William Shakespeare's King Lear by William Shakespeare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JBC Book Clubs Discussion Guide Created in Partnership with Picador Jewishbookcouncil.Org

JBC Book Clubs Discussion Guide Created in partnership with Picador Jewishbookcouncil.org Jewish Book Council Contents: 20th Century Russia: In Brief 3 A Glossary of Cultural References 7 JBC Book Clubs Discussion Questions 16 Recipes Inspired by The Yid 20 Articles of Interest and Related Media 25 Paul Goldberg’s JBC Visiting Scribe Blog Posts 26 20th Century Russia: In Brief After the Russian Revolution of 1917 ended the Czar- Stalin and the Jews ist autocracy, Russia’s future was uncertain, with At the start of the Russian Revolution, though reli- many political groups vying for power and ideolog- gion and religiosity was considered outdated and su- ical dominance. This led to the Russian Civil War perstitious, anti-Semitism was officially renounced (1917-1922), which was primarily a war between the by Lenin’s soviet (council) and the Bolsheviks. Bolsheviks (the Red Army) and those who opposed During this time, the State sanctioned institutions of them. The opposing White Army was a loose collec- Yiddish culture, like GOSET, as a way of connecting tion of Russian political groups and foreign nations. with the people and bringing them into the Commu- Lenin’s Bolsheviks eventually defeated the Whites nist ideology. and established Soviet rule through all of Russia un- der the Russian Communist Party. Following Lenin’s Though Stalin was personally an anti-Semite who death in 1924, Joseph Stalin, the Secretary General of hated “yids” and considered the enemy Menshevik the RCP, assumed leadership of the Soviet Union. Party an organization of Jews (as opposed to the Bolsheviks which he considered to be Russian), as Under Stalin, the country underwent a period of late as 1931, he continued to condemn anti-Semitism. -

Cordelia''s Portrait in the Context of King Lear''s

Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez Cordelias Portrait in the Context of King Lears... 181 CORDELIAS PORTRAIT IN THE CONTEXT OF KING LEARS INDIVIDUATION* Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez** Abstract: This analysis attempts to show the relations between the individual psyche and the contents of the collective unconscious. Following Von Franzs analytical technique, the tragic action in King Lear will be read as an individuation process that will rescue archetypal contents and solve existential paradoxes that cause an imbalance between the ego and the self, leading to self-destruction. Once communication is eased and balance is restored, the transformation-seeking process that engaged the design of the play itself becomes resolved, and events can be led to a conventional tragic resolution. Jungian analysis will therefore provide a critical framework to unveil the subconscious contents that tear the character of the king between annihilation and survival, the anima complex that affects the king, responding thus for the action of the play and its centuries-old success. Keywords: collective unconscious, myth, individuation, archetype, tragedy, anima. Resumen: Este análisis pretende sacar a la luz las relaciones entre la psyche individual y los contenidos del inconsciente colectivo. Siguiendo la técnica analítica de Von Franz, la acción trágica de King Lear será entendida a través del proceso de individuación que revierte sobre los contenidos arquetípicos y resuelve las paradojas existenciales que cau- san el desequilibrio entre ego y self. Una vez que la comunicación es facilitada y el equilibrio psíquico recuperado, el proceso transformativo que afecta la génesis de la trama se resuelve y el argumento alcanza una resolución convencional. -

Sources of Lear

Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Lynne Bradley, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) Abstract The temptation to meddle with Shakespeare has proven irresistible to playwrights since the Restoration and has inspired some of the most reviled and most respected works of theatre. Nahum Tate’s tragic-comic King Lear (1681) was described as an execrable piece of dementation, but played on London stages for one hundred and fifty years. David Garrick was equally tempted to adapt King Lear in the eighteenth century, as were the burlesque playwrights of the nineteenth. In the twentieth century, the meddling continued with works like King Lear’s Wife (1913) by Gordon Bottomley and Dead Letters (1910) by Maurice Baring. -

