SD Was on the Cards: P.R.S. Foli's Fortune-Telling by Cards (1904) In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinochle-Rules.Pdf

Pinochle From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pinochle (sometimes pinocle, or penuchle) is a trick-taking Pinochle game typically for two, three or four players and played with a 48 card deck. Derived from the card game bezique, players score points by trick-taking and also by forming combinations of cards into melds. It is thus considered part of a "trick-and- meld" category which also includes a cousin, belote. Each hand is played in three phases: bidding, melds, and tricks. In some areas of the United States, such as Oklahoma and Texas, thumb wrestling is often referred to as "pinochle". [citation needed] The two games, however, are not related. The jack of diamonds and the queen of spades are Contents the "pinochle" meld of pinochle. 1 History Type Trick-taking 2 The deck Players 4 in partnerships or 3 3 Dealing individually, variants exist for 2- 4 The auction 6 or 8 players 5 Passing cards 6 Melding Skills required Strategy 7 Playing tricks Social skills 8 Scoring tricks Teamwork 9 Game variations 9.1 Two-handed Pinochle Card counting 9.2 Three-handed Pinochle Cards 48 (double 24 card deck) or 80 9.3 Cutthroat Pinochle (quadruple 20 card deck) 9.4 Four-handed Pinochle 9.5 Five-handed and larger Pinochle Deck Anglo-American 9.6 Check Pinochle 9.7 Double-deck Pinochle Play Clockwise 9.8 Racehorse Pinochle Card rank A 10 K Q J 9 9.9 Double-deck Pinochle for eight players (highest to 10 See also lowest) 11 References 12 External links Playing time 1 to 5 hours Random chance Medium History Related games Pinochle derives from the game bezique. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1990

Tangtewqpd . urlake erform miracles They dissolve the stresses and strains of everyday living. The Berkshires' most successful 4-seasons hideaway, a gated private enclave with V^-mile lake frontage, golf and olympic pool, tennis, Fitness Center, lake lodge —all on the lake. Carefree 3 -and 4- Your bedroom country condominiums with luxury amenities and great skylights, fireplaces, decks. Minutes from Jiminy Peak, Brodie Berkshire Mountain, Tanglewood, Jacob's Pillow, Canyon Ranch. In the $200s. escape SEE FURNISHED MODELS, SALES CENTER TODAY. (413) 499-0900 or Tollfree (800) 937-0404 LAKECREST Dir: Rte. 7 to Lake Pontoosuc. Turn left at Lakecrest sign 7 DIRECTLY ON LAKE PONTOOSUC on Hancock Rd. /10 -mile to Ridge Ave. Right turn to Lakecrest gated entry. Ct££ h\> Prncfw Seiji Ozawa (TMC '60), Music Director Carl St. Clair (TMC '85) and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Ninth Season, 1989-90 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus President J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Mrs. John L. Grandin Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Francis W Hatch, Jr. Richard A. Smith Julian Cohen Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. George I. Kaplan William F. Thompson Mrs. Michael H. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T Zervas Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. -

SAXTON-THESIS.Pdf

Abstract Grotesque Subjects: Dostoevsky and Modern Southern Fiction, 1930-1960 by Benjamin T. Saxton As a reassessment of the southern grotesque, this dissertation places Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers, and William Faulkner in context and conversation with the fiction of Fyodor Dostoevsky. While many southern artists and intellectuals have testified to his importance as a creative model and personal inspiration, Dostoevsky’s relationship to southern writers has rarely been the focus of sustained analysis. Drawing upon Mikhail Bakhtin’s deeply positive understanding of grotesque realism, I see the grotesque as an empowering aesthetic strategy that, for O’Connor, McCullers, and Faulkner, captured their characters’ unfinished struggles to achieve renewal despite alienation and pain. My project suggests that the preponderance of a specific type of character in their fiction—a physically or mentally deformed outsider—accounts for both the distinctiveness of the southern grotesque and its affinity with Dostoevsky’s artistic approach. His grotesque characters, consequently, can fruitfully illuminate the misfits, mystics, and madmen who stand at the heart—and the margins—of modern southern fiction. By locating one source of the southern grotesque in Dostoevsky’s fiction, I assume that the southern literary imagination is not directed incestuously inward toward its southern past but also outward beyond the nation or even the hemisphere. This study thus offers one of the first evaluations of Dostoevsky’s impact on southern writers as a group. Acknowledgements I am very thankful for my professors at Rice University for their intellectual stimulation and continued support. My advisor, Colleen Lamos, has offered me guidance and encouragement on every step of the way. -

