Attraction, Affiliation and Disenchantment in a New Religious Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Malleability of Yoga: a Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 25 Article 4 November 2012 The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jain, Andrea R. (2012) "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 25, Article 4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1510 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Jain: The Malleability of Yoga The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis FOR over three thousand years, people have yoga is Hindu. This assumption reflects an attached divergent meanings and functions to understanding of yoga as a homogenous system yoga. Its history has been characterized by that remains unchanged by its shifting spatial moments of continuity, but also by divergence and temporal contexts. It also depends on and change. This applies as much to pre- notions of Hindu authenticity, origins, and colonial yoga systems as to modern ones. All of even ownership. Both Hindu and Christian this evidences yoga’s malleability (literally, the opponents add that the majority of capacity to be bent into new shapes without contemporary yogis fail to recognize that yoga breaking) in the hands of human beings.1 is Hindu.3 Yet, today, a movement that assumes a Suspicious of decontextualized vision of yoga as a static, homogenous system understandings of yoga and, consequently, the rapidly gains momentum. -

Themelios an International Journal for Pastors and Students of Theological and Religious Studies

Themelios An International Journal for Pastors and Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 2 Issue 3 May, 1977 Contents Karl Barth and Christian apologetics Clark H Pinnock Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism Vishal Mangalwadi The ‘rapture question’ Grant R Osborne Acts and Galatians reconsidered Colin J Hemer Book Reviews Vishal Mangalwadi, “Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism,” Themelios 2.3 (May 1977): 72- 77. Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism Vishal Mangalwadi [p.72] Man’s basic problem according to Hinduism is not moral but metaphysical. It is not that man is guilty of having broken God’s moral law, but that he has somehow forgotten his true nature and he experiences himself to be someone other than what he is. Man is not a sinner; he is simply ignorant of his true self. The problem is with his consciousness. His salvation consists in attaining that original state of consciousness which he has lost. Man’s true nature or original consciousness is defined differently by monistic and non-monistic gurus. The monistic gurus, who believe that God, man and the universe are ultimately one, teach that man is Infinite Consciousness or God, but has somehow been entangled in finite, personal, rational consciousness. So long as he remains in this state he is born repeatedly in this world of suffering. Salvation lies in transcending finite, personal consciousness and merging into (or experiencing ourselves to be) the Infinite Impersonal Consciousness, and thereby getting out of the cycle of births and deaths. In other words, salvation is a matter of perception or realization. -

History of Yoga 2

The History of Yoga by Christopher (Hareesh) Wallis (hareesh.org, mattamayura.org) 1. Yoga means joining oneself (yoga) firmly to a spiritual discipline (yoga), the central element of which is the process (yoga) of achieving integration (yoga) and full connection (yoga) to reality, primarily through scripturally prescribed exercises (yoga) characterized by the meta-principle of repeatedly bringing together all the energies of the body, mind, and senses in a single flow (ekāgratā) while maintaining tranquil focused presence (yukta, samāhita). 2. Yoga in the Indus Valley Civilization? 2500-1700 BCE [hardly likely!] 3. Yoga in the early Vedas? (lit., 'texts of knowledge,' 1800-800 BCE): not in the hymns (saṃhitās), but there are early yogic ideas in the priestly knowledge-books (brāhmaṇas and āraṇyakas) 4. Yoga in the śramana movement (600 – 300 BCE) A. the Buddha (Siddhārtha Gautama), 480 – 400 BCE B. Mahāvīra Jina, founder of Jainism, ca. 550 – 450 BCE 5. Yoga in the Upanishads (lit., 'hidden connections' 700 BCE -100 CE): key teachings A. "Thou art That" (tat tvam asi; Chāndogya Upanishad 6.8.7) • cf. "I am Brahman!" (aham brahmāsmi; Bṛhad-ārankaya Up. 1.4.10) • Practice (abhyāsa): SO’HAM japa B. "Two birds...nestle on the very same tree. One of them eats a tasty fig; the other, not eating, looks on." (Muṇḍaka Upanishad 3.1.1) • Practice: Witness Consciousness meditation C. "A divine Self (ātman) lies hidden in the heart of a living being...Regard that Self as God, an insight gained through inner contemplation." (Kaṭha Upanishad, ca. 200 BCE) • Practice: concentrative meditation. "When the five perceptions are stilled, when senses are firmly reined in, that is Yoga." • Practice: sense-withdrawal & one-pointedness D. -

