Religious Freedom Versus Sexual Expression: a Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEEDING the HUNGRY, Page 6 the 2 - Catholic Witness • September 14, 2018

The C150atholicWitness The Newspaper of the Diocese of Harrisburg September 14, 2018 Vol. 52 No. 18 March 2, 2018 Prayer Vigil 7:00 P.M. at Holy Name of Jesus Church, Harrisburg. This will includeFeeding a live enactment ofthe the Sorrowful Hungry Mysteries of the Rosary by young Ourpeople Daily from throughoutBread theServes Diocese, similarMeals, in many Fellowship ways to the Living inWay York of the Cross. This event will replace the traditional Palm Sunday Youth Mass and Gathering for 2018. All are welcome and encouraged to attend. March 3, 2018 Opening Mass for the Anniversary Year 10:00 A.M. at Holy Name of Jesus Church, Harrisburg. Please join Bishop Gainer as celebrant and Homilist to begin the anniversary year celebration. A reception, featuring a sampling of ethnic foods from various ethnic and cultural groups that comprise the faithful of the Diocese, will be held immediately following the Mass. August 28-September 8, 2018 Pilgrimage to Ireland Join Bishop Gainer on a twelve-day pilgrimage to the Emerald Isle, sponsored by Catholic Charities. In keeping with the 150th anniversary celebration, the pilgrimage will include a visit to the grave of Saint Patrick, the Patron Saint of the Diocese of Harrisburg. Participation is limited. November 3, 2018 Pilgrimage to Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception SAVE THE DATE for this diocesan pilgrimage to the Basilica in Washington,CHRIS HEISEY, THE CATHOLIC WITNESS Our Daily Bread soup kitchen in York serves an average of 275 meals a day to the hungry. The ministry is an outreach of 60 churches and synagogues, and was formed from theD.C. -

A Strategy for a Successful Christian Sexual Education Ministry in the African American Church

LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY A STRATEGY FOR A SUCCESSFUL CHRISTIAN SEXUAL EDUCATION MINISTRY IN THE AFRICAN AMERICAN CHURCH A THESIS PROJECT SUBMITTED TO LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY DARRYL L. JONES ATLANTA, GEORGIA April, 2011 Copyright © 2011 Darryl L. Jones All Rights Reserved ii A STRATEGY FOR A SUCCESSFUL CHRISTIAN SEXUAL EDUCATION MINISTRY IN THE AFRICAN AMERICAN CHURCH THESIS PROJECT APPROVAL SHEET ______________________________ GRADE ________________________ _____ MENTOR, Dr. Charles Davidson Title _______________________ READER, Dr. David W. Hirschman Associate Dean, Seminary Online Assistant Professor of Religion iii This dissertation is dedicated to: The grace of God, My Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, and the guidance of the Holy Spirit whom has been with me even when it did not seem like it… My unconditionally loving wife, Tisa, who believed in me and encouraged me with love and support... I love you so much!!! My children, April, Darryl II “DJ”, Michael and Kennedy, for being the best children I could ever ask for… My mom, Louise for working so hard to give me all you could so I could succeed… My sister Darsha who is so close to me people think we are twins… My grandmom, Ida Kate Bridges (Mudear) for raising me in a Christian home and showing me the importance of putting God first in my life, and for being my lifelong prayer warrior! My aunts, Vickie, Joan, Neicy for supporting me during my early years when your love for me was more than you can imagine… My uncle, Milton, who has been more like my big brother and probably, was the birth of this project for what he taught me during my youth… My extended family and friends who are so many to name… My pastoral shepherds Bishop William P. -