Sons of the Gun

1 Wild Cards Sons of the Gun Table of Contents The Legend… … pg. 03 About Wild Cards ... …pg. 04 Attaining, Owning, and Passing the Cards… ...pg. 05 Playing Wild Cards… ...pg. 06 Story: The Last Stand At Tombstone… … pg. 09 History of the Wild Cards World… … pg. 15 The Fifty Four Cards… …pg. 20 The Spades… ...pg. 21 The Diamonds… ...pg. 27 The Clubs… ...pg. 33 The Hearts… ...pg. 39 The Jokers… ...pg. 45 Acknowledgements… … pg. 47 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: Y ou are free to share and adapt this material for any purpose, including commercially, as long as you give attribution. Rules by Sean "Mac" McClellan. All lore text was created by a variety of folks and I make no claim of ownership of it - please see the “Acknowledgements” section for a list of contributors I’ve managed to chronicle thus far. 2 Wild Cards: Sons of the Gun The Legend... There are whispers. Half truths and tall tales. To be honest no man knows where the Cards came from. No mortal man, kennit? All that is agreed upon is one day they started to appear, and the world changed. To hear it told, there are only so many true Guns in the world. Guns with a capital G. The Fabled Fifty Four. Sure you can find the odd shooting iron, crafted by some smith of supreme skill. Maybe even purchase a genuine Smythe, not the mass produced crap, but one the old man made himself. More common a slugthrower, those bastard children of inspiration that many a would-be 'Slinger claims is a weapon true. -

Fortune-Telling by Cards

Fortune-Telling by Cards By Professor P. R. S. Foli Author of "Fortune Teller" "Dream Book," etc. R. P. FENNO & COMPANY 18 East 17th Street, New York [first published 1915, this edition 1920?] Contents CHAPTER I HOW WE GOT OUR PACK OF CARDS Where do they come from?—The Romany Folk—Were they made in Europe?—Suits and signs—The power of cards—Their charm and interest—Necessity for sympathy—Value of Cartomancy CHAPTER II WHAT THE INDIVIDUAL CARDS SIGNIFY Two systems—The English method—The foreign—Significations of the cards—Hearts— Diamonds—Clubs—Spades—A short table—Mystic meanings CHAPTER III THE SELECTED PACK OF THIRTY-TWO CARDS Reduced pack generally used—How to indicate reversed cards—Meaning of Hearts— Diamonds—Clubs—Spades CHAPTER IV THE SIGNIFICATION OF QUARTETTES, TRIPLETS, AND PAIRS Combinations of court cards—Combinations of plain cards—Various cards read together— General meaning of the several suits—Some lesser points to notice CHAPTER V WHAT THE CARDS CAN TELL OF THE PAST, THE PRESENT, AND THE FUTURE A simple method—What the cards say—The Present—The Future CHAPTER VI YOUR FORTUNE IN TWENTY-ONE CARDS A reduced pack—An example—The three packs—The surprise CHAPTER VII COMBINATION OF SEVENS A method with selected cards—General rules—How to proceed—Reading of the cards— Signification of cards—Some combinations—A typical example—Further inquiries—The seven packs CHAPTER VIII ANOTHER METHOD WITH THIRTY-TWO CARDS General outline—Signification of cards—How to consult the cards—An illustration—Its reading CHAPTER IX A FRENCH METHOD French system—The reading—An example CHAPTER X THE GRAND STAR The number of cards may vary—The method—The reading in pairs—Diagram of the Grand Star—An example CHAPTER XI IMPORTANT QUESTIONS. -

