A Case Study of Collaborative Practice: Working to Promote Cross- Curricular Thinking and Making Within Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

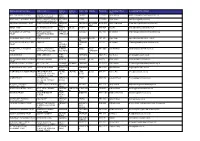

Pyramid School Name Pyramid School Name Airedale Academy the King's School Airedale Junior School Halfpenny Lane JI School Fairb

Wakefield District School Names Pyramid School Name Pyramid School Name Airedale Academy The King's School Airedale Junior School Halfpenny Lane JI School Fairburn View Primary School Orchard Head JI School Airedale King's Oyster Park Primary School St Giles CE Academy Townville Infant School Ackworth Howard CE (VC) JI School Airedale Infant School Larks Hill JI School Carleton Community High School De Lacy Academy Cherry Tree Academy Simpson's Lane Academy De Lacy Primary School St Botolph's CE Academy Knottingley Carleton Badsworth CE (VC) JI School England Lane Academy Carleton Park JI School The Vale Primary Academy The Rookeries Carleton JI School Willow Green Academy Darrington CE Primary School Minsthorpe Community College Castleford Academy Carlton JI School Castleford Park Junior Academy South Kirkby Academy Glasshoughton Infant Academy Common Road Infant School Minsthorpe Half Acres Primary Academy Upton Primary School Castleford Smawthorne Henry Moore Primary School Moorthorpe Primary School Three Lane Ends Academy Northfield Primary School Ackton Pastures Primary Academy Ash Grove JI School Wheldon Infant School The Freeston Academy Cathedral Academy Altofts Junior School Snapethorpe Primary School Normanton All Saints CE (VA) Infant School St Michael's CE Academy Normanton Junior Academy Normanton Cathedral Flanshaw JI School Lee Brigg Infant School Lawefield Primary School Martin Frobisher Infant School Methodist (VC) JI School Newlands Primary School The Mount JI School Normanton Common Primary Academy Wakefield City Academy -

Castleford Academy Ferrybridge Road, Castleford, West Yorkshire, WF10 4JQ

School report Castleford Academy Ferrybridge Road, Castleford, West Yorkshire, WF10 4JQ Inspection dates 25–26 September 2012 Previous inspection: Not previously inspected Overall effectiveness This inspection: Good 2 Achievement of pupils Good 2 Quality of teaching Good 2 Behaviour and safety of pupils Good 2 Leadership and management Good 2 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a good school. Students’ achievement is good. Most students In many lessons students are provided with throughout the academy made good progress imaginative, stimulating and challenging and their achievement in English is good. activities which meets their needs However students’ progress and attainment is appropriately. Working with their peers, weaker in mathematics. engaging in constructive debate secures Students are keen to learn and their students’ progress and develops their attendance is above average. They are understanding and skills within different tolerant of and show respect for each other subjects. and especially towards those students with a The Principal and members of the governing hearing impairment. body are ambitious and use performance The sixth form, although small, is good and management effectively to challenge staff the courses offered meet the needs of the and improve the quality of teaching. students. Teaching is good and this enables Challenging targets are set. Strong support students to reach their individual goals. and guidance are provided so they may be achieved. It is not yet an outstanding school because Students’ attainment and progress in There is insufficient outstanding teaching to mathematics is not at the same level as that promote high quality learning. In addition, in English. -

Careers Policy

Castleford Academy Careers Education, Information, Advice and Guidance (CEIAG) Policy Version No: Date Ratified: Review Date: 2.0 11.12.2019 11.12.2020 Contents 1. Mission Statement ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Vision ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Aims ................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 4. Objectives .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 5. Entitlement ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 6. Team .................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 7. Management of Information, Advice and Guidance ......................................................................................................... 4 8. Careers Education and Information, Advice and Guidance ............................................................................................. -

21 May 2021 Dear Parent/Carer I Would Like to Start with a Huge Thank

21 May 2021 Dear Parent/Carer I would like to start with a huge thank you to our fantastic staff who have continued to deliver high quality engaging lessons for our students during these challenging times. Student engagement continues to be of a high standard so a big thank you also to our students who have shown great determination to keep up with their studies. Our thanks also to our parents and carers for their support and encouragement in what has been another unprecedented year. After nearly four years in post as Principal of The Featherstone Academy, I share the news that I will be leaving my position in the summer to take on the role of Headteacher of Castleford Academy with effect from September. I am sad to see my role as Principal come to a close, especially under the current COVID school operations, where I am unable to announce this change to our students or staff in person. Exciting new challenges lie ahead for me however I will greatly miss The Featherstone Academy, its students, staff and community. I hold a deep respect and affection for the academy. It has been my honour and privilege to lead the academy during the past four years and I truly believe the academy will continue to make the progress we have made under the guidance of The Rodillian Multi Academy Trust. The Featherstone Academy is a wonderful community and I know it will continue to offer a high quality education and rich experience for its young people. It is a school to be proud of. -

