Irish Language (Historical Linguistic Overview)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

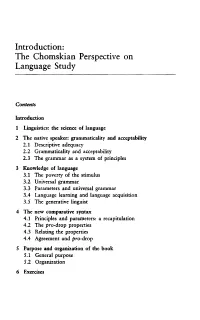

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

Notes on the Development of the Linguistic Society of America 1924 To

NOTES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LINGUISTIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA 1924 TO 1950 MARTIN JOOS for JENNIE MAE JOOS FORE\\ORO It is important for the reader of this document to know how it came to be written and what function it is intended to serve. In the early 1970s, when the Executive Committee and the Committee on Pub1ications of the linguistic Society of America v.ere planning for the observance of its Golden Anniversary, they decided to sponsor the preparation of a history of the Society's first fifty years, to be published as part of the celebration. The task was entrusted to the three living Secretaries, J M. Cowan{who had served from 1940 to 1950), Archibald A. Hill {1951-1969), and Thomas A. Sebeok {1970-1973). Each was asked to survey the period of his tenure; in addition, Cowan,who had learned the craft of the office from the Society's first Secretary, Roland G. Kent {deceased 1952),was to cover Kent's period of service. At the time, CO'flal'\was just embarking on a new career. He therefore asked his close friend Martin Joos to take on his share of the task, and to that end gave Joos all his files. Joos then did the bulk of the research and writing, but the~ conferred repeatedly, Cowansupplying information to which Joos v.t>uldnot otherwise have had access. Joos and HiU completed their assignments in time for the planned publication, but Sebeok, burdened with other responsibilities, was unable to do so. Since the Society did not wish to bring out an incomplete history, the project was suspended. -

Revisiting the Insular Celtic Hypothesis Through Working Towards an Original Phonetic Reconstruction of Insular Celtic

Mind Your P's and Q's: Revisiting the Insular Celtic hypothesis through working towards an original phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic Rachel N. Carpenter Bryn Mawr and Swarthmore Colleges 0.0 Abstract: Mac, mac, mac, mab, mab, mab- all mean 'son', inis, innis, hinjey, enez, ynys, enys - all mean 'island.' Anyone can see the similarities within these two cognate sets· from orthographic similarity alone. This is because Irish, Scottish, Manx, Breton, Welsh, and Cornish2 are related. As the six remaining Celtic languages, they unsurprisingly share similarities in their phonetics, phonology, semantics, morphology, and syntax. However, the exact relationship between these languages and their predecessors has long been disputed in Celtic linguistics. Even today, the battle continues between two firmly-entrenched camps of scholars- those who favor the traditional P-Celtic and Q-Celtic divisions of the Celtic family tree, and those who support the unification of the Brythonic and Goidelic branches of the tree under Insular Celtic, with this latter idea being the Insular Celtic hypothesis. While much reconstructive work has been done, and much evidence has been brought forth, both for and against the existence of Insular Celtic, no one scholar has attempted a phonetic reconstruction of this hypothesized proto-language from its six modem descendents. In the pages that follow, I will introduce you to the Celtic languages; explore the controversy surrounding the structure of the Celtic family tree; and present a partial phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic through the application of the comparative method as outlined by Lyle Campbell (2006) to self-collected data from the summers of2009 and 2010 in my efforts to offer you a novel perspective on an on-going debate in the field of historical Celtic linguistics. -

The$Irish$Language$And$Everyday$Life$ In#Derry!

The$Irish$language$and$everyday$life$ in#Derry! ! ! ! Rosa!Siobhan!O’Neill! ! A!thesis!submitted!in!partial!fulfilment!of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of! Doctor!of!Philosophy! The!University!of!Sheffield! Faculty!of!Social!Science! Department!of!Sociological!Studies! May!2019! ! ! i" " Abstract! This!thesis!explores!the!use!of!the!Irish!language!in!everyday!life!in!Derry!city.!I!argue!that! representations!of!the!Irish!language!in!media,!politics!and!academic!research!have! tended!to!overKidentify!it!with!social!division!and!antagonistic!cultures!or!identities,!and! have!drawn!too!heavily!on!political!rhetoric!and!a!priori!assumptions!about!language,! culture!and!groups!in!Northern!Ireland.!I!suggest!that!if!we!instead!look!at!the!mundane! and!the!everyday!moments!of!individual!lives,!and!listen!to!the!voices!of!those!who!are! rarely!heard!in!political!or!media!debate,!a!different!story!of!the!Irish!language!emerges.! Drawing!on!eighteen!months!of!ethnographic!research,!together!with!document!analysis! and!investigation!of!historical!statistics!and!other!secondary!data!sources,!I!argue!that! learning,!speaking,!using,!experiencing!and!relating!to!the!Irish!language!is!both!emotional! and!habitual.!It!is!intertwined!with!understandings!of!family,!memory,!history!and! community!that!cannot!be!reduced!to!simple!narratives!of!political!difference!and! constitutional!aspirations,!or!of!identity!as!emerging!from!conflict.!The!Irish!language!is! bound!up!in!everyday!experiences!of!fun,!interest,!achievement,!and!the!quotidian!ebbs! and!flows!of!daily!life,!of!getting!the!kids!to!school,!going!to!work,!having!a!social!life!and! -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

