A Discussion on the Phases, Semantics and Syntax of Aspect in the Translation of ‘’Transformation Structurelle, Intégration Régionale Et Mobilisation Des Ressources’’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec 0 1 2009 Libraries

Constraining Credences MASSACHUS TS INS E OF TECHNOLOGY by DEC 0 12009 Sarah Moss A.B., Harvard University (2002) LIBRARIES B.Phil., Oxford University (2004) Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the ARCHIVES MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Apn1 2009 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2009. All rights reserved. A uthor ..... ......... ... .......................... .. ........ Department of Linguistics and Philosophy ... .. April 27, 2009 Certified by...................... ....... .. .............. ......... Robert C. Stalnaker Laure egckefeller Professor of Philosophy Thesis Supervisor Accepted by..... ......... ............ ... ' B r I Alex Byrne Professor of Philosophy Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students Constraining Credences by Sarah Moss Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. April 27, 2009 This dissertation is about ways in which our rational credences are constrained: by norms governing our opinions about counterfactuals, by the opinions of other agents, and by our own previous opinions. In Chapter 1, I discuss ordinary language judgments about sequences of counterfactuals, and then discuss intuitions about norms governing our cre- dence in counterfactuals. I argue that in both cases, a good theory of our judg- ments calls for a static semantics on which counterfactuals have substantive truth conditions, such as the variably strict conditional semantic theories given in STALNAKER 1968 and LEWIS 1973a. In particular, I demonstrate that given plausible assumptions, norms governing our credences about objective chances entail intuitive norms governing our opinions about counterfactuals. I argue that my pragmatic accounts of our intuitions dominate semantic theories given by VON FINTEL 2001, GILLIES 2007, and EDGINGTON 2008. -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

Pronominal Typology & the De Se/De Re Distinction

Pronominal Typology & the de se/de re distinction Pritty Patel-Grosz 1. Introduction This paper investigates how regular pronominal typology interfaces with de se and de re interpretations, and highlights a correlation between strong pronouns (descriptively speaking) and de re interpretations, and weak pronouns and de se interpretations. In order to illustrate this correlation, I contrast different pronominal forms within a single language, null vs. overt pronouns in Kutchi Gujarati, and clitic vs. full pronouns in Austrian Bavarian. I argue that the data presented here provide cross-linguistic comparative support for the idea of a dedicated de se LF as argued for by Percus & Sauerland. The empirical findings in this paper reveal a new observation regarding pronominal typology, namely that stronger pronouns resist a de se construal. Contrastively, the “weaker” a pronoun is (in comparison to other pronouns in the same language), the more likely it is to be interpreted de se. To analyse this, I propose that pronominal strength correlates with structural complexity (in terms of Cardinaletti & Starke 1999), i.e. overt pronouns have more syntactic structure than null pronouns; similarly, non-clitic pronouns have more structure than clitic pronouns. The correlation between de se readings and weakness follows from an analysis in the spirit of Percus & Sauerland (2003a,b), which assumes that de se pronouns are uninterpreted and merely serve to trigger predicate abstraction. Stronger pronouns, which have more structure, can be taken to simply resist being uninterpreted, given that the null hypothesis is that the additional structure has some effect or other on the semantics of the pronoun. -

Understanding Core French Grammar

Understanding Core French Grammar Andrew Betts Lancing College, England Vernon Series in Language and Linguistics Copyright © 2016 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Ascience Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Vernon Series in Language and Linguistics Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947126 ISBN: 978-1-62273-068-1 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respec- tive owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Table of Contents Acknowledgements xi Introduction xiii Chapter 1 Tense Formation 15 1.0 Tenses – Summary 15 1.1 Simple (One-Word) Tenses: 15 1.2 Compound (Two-word) Tenses: 17 2.0 Present Tense 18 2.1 Regular Verbs 18 2.2 Irregular verbs 19 2.3 Difficulties with the Present Tense 19 3.0 Imperfect Tense 20 4.0 Future Tense and Conditional Tense 21 5.0 Perfect Tense 24 6.0 Compound Tense Past Participle Agreement 28 6.1 -

Aspectual Forms in Lutsotso

Languages Research Journal in Modern Languages and Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com/languages-and-literatures & Literatures Research Article Section: Literature, Languages and Criticism This article is published Aspectual forms in Lutsotso by Royallite Global, Kenya in the Research Journal in Modern Languages and Hellen Odera¹ & David Barasa² Literatures, Volume 2, Issue ¹-²Department of Languages and Literature Education, 2, 2021 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya Article Information Correspondence: [email protected] Submitted: 15th Jan 2021 Accepted: 30th Mar 2021 Published: 5th April 2021 Abstract This paper analyses the inflectional category of aspect in Additional information is Lutsotso, a dialect of the Oluluhya macro-language. Using available at the end of the descriptive approach, the paper establishes that there are article a number of inflectional morphemes affixed on the verb https://creativecommons. root to express, e.g. person, number, tense, aspect and org/licenses/by/4.0/ mood. Among these affixes, tense and aspect categories interact largely, hence, it is difficult to study one category To read the paper without referring to the other. While tense and aspect are online, please scan this profoundly connected in Lutsotso, this paper only identifies QR code and describes the inflectional form of aspect. Generally, aspect in Lutsotso relates to the grammatical viewpoints such as the perfective, imperfective and iterative forms. This includes the temporal properties of situations and the situation types as well. Aspect just like other grammatical categories such as tense, mood, person, agreement and number are important in understanding the grammar of Lutsotso. Keywords: aspect, Bantu, Lutsotso verb How to Cite: Public Interest Statement Odera, H., & Barasa, D. -

