Oral Sequelae of Chronic Neutrophil Defects: Case Report of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neutropenia Fact Sheet

Neutropenia in Barth Syndrome i ii (Chronic, Cyclic or Intermittent) What problems can Neutropenia cause? Neutrophils are the main white blood cell for fighting or preventing bacterial or fungal infections. They may be referred to as polymorphonuclear cells (polys or PMNs), white cells with segmented nuclei (segs), or neutrophils in the complete blood cell count (CBC) report. Immature neutrophils are referred to as bands. When someone is neutropenic (an abnormally low level of neutrophils in the blood), the risk of infection increases. The absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is a measure of the total number of neutrophils present in the blood. When the ANC is less than 1,000, the risk of infection increases. Most infections occur in the ears, skin or throat and to a lesser extent, the chest. These infections can be very serious and may require antibiotics to clear infections. When someone with Barth syndrome is neutropenic his defenses are weakened, he is likely to become seriously ill more quickly than someone with a normal neutrophil count. Tips: • No rectal temperatures as any break in the skin can lead to an infection. • If the individual has a temperature > 100.4° F (38° C) or has infectious symptoms, the primary physician or hematologist should be notified. The individual may need to be seen. • If the individual has a temperature of 100.4° F (38° C) – 100.5° F (38.05° C)> 8 hours or a temperature > 101.5° F (38.61° C), an immediate examination by the physician is warranted. Some or all of the following studies may be ordered: CBC with differential and ANC Urinalysis Blood, urine, and other appropriate cultures C-Reactive Protein Echocardiogram if warranted • The physician may suggest antibiotics (and G-CSF if the ANC is low) for common infections such as otitis media, stomatitis. -

THE PATHOLOGY of BONE MARROW FAILURE Roos Leguit, Jan G Van Den Tweel

THE PATHOLOGY OF BONE MARROW FAILURE Roos Leguit, Jan G van den Tweel To cite this version: Roos Leguit, Jan G van den Tweel. THE PATHOLOGY OF BONE MARROW FAILURE. Histopathology, Wiley, 2010, 57 (5), pp.655. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03612.x. hal-00599534 HAL Id: hal-00599534 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00599534 Submitted on 10 Jun 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Histopathology THE PATHOLOGY OF BONE MARROW FAILURE ForJournal: Histopathology Peer Review Manuscript ID: HISTOP-02-10-0090 Manuscript Type: Review Date Submitted by the 08-Feb-2010 Author: Complete List of Authors: Leguit, Roos; UMC utrecht, Pathology van den Tweel, Jan; UMC Utrecht, Pathology bone marrow, histopathology, myelodysplastic syndromes, Keywords: inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, trephine biopsy Published on behalf of the British Division of the International Academy of Pathology Page 1 of 40 Histopathology THE PATHOLOGY OF BONE MARROW FAILURE Roos J Leguit & Jan G van den Tweel University Medical Centre Utrecht Department of Pathology H4.312 Heidelberglaan 100 For Peer Review 3584 CX Utrecht The Netherlands Running title: Pathology of bone marrow failure Keywords: bone marrow, histopathology, myelodysplastic syndromes, inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, trephine biopsy. -

Pediatric Oral Pathology. Soft Tissue and Periodontal Conditions

PEDIATRIC ORAL HEALTH 0031-3955100 $15.00 + .OO PEDIATRIC ORAL PATHOLOGY Soft Tissue and Periodontal Conditions Jayne E. Delaney, DDS, MSD, and Martha Ann Keels, DDS, PhD Parents often are concerned with “lumps and bumps” that appear in the mouths of children. Pediatricians should be able to distinguish the normal clinical appearance of the intraoral tissues in children from gingivitis, periodontal abnormalities, and oral lesions. Recognizing early primary tooth mobility or early primary tooth loss is critical because these dental findings may be indicative of a severe underlying medical illness. Diagnostic criteria and .treatment recommendations are reviewed for many commonly encountered oral conditions. INTRAORAL SOFT-TISSUE ABNORMALITIES Congenital Lesions Ankyloglossia Ankyloglossia, or “tongue-tied,” is a common congenital condition characterized by an abnormally short lingual frenum and the inability to extend the tongue. The frenum may lengthen with growth to produce normal function. If the extent of the ankyloglossia is severe, speech may be affected, mandating speech therapy or surgical correction. If a child is able to extend his or her tongue sufficiently far to moisten the lower lip, then a frenectomy usually is not indicated (Fig. 1). From Private Practice, Waldorf, Maryland (JED); and Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Dentistry, Duke Children’s Hospital, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MAK) ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ PEDIATRIC CLINICS OF NORTH AMERICA VOLUME 47 * NUMBER 5 OCTOBER 2000 1125 1126 DELANEY & KEELS Figure 1. A, Short lingual frenum in a 4-year-old child. B, Child demonstrating the ability to lick his lower lip. Developmental Lesions Geographic Tongue Benign migratory glossitis, or geographic tongue, is a common finding during routine clinical examination of children. -