Jean Hugard's CARD MANIPULATIONS (Part 4) to Palm

Brought to you by LearnMagicTricks.org Jean Hugard's CARD MANIPULATIONS (Part 4) Visit www.magicforall.com the world's premier download magic site, for all the latest instant download tricks. Plus free downloads, free tutorials and all that's best in magic. This version of Hugard's classic book has been prepared and edited by Magic For All. You may however distribute it in any way you see fit with two small conditions. Firstly you may not alter the ebook in any way, secondly please ensure that this document is distributed only to genuine magicians. To Palm a Number of Cards from the Top Brought to you by LearnMagicTricks.org Palming is probably the weakest spot in the technique of most card workers, both amateur and professional. The most common faults being the manner in which the hand is brought right over the deck, taking off the required cards with a perceptible grabbing action, at the same time telegraphing the movement by throwing the thumb straight upward and, finally, the removal of the hand with the cards in it without any reason at all having been given for the whole action. Under these circumstances it Would have to be a very innocent spectator who did not suspect that some cards had been removed from the pack. To palm cards perfectly the action must be so covered that a spectator who keeps his eyes fixed on the performer's hands can detect no suspicious movement. This is not so difficult as might be imagined and the method that follows is well within the reach of any card handler with a minimum of practice. -

Advantagesof Humans and Machines in the Building of Intelligent Systems Are 'Explained

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 201 337 IR .009 351 AUTHOR Hayes -Roth, Frederick: And Others TITLE 'Knowledge Acquisition, Knowledge Programming, arld Knowledge Refinement. INSTITUTION Rand Corp., Santa Monica, Calif. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Rashington, D.C. EEPORT NO ISBN-0-8330-0195-7; Rand-R-2540-115F PUB,DATE May 80 GRANT MCS77'03273 NOTE 39p. AVAILABLE FROMRand Corporation, Main St., Santa Monica, 2A 90406 ($3.00). EDRS. PRICE HF01 Plus Postage._. PC Not Available from EDRS. -DESCRIPTORS *Artificial Intelligence; *Computers; Informatioa Theory; Man Machine Systems; .*Programing; Research Reports; Systems Development ABSTRACT. This report describes the principal findings and recommendations of a 2-year Rand research projedt on machine-aided knowledge acquisition an -discusses the transfer of expertise from humans to machines, as'weils the functions of planning, debugging', . knowledge .:efineient, andauton moos machine' learning. The relatiie .advantagesof humans and machines in the building of intelligent systems are 'explained. Background and guidance is provided for policymakers concerned with the research and development of machine-based learning systems'. The research method adoptel emphasized iterative refinement of knowledge in' response to actual experience; i.e., a machine's knowledge, was acquired initially from a human who provided enough concepts, constraints, and problem-solving heuristics to'' define some minimal level of performance. Sixty -,tap 'references are listed. (Author/FM) ************************************** -1**.i.*************************** * Reproduciiont supplied by -a: Ahe best that can be `made At' * frOm the origine_ .4.'zumente. ****.******4c*******101c.***,************oz******************************C: U.S, OE PAR.T. :#T Q,. ALT;, EOUCATiC ;It PiT,.f4FtV NAT Iew '17:11',07r-cy THIS °Dap ' .71, IV- P FORO. -