Xxth-Century Theories of Language: an Epistemological Diagnosis

Pierre Swiggers CDU 801 11 19 11 Belgian National Science Foundation XXTH-CENTURY THEORIES OF LANGUAGE: AN EPISTEMOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS O. Introduction. This article is intended as a study in the methodology and epistemology of linguist ics, a field which developed out of theoretical linguistics in the past thirty years. Meth odology and epistemology (or philosophy)1 of linguistics can be subsumed under the general domain of 11 philosophical linguistics 11 (cfr. Kasher - Lappin 1977), which also includes a theory of meaning and reference, a theory of linguistic ( or, more generally semiotic) communication, and - in some cases - a formalization of linguistic subsys tems. The specific contribution of methodology and epistemology of linguistics lies in the definition of the object of linguistics, in the determination and justification of its re search techniques, in the appreciation of its results with respect to a broader field of in vestigation, in the reflection on the nature, status, and variability of approaches to lan guage. 2 The history of general linguistics (which is still an ill-defined concept) since the 11 11 11 11 beginning of this century shows that the basic notions - such as language , grammar , 11 11 11 11 (linguistic) meaning , (linguistic) structure - underwent a radical change in inten sion and extension, and have been focused upon from different points of view, in varie gated perspectives (cfr. Swiggers 1989). It would be presumptuous to analyse the vari ous 11 transformations of linguistics113 in this article; our aim here isto offer some ge- I am taking epistemology here in its "correlative" acceptation (viz. "epistemology of -"; cfr. -

Analyticity, Necessity and Belief Aspects of Two-Dimensional Semantics

!"# #$%"" &'( ( )#"% * +, %- ( * %. ( %/* %0 * ( +, %. % +, % %0 ( 1 2 % ( %/ %+ ( ( %/ ( %/ ( ( 1 ( ( ( % "# 344%%4 253333 #6#787 /0.' 9'# 86' 8" /0.' 9'# 86' (#"8'# Analyticity, Necessity and Belief Aspects of two-dimensional semantics Eric Johannesson c Eric Johannesson, Stockholm 2017 ISBN print 978-91-7649-776-0 ISBN PDF 978-91-7649-777-7 Printed by Universitetsservice US-AB, Stockholm 2017 Distributor: Department of Philosophy, Stockholm University Cover photo: the water at Petite Terre, Guadeloupe 2016 Contents Acknowledgments v 1 Introduction 1 2 Modal logic 7 2.1Introduction.......................... 7 2.2Basicmodallogic....................... 13 2.3Non-denotingterms..................... 21 2.4Chaptersummary...................... 23 3 Two-dimensionalism 25 3.1Introduction.......................... 25 3.2Basictemporallogic..................... 27 3.3 Adding the now operator.................. 29 3.4Addingtheactualityoperator................ 32 3.5 Descriptivism ......................... 34 3.6Theanalytic/syntheticdistinction............. 40 3.7 Descriptivist 2D-semantics .................. 42 3.8 Causal descriptivism ..................... 49 3.9Meta-semantictwo-dimensionalism............. 50 3.10Epistemictwo-dimensionalism................ 54 -

The Semantics of Progressive Aspect: a Thorough Study MOUSUME AKHTER FLORA & S.M

The Semantics of Progressive Aspect: A Thorough Study MOUSUME AKHTER FLORA & S.M. MOHIBUL HASAN Abstract In English grammar, verbs have two important characteristics--tense and aspect. Grammatically tense is marked in two ways: Present and Past. English verbs can have another property called aspect, applicable in both present and past forms of verbs. There are two major types of morphologically marked aspects in English verbs: progressive and perfective. While present and past tenses are morphologically marked by the forms verb+s/es (as in He plays) and verb+d/ed (as in He played) respectively, the morphological representations of progressive and perfective aspects in the tenses are verb+ing (He is/was playing) and verb+d/ed/n/en (He has/had played) respectively. This paper focuses only on one type of aspectual feature of verbs--present progressive. It analyses the use of present progressive in terms of semantics and explains its use in different contexts for durative conclusive and non-conclusive use, for its use in relation to time of reference, and for its use in some special cases. Then it considers the restrictions on the use of progressive aspect in both present and past tenses based on the nature of verbs and duration of time. 1. Introduction ‘Aspect’ has been widely discussed in English grammar with respect to the internal structure of actions, states and events as it revolves around the grammatical category of English verb groups and tenses. Depending on the interpretations of actions, states, and events as a feature of the verbs or as a matter of speaker’s viewpoint, two approaches are available for aspect: ‘Temporal’ and ‘Non-temporal’. -