HRBQ-2013-Area-Wakefield-South

Children and Young People’s Health and Well- being in the Wakefield South East Locality A Public Health summary report of the Health Related Behaviour Survey 2013 Wakefield District Public Health This report is based on the results to the combined sample team have been using the Health primary and secondary survey for schools in their age phase. Related Behaviour Survey every results from 406 Year 5 and Cross-phase data and analysis two years since 2009 as a way of Year 9 pupils living in the collecting robust information Wakefield South East Locality of Where possible, responses have about young people’s health and the Wakefield District. Separate been cross-analysed and lifestyles. This latest survey was reports are available for the presented to highlight undertaken in the spring term of other locality areas alongside the similarities and differences in 2013. District Wide and FE reports. behaviours between groups. Furthermore, some of the The content of the survey has Teachers were briefed on how to primary and secondary been widely consulted upon and collect the most reliable data by questions are identical or very tailored for Wakefield District’s Schools Health Education Unit similar allowing for comparison needs. Three separate versions staff. Surveys were completed across the age range. of the survey have been used anonymously either online or on with age appropriate questions paper. Each of the schools has its as standard. own report comparing their 3416 young people were involved in the survey: TOPICS INCLUDE: South East Wakefield Locality District Healthy Living School Year Year 5 Year 9 Year 5 Year 9 Total Diet, physical exercise, drugs, Age 9-10 13-14 9-10 13-14 alcohol, illness and sexual health Boys 85 120 531 1145 1676 Girls 59 142 499 1241 1740 Good Relationships and Mental Health Total 144 262 1030 2386 3416 Friends, worries, stress & depression This is one of a set of 7 Locality reports. -

Fourteentosixteen 2019/20

fourteentosixteen prospectus 2019/20 14-16 prospectus 2018/19 Welcome School Partnerships Team Contents Contact Dear Colleague, General Telephone: 01924 789789 Working with our partner schools ....................................4 Diploma in Motor Vehicle Studies ..................................25 At Wakefield College, our Course Information: 01924 789111 learners are at the heart of Our School Liaison offer ........................................................4 Certificate in Vehicle Systems Maintenance .............26 Minicom: 01924 789270 all we do and we recognise that everyone has different Technical Awards ...........................................................................5 Extended Certificate in Music Practitioners .............. 27 General Enquiries: [email protected] ambitions and needs. Course Information: [email protected] First Award in Animal Care ..................................................6 Diploma in Performing Arts ............................................. 28 We offer a fantastic choice Website: www.wakefield.ac.uk of courses for 14-16 year Award in Motor Studies ........................................................7 Certificate in Performing Engineering Operations .29 olds and some of the best All Wakefield College prospectuses are available training facilities in the in text format on the College website. James Pennington Sandra Lockett Award in Child Development and Care .........................8 Diploma in Public Services .................................................30 region, -

Castleford Academy Ferrybridge Road, Castleford, Wakefield, WF10 4JQ

School report Castleford Academy Ferrybridge Road, Castleford, Wakefield, WF10 4JQ Inspection dates 24–25 September 2014 Previous inspection: Good 2 Overall effectiveness This inspection: Good 2 Leadership and management Good 2 Behaviour and safety of pupils Good 2 Quality of teaching Good 2 Achievement of pupils Good 2 Sixth form provision Requires improvement 3 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a good school. The percentage of students who gain five good Bullying is extremely rare and students feel safe. passes at GCSE, including English and When bullying does occur, it is dealt with swiftly. mathematics, has risen steadily so that it is now Staff and parents are extremely positive about all above the national average. aspects of the academy and hold a strong sense of Progress across most subjects continues to rise support and belief in the academy and its staff. for most pupils, particularly for English and Leaders continue to seek opportunities to further mathematics, so that students do well compared raise standards of behaviour and the achievement to their peers nationally. students make across all subjects. They are swift to The support offered to students with special deal with underperformance of staff so that educational needs, particularly in the hearing- students receive a good education. impaired unit, is very strong so that those The pastoral care of students is excellent. There are students do as well as their peers. many opportunities for students to experience life Teaching is continuing to improve due to the beyond the academy and support for the spiritual, successful drive by governors and leaders to raise moral, social and cultural education is strong. -

