Scholastic Art & Writing Awards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Abstract Birds, Children, and Lonely Men in Cars and The

ABSTRACT BIRDS, CHILDREN, AND LONELY MEN IN CARS AND THE SOUND OF WRONG by Justin Edwards My thesis is a collection of short stories. Much of the work is thematically centered around loneliness, mostly within the domestic household, and the lengths that people go to get out from under it. The stories are meant to be comic yet dark. Both the humor and the tension comes from the way in which the characters overreact to the point where either their reality changes a bit to allow it for it, or they are simply fooling themselves. Overall, I am trying to find the best possible way to describe something without actually describing it. I am working towards the peripheral, because I feel that readers believe it is better than what is out in front. BIRDS, CHILDREN, AND LONELY MEN IN CARS AND THE SOUND OF WRONG A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Justin Edwards Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor:__________________________ Margaret Luongo Reader: ___________________________ Brian Roley Reader:____________________________ Susan Kay Sloan Table of Contents Bailing ........................................................................1 Dating ........................................................................14 Rake Me Up Before You Go ....................................17 The Way to My Heart ................................................26 Leaving Together ................................................27 The End -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

SFJAZZ Announces 2019-2020 Season Programming September 5, 2019 – May 31, 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SFJAZZ Announces 2019-2020 Season Programming September 5, 2019 – May 31, 2020 Tickets on Sale to SFJAZZ Members, Friday, June 28 at 11:00amPST Tickets on Sale to Public, Thursday, July 12 at 11:00amPST SFJAZZ.ORG (SAN FRANCISCO, CA, June 6, 2019) -- SFJAZZ announces artist programming for the 2019-20 season running September 5, 2019 to May 31, 2020 presenting concerts at the SFJAZZ Center’s Robert N. Miner Auditorium and Joe Henderson Lab, Herbst Theatre, Grace Cathedral, and Paramount Theatre in Oakland. Tickets on sale to SFJAZZ Members, Friday, June 28 at 11:00amPST and on sale to public on Thursday, July 12 at 11:00amPST. For more information, visit sfjazz.org. “This is our 8th Season in the Center: we opened in January of 2013. And it is SFJAZZ’s 37th year: we debuted in 1983 as Jazz in the City,” says SFJAZZ Founder and Artistic Director Randall Kline. “At the time of our founding, neither I, nor anyone who was a part of it, could have imagined that here at the corner of Franklin Street and Fell Street, in one of the world’s greatest cities, a dedicated community center built expressly for the appreciation and development of jazz would be thriving. The key elements of this vitality are the intersection of our dedicated audiences, our superb artists, and the Center itself—we work together to create this community.” The SFJAZZ Resident Artistic Director program was established to give today’s most innovative and influential artists the chance to curate exclusive programming at the SFJAZZ Center often featuring unprecedented collaborations and world premiere projects between world-renowned artists. -

The Baylor Lariat 10 Vol

ROUNDING UP CAMPUS NEWS SINCE 1900 THE BAYLOR LARIAT 10 VOL. 109 No. 42 FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2009 © 2009, Baylor University NEWS PAGE 4 BOOKS PAGE 6 SPORTS PAGE 8 Downtown in a DASH Friendly reading Bears enter new era See how one shuttle system Weekend sale will A3 starters are gone, but has fared since starting benefit libraries of BU is ready to hit the court operations this fall McLennan County and prove its power BU officials: Funds fine despite loss BY ADEOL A ARO areas of greatest need, as well STAFF WRITER as start new degree programs: [a] Ph.D. in business school, Baylor’s endowment has master’s of public health in decreased by 13.3 percent in community health, a new the past year because of the bachelor’s of science degree downturn in the global econ- for computer science fellows, omy. among others and other proj- According to university ects,” Fogleman said. officials, the endowment de- “For instance, one of the ar- creased from approximately eas of greatest need was geol- $1.05 billion dollars in June ogy...they’ve been able to add 2008 to $936 million dollars outstanding scholars, such as SARAH GROMAN | S TAFF PHOTO G RA P HER this year. Dr. Daniel Peppe, who came The last time the endow- to Baylor from Yale to serve as Dutton Dance Party ment decreased significantly an assistant professor of geol- was in 2003, when it dropped ogy.” Baylor Alumnus Logan Walter sings lead vocals for The Dutton Band. The band held a CD release concert at Common Grounds on from $584 million to $561 mil- Fogleman said that Baylor Thursday as a promotion for its latest album, “All Things Fade.” The band is originally from Waco, and began its successful career in lion. -

