Eb/N0 Explained

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All You Need to Know About SINAD Measurements Using the 2023

applicationapplication notenote All you need to know about SINAD and its measurement using 2023 signal generators The 2023A, 2023B and 2025 can be supplied with an optional SINAD measuring capability. This article explains what SINAD measurements are, when they are used and how the SINAD option on 2023A, 2023B and 2025 performs this important task. www.ifrsys.com SINAD and its measurements using the 2023 What is SINAD? C-MESSAGE filter used in North America SINAD is a parameter which provides a quantitative Psophometric filter specified in ITU-T Recommendation measurement of the quality of an audio signal from a O.41, more commonly known from its original description as a communication device. For the purpose of this article the CCITT filter (also often referred to as a P53 filter) device is a radio receiver. The definition of SINAD is very simple A third type of filter is also sometimes used which is - its the ratio of the total signal power level (wanted Signal + unweighted (i.e. flat) over a broader bandwidth. Noise + Distortion or SND) to unwanted signal power (Noise + The telephony filter responses are tabulated in Figure 2. The Distortion or ND). It follows that the higher the figure the better differences in frequency response result in different SINAD the quality of the audio signal. The ratio is expressed as a values for the same signal. The C-MES signal uses a reference logarithmic value (in dB) from the formulae 10Log (SND/ND). frequency of 1 kHz while the CCITT filter uses a reference of Remember that this a power ratio, not a voltage ratio, so a 800 Hz, which results in the filter having "gain" at 1 kHz. -

Noise Tutorial Part IV ~ Noise Factor

Noise Tutorial Part IV ~ Noise Factor Whitham D. Reeve Anchorage, Alaska USA See last page for document information Noise Tutorial IV ~ Noise Factor Abstract: With the exception of some solar radio bursts, the extraterrestrial emissions received on Earth’s surface are very weak. Noise places a limit on the minimum detection capabilities of a radio telescope and may mask or corrupt these weak emissions. An understanding of noise and its measurement will help observers minimize its effects. This paper is a tutorial and includes six parts. Table of Contents Page Part I ~ Noise Concepts 1-1 Introduction 1-2 Basic noise sources 1-3 Noise amplitude 1-4 References Part II ~ Additional Noise Concepts 2-1 Noise spectrum 2-2 Noise bandwidth 2-3 Noise temperature 2-4 Noise power 2-5 Combinations of noisy resistors 2-6 References Part III ~ Attenuator and Amplifier Noise 3-1 Attenuation effects on noise temperature 3-2 Amplifier noise 3-3 Cascaded amplifiers 3-4 References Part IV ~ Noise Factor 4-1 Noise factor and noise figure 4-1 4-2 Noise factor of cascaded devices 4-7 4-3 References 4-11 Part V ~ Noise Measurements Concepts 5-1 General considerations for noise factor measurements 5-2 Noise factor measurements with the Y-factor method 5-3 References Part VI ~ Noise Measurements with a Spectrum Analyzer 6-1 Noise factor measurements with a spectrum analyzer 6-2 References See last page for document information Noise Tutorial IV ~ Noise Factor Part IV ~ Noise Factor 4-1. Noise factor and noise figure Noise factor and noise figure indicates the noisiness of a radio frequency device by comparing it to a reference noise source. -

Next Topic: NOISE

ECE145A/ECE218A Performance Limitations of Amplifiers 1. Distortion in Nonlinear Systems The upper limit of useful operation is limited by distortion. All analog systems and components of systems (amplifiers and mixers for example) become nonlinear when driven at large signal levels. The nonlinearity distorts the desired signal. This distortion exhibits itself in several ways: 1. Gain compression or expansion (sometimes called AM – AM distortion) 2. Phase distortion (sometimes called AM – PM distortion) 3. Unwanted frequencies (spurious outputs or spurs) in the output spectrum. For a single input, this appears at harmonic frequencies, creating harmonic distortion or HD. With multiple input signals, in-band distortion is created, called intermodulation distortion or IMD. When these spurs interfere with the desired signal, the S/N ratio or SINAD (Signal to noise plus distortion ratio) is degraded. Gain Compression. The nonlinear transfer characteristic of the component shows up in the grossest sense when the gain is no longer constant with input power. That is, if Pout is no longer linearly related to Pin, then the device is clearly nonlinear and distortion can be expected. Pout Pin P1dB, the input power required to compress the gain by 1 dB, is often used as a simple to measure index of gain compression. An amplifier with 1 dB of gain compression will generate severe distortion. Distortion generation in amplifiers can be understood by modeling the amplifier’s transfer characteristic with a simple power series function: 3 VaVaVout=−13 in in Of course, in a real amplifier, there may be terms of all orders present, but this simple cubic nonlinearity is easy to visualize. -