Clergy Sexual Abuse

CLERGY SEXUAL ABUSE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED SOURCES RELATED TO CLERGY SEXUAL ABUSE, ECCLESIASTICAL POLITICS, THEOLOGY AND CHURCH HISTORY Thomas P. Doyle Revised May 3, 2015, 2015 1 CONTENTS SEXUAL ABUSE BY CLERGY: BOOKS ..................................................................................3 SEXUAL ABUSE BY CLERGY: ARTICLES .........................................................................15 TOXIC RELIGION, NON-BELIEF AND CLERICALISM ...................................................23 THEOLOGICAL AND GENERAL: BOOKS ..........................................................................30 THEOLOGICAL AND GENERAL: ARTICLES ....................................................................40 SOCIOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION: BOOKS .............................................43 CANON LAW: BOOKS ..............................................................................................................46 CANON LAW: ARTICLES .......................................................................................................48 CANON LAW AND PROPERTY OWNERSHIP: ARTICLES .............................................54 CIVIL LAW: BOOKS .................................................................................................................56 CIVIL LAW: ARTICLES ...........................................................................................................57 HISTORY: BOOKS ....................................................................................................................66 -

Thomas Keating

RESOURCES FOR CONTEMPLATIVES INDEX Page 23 Page 20 Page 24 Page 7 Page 11 Page 5 WELCOME Page 13 Page 17 Page 15 Page 9 Page 16 Page 8 We promote reading as a Dear Reader, Index time-tested discipline for We are excited to introduce a new book: Contemplation and Community. n New . 4 focus and enlightenment. Along with it we have chosen other books that might be of interest to you. Please also visit www.contemplation-and-community.net n Teachers . 6 We help authors shape, Thomas Keating, Beatrice Bruteau, Richard Rohr, Laurence Freeman, Joan Chittister, clarify, write, and effectively You are invited to these special discounts through January 6, 2020 when you John Main, David Steindl-Rast promote their ideas. order directly at www.crossroadpublishing.com or send us an email with your order to [email protected] n Practices . 12 We conceive, create, and Contemplation, Meditation, Ignatian Spirituality, Lectio Divina, Jesus Prayer, Labyrinth, Fasting PLEASE USE PROMO CODE: 30Fall19 to receive at 30% discount distribute books. n Foundations . 17 We would love to hear your feedback at: www.crossroadpublishing.com/ Desert Fathers, Benedictine Spirituality Our expertise and passion crossroad/content/please-leave-comment is to provide healthy n Jesus . 18 spiritual nourishment in With best wishes, n Conversations . 20 written form. Your friends at The Crossroad Publishing Company n Recent and Noteworthy . 22 n Lives . 25 n Classics . .. 27 n Mysticism . 28 n Offerings . 31 2 WWW .CONTEMPLATION-aNd-commUNITY .NET WWW .CROSSroADPUBLISHING .COM 3 A Gathering of Fresh Voices Just Published “This vital and essential volume is for readers who sense that the evolution of individuals, Jessica M . -

Views of Selected Puritans, 1560-1630, on Human Sexuality

VIEWS OF SELECTED PURITANS, 1560-1630, ON HUMAN SEXUALITY by Jonathan Toussaint A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities in the History Department of the University of Tasmania. November, 1994. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION A. What Were the Original Puritans Like? 1 B. Sex in the Middle Ages 3 C. The Puritan Rejection of the Medieval Attitude 5 D. The Scope of the Thesis ' 7 CHAPTER 2: PURITAN ATTITUDES TOWARD THE SEXUAL ASPECTS OF MARRIAGE A. The Goodness of Sex in Marriage 17 B. The Nature of Sex 20 C. The Purpose of Marriage and Sex 22 D. Romantic Love as the Context for Sex 24 E. Techniques of Coitus 28 (i) Where 29 (ii) When 30 (iii) Healthfulness of Ejaculation 31 (iv) Sex-Play 33 (v) Coital Positions 35 (vi) Abstentions from Coitus 37 CHAPTER 3: PURITAN ATTITUDES TOWARD SOME ASPECTS OF SEXUAL DEVIATION A. Puritan Awareness· of Sexual Deviation 41 B. Adultery 44 C. Prostitution 48 D. Incest 53 E. Homosexuality 55 F. Masturbation 57 G. Pornography 58 CHAPTER 4: CONCLUSION 60 1 CHAPTERl INTRODUCTION A. WHAT WERE THE ORIGINAL PURITANS LIKE? A Puritan is someone who is afraid that somewhere, sometime, somebody is enjoying himself.1 A Puritan is a man sitting on a rock sucking a pickle contemplating adultery while reading the Bible. A Puritan is a blue nose who is against smoking, gambling, drinking, and sex. The revolution in sexual morality today is partly a reaction against Puritan sexual mores. These statements reflect an attitude toward a movement that has been assigned the posture of being sexually strict and repressive. -

