Television and Young Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Articles Faculty Scholarship 1996 The Inevitable Wasteland: Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay 1997 Survey of Books Relating to the Law: Legal Regulation and Reform Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr. University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles Recommended Citation Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr., The Inevitable Wasteland: Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay 1997 Survey of Books Relating to the Law: Legal Regulation and Reform, 95 Mich. L. Rev. 2101 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. THE INEVITABLE WASTELAND: WHY THE PUBLIC TRUSTEE MODEL OF BROADCAST TELEVISION REGULATION MUST FAIL Ronald J. Krotoszynski, Jr.* ABANDONED IN THE WASTELAND: CHILDREN, TELEVISION, AND TBE FIRST A~mNDmEr. By Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay. New York: Hill & Wang. 1995. Pp. xi, 237. $11. More than thirty years ago, Newton N. Minow,1 then Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission ("Commission"), scolded broadcasters for failing to meet their obligations to the gen- eral public and, in particular, to the nation's children.2 Minow chal- lenged broadcasters to "sit down in front of your television set when your station goes on the air and stay there.. -

Important Dates for the 2009-2010 High School Admissions Process

IMPORTANT DATES FOR THE 2009-2010 HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS PROCESS Citywide High School Fair Saturday, October 3, 2009 Sunday, October 4, 2009 Borough High School Fairs Saturday, October 24, 2009 Sunday, October 25, 2009 Specialized High Schools Admissions Test Saturday, November 7, 2009 • All current 8th grade students Sunday, November 8, 2009 • 8th grade Sabbath observers Specialized High Schools Admissions Test Saturday, November 14, 2009 • All current 9th grade students • 8th and 9th grade students with special needs and approved 504 accommodations Specialized High Schools Admissions Test Sunday, November 22, 2009 • 9th grade Sabbath observers • Sabbath observers with special needs and approved 504 accommodations Specialized High Schools Make-up Test Sunday, November 22, 2009 • With permission only I MPORTANT WEBSITES and INFORMATION For the most current High School Admissions information and an online version of this Directory, visit the Department of Education website at www.nyc.gov/schools. The High School Admissions homepage is located at www.nyc.gov/schools/ChoicesEnrollment/High. To view a list of high schools in New York City, go to www.nyc.gov/schools/ChoicesEnrollment/High/Directory. You can search for specific schools online by borough, program, interest area, key word and much more! For further information and statistical data about a school, please refer to the Department of Education Annual School Report online at www.nyc.gov/schools/Accountability/SchoolReports. For further information about ELL and ESL services available in New York City public high schools, please visit the Office of English Language Learners homepage at www.nyc.gov/schools/Academics/ELL. For more information about Public School Athletic League (PSAL) sports, see their website at www.psal.org. -

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

Hasbro and Discovery Communications Announce Joint

Hasbro and Discovery Communications Announce Joint Venture to Create Television Network Dedicated to High-Quality Children's and Family Entertainment and Educational Content April 30, 2009 - Multi-Platform Initiative Planned to Premiere in Late 2010; TV Network to Reach Approximately 60 Million Nielsen Households in the U.S. Served by Discovery Kids Channel - - Joint Media Call with Hasbro CEO and Discovery CEO at 8:15 AM Eastern Today; Hasbro Investor Call with Hasbro CEO and Hasbro CFO & COO at 8:45 AM Eastern Today; See Dial-in and Webcast Details at End of Release - PAWTUCKET, R.I. and SILVER SPRING, Md., April 30 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Hasbro, Inc. (NYSE: HAS) and Discovery Communications (Nasdaq: DISCA, DISCB, DISCK) today announced an agreement to form a 50/50 joint venture, including a television network and website, dedicated to high-quality children's and family entertainment and educational programming built around some of the most well-known and beloved brands in the world. As part of the transaction, the joint venture also will receive a minority interest in the U.S. version of Hasbro.com. Both the network and the venture's online component will feature content from Hasbro's rich portfolio of entertainment and educational properties built over the past 90 years, including original programming for animation, game shows, and live-action series and specials. New programming will be based on brands such as ROMPER ROOM, TRIVIAL PURSUIT, SCRABBLE, CRANIUM, MY LITTLE PONY, G.I. JOE, GAME OF LIFE, TONKA and TRANSFORMERS, among many others. The TV network and online presence also will include content from Discovery's extensive library of award- winning children's educational programming, such as BINDI THE JUNGLE GIRL, ENDURANCE, TUTENSTEIN, HI-5, FLIGHT 29 DOWN and PEEP AND THE BIG WIDE WORLD, as well as programming from third-party producers. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