HRBQ-2013-Focus-Further-Education

Young People's Health and Well- being in Wakefield District FE A summary report of the Health Related Behaviour Survey 2013 Wakefield District Public The content of the survey has staff. Surveys were completed Health team have been using been widely consulted upon either online or on paper. the Health Related Behaviour and tailored for Wakefield 2619 pupils from 8 Further Survey every two years since District’s needs. Three separate Education institutions took part. 2009 as a way of collecting versions of the survey have robust information about young been used with age appropriate Each institution has its own people’s health and lifestyles. questions as standard. report comparing their results to This is the second time FE the combined sample for This report focuses on the FE colleges in Wakefield District. colleges have participated, this version of the survey. Staff latest survey was undertaken in were briefed on how to collect The 2011 figures are shown in the spring term of 2013. the most reliable data by brackets ( ) throughout this Schools Health Education Unit report. 2619 young people were involved in the 2012/2013 survey: TOPICS INCLUDE: Study Year Year 1 Year 2/3 Total Healthy Living Age 16 - 17 17 - 19 Diet, physical exercise, drugs, alcohol, illness and sexual Males 984 355 1339 health Females 1001 279 1280 Good Relationships and Total 1985 634 2619 Mental Health Friends, worries, stress & depression Additional reports An overall Wakefield District report containing the combined results Being Safe from the main schools survey is available to accompany this FE report. The Wakefield schools data have also been sub-divided into Bullying, crime, accidents locality datasets. -

22 July 2021 Dear Parents/Carers As This

22 July 2021 Dear Parents/Carers As this academic year comes to a close, it is an honour to write to you to introduce myself as the new Principal of The Featherstone Academy from the beginning of the new school year. As you are aware, Mr Wesley Bush is moving to become the new Headteacher at Castleford Academy. Featherstone’s loss is Castleford’s gain. On behalf of the school and the community I would like to acknowledge the amazing work that he has done over the last four years in ensuring that students of Featherstone are launched into their next steps with the skills and qualifications that they require in order to achieve their aspirations. I am looking forward to continuing Featherstone’s progress and providing an excellent education for the young people of the community. At the end of every year we say goodbye to some staff as they move on with their careers. We thank all those who depart and have contributed so much to school life. Mr Miller is leaving the academy and is being replaced as Deputy Headteacher by Ms Roberts who joins us from Brayton Academy. There are two new members of staff in PE: Mrs Holdsworth and Mr Callum, and Mr Benton is leaving to work in one of our other academies. Miss Claringbold will be leaving to run a larger department at Brayton Academy and we welcome Mrs Champagnon to our French department. Mr Barker is retiring this year and Ms Beckett will be joining us in Geography along with Mr Evans who will be joining us to teach Music to KS3 students. -

Multi-Academy Trust Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line

Multi-academy trust name Address Line 1 Address Address Town / City County Postcode Accounting Officer Accounting Officer Email Line 2 Line 3 name ABBEY ACADEMIES TRUST BOURNE ABBEY C OF E ABBEY BOURNE PE10 9EP Sarah Moore [email protected] PRIMARY ACADEMY ROAD ABBEY MULTI ACADEMY TRUST ABBEY GRANGE CHURCH BUTCHER LEEDS LS16 5EA Carol Kitson [email protected] OF ENGLAND ACADEMY HILL ABINGDON LEARNING TRUST RUSH COMMON SCHOOL HENDRED ABINGDON OXFORDS OX14 2AW Laura Youngman [email protected] WAY HIRE ABNEY TRUST The Kingsway School Foxland Cheadle Cheshire SK8 4QX Jo Lowe [email protected] Road ACADEMIES ENTERPRISE KILNFIELD HOUSE STATION HOCKLEY SS5 4HS Ian Comfort [email protected] TRUST FOUNDRY BUSINESS APPROACH PARK ACADEMIES SOUTH WEST BALKWILL ROAD KINGSBRID DEVON TQ7 1PL Roger Pope [email protected] GE ACADEMY TRANSFORMATION ROOM 501 ONE BIRMINGH B1 1BD Ian Cleland [email protected] TRUST VICTORIA AM SQUARE ACCORD MULTI ACADEMY OSSETT ACADEMY & STORRS OSSETT WEST WF5 0DG Alan Warboys [email protected] TRUST SIXTH FORM COLLEGE HILL ROAD YORKSHIR E ACE LEARNING REED CRESCENT PARK ASHFORD TN23 3PA Paul Ketley [email protected] FARM ACE SCHOOLS MULTI ACADEMY Martinsgate Building Bretonside Plymouth Devon PL4 0AT Sarah Gillett [email protected] TRUST ACORN ACADEMY CORNWALL Unit 4 East Pool Tolvaddon Tolvaddon Camborne TR14 0HX Rob Gasson [email protected] Energy Park ACORN -