Pinochle Glossary Mostly Single Deck

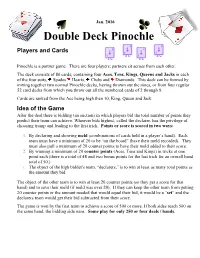

Jan. 2016 Double Deck Pinochle Players and Cards Pinochle is a partner game. There are four players; partners sit across from each other. The deck consists of 80 cards; containing four Aces, Tens, Kings, Queens and Jacks in each of the four suits, Spades Hearts, Clubs and Diamonds. This deck can be formed by mixing together two normal Pinochle decks, having thrown out the nines, or from four regular 52 card decks from which you throw out all the numbered cards of 2 through 9. Cards are ranked from the Ace being high then 10, King, Queen and Jack. Idea of the Game After the deal there is bidding (an auction) in which players bid the total number of points they predict their team can achieve. Whoever bids highest, called the declarer, has the privilege of choosing trump and leading to the first trick. Points or score is scored in two ways: 1. By declaring and showing meld (combinations of cards held in a player’s hand). Each team must have a minimum of 20 to be “on the board” (have their meld recorded). They must also pull a minimum of 20 counter points to have their meld added to their score. 2. By winning a minimum of 20 counter points (Aces, Tens and Kings) in tricks at one point each (there is a total of 48 and two bonus points for the last trick for an overall hand total of 50.) 3. The object of the high bidder's team, “declarers,” is to win at least as many total points as the amount they bid. -

Mla Volume 77 Issue 1 Cover

CONTENTS · MARCH "For Members Only": News and Comment . I. Design for Treachery: The Unferth Intrigue. By JAMES L. ROSIER. 1 II. Naturaleza, Religion y Honra en La Celestina. Por GUSTAVO CORREA. 8 III. King Hamlet's Ghost in Belleforest? By ARTHUR P. STABLER..... ... 18 IV. Jonson and the Neo-Latin Authorities for the Plain Style. By \VESLEY TRIMPI. 21 V. "Eager Thought": Dialectic in Lycidas. By JON S. LAWRy........... 27 VI. Marvell's Horatian Ode. By JOHN 1vf. WALLACE. .................. 33 VII. Verbal Irony in Tom Jones. By ELEANOR N. HUTCHENS.... ........ 46 VIII. A Reading of Wieland. By LARZER ZIFF... ...................... 51 IX. Toward a Revaluation of Goethe's Glitz: The Protagonist. By FRANK G. RyDER.... .. .. .. ...... .. 58 X. Tom Moore and the Edinburgh Review of Christabel, By ELISABETH W. SCHNEIDER.. ....................................... 71 XI. Keats, Milton, and The Fall of Hyperion. By STUART M. SPERRY, JR.. 77 XII. From Earth to Ether: Poe's Flight into Space. By CHARLES O'DONNELL. 85 XIII. The Biblical Sources of Hawthorne's "Roger Malvin's Burial." By W. R. THOMPSON. .. .. .. .. ....... 92 XIV. De Quincey's Revisions in the "Dream-Fugue." By RICHARD H. BYRNS... ............................................ 97 XV. Ruskin in French Criticism: A Possible Reappraisal. By FRANK D. CURTIN.................... ......................... .. 102 XVI. Zola and Busnach: The Temptation of the Stage. By MARTIN KANES 109 XVII. The Pursuit of Form in the Novels of Azorin. By LEONLIVINGSTONE 116 XVIII. "Profusion du soir" and "Le Cimetiere marin." By CHARLES G. WHITING.... ....................................... .. 134 XIX. Aspects of Imagery in Colette: Color and Light. By I. T. OLKEN. .. 140 XX. Psychology in the Early Works of Thomas Mann. -