My Beloved Neutrophil Dr Boxer 2014 Neutropenia Family Conference

The Beloved Neutrophil: Its Function in Health and Disease Stem Cell Multipotent Progenitor Myeloid Lymphoid CMP IL-3, SCF, GM-CSF CLP Committed Progenitor MEP GMP GM-CSF, IL-3, SCF EPO TPO G-CSF M-CSF IL-5 IL-3 SCF RBC Platelet Neutrophil Monocyte/ Basophil B-cells Macrophage Eosinophil T-Cells Mast cell NK cells Mature Cell Dendritic cells PRODUCTION AND KINETICS OF NEUTROPHILS CELLS % CELLS TIME Bone Marrow: Myeloblast 1 7 - 9 Mitotic Promyelocyte 4 Days Myelocyte 16 Maturation/ Metamyelocyte 22 3 – 7 Storage Band 30 Days Seg 21 Vascular: Peripheral Blood Seg 2 6 – 12 hours 3 Marginating Pool Apoptosis and ? Tissue clearance by 0 – 3 macrophages days PHAGOCYTOSIS 1. Mobilization 2. Chemotaxis 3. Recognition (Opsonization) 4. Ingestion 5. Degranulation 6. Peroxidation 7. Killing and Digestion 8. Net formation Adhesion: β 2 Integrins ▪ Heterodimer of a and b chain ▪ Tight adhesion, migration, ingestion, co- stimulation of other PMN responses LFA-1 Mac-1 (CR3) p150,95 a2b2 a CD11a CD11b CD11c CD11d b CD18 CD18 CD18 CD18 Cells All PMN, Dendritic Mac, mono, leukocytes mono/mac, PMN, T cell LGL Ligands ICAMs ICAM-1 C3bi, ICAM-3, C3bi other other Fibrinogen other GRANULOCYTE CHEMOATTRACTANTS Chemoattractants Source Activators Lipids PAF Neutrophils C5a, LPS, FMLP Endothelium LTB4 Neutrophils FMLP, C5a, LPS Chemokines (a) IL-8 Monocytes, endothelium LPS, IL-1, TNF, IL-3 other cells Gro a, b, g Monocytes, endothelium IL-1, TNF other cells NAP-2 Activated platelets Platelet activation Others FMLP Bacteria C5a Activation of complement Other Important Receptors on PMNs ñ Pattern recognition receptors – Detect microbes - Toll receptor family - Mannose receptor - bGlucan receptor – fungal cell walls ñ Cytokine receptors – enhance PMN function - G-CSF, GM-CSF - TNF Receptor ñ Opsonin receptors – trigger phagocytosis - FcgRI, II, III - Complement receptors – ñ Mac1/CR3 (CD11b/CD18) – C3bi ñ CR-1 – C3b, C4b, C3bi, C1q, Mannose binding protein From JG Hirsch, J Exp Med 116:827, 1962, with permission. -

