Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

The Founder Effect

Baen Books Teacher Guide: The Founder Effect Contents: o recommended reading levels o initial information about the anthology o short stories grouped by themes o guides to each short story including the following: o author’s biography as taken from the book itself o selected vocabulary words o content warnings (if any) o short summary o selected short assessment questions o suggested discussion questions and activities Recommended reading level: The Founder Effect is most appropriate for an adult audience; classroom use is recommended at a level no lower than late high school. Background: Published in 2020 by Baen Books, The Founder Effect tackles the lens of history on its subjects—both in their own words and in those of history. Each story in the anthology tells a different part of the same world’s history, from the colonization project to its settlement to its tragic losses. The prologue provides a key to the whole book, serving as an introduction to the fictitious encyclopedia and textbook entries which accompany each short story. Editors’ biographies: Robert E. Hampson, Ph.D., turns science fiction into science in his day job, and puts the science into science fiction in his spare time. Dr. Hampson is a Professor of Physiology / Pharmacology and Neurology with over thirty-five years’ experience in animal neuroscience and human neurology. His professional work includes more than one hundred peer-reviewed research articles ranging from the pharmacology of memory to the first report of a “neural prosthetic” to restore human memory using the brain’s own neural codes. He consults with authors to put the “hard” science in “Hard SF” and has written both fiction and nonfiction for Baen Books. -

The Ridicule of Time: Science Fiction, Bioethics, and the Posthuman

The Ridicule of Time: Science Fiction, Bioethics, and the Posthuman Jay Clayton American Literary History, Volume 25, Number 2, Summer 2013, pp. 317-340 (Article) Published by Oxford University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/alh/summary/v025/25.2.clayton.html Access provided by Vanderbilt University Library (6 Jun 2013 09:56 GMT) The Ridicule of Time: Science Fiction, Bioethics, and the Posthuman Jay Clayton* Suppose you were a science fiction fan, a Trekkie, and a transhumanist; you once paid to attend a seminar with Rae¨l, knew all about Extropy back in the day, and subscribed to Longevity Meme Newsletter; you have read articles about an “immortality gene” and were thrilled to see Science publish a genome-wide association study in 2010 identifying 150 genes that might improve your chances of living to 100; and you practice extreme caloric restriction while spending a fortune on dietary supple- ments. Over the years, you have zealously collected the following quotes but have forgotten the sources. Which of them do you think came from classic 1950s works of science fiction and which from publications by distinguished scientists, doctors, philosophers, and law professors? 1. We, or our descendents, will cease to be human in the sense in which we now understand that idea. (3) 2. By the standards of evolution, it will be cataclysmic— instantaneous. It has already begun. (181) 3. The new immortals, in the decisive sense, would not be like us at all. (265) 4. Man will go into history along with the Java ape man, the Neanderthal beast man, and the Cro-Magnon Primitive. -

Ted Nelson History of Computing

History of Computing Douglas R. Dechow Daniele C. Struppa Editors Intertwingled The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson History of Computing Founding Editor Martin Campbell-Kelly, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK Series Editor Gerard Alberts, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Advisory Board Jack Copeland, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Ulf Hashagen, Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany John V. Tucker, Swansea University, Swansea, UK Jeffrey R. Yost, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA The History of Computing series publishes high-quality books which address the history of computing, with an emphasis on the ‘externalist’ view of this history, more accessible to a wider audience. The series examines content and history from four main quadrants: the history of relevant technologies, the history of the core science, the history of relevant business and economic developments, and the history of computing as it pertains to social history and societal developments. Titles can span a variety of product types, including but not exclusively, themed volumes, biographies, ‘profi le’ books (with brief biographies of a number of key people), expansions of workshop proceedings, general readers, scholarly expositions, titles used as ancillary textbooks, revivals and new editions of previous worthy titles. These books will appeal, varyingly, to academics and students in computer science, history, mathematics, business and technology studies. Some titles will also directly appeal to professionals and practitioners -

Writing to Think

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Newport Papers Special Collections 2-2014 Writing to Think Robert C. Rubel Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers Recommended Citation Rubel, Robert C., "Writing to Think" (2014). Newport Papers. 41. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newport Papers by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 41 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Writing to Think The Intellectual Journey of a Naval Career NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 41 Robert C. Rubel Cover This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Writing to Think The Intellectual Journey of a Naval Career Robert C. Rubel NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS Newport, Rhode Island meyers$:___WIPfrom C 032812:_Newport Papers:_NP_41 Rubel:_InDesign:000 NP_41 Rubel-FrontMatter.indd January 31, 2014 10:06 AM Naval War College The Newport Papers are extended research projects that Newport, Rhode Island the Director, the Dean of Naval Warfare Studies, and the Center for Naval Warfare Studies President of the Naval War College consider of particular Newport Paper Forty-One interest to policy makers, scholars, and analysts. -

Ansible® 405 April 2021 from David Langford , 94 London Road, Reading, Berks, RG1 5AU, UK

