2304-0718 IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group GNUSLETTER is the biannual newsletter of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group (ASG). First published in 1982 by first ASG Chair Richard D. Estes, the intent of GNUSLETTER, then and today, is the dissemination of reports and information regarding antelopes and their conservation. ASG Members are an important network of individuals and experts working across disciplines throughout Africa and Asia. Contributions (original articles, field notes, other material relevant to antelope biology, ecology, and conservation) are welcomed and should be sent to the editor. Today GNUSLETTER is published in English in electronic form and distributed widely to members and non-members, and to the IUCN SSC global conservation network. To be added to the distribution list please contact [email protected]. GNUSLETTER Review Board Editor, Steve Shurter, [email protected] Co-Chair, David Mallon Co-Chair, Philippe Chardonnet ASG Program Office, Tania Gilbert, Phil Riordan GNUSLETTER Editorial Assistant, Stephanie Rutan GNUSLETTER is published and supported by White Oak Conservation The Antelope Specialist Group Program Office is hosted and supported by Marwell Zoo http://www.whiteoakwildlife.org/ https://www.marwell.org.uk The designation of geographical entities in this report does not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of IUCN, the Species Survival Commission, or the Antelope Specialist Group concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or concerning the delimitation of any frontiers or boundaries. Views expressed in Gnusletter are those of the individual authors, Cover photo: Peninsular pronghorn male, El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve (© J. -

Private Governance of Protected Areas in Africa: Case Studies, Lessons Learnt and Conditions of Success

Program on African Protected Areas & Conservation (PAPACO) PAPACO study 19 Private governance of protected areas in Africa: case studies, lessons learnt and conditions of success @B. Chataigner Sue Stolton and Nigel Dudley Equilibrium Research & IIED Equilibrium Research offers practical solutions to conservation challenges, from concept, to implementation, to evaluation of impact. With partners ranging from local communities to UN agencies across the world, we explore and develop approaches to natural resource management that balance the needs of nature and people. We see biodiversity conservation as an ethical necessity, which can also support human wellbeing. We run our own portfolio of projects and offer personalised consultancy. Prepared for: IIED under contract to IUCN EARO Reproduction: This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from Equilibrium Research. Citation: Stolton, S and N Dudley (2015). Private governance of protected areas in Africa: Cases studies, lessons learnt and conditions of success. Bristol, UK, Equilibrium Research and London, UK, IIED Cover: Private conservancies in Namibia and Kenya © Equilibrium Research Contact: Equilibrium Research, 47 The Quays Cumberland Road, Spike Island Bristol, BS1 6UQ, UK Telephone: +44 [0]117-925-5393 www.equilibriumconsultants.com Page | 2 Contents 1. Executive summary -

Gammaherpesvirus in Semi-Domesticated Reindeer (Rangifer Tarandus Tarandus) in Finnmark County, Norway

FACULTY OF BIOSCIENCES, FISHERIES AND ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF ARCTIC AND MARINE BIOLOGY Gammaherpesvirus in semi-domesticated reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) in Finnmark County, Norway Hanne Marie Ihlebæk BIO-3900 Master`s thesis in Arctic natural resource management and agriculture May 2010 2 Gammaherpesvirus in semi-domesticated reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) in Finnmark County, Norway Hanne Marie Ihlebæk May 2010 In collaboration with The Norwegian School of Veterinary Science Section of Arctic Veterinary Medicine 3 4 Acknowledgments This thesis was part of the research project Reinhelse 2008–2010, under direction of The Norwegian School of Veterinary Science, Section of Arctic Veterinary Medicine (SAV), Tromsø. The project was partly funded by the Norwegian Reindeer Development Fund (RUF). Several people have contributed with help on this thesis. First of all I owe a very special thank to my main supervisor Morten Tryland for giving me the opportunity to work with this project and for all guidance and trust throughout this period. I also wish to thank my supervisor Willy Hemmingsen for all helpful advises and comments on the writing process of my thesis. My special acknowledgement also goes to the laboratory personal and especially Eva Marie Breines for invaluable guidance in the laboratory, to Carlos das Neves for excellent help with the PCR results and to Eystein Skjerve for help with the statistical model, Kjetil Åsbakk for guiding me into JMP and Trond Elde for genuine help with an easy going database. Thanks to Maret Haetta, Carlos and Alina Evans for enjoyable company at fieldwork. At last I will thank my parents for all support and love. -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian