Sharon Francis Interview II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Career Overview 2019

ELAINE PAIGE A CAREER OVERVIEW 2019 Official Website: www.elainepaige.com Twitter: @elaine_paige THEATRE: Date Production Role Theatre 1968–1970 Hair Member of the Tribe Shaftesbury Theatre (London) 1973–1974 Grease Sandy New London Theatre (London) 1974–1975 Billy Rita Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (London) 1976–1977 The Boyfriend Maisie Haymarket Theatre (Leicester) 1978–1980 Evita Eva Perón Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1981–1982 Cats Grizabella New London Theatre (London) 1983–1984 Abbacadabra Miss Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith Williams/Carabosse (London) 1986–1987 Chess Florence Vassy Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1989–1990 Anything Goes Reno Sweeney Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1993–1994 Piaf Édith Piaf Piccadilly Theatre (London) 1994, 1995- Sunset Boulevard Norma Desmond Adelphi Theatre (London) & then 1996, 1996– Minskoff Theatre (New York) 19981997 The Misanthrope Célimène Peter Hall Company, Piccadilly Theatre (London) 2000–2001 The King And I Anna Leonowens London Palladium (London) 2003 Where There's A Will Angèle Yvonne Arnaud Theatre (Guildford) & then the Theatre Royal 2004 Sweeney Todd – The Demon Mrs Lovett New York City Opera (New York)(Brighton) Barber Of Fleet Street 2007 The Drowsy Chaperone The Drowsy Novello Theatre (London) Chaperone/Beatrice 2011-12 Follies Carlotta CampionStockwell Kennedy Centre (Washington DC) Marquis Theatre, (New York) 2017-18 Dick Whttington Queen Rat LondoAhmansen Theatre (Los Angeles)n Palladium Theatre OTHER EARLY THEATRE ROLES: The Roar Of The Greasepaint - The Smell Of The Crowd (UK Tour) -

Lesson Plan Part 1

Protest and Pride: The Entertainment Industry Response to the Vietnam War Rick Jackson Discovery Alternative High School Summer 2012 Call Number: LC-U9- 18528, frame 26 [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University The Vietnam War was a controversial and divisive conflict in American history. Even today, decades later, we debate whether or not American soldiers should have been a part of the conflict. The response of the public on both sides was vocal and sometimes violent. Students will explore the American public’s response to the Vietnam War through the prism of members of the entertainment industry. In groups, they will examine primary sources from both side of the controversy. Overview/ Materials/Historical Background/LOC Resources/Standards/ Procedures/Evaluation/Rubric/Handouts/Extension Overview Back to Navigation Bar Objectives Students will: gain a sense of the divisiveness of the Vietnam war explore the varying positions within the reaction to the war critically think about primary sources and what they can tell us constructively share their own understandings learn and practice teamwork skills Recommended time frame Three 55 minute class periods Grade level High School Curriculum fit US History – Vietnam War Materials Internet access Data projector Print copies of: Eartha Kitt photos, John Wayne letter, Bob Hope photo, Bob Hope letter, Jane Fonda Photo, Haymarket Square letter Primary source analysis handouts for Advertisements, Photos, and Letters 4 medium flip charts Access to word processing Michigan State Learning Standards Back to Navigation Bar 8.2 Domestic Policies Examine, analyze, and explain demographic changes, domestic policies, conflict, and tensions in Post-WWII America. -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Eden Ahbez TITLE Wild Boy The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BAF 18018 PRICE-CODE BAF EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy180187z FORMAT VINYL-album with gatefold sleeve • 180g vinyl GENRE Rock 'n' Roll / Tiki TRACKS 14 PLAYING TIME 37:26 G Hippie #1 G 14 rare/unreleased recordings G Guest appearances by Paul Horn, Eartha Kitt, and more G 180 gram vinyl G Fully annotated, with never before seen pictures INFORMATION By now psychedelic music is a mainstay of popular taste. But questions of its origins still linger. As such, BEAR FAMILY RECORDS now submits 'Wild Boy: The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez' as fresh evidence in the quest for answers. Over the past twenty years Ahbez has gone from cult figure to harbinger of the Sixties flower-power movement. This notion is born out largely by his 1948 ant- hem of universal love, Nature Boy, and his rare solo album from 1960, titled 'Eden's Island' – one of popular music's earliest con- cept albums. 'Wild Boy: The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez' both expands the Ahbez catalog and deepens the notion of a psychedelic movement having roots in the 1950s. Side one acts as a compilation of music that Ahbez wrote in the aftermath of Nature Boy. Inclusion of songs like Palm Springs by the Ray Anthony Orchestra and Hey Jacque by Eartha Kitt give listeners the chance to hear obscure cuts by big-name artists in the context of Ahbez for the first time. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Eartha Kitt