Bulletin No 12

TH WORLD BRIDGE S E R I E S ORLANDO, FLORIDA | 21ST SEPTEMBER - 6TH OCTOBER 2018 15Editor: Brent Manley • Co-Editors: Barry Rigal, Brian Senior Daily Bulletin Journalists: David Bird, Jos Jacobs, Ron Tacchi • Lay-out Editor: Monica Kümmel Issue No. 12 Tuesday, 2nd October 2018 IT’S A MIXED KNOCKOUT! The 22nd World Computer‐Bridge Championship started on Sunday with the nine bot entries competing in a 32‐board round robin. The top four teams advanced to the semifinal KO, with top finisher Wbridge5 (+9) taking on the fourth place finisher Q‐Plus Bridge and second place Micro Bridge (+4) battling Synrey Bridge. See the results at www.computerbridge.com along with the 22‐year history. Al Levy (arrow), poses with the robot developers. Levy has run the tournament from the beginning. The two-day Swiss qualifying ended on Tuesday with the team led by Nanette Contents Noland in the lead, followed by the Barbara Ferm squad and a team led by Karen McCallum, winner of many world titles, including the 2006 World Mixed Pairs (with BBO Schedule . .2 Matt Granovetter). Playing with Noland are Sabine Auken, Roy Welland, Zia Mahmood, Marion ALL TOGETHER . .3 Michielsen and Mike Passell. Women’s pairs final A - Stanza 6 .4 Ferm’s teammates are Sjoert Brink, Bas Drijver, Simon de Wijs, Christina Lund Madsen and Daniela von Arnim. Mixed Swiss R 3 . .10 McCallum, captain, is playing with Ashley Bach, Sheila Gabay, Victor King and Kit and Sally Woolsey. BARR v 3ST . .13 The event continues today with the round of 64. -

THE USES of GAMES in BRIDESHEAD REVISITED by Daryl Holmes (Nicholls State University)

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER AND STUDIES Volume 30, Number 2 Autumn, 1996 THE USES OF GAMES IN BRIDESHEAD REVISITED By Daryl Holmes (Nicholls State University) While Evelyn W••wgh's Brideshead Revisited has been approached from a variety of perspectives with particular emphasis on the novel as a romance, as an apology for Catholicism, and as an indication of forties sensibilities as infor:ned by the two World Wars, another approach to the novel arises from the striking number of references to James. In addition to the more general references to parlour games, garden games, general post and cards, there are nineteen references to specific games, most of which are either card games or board games. The question of the significance of the game references can be answered by studying the rules of the indi·Jidual games. Of the games actua!!y set up or played, badminton and golf, for 3Xample, are mentioned in passing but neither set up nor ~layed, particular games are chosen to indicate characters' personalities, traits, motivations, and class. They are also used to reinforce the movement of the plot. Further, these games along with psychological games are the finer threads of the larger fabric of the structure of the novel. Games help the narrator to structure his experience within the framework of the World Wars, during and after wrich the narrator along with the other charact8rs in the novel and the people in the world were (and still are) trying to organize their experience. The framework of World War II is in turn part of a larger framework-- the ancient and ongoing cosmic wa.r between good and evil. -

11-29-2019 Queen of Spades.Indd

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY the queen of spades conductor Opera in three acts Vasily Petrenko DEBUT Libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky production and the composer, based on the Elijah Moshinsky story by Alexander Pushkin set and costume designer Friday, November 29, 2019 Mark Thompson 7:30–11:05 PM lighting designer Paul Pyant First time this season choreographer John Meehan revival stage director Peter McClintock The production of The Queen of Spades was made possible by a generous gift from the Lila Acheson and DeWitt Wallace Endowment Fund, established by the founders of The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2019–20 SEASON The 72nd Metropolitan Opera performance of PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY’S the queen of spades conductor Vasily Petrenko DEBUT in order of vocal appearance tchekalinsky the governess Paul Groves* Jill Grove sourin masha Raymond Aceto* Leah Hawkins** count tomsk y / plutus master of ceremonies Alexey Markov Patrick Cook DEBUT hermann chloë Yusif Eyvazov Mané Galoyan DEBUT prince yeletsk y tchaplitsky Igor Golovatenko Arseny Yakovlev** DEBUT naroumov lisa Mikhail Svetlov Lise Davidsen DEBUT This performance is being broadcast the countess catherine the gre at live on Metropolitan Larissa Diadkova Sheila Ricci Opera Radio on SiriusXM channel 75 pauline / daphnis piano solo and streamed at Elena Maximova Lydia Brown* metopera.org. Friday, November 29, 2019, 7:30–11:05PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Tchaikovsky’s