Press, Radio and Television in the Federal Republic of Germany

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 353 617 CS 508 041 AUTHOR Hellack, Georg TITLE Press, Radio and Television in the Federal Republic of Germany. Sonderdienst Special Topic SO 11-1992. INSTITUTION Inter Nationes, Bonn (West Germany). PUB DATE 92 NOTE 52p.; Translated by Brangwyn Jones. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Developing Nations; Foreign Countries; Freedom of Speech; *Mass Media; *Mass Media Effects; *Mass Media Role; Media Research; Professional Training; Technological Advancement IDENTIFIERS *Germany; Historical Background; Journalists; Market Analysis; Media Government Relationship; Media Ownership; Third World; *West Germany ABSTRACT Citing statistics that show that its citizens are well catered for by the mass media, this paper answers questions concerning the media landscape in the Federal Republic of Germany. The paper discusses: (1) Structure and framework conditions of the German media (a historical review of the mass media since 1945); (2) Press (including its particular reliance on local news and the creation of the world status media group, Bertelsmann AG);(3) News agencies and public relations work (which insure a "never-ending stream" of information);(4) Radio and Television (with emphasis on the Federal Republic's surprisingly large number of radio stations--public, commercial, and "guest");(5) New communication paths and media (especially communication and broadcasting satellites and cable in wideband-channel networks);(6) The profession of journalist (which still relies on on-the-job training rather than university degrees); and (7) Help for the media in the Third World (professional training in Germany of journalists and technical experts from underdeveloped countries appears to be the most appropriate way to promote Third World media). -

Lightning Strikes Sanibei Serving Pizza at by Jill Tyrer Quick-Thinking Bystanders Rushed to His Aid

AUGUST 12, 1999 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 32 28 PAGES f:-V -159GO€O1OG64O9*CAR~RT SORT R003 """ ' - U SANlBfct LIBRARY d • "(10 O^NLOP KD 33957 SANlHfcL Ft .JORTER GOSS TALKS TO KIWANIS East end home invasion suspect remains at large By Pattie Pace Staff Writer An unidentified man entered the Lindgren Boulevard home of Sanibei woman in her 80s last Saturday and, after tying her hands and feet with a plastic-coated wire and placing a towel over head, fled with approximately $5,000 in jewelry and cash. According to Commander John Terry, the woman was quickly able to free her hands and call police. Officers Jane Cechman and Dave Jalbert arrived on scene within minutes of the call and found the woman in the bedroom. She was bruised and cut from being tied up, but otherwise not physically harmed, according to Terry. The burglar used a stick to poke the woman, but was other- wise unarmed. The officers searched her home and canvassed the neighborhood but could not find the intruder, described as a white male, approximately 40 years old, 5 feel 10 inches tall with a slender build and scraggly, blond chin-length hair. He wore a long-sleeve shirt with faint multicolored thin stripes, long pants, dirty brown work shoes with thick soles and loose untied laces, according to a police press release. » — * • Michael 1'iotdlu Police are asking anyone .who saw a man matching that U.S. Representative Porter Goss listens to a question at the Saiiibel/Captiva.Kiw:a*jiis, CJwb, •""'ctescrlptidn or i suspicion car-in the area of-Lindgren weekly breakfast at the Island House where he was the speaker. -

YEAR in REVIEW Australian Music Industry Based on a Strong the YEAR in REVIEW – Vision to Become a Globally Recognised Music Nation Powerhouse