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Eartha Kitt PERSON Kitt, Eartha Alternative Names: Eartha Kitt; Life Dates: January 17, 1927-December 25, 2008 Place of Birth: North, South Carolina, USA Work: Scarsdale, New York Occupations: Actress; Singer Biographical Note Eartha Kitt was an international star who gave new meaning to the word versatile. She distinguished herself in film, theater, cabaret, music, and on television. Kitt was one of only a handful of performers to be nominated for a Tony (three times), a Grammy (twice), and an Emmy Award (twice). She enthralled New York nightclub audiences during her extended stays at the Café Carlyle. These intimate performances have been captured in, Eartha Kitt, Live at The Carlyle. at The Carlyle. Eartha Mae Kitt was born on January 17, 1927. She was ostracized at an early age because of her mixed- race heritage. At eight years old, Kitt was given away by her mother and sent from the South Carolina cotton fields to live with an aunt in Harlem. In New York, her distinct individuality and flair for show business manifested itself, and on a friend's dare, the shy teen auditioned for the famed Katherine Dunham Dance Troupe. She won a spot as a featured dancer and vocalist, and before the age of twenty, toured worldwide with the company. During a performance in Paris, Kitt was spotted by a nightclub owner and booked as a featured singer at his club. Her unique persona earned her fans and fame quickly, including Orson Welles. Welles was so taken with her talent that he cast her as “Helen of Troy” in his fabled production of Dr. -

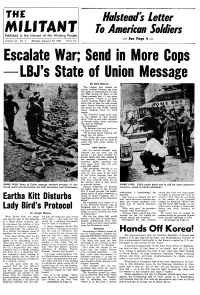

Send in More Cops LBJ's State of Union Message

UntalftHINIIIHIItHIIIIUtiiHitiiUIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIlllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllnllltlllllllfHHINftiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIIIIHIItllllllllllllllltllllllllllllllfiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIUtllfllllllllllllllllttulllllltllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll. THE Holsteotl's Letter MILITANT To Amerimn Soldiers Published in the Interest of the Working People -See Page 4- Volume 32 -No. 5 Monday, January 29, 1968 Price lOc llllllllllllllllllllllllfllllllllllll1iH11tlllllllllllltlllllllllllltlln.tiiiiiii11111111111111111111111U111111111111111111111111111111111111liiiUIIUIIUIIIIII!IUHUIIHII!IIIIIIIHHIIIII!Itlii!HIIIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIIIIIUIIIIII!l!iUIIHHII11!11111111111111111111111111111111111111UI Escalate War; Send in More Cops LBJ's State of Union Message By Dick Roberts The longest and loudest ap plause Lyndon Johnson got from the gang of reactionaries on Cap itol Hill during his State of the Union message Jan. 17 was when he declared: "There is no more urgent business before this Con gress than to pass the safe streets acts." Every cheering racist pres ent knew he was really talking about cracking down on black people. The President spent more time on the subject of "law enforce ment" than on any other domestic or foreign policy issue, including the war in Vietnam. He promised: "To develop state and local mas ter plans to combat crime. "To provide better training and better pay for police. "To bring the most advanced technology to the war on crime in every city and every county in America." Only Answer For the second straight year, Johnson did not even pay lip service to the black struggle for human rights. His only answer to the demands expressed in last summer's ghetto uprisings was more guns, more cops, and even more FBI agents. One paragraph devoted to re· inforcing the FBI by 100 men took up more space in the State of the Union message than the plight of the nation's farmers, who have recently been hit by the sharpest drop in farm prices MORE WAR. -