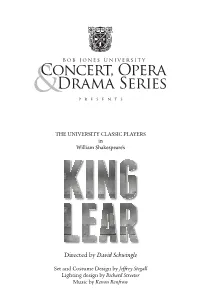

Directed by David Schwingle

THE UNIVERSITY CLASSIC PLAYERS in William Shakespeare’s Directed by David Schwingle Set and Costume Design by Jeffrey Stegall Lighting design by Richard Streeter Music by Kenon Renfrow CAST OF CHARACTERS DIRECTOR’S NOTES Lear, King of Britain ......................................................................... Ron Pyle It is a fearful thing to write about Shakespeare (brief let me be!). The fear increases when one approaches the Goneril, Lear’s eldest daughter ............................................................... Erin Naler towering achievement that is King Lear. The wheel turns a bit more toward a paralyzed state if one considers Duke of Albany, Goneril’s husband ................................................... Harrison Miller the laden, ceremonial barge of relevant scholarship on the subjects. (Imagine entering a room and seeing Oswald, Goneril’s steward ............................................................. Nathan Pittack the eminent Shakespeare scholar, Emma Smith, or our local Spenser and Shakespeare scholar, Ron Horton, Regan, Lear’s second daughter ............................................................ Emily Arcuri comfortably seated, smiling at you!) And yet, though surrounded by giants on every side, some of Lear’s own Duke of Cornwall, Regan’s husband ..................................................... Alex Viscioni making, King Lear pushes on, so I’ll push on and pen a few words about Lear, language, and love. Cordelia, Lear’s youngest daughter .................................................... -

Akira Kurosawa's Lear: Ran and the Failure of the Samurai Ethic

1 Akira Kurosawa’s Lear: Ran and the Failure of the Samurai Ethic “Cineaste: You mentioned in an interview in a Japanese magazine that in Ran you wanted to depict a man’s karma from a “heavenly” viewpoint. Will you elaborate? Akira Kurosawa: I did not exactly say that. Japanese reporters always misunderstand or conveniently summarize what I really say. What I meant was that some of the essential scenes of this film are based on my wondering how God and Buddha, if they actually exist, perceive this human life, this mankind stuck in the same absurd behavior patterns. Kagemusha is made from the viewpoint of one of Kagemusha [shadow warrior—ed.] who sees the specific battles which he is involved in, and moreover the civil war period in general, from a very circumscribed point of view. This time, in Ran, I wanted to suggest a larger viewpoint . more objectively. I did not mean that I wanted to see through the eyes of a heavenly being. I believe that the world would not change even if I made a direct statement: do this and do that. Moreover, the world will not change unless we steadily change human nature itself and our very way of thinking. We have to exorcise the essential evil in human nature, rather than presenting concrete solutions to problems or directly depicting social problems. Therefore, my films might have become more philosophical.” + + + Just as Kurosawa reworked Shakespeare’s Macbeth in his Throne of Blood and reworked the main themes and characters of Hamlet in The Bad Sleep Well, Kurosawa in the last phase of his career chose to rework King Lear in his film Ran (or “Chaos”). -

Descendants of Llyr King Lear

Descendants of Llyr King Lear Generation 1 1. LLYR KING1 LEAR was born in 10 AD in Abt,,British Columbia,Canada. He died in 10 AD in AD,,,. He married PENARDIM CELTIC. She was born in Judea, , British Columbia, Canada. Llyr King Lear and Penardim Celtic had the following child: 2. i. BRAN THE2 BLESSED (son of Llyr King Lear and Penardim Celtic) was born in 21 AD in Monmothshire, , , England. He died in 1936 in Monmothshire, , , England. He married ENYGEUS BEN JOSEPH. She was born in Ad, Maluku, Indonesia. She died in Ely, Cambridgeshire, , England. Generation 2 2. BRAN THE2 BLESSED (Llyr King1 Lear) was born in 21 AD in Monmothshire, , , England. He died in 1936 in Monmothshire, , , England. He married ENYGEUS BEN JOSEPH. She was born in Ad, Maluku, Indonesia. She died in Ely, Cambridgeshire, , England. Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph had the following children: 3. i. CARADOC THE3 SILURES (son of Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph) was born in Trevan, Llanilid, Glamorganshire, England. He died in Avalon, Cape May, New Jersey, United States. He married LIVING VENISSA. ii. CARADOC CARACTACUS OF SILURIA (son of Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph) was born in 1980 in Siluria, , , England. He died in 1954 in Rome, Roma, Lazio, Italy. iii. KING OF THE SILURES CARADOC (son of Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph) was born in 65 AD in Trevan,Llanilid,Glamorganshire,. He died in Rome,,,. Generation 3 3. CARADOC THE3 SILURES (Bran The2 Blessed, Llyr King1 Lear) was born in Trevan, Llanilid, Glamorganshire, England. -

1 on King Lear and the “Avoidance of Love” Alan Baily Stephen F. Austin State University I. the World and the Stage the Worl