YEAR IN REVIEW Australian music industry based on a strong THE YEAR IN REVIEW – vision to become a globally recognised music nation powerhouse. MESSAGE FROM CHIEF Financial Overview A record year for APRA AMCOS with group EXECUTIVE DEAN ORMSTON revenue breaking the $400m milestone, Brett Cottle AM retired as CEO in June 2018 after 28 rising by 8.7% from $386.7m to $420.2m, an years presiding over a period of extraordinary increase of $33.5m on the back of continued change and growth for the organisation. Over strong growth in consumer demand for music the past 6 months there have been many delivered digitally. ‘farewell’ events and acknowledgements For APRA, gross collections rose by 10.4% to of Brett’s contribution to APRA AMCOS, $323.3m (excluding AMCOS management the wider rights management and fees), while AMCOS revenue rose 3.3% to music industries, both locally and $95.9m. internationally. I would like to add my Operating expenses across the group – personal further thanks to Brett for comprising APRA pro forma costs, system being a leader unparalleled, and a development related costs, costs of generous mentor. administering AMCOS and stand-alone This year’s report highlights the AMCOS costs – were $57.1m, up 13.1% strength of the organisation’s from last year’s figure of $50.5m. economic performance, breadth of Despite the increased system member service, and commitment to development spend APRA Net improving our industry’s ecosystem. Distributable Revenue – the amount Critical to the health of our sector is available for distribution to a direct conversation and relationship members and affiliated societies – with Federal and State governments. -

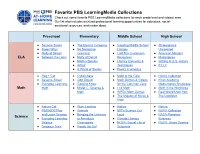

Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections Check out Some Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections for Each Grade Level and Subject Area

Favorite PBS LearningMedia Collections Check out some favorite PBS LearningMedia collections for each grade level and subject area. Our list also includes archived professional learning opportunities for educators, social- emotional resources, and maker ideas. Preschool Elementary Middle School High School ● Sesame Street ● The Electric Company ● Inspiring Middle School ● Shakespeare ● Super Why! ● No Nonsense Literacy Uncovered ● Molly of Denali Grammar ● LGBTQ+ Curriculum ● American Masters ELA ● Between the Lions ● Molly of Denali Resources ● Masterpiece ● Martha Speaks ● Literary Elements & ● Writing in U.S. History ● Arthur Techniques ● It’s Lit ● A World of Stories ● Poetry in America ● Peg + Cat ● Cyberchase ● Math at the Core ● NOVA Collection ● Sesame Street ● Odd Squad ● Math Games & Videos ● Khan Academy ● Everyday Learning: ● Good to Know for the Common Core Mathematics Showcase Math Math ● Mister C: Science & ● I <3 Math ● Math in the Workforce Math ● WPSU Math Games ● Real World Math from ● The Majesty of Music & The Lowdown Math ● Nature Cat ● Plum Landing ● Nature ● Nature ● PBS KIDS Play ● Animals ● MIT's Science Out ● NOVA Collection and Learn Science ● Bringing the Universe Loud ● NASA Planetary Science ● Everyday Learning: to America’s ● Climate Literacy Sciences Science Classrooms ● NOVA: Secret Life of ● NOVA: Gross Science ● Dinosaur Train ● Ready Jet Go! Scientists ● Let’s Go Luna ● All About the Holidays ● Teaching with Primary ● Access World Religions ● Xavier Riddle and ● NY State & Local Source Inquiry Kits -

Housing for the Elderly

Thursday, December 29, 1977 Nytsa Gatt City Journal • Nyssa, Oregon Page Eleven ÉBM Insulation Manufacturing Business Location In Parma ••••••••eooeoeooooeoeeeoeeooeooooee ••••••••••••••a• •••• aaaabsaaa TV SCHEDULE The Jon Ball family have tested by the U.S. Testing Deadline Wednesday 11 a.m., Phone 372-2233 wholesale prices to contrac started a new business in Company, Inc., in Los An tors and insulators or they Parma that manufactures geles and found to be light will do blow-in jobs them low-cost, high-quality cellu I weight, non-toxic, non-cor selves. 7:9 Wacke lose insulation by chemically rosive, safe to handle, vermin 8 00 Herald of Troth SAS Disposal The Ball family has lived in 8 >0 Day of Discovery I treating recycleable waste resistant and a flame re OO Oral Roberta Parma for over three years. W It la Written "Our Business is CLEARANCE SALE products. tardant. It passes flame re 10t 00 Dwayne Friend I They have seven children of Cellulose insulation is ma tardant tests comparable to: 10 Kt NFL Championship Game Picking Up!" their own that attend the 5:00 Question of the Week I 25% off any men's or women’s Jeans nufactured from old news UL4723, NFPAF255, UBC# 5 30 Face the Nation local schools. They have 6.00 Sixty Minutes 20% off all children’s clothes paper and has one of the 42-1, ANSI 4A2-5 and ASTM been foster parents for three 7 00 Rhoda • 30 to 50% off all Jackets, men’s, women’s A kids highest values of all types of 4E-84.