Belknap Collection for the Performing Arts - the AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA COLLECTION

AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA CINEMA AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA The history of the African-American Cinema is a harsh timeline of racism, repression and struggle contrasted with film scenes of boundless joy, hope and artistic spirit. Until recently, the study of the "separate cinema" (a phrase used by historians John Kisch and Edward Mapp to describe the segregation of the mainstream, Hollywood film community) was limited, if not totally ignored, by writers and researchers. The uphill battle by black filmmakers and performers, to achieve acceptance and respect, was an ugly blot on the pages of film history. Upon winning his Best Actor Oscar for LILLIES OF THE FIELD (1963), Sidney Poitier accepted, on behalf of the countless unsung African-American artists, by acknowledging the "long journey to this moment." This emotional, heartbreaking and inspiring journey is vividly illustrated by the latest acquisition to the Belknap Collection for the Performing Arts - THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA COLLECTION. The valuable research material, housed in this collection, includes over 300 pressbooks (illustrated campaign and advertising catalogs sent to theatre owners), press kits (media packages including biographies, promotional essays and illustrations), programs and over 1000 photographs and slides. The journey begins with the blatant racism of D.W. Griffith's THE BIRTH OF A NATION (1915), a film respected as an epic milestone, but reviled as the blueprint for black film stereotypes that would appear throughout the 20th century. Researchers will follow African-American films through an extended period of stereotypical casting (SONG OF THE SOUTH, 1946) and will be dazzled by the glorious "All-Negro" musicals such as STORMY WEATHER (1943), ST.LOUIS BLUES (1958) and PORGY AND BESS (1959). -

IN PERSON & PREVIEWS Talent Q&As and Rare Appearances

IN PERSON & PREVIEWS Talent Q&As and rare appearances, plus a chance for you to catch the latest film and TV before anyone else TV Preview: World on Fire + Q&A with writer Peter Bowker plus cast TBA BBC-Mammoth Screen 2019. Lead dir Adam Smith. With Helen Hunt, Sean Bean, Lesley Manville, Jonah Hauer- King. Ep1 c.60min World on Fire is an adrenaline-fuelled, emotionally gripping and resonant drama, written by the award-winning Peter Bowker (The A Word, Marvellous). It charts the first year of World War Two, told through the intertwining fates of ordinary people from Britain, Poland, France, Germany and the United States as they grapple with the effect of the war on their everyday lives. Join us for a Q&A and preview of this new landmark series boasting a stellar cast, headed up by Helen Hunt and Sean Bean. TUE 3 SEP 18:15 NFT1 TV Preview: Temple + Q&A with writer Mark O’Rowe, exec producer Liza Marshall, actor Mark Strong, and further cast TBA Sky-Hera Pictures 2019. Dirs Luke Snellin, Shariff Korver, Lisa Siwe. With Mark Strong, Carice van Houten, Daniel Mays, Tobi King Bakare. Eps 1 and 2, 80min Temple tells the story of Daniel Milton (Strong), a talented surgeon whose world is turned upside down when his wife contracts a terminal illness. Yet Daniel refuses to accept the cards he’s been dealt. He partners with the obsessive, yet surprisingly resourceful, misfit Lee (Mays) to start a literal ‘underground’ clinic in the vast network of tunnels beneath Temple tube station in London. -