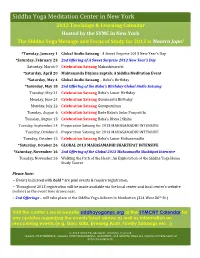

Siddha Yoga Meditation Center in New York

Siddha Yoga Meditation Center in New York 2013 Teachings & Learning Calendar Hosted by the SYMC in New York The Siddha Yoga Message and Focus of Study for 2013 is Mantra Japa! *Tuesday, January 1 Global Audio Satsang - A Sweet Surprise 2013 New Year’s Day *Saturday, February 23 2nd Offering of A Sweet Surprise 2013 New Year’s Day Saturday, March 9 Celebration Satsang Mahashivaratri *Saturday, April 20 Muktananda Dhyana Saptah: A Siddha Meditation Event *Saturday, May 4 Global Audio Satsang – Baba’s Birthday *Saturday, May 18 2nd Offering of the Baba’s Birthday Global Audio Satsang Tuesday, May 21 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Lunar Birthday Monday, June 24 Celebration Satsang Gurumayi’s Birthday Monday, July 22 Celebration Satsang Gurupurnima Tuesday, August 6 Celebration Satsang Bade Baba’s Solar Punyatithi Tuesday, August 13 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Divya Diksha Tuesday, September 24 Preparation Satsang for 2013 MAHASAMADHI INTENSIVE Tuesday, October 8 Preparation Satsang for 2013 MAHASAMADHI INTENSIVE Tuesday, October 15 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Lunar Mahasamadhi *Saturday, October 26 GLOBAL 2013 MAHASAMADHI SHAKTIPAT INTENSIVE *Saturday, November 16 2nd Offering of the Global 2013 Mahsamadhi Shaktipat Intensive Tuesday, November 26 Walking the Path of the Heart: An Exploration of the Siddha Yoga Home Study Course Please Note: ~ Events indicated with bold * are paid events & require registration. ~ Throughout 2013 registration will be made available via the local center and local center’s website (online) as the event time draws near. ~ 2nd Offerings – will take place at the Siddha Yoga Ashram in Manhattan (324 West 86th St.) Visit the center’s local website siddhayoganyc.org or the SYMCNY Calendar for any updates regarding the events listed above as well as information on reoccurring events (e.g. -

Branding Yoga the Cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga

ANDREA R. JAIN Branding yoga The cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga n October 1989, long-time yoga student, John Friend modern soteriological yoga system based on ideas and (b. 1959) travelled to India to study with yoga mas- practices primarily derived from tantra. The encounter Iters. First, he went to Pune for a one-month intensive profoundly transformed Friend, and Chidvilasananda in- postural yoga programme at the Ramamani Iyengar itiated him into Siddha Yoga (Williamson forthcoming). Memor ial Yoga Institute, founded by a world-famous yoga proponent, B. K. S. Iyengar (b. 1918). Postural yoga (De Michelis 2005, Singleton 2010) refers to mod- Friend spent the next seven years deepening his ern biomechanical systems of yoga, which are based understanding of both Iyengar Yoga and Siddha Yoga. on sequences of asana or postures that are, through He gained two Iyengar Yoga teaching certificates and pranayama or ‘breathing exercises’, synchronized with taught Iyengar Yoga in Houston, Texas. Every sum- 1 the breath. Following Friend’s training in Iyengar Yoga, mer, he travelled to Siddha Yoga’s Shree Muktananda he travelled to Ganeshpuri, India where he met Chid- Ashram in upstate New York, where he would study 1954 vilasananda (b. ), the current guru of Siddha Yoga, for one to three months at a time. at the Gurudev Siddha Peeth ashram.2 Siddha Yoga is a Friend founded his own postural yoga system, Anusara Yoga, in 1997 in The Woodlands, a high- 1 Focusing on English-speaking milieus beginning in end Houston suburb. Anusara Yoga quickly became the 1950s, Elizabeth De Michelis categorizes modern one of the most popular yoga systems in the world. -

The Siddha-Yoga to the Test of the Criticism

1 The Siddha-Yoga to the test of the criticism. by Bruno Delorme - April 2018 - Presentation: This reflection is the culmination of a project that has been close to my heart for a long time: to write about an Indian sect, Siddha-Yoga, to which I belonged in my late teens. It presents itself at the same time as a historical, sociological, and psychoanalytic analysis. I wanted to put at the beginning my personal testimony which opens the reflection, and this in order to show how this movement affected me at a certain period of my life, and what it also produced in me. A Summary at the end of the article allows you to identify the main chapters. 2 My passage in the movement of Siddha-Yoga. Testimony by Bruno Delorme1 It was during the year 1978, when I was starting my professional life and after repeated school failures, that I became acquainted with Siddha-Yoga. My best friend at the time was involved in it and so talked to me about it at length. We were both in search of meaning in our lives and in search of spirituality. And Siddha-Yoga suddenly seemed to offer us what we had been looking for a long time. I joined the movement a year after him, and I discovered it through two communities that were roughly equidistant from the city where I lived: the Dijon ashram and the Lyon ashram. The latter was headed by A. C. and his wife, better known today for having managed the association "Terre du Ciel" and its magazine. -