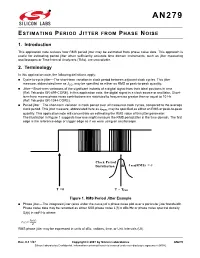

AN279: Estimating Period Jitter from Phase Noise

AN279 ESTIMATING PERIOD JITTER FROM PHASE NOISE 1. Introduction This application note reviews how RMS period jitter may be estimated from phase noise data. This approach is useful for estimating period jitter when sufficiently accurate time domain instruments, such as jitter measuring oscilloscopes or Time Interval Analyzers (TIAs), are unavailable. 2. Terminology In this application note, the following definitions apply: Cycle-to-cycle jitter—The short-term variation in clock period between adjacent clock cycles. This jitter measure, abbreviated here as JCC, may be specified as either an RMS or peak-to-peak quantity. Jitter—Short-term variations of the significant instants of a digital signal from their ideal positions in time (Ref: Telcordia GR-499-CORE). In this application note, the digital signal is a clock source or oscillator. Short- term here means phase noise contributions are restricted to frequencies greater than or equal to 10 Hz (Ref: Telcordia GR-1244-CORE). Period jitter—The short-term variation in clock period over all measured clock cycles, compared to the average clock period. This jitter measure, abbreviated here as JPER, may be specified as either an RMS or peak-to-peak quantity. This application note will concentrate on estimating the RMS value of this jitter parameter. The illustration in Figure 1 suggests how one might measure the RMS period jitter in the time domain. The first edge is the reference edge or trigger edge as if we were using an oscilloscope. Clock Period Distribution J PER(RMS) = T = 0 T = TPER Figure 1. RMS Period Jitter Example Phase jitter—The integrated jitter (area under the curve) of a phase noise plot over a particular jitter bandwidth. -

Receiver Sensitivity and Equivalent Noise Bandwidth Receiver Sensitivity and Equivalent Noise Bandwidth

11/08/2016 Receiver Sensitivity and Equivalent Noise Bandwidth Receiver Sensitivity and Equivalent Noise Bandwidth Parent Category: 2014 HFE By Dennis Layne Introduction Receivers often contain narrow bandpass hardware filters as well as narrow lowpass filters implemented in digital signal processing (DSP). The equivalent noise bandwidth (ENBW) is a way to understand the noise floor that is present in these filters. To predict the sensitivity of a receiver design it is critical to understand noise including ENBW. This paper will cover each of the building block characteristics used to calculate receiver sensitivity and then put them together to make the calculation. Receiver Sensitivity Receiver sensitivity is a measure of the ability of a receiver to demodulate and get information from a weak signal. We quantify sensitivity as the lowest signal power level from which we can get useful information. In an Analog FM system the standard figure of merit for usable information is SINAD, a ratio of demodulated audio signal to noise. In digital systems receive signal quality is measured by calculating the ratio of bits received that are wrong to the total number of bits received. This is called Bit Error Rate (BER). Most Land Mobile radio systems use one of these figures of merit to quantify sensitivity. To measure sensitivity, we apply a desired signal and reduce the signal power until the quality threshold is met. SINAD SINAD is a term used for the Signal to Noise and Distortion ratio and is a type of audio signal to noise ratio. In an analog FM system, demodulated audio signal to noise ratio is an indication of RF signal quality. -