December 2020 FOI 6051-20 Police Officers in Schools

Our ref: 6051/20 In relation to the discloure link https://www.westyorkshire.police.uk/sites/default/files/foi/2020-07/july_2020_foi_1715- 20_officers_in_schools.pdf Could I please just check one point: Could you specify the names of schools to which 43.65 officers were deployed in 2019-20? Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police have maintained engagement with schools through the Safer Schools Partnership, a national way of working to foster intensive and long-term engagement with the school community whether pupils, teachers, governors or parents. The partnership has seen members of the Force, usually police officers, but in some cases PCSOs, fulfil their operational duties in a school-based environment as a resident member of staff. The partnership has involved schools contributing a certain percentage of an officer’s/PCSOs salary in return for their work in the school. The precise percentage has varied from school to school. It also determines the percentage of time they spend at the school, so a 20% contribution may mean that an officer spends 1 day a week at the school. Leeds Bradford Wakefield Kirklees Coop Appleton Academy Kings School, Pontefract Hudd Uni Brigshaw Beckfoot School South Kirby Academy Kirklees College Beckfoot Upper Heaton (was Belle Vue Upton Primary All Saints Catholic Garforth/Delta Academies Boys) (Minsthorpe Feeder) College Corpus Christi Belle View Girls School Outwood Grange Pivot Outwood Academy Mount St Marys Bradford Academy Spen Valley Hemsworth Temple Moor High School Red Kite Whitcliffe -

Local-Agreed-Syllabus-For-Religious

Wakefield SACRE RE Agreed Syllabus 2013-18 Wakefield RE Syllabus 2013 Designed by Chelsea Javidi-Barazandeh from Cathedral Academy Wakefield 1 Wakefield SACRE RE Agreed Syllabus 2013-18 SACRE Membership Keith Worrall Support officer to SACRE, Wakefield LA Pete Forster Support officer to SACRE, Wakefield LA (2013) Lyndsay Mason Headteacher, Darrington CE Primary School Jill Davidson Teacher of RE, Horbury School Nadeem Ahmed Councillor Roz Lund Councillor David Hopkins Councillor Olivia Rowley Councillor Jane Gosney Church of England John Wadsworth Free Church Federal Council John Smith Observer Jill Davidson Teacher, Horbury Academy Maria Stead Teacher, Cathedral Academy Mark Taylor NAHT (The Association of all School Leaders) Maureen Mitchell ATL (Association of Teachers and Lecturers) Elizabeth Martin Free Church Federal Council Nicola Madarasz Teacher, Minsthorpe Community College Rev Alan Loosemore Free Church Federal Council Rev Gill Johnson Church of England The Reverend Canon Ian Wildey Diocese of Wakefield Sue Millar Clerk to SACRE 2 Wakefield SACRE RE Agreed Syllabus 2013-18 The Agreed Syllabus for RE in Wakefield, 2013 Contents Foreword and Pupil Voice 3 Statutory guidance summary 5 Why RE matters 6 The purposes and aims of RE 7 Learning about religion and belief + learning from religion and belief: 8 2 attainment targets The benefits of RE for each learner: five significant areas 9 Curriculum Time for RE 10 RE Learning and the whole curriculum 12 . RE and community cohesion . Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural development and RE . Key skills in RE . Promoting other aspects of learning through RE . RE and the general teaching requirements: inclusion . Attitudes, skills and processes for learning in RE Programmes of study: 20 .