A Short Description of Maha Yoga

A Short Description of Maha Yoga The Simple, Easy and Free Path to Self-Realization What is Maha Yoga? All human beings have three distinct elements – body, mind and spirit. All of us are aware of our bodies, and most of us are aware of our minds. However, far too many of us are unaware of the spirit that resides in each one of us. Our normal awareness often extends only to our bodies and to our minds. Only rarely do some of us get the experience of being actually aware of our own spiritual existence. The objective of Yoga is to extend our Awareness beyond our bodies and our minds to the spirit (Prana), the Universal Life Energy (Chaitanya Shakti) that lies dormant in each and every one of us. When our Awareness merges with the Chaitanya we get happiness and satisfaction in all aspects of our lives, eventually leading to eternal bliss. This union of our Awareness with the Chaitanya is the true meaning of the term Yoga, which means “union” in Sanskrit. The dormant sliver of Chaitanya Shakti, which resides in all of us, is referred to in Yoga terminology as the Kundalini Shakti (Kundalini Energy). Since our brains are usually chockfull of the physical and mental clutter of our day-to-day lives, the Kundalini in most of us gets pushed to the opposite end of our nervous system, the base of our spine (Mooladhara Chakra). There it lies dormant in its subtle form leaving most of us completely unaware of its existence throughout our lives. -

Schisms of Swami Muktananda's Siddha Yoga

Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 15 (2010) Schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga John Paul Healy Abstract: Although Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga is a relatively new movement it has had a surprising amount of offshoots and schismatic groups claiming connection to its lineage. This paper discusses two schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga. These are proposed as important schisms from Siddha Yoga because both swamis held senior positions in Muktananda’s original movement. The paper discusses the main episodes that appeared to cause the schism within Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga and the subsequent growth of Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga. Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga may be considered as schisms developing from a leadership dispute rather than doctrinal differences. These groups may also present a challenge to Gurumayi’s Siddha Yoga as sole holder of the lineage of Swami Muktananda. Because of movements such as Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga, Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga Practice continues and grows, although, it is argued in this paper that it now grows through a variety of organisations. Introduction Prior to Swami Muktananda’s death in 1982 Swami Nityananda was named his successor to Siddha Yoga; by 1985 he was deposed by his sister and co-successor Gurumayi. Swami Shankarananda, a senior Swami in Siddha Yoga, sympathetic to Nityananda also left the movement around the same time. However, both swamis with the support of devotees of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, developed their own movements and today continue the lineage of their Guru and emphasise the importance of the Guru Disciple relationship within Swami Muktananda’s tradition. -

V Edictradition S Hramanatradition

V e d i c t r a d i t i o n S h r a m a n a t r a d i t i o n Samkhya Buddhism ―Brahmanas‖ 900-500 T a n t r a BCE Jainism ―Katha ―Bhagavad Upanishad‖ Gita‖ 6th Century 5th—2nd BCE ―Samkhya Century BCE Karika‖ Patnanjali’s Yogachara ―Tattvarthasutra‖ Buddhism 200 CE ―Sutras‖ 2nd Century CE Adi Nanth 4th –5th (Shiva?) 100 BCE-500CE Century CE The Naths Matsyendranath ―Hatha Yoga‖ Raja ―Lord of Fish‖ (Classical) Yoga Helena Guru Nanak Dev Ji Gorakshanath Blavatsky ―Sikhism‖ ―Laya Yoga‖ b. 8th century 15th Century ―Theosophists‖ “Hatha Yoga Pradipika” Annie by Yogi Swatmarama Besant 16th Centruy Charles Leadbeater ―The Serpent Power‖ Krishnanand Babu Saraswati Bhagwan Das British John Woodroffe Mahavatar Babaji Gymnastics (Arthur Avalon) (Saint?) Late 19th/early 20th century Bhagavan Ramakrishna Vivekananda ―Kriya Yoga‖ Nitkananda Vishnu Vishwananda B. 1888 b. 1863 Yoga ―Krama Vinyasa‖ Bhaskar Lele Saraswati Kurunta Dadaji Ramaswami Lahiri Mahasaya Brahmananda ―World’s ―Siddha Paliament on Yoga‖ Saraswati Bengali Mahapurush Religion‖ B. 1870 Maharaj ―Integral Yoga‖ Baba Muktananda Krishnamurti B. 1908 A.G. Krishnamacharya B. 1895 Sri Sivananda Yukteswar Giri Nirmalanda Auribindo Mirra Ghandi Mohan B. 1888 B. 1872 Alfassa B. 1887 ―Transcendental Swami ―Kundalini ―Divine Meditation‖ Chidvilasananda Kailashananda Indra Yoga‖ 1935 Life Desikachar Devi Swami Society‖ Yogananda Maharishi (son) Kripalvananda Sri Mahesh Yogi Auribindo b. 1893 ―viniyoga‖ b. 1913 Asharam Bishnu Ghosh ―Ashtanga Yogi ―Autobiography Dharma Mittra Gary Yoga‖ ―Light of a Yogi‖ (brother) Mahamandaleshwar Kraftsow BKS on Bhajan Nityandanda b. 1939 Patabhi Jois Iyengar Yoga‖ b. -