Signal-To-Noise Ratio and Dynamic Range Definitions

Signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range definitions The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Dynamic Range (DR) are two common parameters used to specify the electrical performance of a spectrometer. This technical note will describe how they are defined and how to measure and calculate them. Figure 1: Definitions of SNR and SR. The signal out of the spectrometer is a digital signal between 0 and 2N-1, where N is the number of bits in the Analogue-to-Digital (A/D) converter on the electronics. Typical numbers for N range from 10 to 16 leading to maximum signal level between 1,023 and 65,535 counts. The Noise is the stochastic variation of the signal around a mean value. In Figure 1 we have shown a spectrum with a single peak in wavelength and time. As indicated on the figure the peak signal level will fluctuate a small amount around the mean value due to the noise of the electronics. Noise is measured by the Root-Mean-Squared (RMS) value of the fluctuations over time. The SNR is defined as the average over time of the peak signal divided by the RMS noise of the peak signal over the same time. In order to get an accurate result for the SNR it is generally required to measure over 25 -50 time samples of the spectrum. It is very important that your input to the spectrometer is constant during SNR measurements. Otherwise, you will be measuring other things like drift of you lamp power or time dependent signal levels from your sample. -

Image Denoising by Autoencoder: Learning Core Representations

Image Denoising by AutoEncoder: Learning Core Representations Zhenyu Zhao College of Engineering and Computer Science, The Australian National University, Australia, [email protected] Abstract. In this paper, we implement an image denoising method which can be generally used in all kinds of noisy images. We achieve denoising process by adding Gaussian noise to raw images and then feed them into AutoEncoder to learn its core representations(raw images itself or high-level representations).We use pre- trained classifier to test the quality of the representations with the classification accuracy. Our result shows that in task-specific classification neuron networks, the performance of the network with noisy input images is far below the preprocessing images that using denoising AutoEncoder. In the meanwhile, our experiments also show that the preprocessed images can achieve compatible result with the noiseless input images. Keywords: Image Denoising, Image Representations, Neuron Networks, Deep Learning, AutoEncoder. 1 Introduction 1.1 Image Denoising Image is the object that stores and reflects visual perception. Images are also important information carriers today. Acquisition channel and artificial editing are the two main ways that corrupt observed images. The goal of image restoration techniques [1] is to restore the original image from a noisy observation of it. Image denoising is common image restoration problems that are useful by to many industrial and scientific applications. Image denoising prob- lems arise when an image is corrupted by additive white Gaussian noise which is common result of many acquisition channels. The white Gaussian noise can be harmful to many image applications. Hence, it is of great importance to remove Gaussian noise from images. -

AN10062 Phase Noise Measurement Guide for Oscillators

Phase Noise Measurement Guide for Oscillators Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2 What is phase noise ................................................................................................................................. 2 3 Methods of phase noise measurement ................................................................................................... 3 4 Connecting the signal to a phase noise analyzer ..................................................................................... 4 4.1 Signal level and thermal noise ......................................................................................................... 4 4.2 Active amplifiers and probes ........................................................................................................... 4 4.3 Oscillator output signal types .......................................................................................................... 5 4.3.1 Single ended LVCMOS ........................................................................................................... 5 4.3.2 Single ended Clipped Sine ..................................................................................................... 5 4.3.3 Differential outputs ............................................................................................................... 6 5 Setting up a phase noise analyzer ........................................................................................................... -

Active Noise Control Over Space: a Subspace Method for Performance Analysis

applied sciences Article Active Noise Control over Space: A Subspace Method for Performance Analysis Jihui Zhang 1,* , Thushara D. Abhayapala 1 , Wen Zhang 1,2 and Prasanga N. Samarasinghe 1 1 Audio & Acoustic Signal Processing Group, College of Engineering and Computer Science, Australian National University, Canberra 2601, Australia; [email protected] (T.D.A.); [email protected] (W.Z.); [email protected] (P.N.S.) 2 Center of Intelligent Acoustics and Immersive Communications, School of Marine Science and Technology, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi0an 710072, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 February 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2019; Published: 25 March 2019 Abstract: In this paper, we investigate the maximum active noise control performance over a three-dimensional (3-D) spatial space, for a given set of secondary sources in a particular environment. We first formulate the spatial active noise control (ANC) problem in a 3-D room. Then we discuss a wave-domain least squares method by matching the secondary noise field to the primary noise field in the wave domain. Furthermore, we extract the subspace from wave-domain coefficients of the secondary paths and propose a subspace method by matching the secondary noise field to the projection of primary noise field in the subspace. Simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithms by comparison between the wave-domain least squares method and the subspace method, more specifically the energy of the loudspeaker driving signals, noise reduction inside the region, and residual noise field outside the region. We also investigate the ANC performance under different loudspeaker configurations and noise source positions. -