Foxtel-A-Z-Movies-October-2019.Pdf

OCTOBER 2019 A-Z MOVIES 2 DAYS IN NEW YORK facility and put infected civilians into COMEDY MOVIES 1995 Comedy (PG) antics in the lead up to the big day. ROMANCE MOVIES 2012 Comedy a permanent state of zombie rage. October 7, 11, 21, 25 ALFIE ARMY OF DARKNESS (MA 15+ sl) Jim Carrey, Ian McNeice. ROMANCE MOVIES 2004 THE AMERICAN PRESIDENT MOVIE GREATS 1992 Horror (M lv) October 11, 18, 26 28 WEEKS LATER Retired pet detective Ace Ventura Romance (M ls) ROMANCE MOVIES 1995 October 2, 12, 22, 29 Julie Delpy, Chris Rock. THRILLER MOVIES 2007 Horror is persuaded to travel to Africa and October 6, 11, 16, 22, 28 Romance (M l) Bruce Campbell, Embeth Davidtz. A French woman living in New York (MA 15+ hv) investigate the case of a missing and Jude Law, Marisa Tomei. October 5, 10, 14, 21, 28 Demonic forces time warp a man with her boyfriend has her life shaken October 26 endangered white bat. A charming womaniser is forced to Michael Douglas, Annette Bening. and his car into England’s Dark Ages, by a visit from her eccentric dad, Jeremy Renner, Rose Byrne. take stock of his shallow life when he When the widowed US president where he finds romance and faces off her sex-mad sister and an explosive The US Army helps repatriate ACE VENTURA JR: loses his one true love. begins dating a Washington lobbyist, against legions of undead beasts. ex-boyfriend. Mainland Britain, but one of the Pet DETECTIVE wild rumours decimate his approval returning refugees carries a terrible FAMILY MOVIES 2009 Comedy (PG) ALICE IN WONDERLAND ratings. -

Follies Collection of Anthony J

Follies Collection of Anthony J. Mazzaschi Inventory Updated February 28, 2017 Frame Description Year Company/Theatre City State Country Notes Number Display Script of 2011 Kennedy Center Washington DC USA Signed by entire cast. Box Bernadette Peters Purchased from Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS via E-Bay auction. Display Conductor’s Score 1971 Original Production New York NY USA Custom Bound; gift of Box Mathilda Pincus, copyist, to Thomas Z. Shepherd, producer; inscribed with a personal note from Pincus to Shepherd 1 Program 1998 Signature Theatre Arlington VA USA 2 Flyer 1987 Shaftesbury Theatre London UK 3 Album 1971 Original Cast New York NY USA 4 Program 2007 Key West Pops Key West FL USA Also one page cast insert 5 Poster 2009 Arlington Players Arlington VA USA Printed from a PDF 5 Program 2009 Arlington Players Arlington VA USA 6 Magazine 2001 Sondheim Review Chicago IL USA Spring issue 7 Book Dust Jacket 2003 Everything Was USA By Ted Chapin, published by Possible Knopf 8 Poster 2007 Encores! New York NY USA Standard version 9 Poster 1971 Original Production New York NY USA Original. Some damage. 10 Poster 2004 California Irvine CA USA Autographed by cast Conservatory of the Arts 11 Album 1987 Original London London UK Silver version, Shaftesbury Cast cast 1 Frame Description Year Company/Theatre City State Country Notes Number 12 Album 1985 Lincoln Center New York NY USA Autographed by Sondheim, Concert Cook, and Stritch 13 Invitation 1987 First night party at London UK Numbered (but not visible) Tony’s 13 Invitation 1987 First night party at London UK Numbered (but not visible) Tony’s Book Invitation 1987 First night party at London UK Tony’s 14 Brochure 1987 Shaftesbury Theatre London UK Framed with front and back covers visible 15 Program 1987 Shaftesbury Theatre London UK White curtain (preview) version- Marked “18-7-87” – three days before official opening. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Andrea Nyquist, Marketing & Engagement Manager PHONE: (O)203-574-4283, (M)719-640-2966 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.waterburysymphony.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, May 5, 2021 Waterbury Symphony Orchestra celebrates Duke Ellington and George Gershwin with Rhapsody in June WATERBURY, CT – Waterbury Symphony Orchestra presents Rhapsody in June, Saturday, June 12, 2021 at 4:00 p.m. at the Waterbury Arts Magnet School Courtyard, and Sunday, June 13, 2021 at 4:00 p.m. on the lawn at Five Points Center for the Visual Arts in Torrington. The weekend long celebration is a salute to two masters of swing, Duke Ellington and George Gershwin. The concert will feature some of Ellington’s most loved works including : It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing) and Jubilee Stomp and, of course, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue will be a centerpiece of the concert. This program underscores the WSO’s long history in the Waterbury community. On March 26, 1963, Duke Ellington was the piano soloist with the Waterbury Symphony Orchestra in a performance of New World A-Comin’, a landmark jazz score composed by Ellington. “I’m very excited about our salute to the music of Ellington and Gershwin. This concert is at the heart of the WSO’s history and mission, to use music as a bridge to connect audiences from different generations and diverse communities. We believe it is an opportunity to foster shared musical experiences and build community. It is the first in whatwe hope will be an ongoing series celebrating jazz, Latin music, and the rich legacy of the Great American Songbook,” says WSO Music Director & Conductor Leif Bjaland. -