On King Lear and the “Avoidance of Love” Alan Baily Stephen F. Austin State University I. The World and the Stage The Worldly Poet Shakespeare is our most worldly poet. This much seems to be a point of convergence among critics. But what does this mean? For Thomas Carlyle it meant that Shakespeare’s poetry was “broad” rather than “deep”. Shakespeare was a poet of the world, rather than a world. By contrast, Dante exemplified a “deep” poet. The final referent of Dante’s poetry was not the world but eternity, and his world vision was distinctly that of the medieval epoch. Dante’s greatness was to refined this vision to the point of perfection. For Carlyle, this was partially a result of Dante’s political misfortune, which occasioned in his earthly homelessness. “The earthly world had cast [Dante] forth, to wander, wander; no living heart to love him now; for his sore miseries there was no solace here.” The deeper naturally would the Eternal World impress itself on him; that awful reality over which, after all, this Time-world, with its Florences and banishments, only flutters as an unreal shadow. Florence thou shalt never see: but Hell and Purgatory and Heaven thou shalt surely see! What is Florence, Can della Scala, and the World and Life altogether? ETERNITY: thither, of a truth, not elsewhither, art thou and all things bound! The great soul of Dante, homeless on earth, made its home more and more in that awful other world. Carlyle describes the “depth” of Dante’s vision by reference to the poet’s psychological “intensity.” To the modern eye, Dante’s seems “a narrow, and even sectarian mind: it is partly the fruit of his age and position, but partly too of his own nature. -

King Lear and the Catholic Drama of Three Households and Four Loves

Ken Colston King Lear and the Catholic Drama of Three Households and Four Loves “That word love, which greybeards call divine.” henry vi, part iii Hardly anyone now reads the world’s greatest work of literature for its dramatization of Catholic wisdom. By the 1960s, according to R. A. Foakes, critical opinion had crowned King Lear as Shake- speare’s greatest play, and it is still indeed common to hear it main- tained that Lear is the greatest work of literature ever written in any language. Foakes attributes this rise mainly to the apocalyptic and nihilistic mood of the Cold War. And yet during the same period, he points out, the accepted reading of Lear changed from that of a play concerned with a “pilgrimage to redemption” to one offering “Shake- speare’s bleakest and most despairing vision of suffering, all hints of consolation undermined or denied.”1 It is not surprising that a nihilistic, skeptical age would see only nihilism and skepticism in King Lear. To be sure, the play has some of the ugliest, darkest minutes in all of literature: two ungrateful daugh- ters strip their aged father of his property and drive him outdoors unprotected into a raging storm as he declines into raving madness; a betrayed spy of the state has both eyes gouged out on stage, one logos 16:4 fall 2013 16 logos in cruel jest; a father reconciled to his only loving daughter finds her hanged right after their reconciliation, and another father suffers from a broken heart when he learns that he has wronged his loving son; throughout it all, the cosmic order seems indifferent and even hostile. -

The Tragedy of King Lear

The Tragedy of King Lear by William Shakespeare An Electronic Classics Series Publication 2 The Tragedy of King Lear is a publication of The Elec- tronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any pur- pose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any respon- sibility for the material contained within the docu- ment or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. The Tragedy of King Lear by William Shakespeare, The Electronic Classics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU- Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Docu- ment File produced as part of an ongoing publica- tion project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Depart- ment of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Copyright © 1997 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity University. 3 The Tragedy of KING LEAR by William Shakespeare: His true Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King Lear and his three daughters. With the unfortunate life of Edgar, sonne and heire to the Earle of Gloster, and his sullen and assumed humor of Tom of Bedlam: 4 DRAMATIS PERSONAE LEAR, King of Britain KING OF FRANCE DUKE OF BURGUNDY DUKE OF CORNWALL DUKE OF ALBANY EARL OF KENT EARL OF GLOUCESTER EDGAR: Son to Gloucester. -