:.. ;}.·:···.·;·1 Congenital Neutropenia

C HAP T E R 13 >;:.. ;}.·:···.·;·1 CONGENITAL NEUTROPENIA Jill M. Watanabe, MD, MPH, and David C. Dale, MD defined by a neutrophil count less than 1500 cellS/ilL; KEY POINTS beyond 10 years of age, neutropenia is defined by a neu trophil count less' than 1800 cells//1L in persons of white Congenital Neutropenia and Asian descent. 1 In persons of African descent, neu tropenia is defined by a count of 800--1000 cells//1L. 1 (& Congenital neutropenia encompasses a heterogeneous group of The severity and duration of neutropenia are also clin iuheri ted diseases. ically important. Mild neutropenia is usually defined by • The genetic mutations causing congenital neutropenia may neutrophil counts of 1000-1500 cells//1L, moderate neu have an isolated effect on the bone marrow but can also affect tropenia is 500-1000 cells//1L, and severe neutropenia one or more other organ systems. is less than 500 cells//1L. Acute neutropenia usually is present for only 5-10 days; neutropenia is chronic if its (& The genetic defects underlying the diseases that cause con duration is at least several weeks. Almost all congenital genital neutropenia have been rapidly identified over the past neutropenias are chronic neutropenia. decade. The characteristics and causes of congenital neu (& Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor has dramatically tropenia are shown in Tables 13-1 and 13-2, and an algo improved the prognosis for children with congenital rithm for their diagnosis is presented in Figure 13-1. neutropenia. SEVERE CONGENITAL NEUTROPENIA Patient'; with severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) typi cally present with recurrent bacterial infections and neutrophil count'> persistently less than 200 cells//1L. -

Neutropenia : an Analysis of the Risk Factors for Infection Steven Ira Rosenfeld Yale University

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library School of Medicine 1980 Neutropenia : an analysis of the risk factors for infection Steven Ira Rosenfeld Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl Recommended Citation Rosenfeld, Steven Ira, "Neutropenia : an analysis of the risk factors for infection" (1980). Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library. 3087. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3087 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Medicine at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEUTROPENIA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE RISK FACTORS FOR INFECTION by Steven Ira Rosenfeld B.A. Johns Hopkins University 1976 A Thesis Submitted to The Yale University School of Medicine In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Medicine 1980 Med Li^> Ya ABSTRACT The risk factors for infection were evaluated retrospectively in 107 neutropenic patients without underlying malignancy or cyto¬ toxic drug therapy. Neutrophil count was an independent risk factor for infection, with the incidence of infection increasing as the neutrophil count decreased. The critical neutrophil count, below which the incidence of infection was significantly increased was 250/mnr*, (p<.001). Eighty five percent of the <250 group entered with, or developed infection. Additional risk factors for infection included increased duration of neutropenia, age less than 1 year old, male sex, hypogammaglobulinemia, and recent antibiotic therapy. -

Sign In: Pemphigus.Org/Form

3/27/2018 Pemphigus and Pemphigoid –The Unique Role of the Dental Professional Dr. Carol Anne Murdoch‐Kinch Sign In: pemphigus.org/form The International Pemphigus & Pemphigoid Foundation (IPPF) kindly asks all attendees to sign‐in using the link provided. The above sign‐in link is optional and NOT required to receive CE credits (if being offered). Information collected will be used by the IPPF. www.PutItOnYourRadar.org The IPPF Awareness Program is generously funded by the Sy Syms Foundation and the Unger Family. The International Pemphigus & Pemphigoid Foundation (IPPF) advises audience members of the risks of using limited knowledge gained from this course when in practice. VISION To find a cure for pemphigus and pemphigoid EARLY DIAGNOSIS AWARENESS PROGRAM It takes the average pemphigus / pemphigoid patient 5 healthcare providers and 10 months to obtain a correct diagnosis. Help us reduce diagnostic delays! 1 3/27/2018 PATIENT SUPPORT SERVICES • Physician Referral List • Peer Health Coaches • Patient Education Calls • Support Group Meetings • Quarterly Newsletter • Annual Patient Education Conference www.pemphigus.org RESOURCES FOR DENTAL PROFESSIONALS • CE courses • Patient speakers at dental schools • Educational materials • Comprehensive disease information www.PutItOnYourRadar.org PLEASE STOP BY THE IPPF EXHIBIT BOOTH #008 Meet a patient and learn more Thank You! 2 3/27/2018 Key Concepts • Oral lesions may be the first or only sign of vesiculobullous diseases, including pemphigus and pemphigoid: “First to show and last to go” -