Sex and the Church

Religious Teaching on Relationships and Families Sex and the Church We are going to watch a BBC Two programme, Sex and the Church, where we will learn about how Jesus was considered a social radical in his time by insisting on monogamy and no divorce. Task: as we watch, complete the True or False activity. If false, right the correct answer below in the space provided. True / False 1. Growing up in Galilee, Jesus was surrounded by Greek, Roman, and Jewish culture, so he would have been aware of the contradictory attitudes towards sex within the Middle East at the time. ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ True / False 2. Jesus’ attitude towards sex was typical of the time he lived in – the majority of people believed in monogamy (only having one partner) and not getting divorced. ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ True / False 3. Jesus’ treatment of women was radical at the time, playing important roles within his ministry, including female disciples who were largely socially excluded. ___________________________________________ _________________________________________ True / False 4. Jesus spoke extensively about his beliefs that homosexuality was wrong, and that people should be celibate outside of marriage. ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Religious Teaching on Relationships and Families Sex and the Church We are going to watch a BBC Two programme, Sex and the Church, where we will learn about how Jesus was considered a social radical in his time by insisting on monogamy and no divorce. Answers 1. Growing up in Galilee, Jesus was surrounded by Greek, Roman, and Jewish culture, so he would have been aware of the contradictory attitudes towards sex within the Middle East at the time. -

The Pornography Pandemic: Implications, Scope and Solutions for the Church in the Post-Internet Age

Southeastern University FireScholars Selected Honors Theses Spring 2018 THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE Dillon A. Diaz Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Diaz, Dillon A., "THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE" (2018). Selected Honors Theses. 127. https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors/127 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE by Dillon Amadeus Diaz Submitted to the Honors Program Committee in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors Scholars Southeastern University 2018 Diaz 1 Copyright by Dillon Amadeus Diaz 2018 Diaz 2 Dedication To Dr. Gordon Miller, whose Thesis class I accidentally missed on the 12th of March, 2018. I asked if I missed anything important; he replied, “Of course you missed something important. My class is always important.” To Dr. Joseph Davis, my thesis advisor and greatest inspiration in the defense of the true faith, whose words still ring true in my ears: “You either worship a God of revelation, or a God of imagination.” To Abigail Sprinkle, my beautiful bride-to-be, lovely beyond compare. One night, I told her every wicked thing I had ever done, and she looked at me with a smile that betrayed everything I had just confessed. -