Ansible® 405 April 2021 From David Langford , 94 London Road, Reading, Berks, RG1 5AU, UK. Website news.ansible.uk. ISSN 0265-9816 (print); 1740- 942X (e). Logo: Dan Steffan . Cartoon (‘Dragon’s Eye’): Ulrika O’Brien . Available for SAE, ticholama, hesso-penthol or resilian. MOVING ON. October 2021 will see the tenth anniversary of the online £50 reg; under-17s £12; under-13s free. See novacon.org.uk. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction , hosted by Orion and linked to the SOLD OUT . 21-24 Apr 2022 ! Camp SFW, Vauxhall Holiday Park, Gollancz SF Gateway ebook operation. Orion/Gollancz have now decided Great Yarmouth. See www.scifiweekender.com. All places presumably not to renew the contract on 1 October. The principal Encyclopedia taken by membership transfers from the cancelled March 2021 event. editors John Clute and David Langford plan to move sf-encyclopedia.com POSTPONED AGAIN . 27-29 May 2022 ! Satellite 7, Crowne Plaza, to their own web server and continue as seamlessly as possible with Glasgow. £70 reg (£80 at the door); under-25s £60; under-18s £20; much the same ‘look and feel’, perhaps with a new sponsor and certainly under-12s £5; under-5s £2. See seven.satellitex.org.uk. Former dates 21- with a few improvements that the current platform doesn’t allow. 23 May 2021. All existing memberships transferred to 2022; no refunds. Rumblings. DisCon III (Worldcon 2021, Washington DC), with one The Army of Unalterable Law of its two hotels not only closed but filing for bankruptcy, is unable to tell Peter S. Beagle and his current business partners regained rights ‘to members whether it will be a physical as well as a virtual convention. -

Forte JA T 2010.Pdf (404.2Kb)

“We Werenʼt Kidding” • Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 By Joseph A. Forte Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Robert P. Stephens (chair) Marian B. Mollin Amy Nelson Matthew H. Wisnioski May 03, 2010 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Astounding Science-Fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr., sci-fi, science fiction, pulp magazines, culture, ideology, Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, American exceptionalism, capitalism, 1939 Worldʼs Fair, Cold War © 2010 Joseph A. Forte “We Werenʼt Kidding” Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 Joseph A. Forte ABSTRACT In 1971, Isaac Asimov observed in humanity, “a science-important society.” For this he credited the man who had been his editor in the 1940s during the period known as the “golden age” of American science fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell was editor of Astounding Science-Fiction, the magazine that launched both Asimovʼs career and the golden age, from 1938 until his death in 1971. Campbell and his authors set the foundation for the modern sci-fi, cementing genre distinction by the application of plausible technological speculation. Campbell assumed the “science-important society” that Asimov found thirty years later, attributing sci-fi ascendance during the golden age a particular compatibility with that cultural context. On another level, sci-fiʼs compatibility with “science-important” tendencies during the first half of the twentieth-century betrayed a deeper agreement with the social structures that fueled those tendencies and reflected an explication of modernity on capitalist terms. -

Interstellar Travel and the Fermi Paradox

Interstellar Travel If aliens haven’t visited us, could we go to them? In this lecture we will have some fun speculating about future interstellar travel by humans. Please keep in mind that, as we discussed earlier, this cannot be considered a solution for the problems that we have on Earth, for the simple reason that the expense per person is utterly prohibitive and will remain so in any conceivable future scenario. Nonetheless, given enough time it could be that we have the capacity to move out into the galaxy. Incidentally, we will leave discussions of really far-out concepts such as wormholes to a future class. Interstellar distances The major barrier to interstellar travel is the staggering distance between stars. The closest one to the Sun is Proxima Centauri, which is 4.3 light years away but not a likely host to planets. There are, however, a few possibilities within roughly 10 light years, so that is a good target. How far is 10 light years? By definition it is how far light travels in 10 years, but let’s put this into a more familiar context. A moderately brisk walking pace is 5 km/hr, and since one light year is about 10 trillion kilometers, you would need about 20 trillion hours, or about 2.3 billion years, to walk that distance. The fastest cars sold commercially go about 400 km/hr, so you would need about three billion hours or a bit less than thirty million years. The speed of the Earth in its orbit, which is comparable to the speed of the fastest spacecraft we have constructed (all unmanned, of course), is about 30 km/s and even at that rate it would take about a hundred thousand years to travel ten light years. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

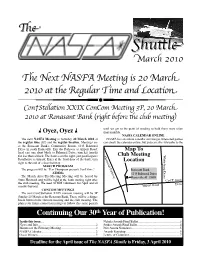

March 2010 the Next NASFA Meeting Is 20 March 2010 at the Regular Time and Location

Te Shutle March 2010 The Next NASFA Meeting is 20 March 2010 at the Regular Time and Location Con†Stellation XXIX ConCom Meeting 3P, 20 March 2010 at Renasant Bank (right before the club meeting) until we get to the point of needing to hold them more often d Oyez, Oyez d than monthly. NASFA CALENDAR ONLINE The next NASFA Meeting is Saturday 20 March 2010 at NASFA has an online calendar on Google. Interested parties the regular time (6P) and the regular location. Meetings are can check the calendar online, but you can also subscribe to the at the Renasant Bank’s Community Room, 4245 Balmoral Drive in south Huntsville. Exit the Parkway at Airport Road; Map To head east one short block to Balmoral Drive; turn left (north) Whitesbur for less than a block. The bank is on the right, just past Logan’s Memorial Parkway Club Meeting Roadhouse restaurant. Enter at the front door of the bank; turn Location right to the end of a short hallway. MARCH PROGRAM The program will be “Dan Thompson presents Fan Films.” Renasant Bank g Drive ATMMs 4245 Balmoral Drive The March After-The-Meeting Meeting will be hosted by Huntsville AL 35801 Sunn Hayward and will be held at the bank starting right after Carl T. Jones the club meeting. We need ATMM volunteers for April and all Drive months beyond. Airport Road CONCOM MEETINGS The next Con†Stellation XXIX concom meeting will be 3P Sunday 20 March at the Renasant Bank. There will be a dinner break between the concom meeting and the club meeting.