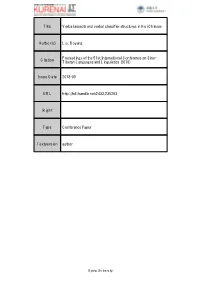

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

'The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language'

The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language UTSUMI Atsuko Meisei University, Tokyo Japan The Bantik language, which belongs to the Sangiric micro-group (cf. Sneddon 1993) within the Philippine group, has two morphologically indicated tense oppositions—the non-past tense and the past tense. In addition, the language includes progressive, habitual, and iterative aspects. This paper aims, first, to present an overview of the tense and aspect systems in the Bantik language. Although Philippine languages are normally described as not having tenses but, rather, as having aspect, a group of Bantik verbs seem to show a tense opposition. Second, it focuses on the classification of Bantik verbs with respect to the meanings they express by their tense forms. In short, stative verbs express a current event by using the non-past tense, while achievement verbs express a future event with the non-past tense. Activity verbs are categorized into two groups; the first group uses the non-past tense to express a current event, while the second group expresses a future event. Abilitative verbs, in contrast to the other verbs, use the non-past form to refer to a past event. 1. Overview of Bantik Morphology concerning tense and aspect 1.1 Overview of tense and aspect in Philippine type languages In much of the literature on the Philippine type languages which are found across the Philippines and from North to Central Sulawesi, verbs are described as having aspect, but not tense. Most of those languages are claimed to have moods as well. For example, Himmelmann (2005:363) shows that the Tagalog verb paradigm has both a perfective/imperfective aspect opposition and a non-realis/realis mood opposition. -

What Is the Problem of De Se Attitudes?∗

Penultimate draft. Forthcoming in About Oneself: De Se Attitudes and Communication, M. Garcia-Carpintero and S. Torre (eds.), Oxford University Press. What is the Problem of De Se Attitudes?∗ Dilip Ninan [email protected] 1 Introduction 1.1 Skepticism and exceptionalism It is widely thought that de se attitudes (aka indexical or self-locating atti- tudes) are special in some way, and that their distinctive features require some alteration to (once) standard philosophical views about propositional attitudes. This sort of claim was first made in contemporary philosophy in the 1960s and 1970s by, among others, Casta~neda,Perry, and Lewis.1 This work has proven influential, and the idea that de se attitudes pose a challenge to theories of attitudes is now the received view. But despite widespread agreement that there is a problem of de se attitudes (`the problem of the essential indexical' to use Perry's term), the literature on these topics has been less than completely clear on just what that problem is supposed to be. More specifically, what is unclear is what the distinctive problem of de se attitudes is, what problem such attitudes raise over and above other more familiar problems facing theories of propositional attitudes (e.g. Frege's Puzzle). Of course, one reason it might be difficult to unearth a distinctive problem in this vicinity is that, contra the received view, there simply is no distinctive problem of de se attitudes. This is the view of the de se skeptic, the philosopher who flouts the Perry-Lewis orthodoxy and holds that any problem raised by de se attitudes is really just instance of a more general problem. -

Events in Space

Events in Space Amy Rose Deal University of Massachusetts, Amherst 1. Introduction: space as a verbal category Many languages make use of verbal forms to express spatial relations and distinc- tions. Spatial notions are lexicalized into verb roots, as in come and go; they are expressed by derivational morphology such as Inese˜no Chumash maquti ‘hither and thither’ or Shasta ehee´ ‘downward’ (Mithun 1999: 140-141); and, I will argue, they are expressed by verbal inflectional morphology in Nez Perce. This verbal inflec- tion for space shows a number of parallels with inflection for tense, which it appears immediately below. Like tense, space markers in Nez Perce are a closed-class in- flectional category with a basic locative meaning; they differ in the axis along which their locative meaning is computed. The syntax and semantics of space inflection raises the question of just how tight the liaison is between verbal categories and temporal specification. I argue that in view of the presence of space inflection in languages like Nez Perce, tense marking is best captured as a device for narrowing the temporal coordinates of a spatiotemporally located sentence topic. 2. The grammar of space inflection There are two morphemes in the category of space inflection, cislocative (proximal) -m and translocative (distal) -ki. Space inflection is optional; verbs without space inflection can describe situations that take place anywhere in space.1 I will refer to the members of the space inflection category as space markers. Space inflection is a suffixal category in Nez Perce, and squarely a part of the “inflectional suffix complex” or tense-aspect-mood complex of suffixes.