Topic 5: Noise in Images

NOISE IN IMAGES Session: 2007-2008 -1 Topic 5: Noise in Images 5.1 Introduction One of the most important consideration in digital processing of images is noise, in fact it is usually the factor that determines the success or failure of any of the enhancement or recon- struction scheme, most of which fail in the present of significant noise. In all processing systems we must consider how much of the detected signal can be regarded as true and how much is associated with random background events resulting from either the detection or transmission process. These random events are classified under the general topic of noise. This noise can result from a vast variety of sources, including the discrete nature of radiation, variation in detector sensitivity, photo-graphic grain effects, data transmission errors, properties of imaging systems such as air turbulence or water droplets and image quantsiation errors. In each case the properties of the noise are different, as are the image processing opera- tions that can be applied to reduce their effects. 5.2 Fixed Pattern Noise As image sensor consists of many detectors, the most obvious example being a CCD array which is a two-dimensional array of detectors, one per pixel of the detected image. If indi- vidual detector do not have identical response, then this fixed pattern detector response will be combined with the detected image. If this fixed pattern is purely additive, then the detected image is just, f (i; j) = s(i; j) + b(i; j) where s(i; j) is the true image and b(i; j) the fixed pattern noise. -

Understanding Noise Figure

Understanding Noise Figure Iulian Rosu, YO3DAC / VA3IUL, http://www.qsl.net/va3iul One of the most frequently discussed forms of noise is known as Thermal Noise. Thermal noise is a random fluctuation in voltage caused by the random motion of charge carriers in any conducting medium at a temperature above absolute zero (K=273 + °Celsius). This cannot exist at absolute zero because charge carriers cannot move at absolute zero. As the name implies, the amount of the thermal noise is to imagine a simple resistor at a temperature above absolute zero. If we use a very sensitive oscilloscope probe across the resistor, we can see a very small AC noise being generated by the resistor. • The RMS voltage is proportional to the temperature of the resistor and how resistive it is. Larger resistances and higher temperatures generate more noise. The formula to find the RMS thermal noise voltage Vn of a resistor in a specified bandwidth is given by Nyquist equation: Vn = 4kTRB where: k = Boltzmann constant (1.38 x 10-23 Joules/Kelvin) T = Temperature in Kelvin (K= 273+°Celsius) (Kelvin is not referred to or typeset as a degree) R = Resistance in Ohms B = Bandwidth in Hz in which the noise is observed (RMS voltage measured across the resistor is also function of the bandwidth in which the measurement is made). As an example, a 100 kΩ resistor in 1MHz bandwidth will add noise to the circuit as follows: -23 3 6 ½ Vn = (4*1.38*10 *300*100*10 *1*10 ) = 40.7 μV RMS • Low impedances are desirable in low noise circuits. -

Noise, Distortion and Mixing Lab

EECS 142 Noise, Distortion and Mixing Lab A. M. Niknejad Berkeley Wireless Research Center University of California, Berkeley 2108 Allston Way, Suite 200 Berkeley, CA 94704-1302 November 25, 2008 1 1 Prelab In this laboratory you will measure and characterize the non-linear and noise properties of your amplifier. If you were not able to get your amplifier to work correctly, a few working amplifiers are available. Even though your amplifier likely incorporates many inductors and capacitors, elements with memory, a simple memoryless power series analysis is still appli- cable if special care is taken in your calculations. In particular, the memoryless portion and filtering effects of the inductors and capacitors can often be separated and analyzed sepa- rately. For instance, if two tones are applied in the band of interest, then the harmonics are heavily attenuated by the LC tuning/matching networks, but the intermodulation products that fall in-band remain unfiltered. Likewise, if your amplifier uses feedback, be sure to calculate the loop gain at the frequency product of interest when analyzing the effect of the feedback on the amplifier performance. 1. Begin by calculating a power series representation for the in-band performance of the amplifier design. Assume that the amplifier is operating in resonance so that many LC elements resonate out and only the resistive parasitic effects remain. 2. From the power series, predict the harmonic powers (2nd, 3rd) and intermodulation powers for a 600 MHz input(s) with -30 dBm input power. If your amplifier center frequency is different, use the actual center frequency for the measurements.