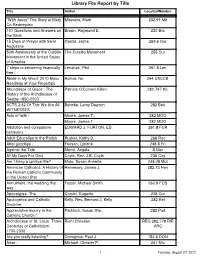

Library File Report by Title

Library File Report by Title Title Author LocalCallNumber "With Jesus" The Story of Mary Miravalle, Mark 232.91 Mir Co-Redemptrix 101 Questions and Answers on Brown, Raymond E. 220 Bro the Bible 15 Days of Prayer with Saint Garcia, Jaime 269.6 Gar Augustine 50th Anniversary of the Cursillo The Cursillo Movement 255 Cur Movement in the United States of America 7 steps to becoming financially Lenahan, Phil. 261.8 Len free : Abide in My Word: 2010 Mass Author, No 264 USCCB Readings at Your Fingertips Abundance of Grace : The Patricia O'Connell Killen 282.797 KIL History of the Archdiocese of Seattle 1850-2000 ACTS 2:32 Of This We Are All Behnke, Leroy Deacon 282 Beh WITNESSES Acts of faith : Moore, James T., 282 MOO Moore, James T., 282 MOO Addiction and compulsive EDWARD J. FURTON, ED. 261.8 FUR behaviors : Adult Education in the Parish Rucker, Kathy D. 268 Ruc After goodbye : Friesen, Lynette. 248.8 Fri Against the Tide Merici, Angela B Mer All My Days For God Coyle, Rev. J.B. Coyle 235 Coy Am I living a spiritual life? : Muto, Susan Annette. 248.48 Mut American Catholics: A History of Hennesey, James J. 282.73 Hen the Roman Catholic Community in the United Stat Annulment, the wedding that Foster, Michael Smith. 262.9 FOS was : Apocalypse, The Corsini, Eugenio 228 Cor Apologetics and Catholic Kelly, Rev. Bernard J. Kelly 282 Kel Doctrine Appreciative inquiry in the Paddock, Susan Star. 282 Pad Catholic Church / Archdiocese of St. Louis: Three Riehl,Christian REG 282.778 RIE Centuries of Catholicism, ARC 1700-2000 Are you really listening? : Donoghue, Paul J. -

Laura L. Garcia

Laura L. Garcia CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Philosophy Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02143 [email protected] (617) 251-4483 EDUCATION Ph.D. Philosophy, 1983, University of Notre Dame M.A. Philosophy, 1979, University of Notre Dame B.A. Philosophy, 1977, Westmont College, summa cum laude, honors in philosophy TEACHING EXPERIENCE Boston College Scholar in Residence 2011-Present Boston College Adjunct Assistant Professor 1999-2005 Rutgers, State University of New Jersey Part-Time Lecturer 1993-1999 Georgetown University Visiting Assistant Professor 1988-1992 The Catholic University of America Visiting Lecturer 1986-1987 The University of Notre Dame Adjunct Assistant Professor 1984-1986 University of St. Thomas (St. Paul, MN) Instructor 1982-1984 Calvin College Instructor 1979-1980 St. Mary’s College (South Bend, IN) Instructor Spring 1979 COURSES TAUGHT Philosophy of Religion History of Metaphysics Philosophy of Being and God Introduction to Philosophy Religion and the Challenge of Science Philosophy of the Person Metaphysics of God Critical Thinking and Informal Logic Does God Exist? Symbolic Logic Faith and Reason Introduction to Ethical Theory Religion and Morality Analytic Philosophy Miracles and Immortality Contemporary Metaphysics PUBLICATIONS Books Editor and Introduction, Truth, Life and Solidarity: The Impact of John Paul II on Philosophy (New York: Crossroads, 2010). Articles and Book Chapters “An Inference Model of Basic God Beliefs,” under consideration at a reviewed journal. “Equality and Freedom” in Erika Bachiochi, ed. Women, Sex and the Church: A Case for Catholic Teaching (Boston: Pauline Books, 2010). "Does Maritain Solve the Problem of Evil?" in James Hanink, ed. Maritain Conference Papers (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, forthcoming). -