Patient Handbook 3-2-10

∑ UNDERSTANDING SEVERE CHRONIC NEUTROPENIA A Handbook for Patients and Their Families Written for the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry By: Audrey Anna Bolyard, R.N., B.S. Laurence Boxer, M.D. Tammy Cottle Carole Edwards, R.G.N/R.S.C.N., BSc. Sally Kinsey, M.D. Peter Newburger, M.D. Beate Schwinzer, Ph.D. Cornelia Zeidler, M.D. Understanding Severe Chronic Neutropenia 1 A handbook for patients and their families Revised February 2010 ∑ Contents Page Introduction 3 How Blood is Formed 3 What is Neutropenia? 4 Overview: Diagnosis & Treatment of Severe Chronic Neutropenia 5 Risk of Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Leukemia 6 Risk of Osteopenia/Osteoporosis 7 Types of Severe Chronic Neutropenia 7 Severe Congenital Neutropenia 8 Cyclic Neutropenia 8 Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome 9 Metabolic disorders with neutropenia 10 Glycogen-Storage Disease Type 1b 10 Barth Syndrome 10 Idiopathic Neutropenia 10 Autoimmune Neutropenia 10 Other Conditions Associated with Neutropenia 11 Genetics of Severe Congenital Neutropenia 11 Diagnostic Tests Used in Severe Chronic Neutropenia 12 Blood Count Monitoring 12 Other Blood Tests 12 Bone Marrow Aspirate / Trephine Biopsy 12 Cytogenetic Evaluation 12 Investigations in Other Conditions 12 Treatment for Severe Chronic Neutropenia 13 Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF) 14 Hematopoietic Stem Cell (Bone Marrow) Transplant 15 Other Treatments 15 Long Term Management of SCN 16 Bone Marrow Monitoring 17 Pregnancy 17 Psychosocial Issues 17 The Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry 18 Support Groups 20 Frequently Asked Questions and Answers 20 Information Form for Schools 24 Glossary 25 Understanding Severe Chronic Neutropenia 2 A handbook for patients and their families Revised February 2010 ∑ Introduction Severe chronic neutropenia (SCN) is the name given to a group of conditions in which neutropenia is the primary problem. -

Oral Ulcers Presentation in Systemic Diseases: an Update

Open Access Maced J Med Sci electronic publication ahead of print, published on October 10, 2019 as https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.689 ID Design Press, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.689 eISSN: 1857-9655 Review Article Oral Ulcers Presentation in Systemic Diseases: An Update Sadia Minhas1, Aneequa Sajjad1, Muhammad Kashif2, Farooq Taj3, Hamed Al Waddani4, Zohaib Khurshid5* 1Department of Oral Pathology, Akhtar Saeed Dental College, Lahore, Pakistan; 2Department of Oral Pathology, Bakhtawar Amin Medical & Dental College, Multan, Pakistan; 3Department of Prosthetic, Khyber Medical University Institute of Dental Sciences, Kohat, Pakistan; 4Department of Medicine and Surgery, College of Dentistry, King Faisal University, Hofuf, Al- Ahsa Governorate, Saudi Arabia; 5Department of Prosthodontics and Dental Implantology, College of Dentistry, King Faisal University, Hofuf, Al-Ahsa Governorate, Saudi Arabia Abstract Citation: Minhas S, Sajjad A, Kashif M, Taj F, Al BACKGROUND: Diagnosis of oral ulceration is always challenging and has been the source of difficulty because Waddani H, Khurshid Z. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. of the remarkable overlap in their clinical presentations. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.689 Keywords: Oral ulcer; Infections; Vesiculobullous lesion; AIM: The objective of this review article is to provide updated knowledge and systemic approach regarding oral Traumatic ulcer; Systematic disease ulcers diagnosis depending upon clinical picture while excluding the other causative causes. *Correspondence: Zohaib Khurshid. Department of Prosthodontics and Dental Implantology, College of Dentistry, King Faisal University, Hofuf, Al-Ahsa METHODS: For this, specialised databases and search engines involving Science Direct, Medline Plus, Scopus, Governorate, Saudi Arabia. -