Chapter 2: the Guru Darshan (From the Eternal One)

Chapter 2: The Guru Darshan Searching for the Sadguru with total devotion and longing leads to success in locating Him. In this chapter, amongst other details, I will also describe the circumstances under which various devotees met Bhagavan Nityananda and realized that he was their Guru. Pitfalls in the path Once, a lady visited our home at Vajreshwari. She appeared to be very pious and her looks resembled an ascetic. She wore an ochre saree, left her hair loose and adorned her forehead with a very large vermilion tika. The ladies of my house were pleased at her impressive presence and got overwhelmed by her elaborate sermons. Her entry into our house was instantaneous and the members of the family treated her with the respect due to a visiting saint. She performed some miracles, including materializing kumkum in her palm. All the womenfolk were mesmerized by her charisma and surrendered to her demands. However, one fine morning the lady disappeared as dramatically as she had appeared, and so did some of our valuables. There was no trace of her. The family was saddened that a stranger could dupe them so easily. Within no time, our family rushed to have the darshan of Bhagavan Nityananda. Baba was staying at Vaikuntha at that time. The moment they stepped inside the hall, Baba muttered, “Bunch of fools. Trusting all and sundry! Blindly watching a magic show!” They all felt ashamed. After having a Guru of Baba’s stature, it was indeed very stupid to get carried away by someone who performed so called ‘miracles’. -

Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies

iii ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK OF YOGA AND MEDITATION STUDIES Edited by Suzanne Newcombe and Karen O’Brien- Kop First published 2021 ISBN: 978- 1- 138- 48486- 3 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 351- 05075- 3 (ebk) 27 OBSERVING YOGA The use of ethnography to develop yoga studies Daniela Bevilacqua (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 647963 (Hatha Yoga Project)). 393 2 7 OBSERVING YOGA 1 Th e use of ethnography to develop yoga studies D a n i e l a B e v i l a c q u a Introduction Ethnography as a method can be defi ned as an approach to social research based on fi rst- hand experience. As a methodology, it intends to create an epistemology that emphasises the signifi - cance and meaning of the experiences of the group of people being studied, thereby privileging the insider’s view. A researcher using ethnography employs mostly qualitative methods (Pole and Morrison 2003: 9), such as interviews (that can be non- structured, structured or casual con- versation), participant observation, fi eld notes, etc. Participant observation can be considered as a distinctive feature of ethnography; within this method the researcher adopts a variety of positions. As Atkinson and Hammersley have noted ( 1994 : 248), the researcher can be: a complete observer when the researcher is a member of the group being studied who conceals his/ her researcher role; an observer as participant when s/ he is a member of the group being studied and the group is aware of the research activity; a participant as observer when s/ he is not a member of the group but is interested in par- ticipating as a means for conducting better observation; or a participant non-member of the group who is hidden from view while observing. -

Chapter 3: the Guru Leela, Part a (The Eternal One)

Chapter 3: The Guru Leela, Part A At Palani Young Nityananda once visited the ancient city of Palani in the then state of Madras in South India. There is a famous Murugan temple over a hill. The priest of the temple was just returning after locking the doors of the temple following the afternoon puja. Young Nityananda accosted the priest and demanded that the temple door be reopened for him. The priest was astonished by the audacity of this young lanky youth. He was a head priest and nobody should dare to make such a request, at least not a young lad. The priest refused to oblige and was a bit nasty to Nityananda. Nityananda appeared not to be bothered by the priest’s reply and just walked towards the temple. As the priest reached the foot of the hill he heard the temple bells ringing. The sound came distinctly from his temple, which he had just locked. The priest got worried and wondered how the bells could ring from the closed temple. In the temple there was lot of gold and other precious articles. He retraced his steps back to the temple. The door was locked, yet the bells were ringing! He hurriedly opened the doors and entered the inner temple. There was nobody there and the bell had stopped ringing. When he looked at the deity to confirm whether the gold on the statue was safe, he was shocked to find the young lanky lad in its place. Wherever Nityananda went in Palni, money used to pour. He stood at the foot of the hill and the pilgrims visiting the temple placed money at his feet.