Em Santa Baby Cover Press Release.Docx

PRESS RELEASE Contact: Emily (Em) Website: https://www.emmusic.net/ Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/em4yoursoul/ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Christmas Vibes-Em Releases New Cover ‘Santa Baby’ [City, State, December 15, 2020] --- The most-awaited annual festival Christmas is coming ever nearer and the undisputed best part of this holiday season besides the loved ones, family, friends, gifts, and tons of other pie is the music. To celebrate the happiness of this event with her fans renowned song-writer and singer Em has released her new single ‘Santa Baby’. Starting from instruments Em welcomes Christmas and Santa in her soulful, charming, fresh, and shining sharp voice. This song is originally performed by American singer Eartha Kitt and written by Joan Javits and Philip Springer. While talking about her music and the cover song ‘Santa Baby’, Em says; “I feel this song is a universal message and represents everyone’s wishes associated with Christmas. Through my music, I hope to answer what people’s spirits have been yearning for… peace, clarity, awareness, love. Joy, freedom, prayers, and strength. Santa Baby is very close to my heart as its lyrics are what my heart prays for and I hope everyone will like this cover in my voice”. New Jersey-born Em (short for Emily) is chiseling out musical and visual performance art that speaks from her heart and spirit. She believes in truth, peace, and humanity. Em has gained lots of success as a performer and worked with several renowned producers and musicians to produce excellent music. ‘Dear Life’, ‘Even When It Hurts’, ‘Blue Light’, and ‘Say What You Mean’ tracks have gained great love and appreciation from music lovers and Em expects the same love from her fans for ‘Santa Baby’ cover Em’s ‘Santa Baby’ is a lyrical video produced by Editions L.A. -

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION Paying Grateful Tribute to the Distinguished and Remarkable Life of Eartha Kitt, Noted Singer, Entertainer and Anti-War Activist

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION paying grateful tribute to the distinguished and remarkable life of Eartha Kitt, noted singer, entertainer and anti-war activist WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to honor the memory of cherished citizens of the State of New York who distinguished themselves in their profession and whose talent, charm, intellect and unique personality permeated all they did; and WHEREAS, It is with great sorrow and deep regret that this Legislative Body records the passing of Eartha Kitt on Thursday, December 25, 2008, at the age of 81; and WHEREAS, Born on January 17, 1927, in South Carolina, as Eartha Mae Keith, she danced, sang, and acted her way into the hearts of millions; and WHEREAS, For generations, the name Eartha Kitt was synonymous with sexy, sultry, and outspoken; since the tender age of 14, she worked the stage, and for nearly seven decades, she left her indelible imprint by her work on the big screen, television and recordings; and WHEREAS, Eartha Kitt's career-long persona, that of the seen-it-all sybarite, was set when she performed in Paris cabarets in her early 20s, singing songs that became her signatures, like "C'est Si Bon" and "Love for Sale"; and WHEREAS, Ms. Kitt, who began performing in the late 1940s as a dancer in New York, went on to achieve success and acclaim in a variety of mediums long before other entertainment multi-taskers like Julie Andrews, Barbra Streisand and Bette Midler; and WHEREAS, An international star who gave new meaning to the word versa- tile, she was one of only a handful of performers to be nominated for a Tony three times; and both a Grammy and an Emmy Award two times; she regularly enthralled New York nightclub audiences during her extended stays at The Cafe Carlyle; and WHEREAS, Those who want to see her as a seductive chanteuse should watch the 1958 film "St.