Early Tooth Loss Due to Cyclic Neutropenia: Long-Term Follow-Up of One Patient

.................... ................................................ ARTICLE Marcio A. da Fonseca, DDS, MS, Fernanda Fontes, DDS, MS Early tooth loss due to cyclic neutropenia: long-term follow-up of one patient the first line of defense against infec- In young patients with abnormal entists and dental hygienists tion, their depletion can be fatal, loosening of teeth and periodontal play an important role in the although the child may appear healthy breakdown, dental professionals early detection of diseases or between cycles.6 The diagnosis is made should consider a wide range of etio- D conditions whose initial signs are by documentation of two cycles of logical factors/diseases, analyze dif- seen in the oral cavity. In cases of decreased neutrophil count observed ferential diagnoses, and make appro- abnormal loosening of teeth and in complete blood count (CBC) tests priate referrals. The long-term oral periodontal breakdown without an done twice weekly for 6 weeks.' and dental follow-up of a female apparent cause, the dental profes- This report reviews the oral mani- patient diagnosed in early infancy sional must be prepared to investi- festations of CN and presents the case with cyclic neutropenia is reviewed, gate a wide range of differential diag- of an adult female who has been fol- and recommendationsfor care are noses, recommend further investiga- lowed by our pediatric dental service discussed. tion, and make appropriate referrals. since early infancy. Cyclic neutropenia (CN) is charac- terized by a transient decrease in the neutrophil count, with a periodicity Case report of approximately 21 days (range, 14 Shortly after birth, in February, 1978, to 36 days).',2 It is inherited as an our patient had pustular skin infec- autosomal-dominant condition in tions from which Staphylococcus about one-third of the patients, with uureus was cultured, followed by sev- the remaining cases having an eral episodes of fungal diaper rash unclear mode of inheritance.' CN is and otitis media (OM). -

Oral Manifestations of Systemic Diseases: Overview, Gastrointestinal Diseases, Nutritional Disease 12/09/16, 11:27

Oral Manifestations of Systemic Diseases: Overview, Gastrointestinal Diseases, Nutritional Disease 12/09/16, 11:27 Oral Manifestations of Systemic Diseases Author: Heather C Rosengard, MPH; Chief Editor: Dirk M Elston, MD more... Updated: Jul 27, 2016 Overview The oral cavity plays a critical role in numerous physiologic processes, including digestion, respiration, and speech. It is also unique for the presence of teeth and mucosa. The mouth is frequently involved in conditions that affect the skin, but it is also affected by many systemic diseases. Oral involvement may precede or follow the appearance of findings at other locations. This article is intended as a general overview of conditions with oral manifestations of systemic diseases. It is not intended to provide details about the diagnosis and management of these conditions. Many of these conditions have excellent full- length Medscape Drugs & Diseases articles, which are linked herein. Gastrointestinal Diseases The oral cavity is the portal of entry to the GI tract and is lined with stratified squamous epithelium. The oral cavity is often involved in conditions that affect the GI tract. Both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease are classified as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). While Crohn disease can affect any part of the GI tract (from the oral cavity to the anus), inflammation in UC is generally restricted to the colon and is specifically limited to the mucosa and submucosa. Ulcerative colitis UC is characterized by periods of exacerbation and remission, and, generally, oral lesions coincide with exacerbations of the colonic disease. Lesions in the colon consist of areas of hemorrhage and ulceration, along with abscesses. -

Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing

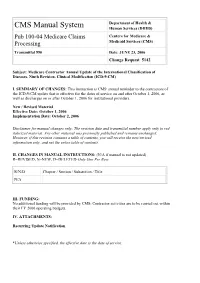

Department of Health & CMS Manual System Human Services (DHHS) Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Centers for Medicare & Processing Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 990 Date: JUNE 23, 2006 Change Request 5142 Subject: Medicare Contractor Annual Update of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) I. SUMMARY OF CHANGES: This instruction is CMS' annual reminder to the contractors of the ICD-9-CM update that is effective for the dates of service on and after October 1, 2006, as well as discharges on or after October 1, 2006 for institutional providers. New / Revised Material Effective Date: October 1, 2006 Implementation Date: October 2, 2006 Disclaimer for manual changes only: The revision date and transmittal number apply only to red italicized material. Any other material was previously published and remains unchanged. However, if this revision contains a table of contents, you will receive the new/revised information only, and not the entire table of contents. II. CHANGES IN MANUAL INSTRUCTIONS: (N/A if manual is not updated) R=REVISED, N=NEW, D=DELETED-Only One Per Row. R/N/D Chapter / Section / Subsection / Title N/A III. FUNDING: No additional funding will be provided by CMS; Contractor activities are to be carried out within their FY 2006 operating budgets. IV. ATTACHMENTS: Recurring Update Notification *Unless otherwise specified, the effective date is the date of service. Attachment – Recurring Update Notification Pub. 100-04 Transmittal: 990 Date: June 23, 2006 Change Request 5142 SUBJECT: Medicare Contractor Annual Update of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) I.