RADIO's DIGITAL DILEMMA: BROADCASTING in the 21St

RADIO’S DIGITAL DILEMMA: BROADCASTING IN THE 21st CENTURY BY JOHN NATHAN ANDERSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor John C. Nerone, Chair and Director of Research Associate Professor Michelle Renee Nelson Associate Professor Christian Edward Sandvig Professor Daniel Toby Schiller ii ABSTRACT The interaction of policy and technological development in the era of “convergence” is messy and fraught with contradictions. The best expression of this condition is found in the story behind the development and proliferation of digital audio broadcasting (DAB). Radio is the last of the traditional mass media to navigate the convergence phenomenon; convergence itself has an inherently disruptive effect on traditional media forms. However, in the case of radio, this disruption is mostly self-induced through the cultivation of communications policies which thwart innovation. A dramaturgical analysis of digital radio’s technological and policy development reveals that the industry’s preferred mode of navigating the convergence phenomenon is not designed to provide the medium with a realistically useful path into a 21st century convergent media environment. Instead, the diffusion of “HD Radio” is a blocking mechanism proffered to impede new competition in the terrestrial radio space. HD Radio has several critical shortfalls: it causes interference and degradation to existing analog radio signals; does not have the capability to actually advance the utility of radio beyond extant quality/performance metrics; and is a wholly proprietary technology from transmission to reception. -

Alternative 2020

Mediabase Charts Alternative 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 TWENTY ONE PILOTS Level Of Concern 2 BILLIE EILISH everything i wanted 3 AJR Bang! 4 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 5 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 6 ALL TIME LOW Monsters f/blackbear 7 ABSOFACTO Dissolve 8 POWFU Coffee For Your Head 9 SHAED Trampoline 10 UNLIKELY CANDIDATES Novocaine 11 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 12 MACHINE GUN KELLY Bloody Valentine 13 STROKES Bad Decisions 14 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 15 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 16 PANIC! AT THE DISCO High Hopes 17 KILLERS Caution 18 WEEZER Hero 19 TWENTY ONE PILOTS The Hype 20 WALLOWS Are You Bored Yet? 21 LOVELYTHEBAND Broken 22 DAYGLOW Can I Call You Tonight? 23 GROUPLOVE Deleter 24 SUB URBAN Cradles 25 NEON TREES Used To Like 26 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 27 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 28 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 29 LUMINEERS Life In The City 30 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 31 GREEN DAY Oh Yeah! 32 MARSHMELLO Happier f/Bastille 33 AWOLNATION The Best 34 LOVELYTHEBAND Loneliness For Love 35 KENNYHOOPLA How Will I Rest In Peace If... 36 BAKAR Hell N Back 37 BLUE OCTOBER Oh My My 38 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 39 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 40 BILLIE EILISH bad guy 41 MATT MAESON Cringe 42 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 43 PEACH TREE RASCALS Mariposa 44 IMAGINE DRAGONS Natural 45 ASHE Moral Of The Story f/Niall 46 DOMINIC FIKE 3 Nights 47 I DONT KNOW HOW BUT THEY.. -

Free Download

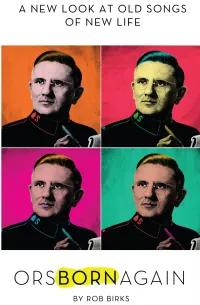

ORSBORNAGAIN a new look at old songs of new life by Rob Birks ORSBORNAGAIN Rob Birks 2013 Frontier Press All rights reserved. Except for fair dealing permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any means without written permission from the publisher. Birks, Rob ORSBORNAGAIN May 2013 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture references used in this text are from The Holy Bible, New International Version. THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. The King James Version is public domain in the United States. Scripture taken from The Message. Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Copyright © The Salvation Army USA Western Territory ISBN 978-0-9768465-8-1 Printed in the United States For my mother, Major Ruth Birks, who always hummed a tune as I was growing up, and who is herself one of God’s great poetic works & my Poet Father, Major Daniel H. Birks— always reading, always writing, always loving. iii Rob Birks has fittingly honored the enduring legacy of Albert Ors- born’s poetic brilliance, bringing the Salvation Army General’s timeless language into a modern context and adding commentary reflecting Birks’ own inimitable personality. I was blessed by this book, strength- ened and challenged in the reading to be a blessing to OTHERS. —Tom Walker, Social Services Secretary The Salvation Army Northwest Division A living faith will find its voice in contemporary idiom. We rightly em- brace in our worship ever fresh expressions of Spirit-inspired praise. -

The Complete Ask Scott

ASK SCOTT Downloaded from the Loud Family / Music: What Happened? website and re-ordered into July-Dec 1997 (Year 1: the start of Ask Scott) July 21, 1997 Scott, what's your favorite pizza? Jeffrey Norman Scott: My favorite pizza place ever was Symposium Greek pizza in Davis, CA, though I'm relatively happy at any Round Table. As for my favorite topping, just yesterday I was rereading "Ash Wednesday" by T.S. Eliot (who can guess the topping?): Lady, three white leopards sat under a juniper-tree In the cool of the day, having fed to satiety On my legs my heart my liver and that which had been contained In the hollow round of my skull. And God said Shall these bones live? shall these Bones live? And that which had been contained In the bones (which were already dry) said chirping: Because of the goodness of this Lady And because of her loveliness, and because She honours the Virgin in meditation, We shine with brightness. And I who am here dissembled Proffer my deeds to oblivion, and my love To the posterity of the desert and the fruit of the gourd. It is this which recovers My guts the strings of my eyes and the indigestible portions Which the leopards reject. A: pepperoni. honest pizza, --Scott August 14, 1997 Scott, what's your astrological sign? Erin Amar Scott: Erin, wow! How are you? Aries. Do you think you are much like the publicized characteristics of that sun sign? Some people, it's important to know their signs; not me.