King Lear and Ran: Japanese Film in the English Literature Classroom

King Lear and Ran Japanese Film in the English Literature Classroom BY JAMES R. KEATING eachers often use film to help them present complex sub- jects in their high school classes. Unfortunately, many T films designed for classroom use are not as interesting as commercial productions—and many commercial films are not appropriate for the classroom! A good film is one that students will watch. It must look and sound better than a monotone rendering of a textbook. To engage a Language Arts class, the vehicle itself—the film—must be noteworthy. In English Literature, one of the great classics is, of course, ppon Herald Films Inc. (Tokyo) Shakespeare’s King Lear. Most teachers show all or part of various film versions of the play, but students say they don’t work very well. They feel the acting is stiff and the language difficult, dense, and strangely unfamiliar. But don’t give up! There is a film that students will embrace—Akira Kurosawa’s Ran—a Japanese telling of the Lear story and one of the best catalysts for the study of English and Asian culture in an interdisciplinary format. Akira Kurosawa (1910–98), one of Japan’s finest artists, pro- duced an astonishing number of films including Seven Samurai, Rash¬mon, The Hidden Fortress, and Throne of Blood, his stun- © 1985 Greenwich Film Production S. A. Paris/Herald Ace Inc./Ni Art and Design © 1998 Fox Lorber Home Video. ning, highly acclaimed adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. He was known for his use of rich visual imagery borrowed from Japanese theater, painting, music, and dance. -

1 King Lear, the Taming of the Shrew, a Midsummer Night's Dream, and Cymbeline, Presented by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Fe

King Lear, The Taming of the Shrew, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Cymbeline, presented by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, February-November 2013. Geoff Ridden Southern Oregon University [email protected] King Lear. Director: Bill Rauch. With Jack Willis/Michael Winters (King Lear), Daisuke Tsuji (Fool), Sofia Jean Gomez (Cordelia), and Armando Durán (Kent). The Taming of the Shrew. Director: David Ivers. With Ted Deasy (Petruchio), Neil Geisslinger (Kate), John Tufts (Tranio), and Wayne T. Carr (Lucentio). Cymbeline. Director: Bill Rauch. With Daniel José Molina (Posthumus), Dawn-Lyen Gardner (Imogen), and Kenajuan Bentley (Iachimo). A Midsummer Night's Dream. Director: Christopher Liam Moore. With Gina Daniels (Puck), and Brent Hinkley (Bottom). This was the 78th season of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and four of its eleven productions were Shakespeare plays: two were staged indoors (King Lear and The Taming of the Shrew) and two outdoors on the Elizabethan Stage/Allen Pavilion. This was the first season in which plays were performed indoors across the full season, and so both The Taming of the Shrew and King Lear had large numbers of performances. Nevertheless, according to the Mail Tribune, the non-Shakespeare plays drew larger audiences than Shakespeare this season: the plays staged outdoors fared especially poorly, and this is explained in part by the fact that four outdoor performances had to be cancelled because of 1 smoke in the valley, resulting in a loss of ticket income of around $200,000.1 King Lear King Lear was staged in the Thomas Theatre (previously the New Theatre), the smallest of the OSF theatres, and ran from February to November. -

Sederi 29 (2019: 221–26) Reviews Differently, with a Focus on Indianization

Poonam Trivedi and Paromita Chakravarti, eds. 2018 Shakespeare and Indian Cinemas: Local Habitations New York: Routledge Rosa García-Periago Queen’s University, Belfast, UK Poonam Trivedi and Paromita Chakravarti’s Shakespeare and Indian Cinemas: Local Habitations (2018) is a more-than-welcome addition to the field of Shakespeare film scholarship. It is a superb and groundbreaking collection that aims to explore Shakespeare on the Indian screen beyond Bollywood cinema. Thus, it moves away completely from previous research on Indian Shakespeares, which mainly focused on Bollywood cinema, Bollywood Shakespeares (Dionne and Kapadia 2014) being a case in point. Numerous articles and chapters have been devoted to this field. Jonathan Locke Hart’s latest collection Shakespeare and Asia (2019) includes for instance a chapter on Goliyon ki Rasleela Ram Leela (a Bollywood movie based on Romeo and Juliet) and Jonathan Gil Harris’ Masala Shakespeare (2018) discusses several Bollywood Shakespearean adaptations throughout. Those essays that have gone beyond Bollywood Shakespeares have mostly focused on Vishal Bhardwaj’s trilogy, either regarded as challenging Bollywood conventions (García-Periago 2014) or examples of “auteur” films (Burnett 2013). However, the way Shakespeare has been used or reinterpreted in Indian regional cinemas has been quite scarce and limited. Burnett’s Shakespeare and World Cinema (2013) is one of the few instances with a chapter on the southern Indian filmmaker Jayaraj. Hence, this book opens uncharted territory, exploring in depth Shakespeare’s presence outside the Bollywood arena, and claims for more visibility of regional cinemas. Trivedi and Chakravarti’s collection is precisely distinctive in its emphasis on regionalism for further research in the relations between Indian film and Shakespeare.