The Irish Language in Education in Northern Ireland 2Nd Edition

Irish The Irish language in education in Northern Ireland 2nd edition This document was published by Mercator-Education with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the European Commission (DG XXII: Education, Training and Youth) ISSN: 1570-1239 © Mercator-Education, 2004 The contents of this publication may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to Mercator- Education: European network for regional or minority languages and education. Mercator-Education P.O. Box 54 8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands tel. +31- 58-2131414 fax: + 31 - 58-2131409 e-mail: [email protected] website://www.mercator-education.org This regional dossier was originally compiled by Aodán Mac Póilin from Ultach Trust/Iontaobhas Ultach and Mercator Education in 1997. It has been updated by Róise Ní Bhaoill from Ultach Trust/Iontaobhas Ultach in 2004. Very helpful comments have been supplied by Dr. Lelia Murtagh, Department of Psycholinguistics, Institúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann (ITE), Dublin. Unless stated otherwise the data reflect the situation in 2003. Acknowledgment: Mo bhuíochas do mo chomhghleacaithe in Iontaobhas ULTACH, do Liz Curtis, agus do Sheán Ó Coinn, Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta as a dtacaíocht agus a gcuidiú agus mé i mbun na hoibre seo, agus don Roinn Oideachas agus an Roinn Fostaíochta agus Foghlama as an eolas a cuireadh ar fáil. Tsjerk Bottema has been responsible for the publication of the Mercator regional dossiers series from January 2004 onwards. Contents Foreword ..................................................1 1. Introduction .........................................2 2. Pre-school education .................................13 3. Primary education ...................................16 4. Secondary education .................................19 5. Further education ...................................22 6. -

Corpas Na Gaeilge (1882-1926): Integrating Historical and Modern

Corpas na Gaeilge (1882-1926): Integrating Historical and Modern Irish Texts Elaine Uí Dhonnchadha3, Kevin Scannell7, Ruairí Ó hUiginn2, Eilís Ní Mhearraí1, Máire Nic Mhaoláin1, Brian Ó Raghallaigh4, Gregory Toner5, Séamus Mac Mathúna6, Déirdre D’Auria1, Eithne Ní Ghallchobhair1, Niall O’Leary1 1Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, Ireland 2National University of Ireland Maynooth, Ireland 3Trinity College Dublin, Ireland 4Dublin City University, Ireland 5Queens University Belfast, Northern Ireland 6University of Ulster, Northern Ireland 7Saint Louis University, Missouri, USA E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the processing of a corpus of seven million words of Irish texts from the period 1882-1926. The texts which have been captured by typing or optical character recognition are processed for the purpose of lexicography. Firstly, all historical and dialectal word forms are annotated with their modern standard equivalents using software developed for this purpose. Then, using the modern standard annotations, the texts are processed using an existing finite-state morphological analyser and part-of-speech tagger. This method enables us to retain the original historical text, and at the same time have full corpus-searching capabilities using modern lemmas and inflected forms (one can also use the historical forms). It also makes use of existing NLP tools for modern Irish, and enables integration of historical and modern Irish corpora. Keywords: historical corpus, normalisation, standardisation, natural language processing, Irish, Gaeilge 1. -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

Preservation of Original Orthography in the Construction of an Old Irish Corpus

Preservation of Original Orthography in the Construction of an Old Irish Corpus. Adrian Doyle, John P. McCrae, Clodagh Downey National University of Ireland Galway [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Irish was one of the earliest vernacular European languages to have been written using the Latin alphabet. Furthermore, there exists a relatively large corpus of Irish language text dating to this Old Irish period (c. 700 – c 950). Beginning around the turn of the twentieth century, a large amount of study into Old Irish revealed a highly standardised language with a rich morphology, and often creative orthography. While Modern Irish enjoys recognition from the Irish state as the first official language, and from the EU as a full official and working language, Old Irish is almost incomprehensible to most modern speakers, and remains extremely under-resourced. This paper will examine considerations which must be given to aspects of orthography and palaeography before the text of a historical manuscript can be represented in digital format. Based on these considerations the argument will be presented that digitising the text of the Würzburg glosses as it appears in Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus will enable the use of computational analysis to aid in current areas of linguistic research by preserving original orthographical information. The process of compiling the digital corpus, including considerations given to preservation of orthographic information during this process, will then be detailed. Keywords: manuscripts, palaeography, orthography, digitisation, optical character recognition, Python, Unicode, morphology, Old Irish, historical languages glosses]” (2006, p.10). Before any text can be deemed 1.