View / Download 1.3 Mb

Copyright by Amanda L. Olson 2019 Abstract The Evangelical Covenant Church, like so many Christian denominations, is embroiled in conflict over homosexuality and gay marriage. This small North American denomination cannot afford a split, not only due to its small size, but because doing so would fundamentally deny its very identity. Thankfully, it is the denomination’s shared identity that gives the church, and sexual minorities, hope for the future. The ECC is a gathering of churches that covenant together for the sake of God’s mission in the world. It’s pietistic history and ethos values relational unity over doctrinal uniformity, making gracious space for theological diversity for the purpose of that mission. It’s affirmations and distinctives provide a strong DNA for the church to flourish in the midst of a rapidly changing culture. Homosexuality and gay marriage are complex problems in the church. They challenge fundamental beliefs, values and identities, and they are inherently personal and emotional topics. In order to address this challenge, church leaders must learn new ways of leading. This paper proposes that an adaptive leadership framework provides the tools necessary for the Evangelical Covenant Church to faithfully and fully take on the challenge without compromising its commitment to Christ and the authority of the Bible. It offers practical resources to assist local congregations in discussing the topic. And, it suggests ways that denominational leadership can support the work of the local congregation. For the children of Grace Evangelical Covenant Church, Chicago, especially Ben. That you may find the Covenant a place of vibrant faith. -

A Plea for Human Ecology: on the Prophetic Value of Humanae Vitae for Today

1 A Plea for Human Ecology: on the Prophetic Value of Humanae Vitae for today Michele M. Schumacher, S.T.D., habil. University of Fribourg, Switzerland “The only way to discuss the social evil is to get at once to the social ideal,” writes G. K. Chesterton in his insightful book, What’s Wrong with the World. “[A]nd the upshot of the title can be easily and clearly stated,” the famous English author continues. “What is wrong is that we do not ask what is right.”1 Missing in England in 1910—and the lack has arguably only aggravated throughout much of the western world in the interim—was, in other words, the notion of timeless anthropological, and thus also moral, norms governing the human species. In fact, today, as differing from Chesterton’s time,2 it is considered “normal” to accord to individual consciences “the prerogative of independently determining the criteria of good and evil and then acting accordingly,”3 Pope John Paul II observed some twenty years ago. “Indeed, when all is said and done man would not even have a nature; he would be his own personal life project. Man would be nothing more than his own freedom!”4 Such, more specifically—as I have extensively exposited elsewhere5—is what the saintly pope presented as “a freedom which is self-designing,”6 or “self-defining,” a “phenomenon creative of itself and its values,”7 an autonomous power “whose only reference point” is, as Ratzinger observed during the same period, what the individual conceives as “his own [subjective] good.”8 As differing from what the Belgian theologian Servais Pinckaers calls “freedom for excellence”—that is to say, freedom “rooted in the soul’s spontaneous inclinations to the true and the good”9—this fundamentally subjective conception of freedom is, Ratzinger continues, “no longer seen positively as a striving for the good, which reason uncovers with help from the community and tradition.” Instead, it is “defined […] as an emancipation from all conditions that prevent each one from following his own reason;”10 1 G. -

Paradox in Discourse on Sexual Pleasure: a Feminist

PARADOX IN DISCOURSE ON SEXUAL PLEASURE: A FEMINIST PASTORAL THEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION By Elizabeth R. Zagatta Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion December, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Bonnie Miller-McLemore Professor Ellen Armour Professor Volney Gay Professor Laura Carpenter Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth R. Zagatta All Rights Reserved ii To my parents, George and Rosanne, and my little sis, Rebecca, For their love and support in scholarship and in life. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am overwhelming grateful to many individuals for their love, support, input, and encouragement throughout the course of writing this dissertation. I want to begin by offering my thanks to the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities for the generous fellowship that funded my last year of writing. The Center also provided resources for moving forward with academic jobs in the academy and organized a writing group with other graduate fellows, whose feedback and input was invaluable to my work. A number of local organizations and individuals have supported me over the course of my time as a doctoral student, allowing for timely completion of the dissertation. Thank you to Amy Mears, April Baker, Thomas Conner, and the congregation of Glendale Baptist Church of Nashville, TN, to Chris O’Rear and the Pastoral Counseling Centers of Tennessee, to the Law Firm of Bart Durham, to Lynn Reed and the staff at JAS Forwarding, to Dr. Anita Hauenstein, and to the students and professors of the graduate psychology department at Trevecca Nazarene University.